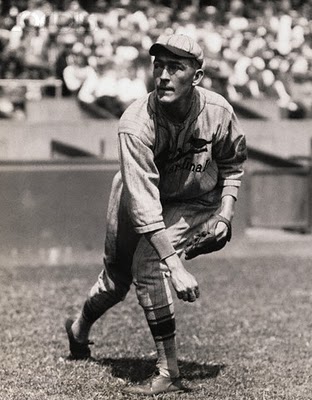

Flint Rhem

Pitcher Charles Flint “Shad” Rhem is part of a notorious baseball species. While he put together 12 seasons in the majors, and had a 20-win season in 1926, most of the stories told about him revolve around alcohol. Some sportswriters, like Bob Broeg, go so far as to say that Rhem “boozed away the greatness expected of him.”1

Pitcher Charles Flint “Shad” Rhem is part of a notorious baseball species. While he put together 12 seasons in the majors, and had a 20-win season in 1926, most of the stories told about him revolve around alcohol. Some sportswriters, like Bob Broeg, go so far as to say that Rhem “boozed away the greatness expected of him.”1

Whatever the case, the various legends certainly make for fascinating reading. Broeg remembered a time when manager Gabby Street scolded Rhem for drinking, and Flint replied, “Well, Sawge, ah was with Alex, and ah figured he was mo’ potent to the club than me, so ah drunk the fastest and the mostest.”2 Alex was probably Grover Cleveland Alexander, a fellow pitcher with the St. Louis Cardinals and Rhem’s drinking companion. Apparently on another occasion, Rhem fell asleep in the bullpen after a long night of drinking, and woke up with adhesive tape over his eyes, making him think he’d gone blind.3 During one game, perhaps not prompted by drink, he asked the groundskeeper for a trowel and stopped the game to do some landscaping on the pitching mound. There were many other such stories, including the famous “kidnapping,” which we’ll get to a little later.

Rhem had three separate stints with the Cardinals, being traded three times and bought back twice. He pitched in five games for the 1934 team before being traded away in June.

Charles Flint Rhem was born in Rhems, South Carolina, not far from the coastal town of Georgetown, on January 24, 1901. Rhems, an unincorporated area near Black Mingo Creek, was named for the Rhem family after Flint’s ancestor, Furnifold Rhem, Sr., settled there in 1846. Flint was one of nine children born to Durward Dudley Rhem and his second wife, Margaret Esther (Essie) Durant, whom he married in 1893. In 1900 the Rhems were living in Mingo, Williamsburg County, South Carolina. Living with them were daughter Lauria, the child of Durward’s first marriage, and Laura, Durward, Durant, and Furnifold, offspring of the second marriage.

Flint was named after New York shipbuilder Charles Flint, who was a lifelong friend of his father’s. Durward Rhem worked in the family business, F. Rhem & Sons, which was extensive and included the production and sale of cotton, naval stores, turpentine, real estate, timber, land, shingles, and the Black River and Mingo Steamboat Company. Durward died in July of 1922 of complications from diabetes.

Rhem studied engineering at Clemson University from 1920 to 1924, but apparently did not graduate. According to The Cardinals Encyclopedia, Flint was bashful and gawky when he arrived at Clemson. Although he had been playing baseball since he was 9 years old, he did not intend to play in college. Indeed, he said later that his father disapproved of the sport, thinking it too rough-and-tumble. Flint said later, “I’d have to sneak off and play baseball when I was a kid. … My parents thought only cutthroats and roughnecks played baseball. Maybe they were right.”4 Someone brought him to the attention of the coach, however, and he played from 1922 to 1924, averaging 15 strikeouts per game. His nickname while at Clemson was not Shad, but Big Smoky. In an undated clipping provided by East Carolina University, Rhem is called “the leading college pitcher of South Carolina. … [He] is a wonderful strikeout pitcher, probably the leader of the South in this respect.”

Along the way Rhem also played for some teams in the South Carolina textile leagues. In 1922 he played for Westminster of the Oconee County League, and the following season he played for Belton of the Saluda Textile League, a team that also included future major leaguer Leroy Mahaffey. W.A. (Willie) Hawkins, a former player with the Oconee Mills Mountaineers, remembered that Flint could hold five baseballs in one hand, and called him the “most talented baseball player and athlete I can recall seeing play the game.”5

In 1922 Flint actually tried to bring himself to the attention of Frank Navin, owner of the Detroit Tigers. His letter to Navin came to the attention of player-manager Ty Cobb. In his autobiography, Cobb called this “one more on a long list of my bitter memories. In 1922 I received a letter from Rhem. … His spelling didn’t indicate that he was about to graduate magna cum laude, but young Flint cited a flock of one- and two-hitters he’d pitched and asked for a tryout in Detroit.”6 In May 1923 Cobb wrote back to Rhem, and his reply is preserved in the collection of East Carolina University. He encouraged Flint to join the Tigers, saying that the team sported a number of Southern boys, many of them college-educated. He went on to say, “If you have the ability, you can expect the Detroit Baseball Club, through myself and Mr. Navin, the owner, to look out for your best interests. … Now, if you haven’t the goods, then you do not want to be in baseball, but if you have, then when you have shown your ability, I can absolutely assure you that Mr. Navin will pay you as much or more in salary than any other man in baseball. I say this as a ball player, a Southern boy, and one who is interested in a man from my section of the country. We would like to have you with us.”7

Cobb’s assurances proved to be hollow, however. Frank Navin was not interested, and according to Cobb, Rhem “turned out to be a regular Frank Merriwell at the college level” and then turned into a real star for St. Louis several years later. Flint actually signed with the Cardinals in 1924 and joined them for spring training. In a letter to his mother, he mentioned that his arm had been bothering him since his arrival in camp, and that he had “asked Mr. Branch Rickey to send me out to a small League for two or three months so I could get some more experience. He said he thought it was best too for me.”8

Rhem was assigned to the Fort Smith (Arkansas) Twins of the Class C Western Association on April 16. He had a 22-15 record with Fort Smith that year, leading the league with 282 strikeouts. On August 21 he pitched a no-hitter against the Hutchinson Wheat Shockers, and Rickey brought him back up to the big leagues, where he debuted with the Cardinals on September 6. He pitched six games for the Cardinals that year, finishing with a record of 2-2 and an earned-run average of 4.45. The nickname Smokey followed him from Clemson to St. Louis, where he was listed that way on the Cardinals’ roster. It was apparently only later that he received the nickname Shad because of all the fish stories he told.

After the 1924 season ended, Rhem managed to make yet another appearance with a textile mill team, this time on October 11 with Brandon Mill. Brandon was playing Judson for the league championship, and both teams had brought in players to beef up their ranks. Judson had recruited infielder Walt Barbare, who had last played for the Pirates. Brandon had Rhem and future major leaguer Pel Ballenger. Brandon came away with the championship.

By May 1925 the Atlanta Constitution was predicting great things for Rhem. Observing that he took the engineering course at Clemson “with fair success” and “the baseball course with wonderful results,” the paper noted that he had averaged 16 strikeouts per game at Clemson while allowing only one to three hits in most of his games. On a more personal level, the Constitution portrayed Flint as “a southerner through and through … a tall, husky, supple boy, earnest, [with] a lot of unction, a pronounced southern drawl and a lot of courage, confidence and good sense.” According to the Constitution, Rhem had kept a tabulation of his strikeouts with Fort Smith and maintained that he had over 300, the difference coming because his records on the road were not kept carefully. As for his playing style, “Rhem has a rifle shot fast ball, sharp curves … an old fashioned ‘drop,’ and he has the physique and the natural turn to make a great pitcher. Rickey regards him as the most wonderful prospect of recent years if he will only concentrate his entire effort and thought on the game.”9

Rhem remained with the Cardinals through the 1928 season, compiling a record of 49-40. In 1925 he appeared in 30 games, 24 of which he started. He pitched 170 innings, and had a record of 8-13 and an ERA of 4.92. On May 9, in a game against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds, he struck out ten batters while hurling a complete-game shutout

The 1926 season was the best of Rhem’s career. He and three other pitchers tied for the NL lead in wins, with 20. He started all of the 34 games he appeared in, and pitched 20 complete games. From May 6 to July 1, he had an eight-game winning streak. In a career-high 258 innings Rhem had an ERA of 3.21. The Cardinals were in a close race with the Cincinnati Reds, and on September 16 Rhem pitched in the first game of a doubleheader with the Philadelphia Phillies, leading the Cardinals to a 23-3 win. Thirty-six players were used in the course of the marathon game, 22 by the Phillies.

The Cardinals won both the pennant and the World Series that year. This was the first pennant for St. Louis in 38 years. Flint started Game Four of the Series against the Yankees, but was removed in the bottom of the fourth for a pinch-hitter after giving up two home runs to Babe Ruth. Rhem was part of baseball history, however, since this was the game in which Ruth fulfilled his promise to a bedridden boy, Johnny Sylvester, by hitting three home runs. While Rhem tied for the league lead with his 20 wins, and was third with a won-lost percentage of .741, he was also third in the league in the number of hits given up per nine innings pitched, 8.407.

The next year did not produce a stellar season for Rhem. He refused to sign his contract at first, and missed spring training. In an interesting telegram from Branch Rickey to Flint dated April 2, 1927, Rickey said, “Mr. Breadon’s [Cardinals owner Sam Breadon] position on salary unchanged and terms in his last wire to you are definite and final. However I think you and I can make some adjustment on basis of conditional clause in contract previously referred to in our correspondence.” This conditional clause was apparently that Rhem would receive a total of $2,500 in bonus money if he refrained from drinking during the season.

Although he had pitched two two-hitters and one three-hitter by early June, Rhem’s frequent drinking was beginning to cause problems. In July Breadon fined him $2,000 for violating training rules. This fine was the remainder of his $2,500 conditional bonus, of which $500 had already been paid for good behavior. Flint actually threatened to quit baseball because of the incident, but was back with the team within a few days.

Rhem was a holdout again in 1928, but rejoined the Cardinals after they threatened to trade him. That year his record was 11-8, and the Cardinals won another pennant. In May Jesse Haines wrote in Baseball Magazine that “Flint Rhem has a knuckle ball that would make your hair stand on end. But catchers don’t like to have him use it for neither they, nor he, nor anyone else knows just where it’s going when he cuts loose with it.”10 According to The Cardinals Encyclopedia, manager Bill McKechnie wanted Rhem to start the third game of the 1928 World Series against the Yankees, but his mother didn’t want him to pitch on a Sunday. He ended up pitching two innings in relief, anyway.

By December of 1928, Rhem had been banished to the Minneapolis Millers of the Double-A American Association. Manager McKechnie, quoted by the Associated Press in the Milwaukee Journal on December 16, said “Rhem did not fit into our club. … He thought more about doing as he pleased than he did about helping out the club. Furthermore, in his infractions of club rules he took others with him. … (T)he fact that the other major league clubs passed him along indicates that Rhem has been pretty well sized up by the managers of both leagues.”11 Rhem appeared in 23 games for the Millers that year, compiling a 5-11 record. Later in the season he played for the Houston Buffaloes of the Class A Texas League, where he went 7-2.

On April 10, 1930, Flint married schoolteacher Lula Dillard, a graduate of Anderson College in Indiana. Gabby Street, the new manager of the Cardinals, decided to give Rhem a second chance. The St. Louis correspondent of The Sporting News, quoted in an unidentified newspaper called the Sunday Record, said, “Rhem has been a wayward boy and for this reason he was removed from major league environs last season and sent to Minneapolis. He did not stay the season, however, but moved on to the Cardinals’ farm at Houston. He pitched some mighty good ball there, but got into difficulty toward the close of the season and found himself suspended. Reinstated over the Winter, he was placed on the Cardinal reserve list and Skipper Street believes he can help him. At least he wants to try and if he succeeds, the Cardinal pitching staff will have a big asset.”12 Rhem posted a 12-8 record and a 4.45 ERA with the pennant-winning Cardinals that year. St. Louis lost the World Series to the Philadelphia Athletics in six games. Rhem started Game Three and was the losing pitcher.

Undoubtedly the most amazing thing about that 1930 season for Flint was the famous “kidnapping,” which has gone down in baseball history. Apparently Gabby Street was not as successful as he hoped in helping Rhem. A wire-service story, published in the Atlanta Constitution on September 19, 1930, tells the tale. “Rhem, who through his diamond career has never been celebrated as an ardent prohibitionist, failed to appear at the Cardinals’ local headquarters [before a game in Brooklyn] on Monday night. Last night, however, he returned and faced ‘Gabby’ Street, the manager. ‘Yes?’ said Street coldly. ‘Yes,’ mumbled Rhem. ‘Bandits. Guns. Kidnapping. They made me drink the awful stuff.’ ” Rhem’s claim was that two thugs had kidnapped him and taken him to a remote roadhouse. They were armed, and forced him to drink a large quantity of hard liquor. “ ‘And I am sorry to say that I got drunk. Imagine that happening to me! Of all people, me! … I was helpless, always in fear of my life.’ ” 13

Apparently even the Cardinals management didn’t believe the story at the time, and Rhem later admitted to being drunk, but said that he had never left the hotel, and that Gabby Street had made up the story about the kidnapping.14 In any case, it was a media sensation, and was forever after everyone’s chief memory of Flint Rhem.

Rhem was back with the Cardinals in 1931, starting 26 of the 33 games in which he appeared. He ended the season with an 11-10 record and a 3.56 ERA. He also, however, gave up 17 home runs, the most in the NL. He went four innings in game two of a doubleheader against the Cubs on July 12 which broke all records for the number of doubles hit in a game and in a doubleheader. It seems that Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, designed to hold around 30,000 fans, was crowded with almost 46,000, of whom 8,000 were actually on the ballfield. Balls continually dropped into the overflow crowd, and were ground-rule doubles. There were 32 doubles hit in the two games, 21 of which came in the second game, which Rhem pitched. The Cardinals won that contest 17-13. Rhem fired a three-hit shutout against the Reds on September 6 to set the stage for a doubleheader sweep and push the St. Louis lead to seven games over the Giants. The Cardinals won both the pennant and the World Series. Rhem pitched just one inning in the Series.

Flint started out the 1932 season with the Cardinals. He went 4-2 before he and infielder Eddie Delker were sold to the Philadelphia Phillies in a cash deal on June 4.

Rhem’s drinking remained a problem. In his history of the Phillies, David Jordan quoted shortstop Dick Bartell as saying, “If he’d ever stayed sober, what a pitcher he could have been. He was the nicest guy in the world, never mean or nasty, never bothered nobody.”15 Despite his problems, Rhem posted an 11-7 record with the Phillies and had a 15-9 record for the year with a 3.58 ERA.This was the second of two seasons in which he would have 15 wins or more. By early August, Herbert Barker of the Associated Press was reporting that the “erstwhile play-boy of the St. Louis Cardinals” was having “the year’s greatest baseball comeback.”16

The comeback wasn’t to last, however. Flint was with the Phillies again in 1933, and had a record of 5-14 and an ERA of 6.62. Sometime during his tenure with the Phillies he managed to return to his South Carolina roots, striking out ten batters in six innings while pitching for Kingstree in an October game against Florence. To the delight of local fans, two other major-league pitchers, Van Lingle Mungo and Clise Dudley, also appeared in the game.

Before the 1934 season Philadelphia sold Rhem back to St. Louis. He appeared in only five games for the Cardinals, starting one and winning one. On June 23 the Cardinals sold him to the Boston Braves. On July 29 he pitched a one-hit shutout against Brooklyn. He appeared in 25 games for the Braves, 20 of which he started, but he was credited with only eight wins. Rhem’s combined record for the season was 9-8, with an ERA of 3.69.

Rhem was with the Braves again in early 1935, pitching in six games and posting a record of 0-5. On June 2 he was sent to Syracuse of the International League in exchange for pitcher Bob Brown. He appeared in 21 games for the Chiefs that year, with a record of 8-6. In December 1935 the Braves sold Rhem to the Cincinnati Reds, who put him on their Nashville farm team. He appeared in 13 games for Class A-1 Nashville in 1936, posting a record of 4-3. In mid-June, the Cardinals bought him from the Reds, and he pitched in ten games for St. Louis, starting four and winning two. His ERA was 6.75.

Rhem’s final appearance in the major leagues came on August 26, 1936. He was released by the Cardinals the next day. Over his 12 seasons in the major leagues, he pitched 1,725⅓ innings, and had a record of 105-97 and an ERA of 4.20. During his four different stints in the minors over the years, he pitched 655⅔ innings, with a record of 46-37 and an ERA of 3.91. He later said of his career, “I loved to travel. … Until I got into baseball, the biggest places I’d ever seen were Greenville and Columbia. Boy, New York floored me.”17 In March of 1936, Flint and Lula had their first and only child, Charles Flint Rhem, Jr.

Flint apparently tried to get back into baseball several times after that. In 1937 he attempted a comeback with the Lyman Pacifics of the Eastern Carolina League, and also appeared for the Kannapolis (North Carolina) Towelers. The Calgary Herald reported in June 1941 that he was trying to make a comeback with a South Carolina semipro team. Rhem signed up for the military draft in Georgetown, South Carolina, in 1942, but ended up pitching for the Bell bomber plant in Marietta, Georgia, during World War II.

Apparently that was Rhem’s last experience with baseball. He and his family settled in Greer, South Carolina, where his wife had a long career as a teacher. Flint had inherited a large tract of land in Williamsburg County, South Carolina, which he leased for farming and hunting. He routinely went there during hunting season to visit his brothers and sisters and to hunt and fish. He died in Columbia, South Carolina, on July 30, 1969, and was buried in Wood Memorial Park in Duncan. In 1993 he was posthumously inducted into the Greater Greenville Baseball Hall of Fame. Lula Rhem died in Greer, South Carolina, in 2001.

An updated version of this biography is included in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber.

Sources

Eisenbath, Mike, and Stan Musial, The Cardinals Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999).

Perry, Thomas K. Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880-1955. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004).

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Some correspondence and newspaper clippings were provided by Special Collections at East Carolina University.

Notes

1 Bob Broeg, Memories of a Hall of Fame Sportswriter (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1995), 47.

2 Broeg, 47.

3 Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), May 15, 1962.

4 “Charles Flint Rhem,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1969, 44.

5 Jack L. Hunt, “Remember When? Baseball Memories Abound.” Westminster News, February 9, 1994.

6 Ty Cobb and Al Stump, My Life in Baseball: The True Record (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1961), 212.

7 Letter from Ty Cobb to C.F. Rhem, Clemson University, dated May 10, 1923. Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections at East Carolina University.

8 Letter from Flint Rhem to Mrs. D.D. Rhem, dated only Sunday (1924). From the collection of East Carolina University.

9 “Flint Rhem Shows Promise of a Great Major Career,” Atlanta Constitution, May 24, 1925, B3.

10 Quoted in The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), 357.

11 “St. Louis Cards Send Flint Rhem to Millers,” (Associated Press) Milwaukee Journal, December 16, 1928, 14.

12 Unidentified clipping from the collection of East Carolina University.

13 “Imagine Me, of All People, Wails Flint Rhem as He Tells of Booze Seduction,” Atlanta Constitution, September 19, 1930, 17.

14 Neal Russo of the St. Louis Post Dispatch, quoted in “Rhem Kidnaped? A Hoax, he Confesses,” Baseball Digest, October, 1960, 16.

15 David Jordan, Occasional Glory: The History of the Philadelphia Phillies (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 75.

16 Evening Independent (St. Petersburg, Florida), August 2, 1932, 5.

17 The Sporting News, August 16, 1969, 44.

Full Name

Charles Flint Rhem

Born

January 24, 1901 at Rhems, SC (USA)

Died

July 30, 1969 at Columbia, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.