Frank Genins

Chris Von der Ahe, owner of the St. Louis Browns in 1892, was known for his irrational and confrontational behavior. Rookie Frank Genins had a puzzling run-in with Von der Ahe to start his career. According to a 1913 Baseball Magazine article by William A. Phelon, Genins was acquired from Omaha over the winter, but his major league debut was delayed by an illness.1 He finally made his first appearance on May 11 playing right field against Baltimore. The game opened with Jack Crooks “hitting a home run over the low fence in front of the Browns’ dressing room in right field.”2

Chris Von der Ahe, owner of the St. Louis Browns in 1892, was known for his irrational and confrontational behavior. Rookie Frank Genins had a puzzling run-in with Von der Ahe to start his career. According to a 1913 Baseball Magazine article by William A. Phelon, Genins was acquired from Omaha over the winter, but his major league debut was delayed by an illness.1 He finally made his first appearance on May 11 playing right field against Baltimore. The game opened with Jack Crooks “hitting a home run over the low fence in front of the Browns’ dressing room in right field.”2

In his story Phelon contends that Von der Ahe chastised Genins for the home run. Genins replied, “[H]ow could I help that… it went over the fence.” The owner said he faulted Genins for his attitude. In his heavy German accent, Von der Ahe wailed, “Ven dot ball went ofer dot fence how did you act…? Did you spring mit yourself against dot fence, und howl, und shake your fist…? No! You did not.”3 Phelon claimed that Von der Ahe released Genins on the spot. The release was actually filed on May 15 and, after a 10-day waiting period, Genins joined Indianapolis in the Western League.

Frank played second base for the Hoosiers and batted in the second spot for 20 games. His best day at the plate came on June 13 in a 9-5 win over Kansas City. He laced two doubles and a single and scored twice. Meanwhile Chicago and Pittsburgh were both eyeing him for their rosters. Pittsburgh thought they had acquired him, but Von der Ahe threw a curveball by claiming that he had never released Genins.

The matter was finally resolved by the league office. St. Louis had released him, but it was Cincinnati that quietly had signed him unbeknownst to Pittsburgh and Chicago.4 Frank joined the Red Stockings on the road and debuted for them at shortstop on July 5 in Philadelphia. The Phillies scored five times in the first on the way to a 7-3 win. Genins had poked two hits in May with St. Louis but went hitless against the Phillies while handling seven chances in the field.

He played 35 games with Cincy at shortstop, third base and the outfield. A .182 batting average sent him to the bench and brought his release in early September. Back in St. Louis, Pebbly Jack Glasscock was showing his age. The Browns resigned Genins and played him at shortstop in the last 14 games of the season. He struggled at the plate and in the field, making 14 errors and hitting just .170 in his second stint. Glasscock was retained for 1893, Genins was released.

Frank Genins was born on November 2, 1866, in St. Louis, Missouri. His parents, Frank and Frances (Vincent) Genins, were both born in France, which gave Genins’ his baseball nickname of “Frenchy.” Details of Genins’s family and schooling have proven to be elusive. Like a myriad of boys in the 1800s, he fell in love with baseball. Possessing speed and athleticism, he was playing with the Peach Pies amateur team in his late teens.

The Daily Review in Decatur, Illinois, hailed the Peach Pies as “the strongest amateur nine of St. Louis” when they came for a two-game series versus the Decatur town team.5 Genins and his teammates failed to represent their city; going down to defeat, 10-7 and 19-10. The latter game was farcical. The two teams combined for 28 hits and an astounding 54 errors. Genins was the shortstop for the Peach Pies, but, for reasons unknown, did not close out the season with the team, which played into November.

Omaha of the Western League brought in a contingent of St. Louis players for the 1887 season, including Genins, outfielder Herman Bader and catcher Charlie Krehmeyer. They reported in late March and were joined by left-handed pitcher Daniel O’Leary, who was not from St. Louis, but quickly became friends with the trio. The friendship of the quartet created a clique amongst the Omaha players and led to friction in the clubhouse. Whether this had an adverse effect on the team’s performance is impossible to determine.6

Genins was primarily the center fielder, but he did make appearances at second, third and short. The Topeka Golden Giants ran away with the pennant with Omaha struggling much of the season. They failed to have a pitcher with a winning record. For his part, Genins batted .320, the third-highest average for regulars (300 plate appearances or more) on the team.

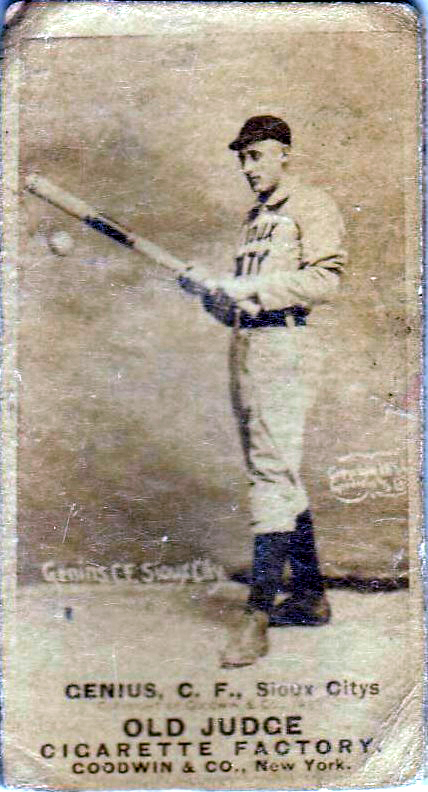

The St. Louis trio made their way west to Denver in the five-team Western League for the 1888 season. The league lasted only a few weeks. Bader and Genins hooked on with the Sioux City Cornhuskers, who assembled a roster from remnants of the Western League and other teams and entered the Class A Western Association on July 4. They lost their first three contests to league-leader Des Moines. The team reached fifth-place with a 13-14 mark before sliding back to the bottom of the standings.

Frenchy was second on the team in at bats but hit only .226. Splitting time in the infield and outfield, he had arguably his best day on July 26 in Milwaukee playing center field. Facing Clark Griffith, he slapped three hits, stole four bases and “gathered in four elegant drives to his territory.”7

Genins found a second home in Sioux City. He patrolled center field in 1889 and then fulfilled a utility role in 1890 and 1891. He became a fan favorite for his hustle and personality.8 He was popular with teammates, especially those who would join him on his off-day fishing trips. His best season at the plate came in 1889 as he banged out 30 extra-base hits to augment a .267 average. According to the Spalding Guide he batted .243 the following year in 120 games.9 In 1891 he hit .231.

Genins would winter in St. Louis at his parents’ home. Over the winter of 1891-92 there was speculation that he would sign with Cap Anson in Chicago, but he chose to sign with hometown St. Louis instead. After he struggled in the major leagues during 1892, he decided to play semi-pro ball in 1893 in the St. Louis area. He appears in box scores playing third base for the St. Louis Amateur Base Ball Club.

He was lured back to Sioux City for the 1894 season. His return was welcomed by the local press because he was “one of the most reliable and conscientious men who ever wore a uniform. He is… a brilliant outfielder.”10 Despite the glowing praise and frequent mentions, we are still uncertain how Genins batted. Given game accounts of where his hits landed, it appears that he batted right-handed, but the chance he was a switch-hitter cannot be ruled out.

After the pitching distance was finalized at 60 feet six inches, in 1894 batters put on a tremendous offensive display throughout baseball. In the National League, Hugh Duffy batted .440 and the Philadelphia Phillies produced four outfielders with batting averages over .400. The Western League was also a hitters’ paradise. The Corn Huskers featured 11 men with more than 100 at bats who topped the .300 mark. The pitchers were easy targets; Sioux City’s top three arms surrendered an average of 1.37 hits per inning.

Not surprisingly Genins put up the most impressive numbers of his career. He led the team with 45 doubles, which put him in the league’s top five. His team-leading 210 hits placed him tenth in the league. Genins crossed the plate an amazing 166 times, but that was second on the team and light-years behind Rasty Wright of Grand Rapids, who scored 217 runs.

Genins added 15 triples and 86 stolen bases, both impressive totals yet neither team-leading. He batted .374 for the champion squad. The Sioux City fans loved Genins, who sported a full mustache. At the end of the season he was presented with a medal to honor his fine play and mannerly human spirit. He received more than twice the votes that pitchers Bert Cunningham and Bill Hart garnered. The fans bid him adieu with heavy hearts but wished him well.

Newspapers had announced in August that he and two teammates had been acquired by the Pittsburgh Pirates for delivery after the conclusion of the season. The Western season ran into October, forcing Genins to report to manager Connie Mack in the spring. Neither Lew Camp nor Cunningham, the other two selected, ever played with Pittsburgh.

Genins became a role-player for the Pirates, playing every position except catcher and pitcher. He used his quickness to steal 19 bases in 73 games. At the plate he dropped down a team-leading 23 sacrifice bunts, a rate of one for every 13 plate appearances. The Pirates posted a 71-61 record which placed them in seventh place in the 12-team circuit.

Frenchy opened the season in the starting lineup, playing outfield and batting at the top of the order. Any chance he had of securing a permanent spot was dashed when he batted a lowly .159 to open the season. He pulled his average over the Mendoza line by mid-June and finished the season at .250. When in the lineup, Mack frequently used him as the number two hitter, which would account for the sacrifice total.

The Pirates loaned him to the Grand Rapids Gold Bugs of the Western League for the 1896 season. He played third base and outfield for the Bugs until they traded him to Columbus for Bobby Wheelock.11 With the Buckeyes he mostly played outfield with some work at shortstop. The Spalding Baseball Guide credits him with 124 games played and a .319 batting average.12

Ban Johnson was the magnate of the Western League. He and his owners seemed to have a knack for attracting players and keeping them in the league. Genins found a home with Columbus and remained with the team when it moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan, in July 1899. That franchise was then moved to Cleveland in 1900 when Johnson christened the circuit the American League. Genins was on the opening day roster for Cleveland when the American League became a major league in 1901.

During his tenure with Columbus they were known as the Buckeyes and the Senators. They finished seventh in 1896, but then rose to second place the following year. Genins batted .310 while playing third base and the outfield. In 1898 the team fell to fifth place and his batting fell off to .252. Frenchy was mainly a second baseman that season with some work in the outfield. In 1899 he split his time among the outfield, shortstop and third. According to the Spalding Baseball Guide he batted .277 in 125 games as the franchise finished in fourth place.13

In 1900 the Cleveland franchise was most often referred to as the Lakeshores. They finished in sixth place well behind the Chicago White Sox. Genins again accepted a utility role. Mainly an outfielder, he also played third, short and second. He batted .293, which placed him third behind Ollie Pickering and Candy LaChance on the squad. Pickering led the league in runs and hits.

The 1901 American League season began on April 24 in Chicago as the White Stockings entertained Cleveland before 9,000 fans. Genins played center field, batted third and went hitless in Cleveland’s 8-2 loss as all the other games in the circuit were rained out.14 Cleveland won their home opener on April 29 as Genins recorded a hit and scored a run in the 4-2 victory over Milwaukee.

On May 23 the Blues hosted Washington and found themselves trailing, 13-5, going into the ninth. With one out Pickering singled and improbably, the flood gates opened for the Cleveland offense. Genins supplied a single and came around to score. Pickering eventually scored the ninth run of the inning to give the Blues a 14-13 win. It proved to be Genins’s final major-league appearance. He headed west to Omaha and the Western League, joining them on June 7. A week later he was the hero in a win over Minneapolis when he delivered an eighth-inning base-loaded single.

A game story from late August casts some doubt upon our beliefs about Genins’s throwing hand. In the eleventh inning of a game, St. Joseph’s Tim Flood sent a drive to left center that looked like a clean gap-shot. Genins “started on the dead run and reached the ball safely with his right hand.”15 Right hand? Was he actually a lefty but played all those games in the infield? Did he snag the ball bare-handed? Or did the writer simply make a mistake? The St. Joseph Gazette-Herald offers no resolution. They simply stated that Genins reached up with one hand to pull the ball in.

The Omahogs finished fifth in 1901. They changed their name to Indians and rose to second place the following year, thanks to 27 wins from Mordecai Brown. In Genins’s final season with them, they fell into the cellar, winning only 49 contests. Frank was 34 when he joined them and was starting to slow down. Statistics for the 1901 season were in shambles and never submitted to publishers.

In 1902 Genins was predominately a third baseman with some outfield work. He batted .244 in 131 games. The following season he played 66 games in the outfield, 35 at shortstop and 13 at third base, according to the Reach Baseball Guide. His stolen bases fell off to 12 as he batted .252 and led the team in at bats.16

Now 37 and unwilling to call it a career, Genins headed south to join the New Orleans Pelicans in the Class A Southern Association for 1904 and 1905. The Pelicans were a veteran group with an average age of nearly 30. They battled for the pennant in 1904 but finished three games behind Memphis in a spirited race.

Genins captured the center field job and quickly became a fan favorite. One of his finer moments came on July 18 in a game against Atlanta. The Pelicans’ fans watched 13 and half innings of scoreless ball and, with the sun setting, witnessed Genins deliver the game-winning RBI. It brought twenty-five hundred fans to their feet as they “waved handkerchiefs and yelled themselves hoarse.”17 Genins did not remain in New Orleans for a series of exhibition games in September because of an illness in his family.18 He led the Pelicans in games played and batted .251.

Frenchy was back on Bourbon Street by mid-March of 1905. He played mainly first base in exhibitions games before drawing his release on May 12 with the Pelicans in first place after 17 games. He joined Meridian in the Class D Cotton States League. The local writers speculated he would play first base, but he immediately settled in at third base until the end of July when the league disbanded. From there, he went west to join the Oklahoma City Metropolitans of the Class C Western Association.

He stayed in the Western Association the following season, joining St. Joseph. The franchise moved to Hutchinson, Kansas, shortly after the season opened. At age 39 he was the veteran presence on the team and played 140 games at second base. He even took over the managerial duties late in the season. His first experience at the helm was challenging.

The Salt Packers were destined for last place and Genins felt they were given little respect in Topeka, home of the league champions. Each series against them brought controversy with the umpire. In early August, Genins had to put up with a rookie, one-armed umpire named Lewis “whose base ball knowledge was quite deficient.” Then on August 28 he pulled his team from the field because the umpire, listed as Dunn in the box score, was drunk. “His breath was so strong it pervaded the whole diamond.”19

As always Genins returned to St. Louis after the season. He had married Barbara Bourg in January 1897. Her father was French, her mother was from Luxembourg. The couple appears to have been childless; the available censuses do not list any offspring. When not playing baseball, Genins found work as a laborer. After his career he listed himself as a cooper (barrel maker/worker) on the census. He was working and had no intention of returning to the professional game in 1907 until he was contacted by the ownership of Dubuque in the Three-I League.

The Dubs were off to a dismal 1-10 start when Genins met with ownership. He accepted the managerial job and soon joined the team. He played primarily second base, but in August played shortstop and third. The season was a struggle; Genins batted only .193, but that was the sixth highest average of the 18 men who played for Dubuque. The team finished in the cellar with a mere 22 wins.

Pants Rowland was brought in to manage the following season and Genins was named captain of the team. They got off to an excellent start and stood atop the league at 19-10 after five weeks. In June Genins injured his foot and was forced to the bench. Eventually doctors told him to take the rest of the season off. After a short time at home, he returned to the league as an umpire in late August.

Tom Loftus was president of the Three-I League in 1908 and liked the way Genins handled himself as an umpire. Frank expected he would be rehired for 1909. Loftus was replaced over the winter and Genins was not offered a contract as umpire by the new leadership. In February he was hired to manage the Freeport, Illinois Pretzels in the Class D Wisconsin-Illinois League. The board of directors of the Pretzels reportedly offered him $225 a month, a $25 raise over his Dubuque salary.20

Working from his St. Louis home and calling upon all the contacts he had in baseball, Genins assembled a roster for Freeport that included a youthful Fred Luderus and a St. Louis colleague who had been playing as long as Genins, Fred Betts. Unfortunately, they were the only bright spots for a team that struggled from their first exhibition game, a loss to Dubuque.

Speculation that Genins would be fired began in mid-June and finally on July 9 he played/managed his last contest for Freeport. Ed Lewee came from Peoria to replace him and Genins headed to Racine to play second base for the Belles.21

Approaching his 43rd birthday, Genins regained his youth briefly with the Belles. On September 3 he drove the ball deep to left field in Racine’s League Park and circled the bases for a homer, “the first one of the kind ever made on the grounds.”22 On September 8 he played his last game before the home fans. He punctuated his brief time in Racine by driving home the winning run in the ninth to beat Freeport.23

Genins signed to umpire in the Three-I League in 1910. His career came to a screeching halt in June in Davenport, Iowa. In the first game of the series with Springfield, he incited the fans with missed calls. The next day he was rudely welcomed by a crowd calling him a “polecat” and berating him with verbal abuse. According to the local paper, his second outing was no better as he missed an obvious call at first and then allowed a batter for Springfield four strikes.24 For the second day in a row he had to be escorted to safety. He was relieved of his umpiring duties the next day and returned to St. Louis, where he played semi-pro baseball.

In 1911 he umpired in the St. Louis area and again felt the wrath of fans. He had to be escorted from a game by the local police on at least one occasion. Nevertheless, he kept with it and in 1914 he umpired in the Central Association before leaving the diamond for good.

Genins passed away at his home from peritonitis caused by a perforated ulcer on September 30, 1922. Funeral services were held at the home and the body was then sent to the Missouri Crematory. A source on ancestry.com says that his remains were then placed in the New San Marcus Cemetery near St. Louis on July 1, 1924.25 His wife remarried and died in 1957. She is buried in the same cemetery as Frank.

Genins enjoyed a reputation as a personable, hard-working, popular player. The accolades for his work in center field were numerous and call into question why so many managers used him in the infield during his prime. The Sioux City fans felt that in center field he “would take care of anything that came his way.”26 Genins’s versatile talent made him a welcome addition to teams because of his ability to play many positions. A manager, however, must have been in a desperate situation to move one of the game’s finest fly hawks into the infield. In later years he was content at second base, knowing his ability to cover large, open spaces was gone.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Records for Western League seasons are taken from “The Western League” by Madden and Stewart. Statistics are from Baseball Reference.com unless otherwise noted. Standings come from “The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, first edition.”

Notes

1 William A. Phelon, “Thirty Days of Baseball History,” Baseball Magazine, March 1913: 16.

2 “Another Oriole Victory,” The Baltimore Sun, May 12, 1892: 4.

3 Phelon, “Thirty Days…”

4 “Von Der Ahe’s Latest, Pittsburgh Dispatch, June 29, 1892: 8.

5 “Base Ball News,” The Daily Review, June 6, 1886: 2.

6 “Willow and Sphere,” Lincoln Evening Call (Lincoln, Nebraska), July 6, 1887: 4.

7 “The Cream City Club,” Sioux City Journal, July 27, 1888: 2.

8 W.A.Winston, “In the Field of Sport,” Sioux City Journal, August 2, 1908: 11.

9 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1891, (Chicago: A.J. Spalding and Bros., 1891), 140.

10 “Chatter of the Sports,” Sioux City Journal, March 4, 1894: 7.

11 “Mack’s Men Going West,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 22, 1896: 6.

12 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1897, (New York City: American Sports Publishing Company, 1897), 144.

13 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, (New York City: American Sports Publishing, 1900), 145&148.

14 “The Season is Open,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 25, 1901: 7.

15 “Saved at Eleventh Hour,” Omaha Daily Bee, August 29, 1901: 4.

16 Reach’s Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1903, (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Publishing, 1903), 192-196.

17 “Play Fourteen Innings,” Times-Democrat (New Orleans), July 19, 1904: 9.

18 “Benefit a Winner, Times-Democrat, September 29, 1904: 9.

19 “How Genins Views It,” The Hutchinson (Kansas) News, August 29, 1906: 7.

20 “Frank Genins Signs to Manage Freeport Team,” The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois), February 6, 1909: 8.

21 Freeport played poorly but maybe it wasn’t all Genins’s fault. During the time period he awaited his release newspapers offered up at least four men who were going to be the new manager. Either the writers had no reliable sources, or the ownership was very indecisive.

22 “Sporting World,” The Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), September 4, 1909: 3.

23 “Sporting World,” The Journal Times, September 9, 1909: 3.

24 “Hillary Injured and Out of the Game,” Quad City Times (Davenport, Iowa), June 2, 1910: 6.

25 Find-a-Grave https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3109471. There is a second version of him on this site and it says the location of his ashes is uncertain. Last accessed on May 5, 2019.

26 “Frank Genins, Veteran of Packers, Succumbs,” Omaha World-Herald, October 1, 1922: 11.

Full Name

C. Frank Genins

Born

November 2, 1866 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

September 30, 1922 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.