Farmer Burns

James “Farmer” “Slab” Burns, “the Ashtabula Midget,” had two more nicknames than innings pitched in Major League Baseball. Standing 5-foot-7 and weighing 168 pounds, it’s easy to assume how he earned one of those, but the origin of the other two monikers is not the only mystery presented by James Burns.1 As of 2017, no one knows the date of death, or the final resting place of the 1901 St. Louis Cardinals pitcher. Part of the difficulty is due to incongruences associated with the ballplayer’s place of birth, birthday, and the commonness of his name.

James “Farmer” “Slab” Burns, “the Ashtabula Midget,” had two more nicknames than innings pitched in Major League Baseball. Standing 5-foot-7 and weighing 168 pounds, it’s easy to assume how he earned one of those, but the origin of the other two monikers is not the only mystery presented by James Burns.1 As of 2017, no one knows the date of death, or the final resting place of the 1901 St. Louis Cardinals pitcher. Part of the difficulty is due to incongruences associated with the ballplayer’s place of birth, birthday, and the commonness of his name.

When Burns mopped up the ninth inning for the Cardinals on July 6, 1901, his moment on the mound included hitting a batsman hard enough to knock him out of the game.2 In the bottom of the ninth, Burns led off with a walk, stole second, and scored on a base hit. The Cardinals proceeded to bat around, and when Burns’s spot in the order came back up, he was lifted for a pinch-hitter and never made it back into a big-league ball game.3 As of 2017, Burns was one of only 10 men to have more stolen bases than at-bats.

James Burns’s career statistics are listed in baseball encyclopedias and online databases under the name Farmer Burns, with the additional nickname “Slab.”4 Farmer Burns’s birthplace is listed as Ashtabula, Ohio, with a birthdate of June 2, 1876. In a 1945 write-up in a Steubenville, Ohio, newspaper of Slab Burns’s playing days, with the one-time big league pitcher in failing health at age 69, Burns’s place of birth was provided as England.5 Slab’s name was printed as James Joseph Burns, born June 6, 1876 to Irish parents, Peter and Catherine (Condron) Burns. Ancestry.com has a Social Security application dated August of 1938 by a James Slab Burns with a date of birth of June 2, 1876 with matching parents to the 1945 article, but states his place of birth as Brady’s Bend, Pennsylvania.6 No census records could assist in definitively confirming any of these discrepancies.

Whenever and wherever he was born, Slab Burns was described in 1945 as “a scintillating star of the baseball diamond, the football field, and the basketball floors. He was stocky built, a bundle of muscle, cool, courageous in his playing, quiet, unassuming, never got rattled or punched anybody in a game […] an all around athlete, quick on his feet, despite his bulk.”7

Slab Burns’s athletic pursuits saw him first suit up with the Y.M.C.I basketball team in Steubenville, and the Steubenville Acme Glass Works football and baseball teams. On the first play from scrimmage with Acme in November of 1896, “Slab Burns, the fullback on the Acme team, was badly injured […] having his collar bone broken and breast crushed.”8 It was also reported that Slab played fullback at Washington and Jefferson College. The same news story has him at Pittsburgh College of the Holy Ghost in 1897, where he played tackle in addition to pitching duties.9 No records could be found of a James Burns attending either institution. 1899 saw Slab on the gridiron and ball diamonds for East Liverpool, Ohio.10 The Steubenville Herald Star reported in 1900 that “Slab Burns, the well known ball player, has signed with Toledo and has closed his saloon in this city to join the club.”11 Baseball-reference.com has Farmer Burns appearing in 3 games with Toledo, as well as 5 games with Grand Rapids, but the games in Michigan do not match the newspaper narrative.

After his signing with the Cardinals, a Steubenville paper stated that “Jas. ‘Slab’ Burns of this city left Sunday to join the St. Louis National League base ball team. Burns has been pitching for Ashtabula and his speedy work with all kinds of curves attracted the attention of the St. Louis club, so it engaged his services. Burns has pitched for the Acme ball team of this city, for Pittsburg College team and played football with both teams; also pitched for Toledo, Tecumseh, Coldwater, Michigan, and for Schenectady, NY. He is a good, safe batter.”12

The St. Louis papers relayed that the righty pitcher represented his potential home town of Ashtabula for two seasons in the Ohio State leagues before joining St. Louis. It was upon recommendation of Cardinals second basemen, Dick ‘Brains’ Padden that Burns signed on June 30, 1901. Two days later he was practicing at St. Louis’s Robison Field.13

The St. Louis Republic quickly dubbed him “a phenom,”14 and in another article backed it up, “James Burns is said to be anything but a false alarm by those of his teammates who have worked out in front of him. They claim that he has speed, curve, control and change of pace which will make him a winner.”15 The Sporting Life declared Burns “the duplicate of [Bill] Keister […] in general build,” and that he “has speed and curves galore.”16

Before he had thrown his first pitch, the Republic heaped on more praise:

“Burns has the appearance of a young Irishman who will be hard to beat in any company. He was at League Park17 yesterday and took a work out with the amateurs, who are always willing to bat at the benders of a professional. Burns is of stout build, somewhat on the lines of “Red” Donahue,18 and, strange to say, he has a tinge of auburn running through his hair which, in him, signifies faster balls and more puzzling curves with each bingle made by his opponents. Burns says that he has not lost a game in the last two years in his Ohio home. He realizes that he has been called upon to win in fast company, but with that pluck which makes great men in any line he says he will do his best and thinks that will be plenty good enough to keep him on the roster of the St. Louis club for several years to come. If looks count for anything, Burns will win his share of the games in which he officiates.”19

Burns made his debut a week after signing, in a Saturday game at the beginning of the Cardinals’ longest homestand of the season. Ten thousand fans saw a lopsided drubbing of the home team by Philadelphia, who scored in every inning but the first.20 With Philadelphia leading 13-2, Burns, the fourth pitcher of the day used by manager Patsy Donovan, trotted in to face the meat of the Phillies lineup. Working with batterymate Jack Ryan squatting in front of umpire Hank O’Day, Burns faced seven batters, walked one, hit another, and gave up a triple and a single, all of which scored only one run. The ever-admiring St. Louis Republic wrote:

“Jimmy Burns, the Ashtabula midget, managed to last through the ninth inning. [Roy] Thomas was passed on balls; [Bill] Hallman flew out to [Emmet] Heidrick; [Ed] Delahanty singled and was caught trying to stretch the hit into a double; Elmer Flick tripled to left, scoring Thomas. [Harry] Wolverton was hit by a pitched ball. There was so much speed to the shoot that the Quaker third-sacker was forced to retire from the game, [Shad] Barry taking his place. [Hughie] Jennings was retired on a pop fly to [Bobby] Wallace.”21

Ten days later it was payday for the Cardinals and “Jimmy Burns stood around the office as if he expected to hear something about a 10 days’ notice. … But he has no need to worry, he has not been released.”22 But the next day the Republic announced that Burns had been “farmed out to the Grand Rapids club of Michigan.”23

Burns’s first start in the Western Association came on July 17. “Burns, a new man on the Grand Rapids team, was easy picking for Toledo today, while [Addie] Joss was in good form and had fine support,” an Indianapolis paper mentioned.24 It was one of Joss’s 25 wins for Toledo that season. Burns never did get the best of Joss, losing three straight matchups with the Hall of Famer, but he did pitch a no-hitter on August 25 against Matthews.25 The performance was called both remarkable and brilliant. “For nine innings the squatty youngster let the Matthews aggregation down without the semblance of a hit or run.”26

Readily available records indicate that Burns went 12-7 for manager Walt Wilmot, including striking out a season-high nine Fort Wayne batters in eight scoreless innings in the heat of the pennant race.27

Grand Rapids needed both games of a doubleheader against Marion on the last day of the season to finish atop the Western Association standings. Burns took the mound in the opening game before 3,500 fans, winning 18-8. Grand Rapids cruised to a 7-1 victory in game two, which was called on account of darkness in the seventh inning.28 A month later, Western Association owners disallowed two of Grand Rapids’ victories; one due to the Wheeling team being delayed by a wreck, and another which turned out to be an unscheduled match with Matthews. The pennant was instead awarded to second-place Dayton.29

Slab was back with the Acme footballers in the fall of 1901, and scored a touchdown that accompanied almost every retelling of his playing days. The play involved a tripped but untouched Burns being carried by the arms and legs for 50 yards by Tom Needham and William “Gicks” Houser across the goal line against a rival squad from Pittsburgh.30

Further sketches of Slab’s playing days describe him making a stop in the Eastern League with Jersey City in 1902. There is a Burns pitching in three games in mid-June for the Skeeters, but no first name was verifiable.31 “Burns, an athlete of rare ability,” was back in the Steubenville paper at the tail end of the 1902 season, a sports scribe relaying he had been with Fort Wayne and had finished the season with Wheeling.32 Again, no records were available to elaborate on his time in either Indiana or West Virginia.

A year later the Record-Argus (Greenville, Pennsylvania), told of the 27 year-old pitching for South Sharon, Pennsylvania, “Woozy old Slab Burns, whom the St. Louis Nationals were foolish enough to try a couple years ago,” failed to last two innings. “The heavy man of the show […] was out of condition.”33 With his skill set seeming to deteriorate, Burns started to mix in a pitch he called “a floater.” Described in 1945 as “a balloon pitch,” he gripped the ball between his pinky and thumb and delivered what modern sportswriters would describe as similar to the eephus popularized by Rip Sewell.34

In 1903, pre-season chatter within the pages of the Pittsburgh Gazette stated that “Slab Burns of Wheeling,” may sign with Homestead, Pennsylvania.35 By July 20, Homestead manager Howard Risher had released Burns “for showing lack of control.”36 James Burns appears to be missing from the 1904-05 seasons, but there is a Burns catching for East Liverpool (Ohio) in the Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Maryland (P.O.M.) League in 1906.37 Burns then drops off the baseball map for good.

The only other clue comes from a World War I draft registration dated September 1918 for a James Joseph Burns who was tall, of medium build, with blue eyes, and black hair, and born outside the United States on June 2, 1876. His occupation was listed as a millwright at the La Belle Iron Works of Steubenville. James’s closest living relative was his mother, Catherine Burns, living in Houston, Pennsylvania. This James Joseph Burn’s permanent home address, 807 Highland Avenue in Steubenville, matches the general vicinity given as Slab’s “shack abode […] on North Eighth west side rear north of Franklin” from the 1945 newspaper.38

The inconsistencies in the details of James Burns’s life could be chalked up as simple data entry errors, the guesswork of reporters, or the responses of a man who didn’t know much about his childhood. The Farmer nickname seems to have been the work of St. Louis newspapermen, and may have been an attempt to tout the youngster in connection with the world champion catch-as-catch-can wrestler Martin “Farmer” Burns, who was famous throughout the Midwest around the turn of the century.39 If Slab was not the given middle name of the James Burns who applied for Social Security benefits in 1938, then it is a nickname more befitting a tall, husky, bulky, heavy, dark-headed footballer than that of a “midget” red-headed, Irish pitcher.

But this author is not the only researcher to scratch his head while inquiring after Burns. A player of special interest to SABR co-founder Bill Haber, James Burns was the Mystery of the Month in the September 1997 Biographical Research Committee Monthly Report. Burns’s date of death and final resting place remain an elusive mystery, or as Bill Carle put it in that report, “Where is Slab’s Slab?”40

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to fellow SABR members Mark D. Aubrey, Craig Brown, Skylar Browning, Bill Carle, Jacob Pomrenke, and Chris Rainey for their assistance in helping me stay on the Burns beat. While the disparities in Burns’s story mounted, the author was supported by their research on more than one occasion. Without their cooperation this piece would have more holes in it than remain after their assistance.

A special tipping of the cap is due to Warren Corbett for his support of this bio.

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen and Warren Corbett.

Sources

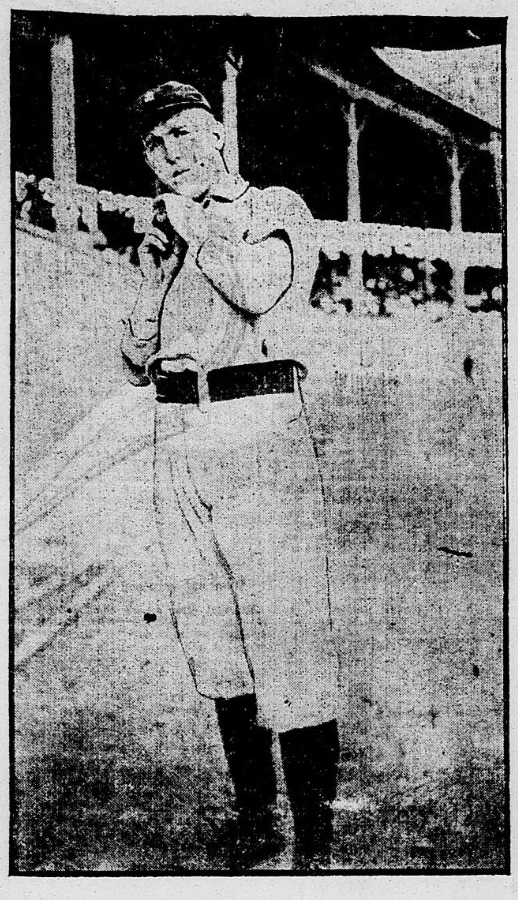

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on online newspaper archives including The Sporting News and Sporting Life, as well as the Chronicling America newspapers, the Grand Rapids Press available through genealogybank.com, as well as the newspapers.com resource. Additional information was verified in the player’s file at the Hall of Fame Museum and Library in Cooperstown, New York. A good deal of information was dealt the author’s way by Erika Grubbs, Genealogy Librarian at Schiappa Library in Steubenville. Acquiring census data from familysearch.org proved fruitless, while pieces of the tattered tale were retrieved from Ancestry.com. Additional phone calls and emails to libraries, museums, cemeteries, the Social Security administration, and the IRS were all for naught. The photo comes from the St. Louis Republic on July 11, 1901.

Notes

1 “New Twirlers,” Sporting Life, July 13, 1901.

2 According to Lee Sinins’s Complete Baseball Encyclopedia, through 2016 there have been at least 112 pitchers 5’7” or shorter. Sinins’s book has Lee Viau, Dinty Gearin, and Deacon Morrissey, listed at 5’4”, being the game’s shortest. Baseball-Reference tabulates 170 such hurlers, and has three shorter than Sinin’s list: Cub Stricker, Larry Corcoran, and Dickey Pearce being listed at 5’3”!

3 Pete Childs pinch hit for Burns and “failed entirely.” Ten days later Childs was released by St. Louis and picked up by the Cubs.

4 “New Twirlers,” Sporting Life, July 13, 1901. This article appears to be the origin of the nickname Farmer, but not its only usage, as the Farmer nickname appeared both the St. Louis Globe Democrat and St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

5 Chalmers C. White, “‘Slab’ Burns Now Forgotten ‘Hero’,” Steubenville Herald Star, June 22, 1945 – quoted almost in its entirety in the SABR Biographical Research Committee Monthly Report, September 1997

6 Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

7 White, “‘Slab’ Burns Now Forgotten ‘Hero.’”

8 Pittsburgh Press, November 15, 1896

9 White, “‘Slab’ Burns Now Forgotten ‘Hero’”; “Slab Burns as a Member of W. & J. Foot Ball Team Calls Forth a Protest,” Steubenville Herald Star, October 13, 1902. Holy Ghost eventually became Duquesne University.

10 Evening Review (East Liverpool, OH), October 14, 1899; Evening Review (East Liverpool, OH), September 9, 1899.

11 Steubenville Herald Star, May 24, 1900.

12 From the notes of Bill Haber, “Ashtabula, Ohio, July 1, 1901, with a subheading of Steubenville, Ohio,” courtesy of the SABR Biographical Research Committee Chair, Bill Carle; Additionally, there is a Burns who pitched in 9 games for Schenectady (New York State League) in 1899 listed with Baseball-Reference, as well as 3 games the same season with Auburn/Troy.

13 “Triumphant Trip of Donovanites,’ St. Louis Republic, July 3, 1901.

14 “New Twirlers May Force Out a Player,” St. Louis Republic, July 1, 1901.

15 St. Louis Republic, July 5, 1901.

16 “New Twirlers,” Sporting Life, July 13, 1901.

17 Not the famed home of the Cleveland Blues, but another name for Robison Field in St. Louis.

18 Donahue is a curious comparison, as Francis L. stood 6 feet tall and weighed 187 lbs.

19 “Triumphant Trip of Donovanites,” St. Louis Republic, July 3, 1901.

20 “Quakers Held a Slugging Carnival,” St. Louis Republic, July 7, 1901.

21 “Burns Made Good Impression,” St. Louis Republic, July 7, 1901.

22 St. Louis Republic, July 16, 1901.

23 Ibid., July 17, 1901.

24 “Burns Easy for Toledo,” Indianapolis Journal, July 18, 1901.

25 “Allows No Hits,” Topeka State Journal, August 29, 1901.

26 “Didn’t Get A Hit, Remarkable Pitching Feat By Placid Mr. Burn,” Grand Rapids Press, August 26, 1901:4.

27 “Burns Struck Out Nine Men,” Indianapolis Journal, August 11, 1901; “Fort Wayne Used the Bat Well,” Indianapolis Journal, July 24, 1901; “All Looked Alike to Grand Rapids,” Indianapolis Journal, July 31, 1901; “Divided the Honors,” Indianapolis Journal, July 28, 1901; Marietta Daily Leader, July 31, 1901; “Burns an Easy Proposition,” Indianapolis Journal, August 6, 1901; “Infield Errors Were Costly,” Indianapolis Journal, August 15, 1901; “Burns Easy for Toledo,” Indianapolis Journal, August 17, 1901; “Grand Rapids Batted Hard in the Fifth and Won the Game,” Indianapolis Journal, August 21, 1901; “Easy Victory for Matthews,” Indianapolis Journal, August 24, 1901; Indianapolis Journal, September 9, 1901.

28 “Grand Rapids Takes Two,” Indianapolis Journal, September 23, 1901.

29 “They Just Juggled Two of Three Games,” Grand Rapids Press, October 10, 1901:3; “Embezzlement Charged Against President Meyer,” Mansfield (Ohio) News, October 10, 1901:3.

30 Chalmers C. Chalmers, “Recalling First Football Contest Played in Steubenville 50 Years Ago,” Steubenville Herald Star, November 8, 1943; “From Old Files,” Steubenville Herald Star, November 21, 1941.

31 Waterbury Democrat, June 12, 1902; New York Tribune, June 13, 1902; New York Tribune, June 18, 1902; Waterbury Democrat, June 18, 1902; New York Tribune, June 21, 1902; Waterbury Democrat, June 21, 1902. The Jersey City manager, Thomas E. Burns died in his sleep of heart disease days before the season started in the home of league president, Patrick Powers.

32 “Slab Burns as a Member of W. & J. Foot Ball Team Calls Forth a Protest,” Steubenville Herald Star, October 13, 1902.

33 Record-Argus (Greenville, PA), September 25, 1903.

34 Chalmers C. White, “‘Slab’ Burns Now Forgotten Hero,” Steubenville Herald Star, June 22, 1945.

35 Pittsburgh Gazette, April 1, 1903

36 Ibid., July 20, 1903

37 “P.O.M. League Season Opened In This City,” Steubenville Herald Star, May 31, 1906.

38 White, “‘Slab’ Burns Now Forgotten ‘Hero.’”

39 Farmer Burns was a world champion wrestler who trained James J. Jeffries in 1910.

40 SABR Biographical Research Committee Monthly Report, September 1997; http://sabr.org/cmsFiles/Files/Biographical%20Research%20NL%20Sept%201997.pdf.

Full Name

James Joseph Burns

Born

June 2, 1876 at Ashtabula, OH (USA)

Died

, ---- at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.