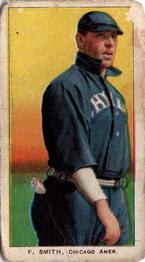

Frank Smith

Frank Elmer Smith, known during his playing days as the “Piano Mover” because he used to boast that he could “carry a baby grand up four flights of stairs without a rest,” was a mainstay of the Chicago White Sox pitching staff between 1904 and 1909, winning 104 games for the club during that span. Relying on a drop ball, curve, and occasional spitball, Smith hurled two no-hitters for the White Sox, the only pitcher in franchise history to do so, and led the American League in both innings pitched and strikeouts in 1909.

Frank Elmer Smith, known during his playing days as the “Piano Mover” because he used to boast that he could “carry a baby grand up four flights of stairs without a rest,” was a mainstay of the Chicago White Sox pitching staff between 1904 and 1909, winning 104 games for the club during that span. Relying on a drop ball, curve, and occasional spitball, Smith hurled two no-hitters for the White Sox, the only pitcher in franchise history to do so, and led the American League in both innings pitched and strikeouts in 1909.

Smith, who during his prime stood a shade under 5’11” and weighed in at a hefty 194 pounds, was born in Pittsburgh on October 28, 1879, to a family whose original name was Schmidt. He briefly attended and coached at Grove City College before he signed on with his first professional team in Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1900.

After a stint with the Raleigh Senators of the Virginia-North Carolina League in 1901, Smith was promoted to Birmingham in the Southern League for the 1902 season, where he acquired the nickname “Nig” due to his dark complexion. Smith was a terrific power pitcher for Birmingham, and was described as “a big hulk” who had tremendous back and shoulder muscles “super induced by his piano pulling proclivities.” During every off-season Smith worked as a furniture mover for his father and this contributed to his prowess on the mound. Eventually he caught the attention of Charles Comiskey and Smith was drafted by Chicago for the 1904 season.

Smith won 16 games for the White Sox in his rookie campaign, a season in which he acquired a new pitch, the spitball. Along with Ed Walsh, Smith was tutored on the pitch by Elmer Stricklett, a minor league prospect for the White Sox. Stricklett showed Walsh and Smith how to put spit on the ball and throw it like a fastball, producing a pitch with tremendous speed but little rotation, giving it the effect of a knuckleball.

At times Smith was able to master the spitball during a brilliant 1905 season when he went 19-13 with an ERA of 2.13. Late in the season, on September 6, the White Sox traveled to Detroit for a doubleheader against the Tigers on a Wednesday afternoon. 3500 fans in Bennett Park watched the White Sox defeat the Tigers 2-0 in the first game, and then saw Smith throw just the fifth no-hitter in American League history. Smith was staked to an eight run lead thanks to five walks, five errors and one hit in the top of the first inning. Detroit’s starting pitcher, Jimmy Wiggs, was replaced by George Disch for the second inning but the White Sox pounded out 11 hits and seven runs over the next eight innings. Meanwhile the Piano Mover was putting together a gem. He struck out eight and walked three and retired the last 17 Tiger batters in order to preserve the no-hitter. In fact, the 15-0 drubbing of the Tigers remains the most one-sided no-hitter in American League history.

The first ever one-city World Series between the White Sox and their cross-town rivals the Cubs highlighted the 1906 season. Smith contributed very little to the team that year, posting a 5-5 record in 13 starts, and in fact was kept out of the rotation by Sox manager Fielder Jones for weeks at a time so that Smith could conquer his problems controlling the spitter. Late in the season, The Piano Mover was able to get his spitter over the plate. He was used mostly in relief down the stretch and saw no action in the White Sox’ World Series triumph. He returned to form the following year, however, as he compiled a 23-10 record while striking out 139 batters in 310 innings pitched, though Chicago lost the pennant to Detroit during the final week of the season.

Conflicts between Smith, Comiskey and Jones led to Smith deserting the ball club and returning home to Pittsburgh on June 14, 1908. Always the sensitive type, Smith was offended by Comiskey’s constant criticism of Smith’s lack of control and outraged by Jones’ insinuation that Smith was drinking too much. The Chicago Tribune reported that “Prior to departing for Pittsburgh, Piano Smith went in to give Mr. Comiskey a hard call down. Before Smithy could open his flow of language the boss said, ‘You’ve been threatening to quit for two years. Now then, pack up your duds and dig and I don’t care if you never come back.’ The pianist was peeved because he was asked to practice control and other things.” Upset that Smith consistently missed the Sox’ morning practices, Comiskey felt that Smith had an obligation to follow team rules regardless of the player’s personal issues. Comiskey “declares he is the boss, and that Smith, if he has gone, has left because he would not obey orders,” reported the Tribune on June 21. The White Sox were in first place at the time of Smith’s departure.

As the White Sox headed for home after an east coast trip late in July, rumors persisted that Smith was going to rejoin the team. On July 25, 1908, the Chicago Tribune reported that “according to the dope, Mr. F. Smith, the prodigal piano mover is about to burst upon the job once more. He was to have met the team at Cleveland with his mouth wide open for a feed of the justly celebrated husks. Smith so often declared he never would return that Jones applied reverse English to the declaration and told Smith to come on as far as Cleveland, anyhow. Moving the kind of pianos they have at Allegheny, Pa., sounds poetical and all that, but, strong as he is, the esteemed Smithy couldn’t kick in $125 per week at the job. Moving a baseball with saliva on it is much easier, the distance is shorter, as a rule, and there is no expense on the side for horse feed and axle grease.”

After Smith was reunited with Ed Walsh, the pitching tandem kept the Sox afloat for the rest of the season, combining for 43 starts and often relieving each other late in games. Smith won 11 games after he returned and even though he injured a finger on his pitching hand trying to stop a hot shot in Cleveland on September 13, he pitched his second no-hitter a week later. Smith held the visiting Philadelphia Athletics hitless through nine innings, before Chicago finally pushed across a run in the bottom of the ninth. Frank Isbell led off for Chicago and reached first on a grounder deflected by first baseman Danny Murphy. After Isbell advanced to third, Connie Mack ordered the next two Chicago batters, George Davis and Freddy Parent, intentionally walked. On the third outside lob to Parent, the infielder “grasped his bat as near the tip of its handle as he dared, and reached for that ball.” One account had Parent stepping across the plate, but his tapper to second baseman Scotty Barr resulted in Isbell scoring the game’s only run on a close play at home, giving Smith his second career no-hitter in a thrilling 1-0 win. The season, however, ended on a sour note as the White Sox lost the pennant on the season’s final day and finished in third place.

Under new manager Billy Sullivan, Frank Smith hit his stride in 1909. He pitched 365 innings, striking out 177 batters with an ERA of 1.80. He finished 25-17 that year, his most wins in the majors. Smith opened the 1910 season with an opening day one-hitter against St. Louis but his better days were behind him and on August 11 he was traded to the Boston Red Sox, who had high hopes for him. The Red Sox owner, John Taylor called Smith the “hope” of the team and felt that the 1911 season “depends on Frank Smith to live up to his reputation” and prove himself one of the best pitchers. Taylor even offered a bonus to Smith for winning a certain percentage of games. Smith never responded and appeared in only five games for the Red Sox, who, frustrated with his drinking, washed their hands of him and sold him to the Cincinnati Reds on May 11, 1911, for $5,000.

Smith did pitch in 42 games for the Reds, compiling a record of 11-15 in 1911 and 1912 but in June of the latter year Cincinnati sold him to Montreal where he finished out the season. In 1914 at the age of 34 he joined the Baltimore entry in the upstart Federal League and pitched reasonably well, posting a 14-12 record before he hooked on with the FL Brooklyn Tip Tops, where he finished out his career in 1915 with a 5-2 record in 63 innings pitched.

After he retired from baseball, Smith returned to the moving business in Pittsburgh. He died in his home on November 3, 1952 at the age of 73. Smith had succumbed to complications of Bright’s disease, a chronic kidney ailment that is known as nephritis today. He was survived by his wife Rena Shriner Smith, his son Frank Jr., two grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. He is buried in Minersville Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Frank Elmer Smith

Born

October 28, 1879 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

November 3, 1952 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.