Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas played during an era when team owners looked upon their players as chattels. By their standards, Frank Joseph Thomas was considered a rebel. Much of his career was spent bickering with management over his worth to them. In his early career with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Thomas’s adversary in such battles was the man sometimes called “El Cheapo,” otherwise known as Wesley Branch Rickey.

Frank Thomas played during an era when team owners looked upon their players as chattels. By their standards, Frank Joseph Thomas was considered a rebel. Much of his career was spent bickering with management over his worth to them. In his early career with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Thomas’s adversary in such battles was the man sometimes called “El Cheapo,” otherwise known as Wesley Branch Rickey.

During the 1950s Thomas’s demands were considered selfish but by today’s standards they would be probably be considered reasonable. His negotiations with Branch Rickey became legendary around the Steel City. In 1955 Thomas was the lone holdout on a Pirates club that was coming off a last-place finish 44 games behind the New York Giants. Rickey could not believe that this young man would have the audacity to challenge a $2,000 raise, from $13,000 to $15,000. The slugging outfielder sought a salary of $25,000 after a 1954 season in which he belted 23 home runs and drove in 94 runs with a career-high batting average of .298. On top of that, he received 24 votes for Most Valuable Player on a team that lost 101 games.

What Thomas should have realized was that he was dealing with the same general manager who reportedly informed future Hall of Famer Ralph Kiner, after Kiner won his seventh consecutive home run title in 1952, “We finished in last with you, we can finish last without you.” When Thomas held out for 17 days in 1955, he kept in shape by working out at the University of Pittsburgh. While he did not get the $25,000 he wanted, he did get a raise that brought his salary to $18,000. This compromise did not sit well with Mr. Rickey.

Frank Thomas, a late-season acquisition by the 1964 Phillies, grew up in the shadow of Forbes Field. Born in Pittsburgh on June 11, 1929, he entered a seminary in Niagara Falls, Ontario, as a teenager to study for the priesthood but could not shake an itch for baseball, and he decided to forgo a career in the priesthood. Frank’s father was Bronaslaus Tumas, a Lithuanian who had immigrated to the United States in the early 1900s. He lost his right arm in a work accident, and was employed as a foreman for the laundry department at Pittsburgh’s Magee Hospital. His mother was Anna Marian Thomas, a homemaker from Johnstown, Pennsylvania. He had three siblings — an older sister, Delores, and the younger Marie and John.1

Thomas’s professional career began in 1948 when the Pirates signed him and sent him to Tallahassee of the Class D Georgia-Florida League. He played in the outfield, made the league all-star team, and led the league in RBIs with 132. He moved up to Class B Waco and Davenport in 1949 and then Class A Charleston and Double-A New Orleans in 1950.

In 1951 the Pirates invited Thomas to spring training for the third straight season. Eventually they returned him to New Orleans. He was selected to play the outfield in the Southern Association all-star game, and his play that season (.289, 23 home runs) earned him his first late-season audition with the parent club.

Thomas made his major-league debut on August 17, 1951, at Forbes Field against the Chicago Cubs. He started in center field and batted third in the order. He got his first hit, an RBI double off Paul Minner, in an 8-3 Pirates win. He was 1-for-4. On August 30 he hit his first major-league home run, off George Spencer of the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds in New York.

The next year Thomas went back to New Orleans for more seasoning. His manager was Danny Murtaugh, the future leader of two World Series-winning teams. “I guess that it was good luck in disguise because I had one heck of a year,” Thomas said in 1990.2 He again was picked for the all-star game and led the league in homers with 35, scored 112 runs, and collected 131 RBIs while batting .303. On August 6, 1952, a sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Press asked why Thomas was still in the minors, especially when the Pirates were in dire need of hitting, and Rickey was hard-pressed to answer. Thomas was finally brought up in mid-September, played in six games and managed two singles. Although he played in only six games, Thomas felt that he had finally earned a spot on the team.

Thomas stayed with the Pirates in 1953. He had been paid $6,000 in New Orleans in 1952, and he requested an additional $1,000 from the Pirates. Rickey’s response was said to be, “I can’t pay major-league salaries to minor-league players.” Fred Haney, the Pirates’ manager, assured the youngster that he would get every opportunity to prove himself at the big-league level. Thomas responded with 30 home runs and 102 RBIs.

Thomas became a regular after the Pirates traded Ralph Kiner to the Cubs in June 1953. When Kiner departed, so did Kiner’s Korner — previously known as Greenberg Gardens — which had shortened the outfield fences by 30 feet, from 365 feet to 335. Thomas later figured that had the shorter wall remained, his home-run totals would have doubled and most likely he would have finished his career with more than 500. The wall was highly unpopular with the Pirates’ pitching staff. Pitcher Murry Dickson (66-85 with the Pirates in 1949-53) once said ruefully, “With some justification, the ‘Greenberg Gardens’ was largely responsible for my record.”3

After his successful first full major-league season, Thomas told Rickey, “I’m a major leaguer now and want to be paid accordingly.” Rickey asked him how much he wanted and Frank said $15,000. This did not set well with the Mahatma, who paused, thought about it and suggested, “You go along with my offer of $12,500 and if you have another good year, I’ll take good care of you.”4 Against his better judgment, Thomas accepted.

In 1954 Thomas batted.298 with 23 home runs and 94 RBIs. He went to Rickey expecting a substantial increase for 1955 but was offered $15,000 and was then compared negatively with Ralph Kiner. “If you are going to compare me, give me the same opportunity,” Thomas replied. “Put back Greenberg Gardens for me and I’ll hit you 50 homers because I can tattoo the scoreboard.” Thomas refused to sign Rickey’s contract and became a holdout. Rickey warned him, “Go ahead and hold out. I’ll keep you out of baseball for five years.”5 Thomas succeeded in getting the team’s offer up to $18,000, and he reluctantly signed, then proceeded to have his one bad season for the Pirates: 25 home runs, 72 RBIs, and a batting average of .245.

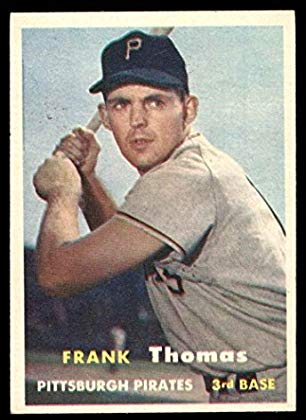

In 1956 Joe Brown became the Pirates’ general manager. That season Lee Walls played a lot of left field, so Thomas moved to third base at the request of manager Bobby Bragan. Bragan appreciated his athleticism and remarked, “He was our long-ball man, but he was a team player and had great hands.” Although he struggled defensively, Thomas played in 157 games, ties included, batted .282, and had 25 home runs and 80 RBIs. Brown offered a $1,000 raise for 1956, which Thomas accepted.

In 1957 Thomas played in 151 games, split among first base, third base, and the outfield. He enjoyed a decent season: a .290 batting average, 23 home runs, and 89 RBIs. Brown raised his salary to $25,000 for 1958.

The Pirates slugger was worth the investment. He had the best year of his career in 1958,with 35 home runs and 109 RBIs. On August 16 Thomas clouted three consecutive home runs against the Cincinnati Reds. At last he seemed happy. He enjoyed the new California venues of Seals Stadium in San Francisco and the Los Angeles Coliseum. He especially enjoyed the new home of the Dodgers and loved taking aim at the Coliseum’s short left-field fence. He predicted that if he played in Los Angeles, he could challenge Babe Ruth’s single-season record of 60 home runs. Thomas started the All-Star Game at third base and said this was his proudest accomplishment, since the players chose the starters.

The Pirates slugger was worth the investment. He had the best year of his career in 1958,with 35 home runs and 109 RBIs. On August 16 Thomas clouted three consecutive home runs against the Cincinnati Reds. At last he seemed happy. He enjoyed the new California venues of Seals Stadium in San Francisco and the Los Angeles Coliseum. He especially enjoyed the new home of the Dodgers and loved taking aim at the Coliseum’s short left-field fence. He predicted that if he played in Los Angeles, he could challenge Babe Ruth’s single-season record of 60 home runs. Thomas started the All-Star Game at third base and said this was his proudest accomplishment, since the players chose the starters.

The comfortable feeling came to an end on January 30, 1959, when the Pirates traded Thomas and three other players to the Cincinnati Reds for catcher Smoky Burgess, pitcher Harvey Haddix, and third baseman Don Hoak. The trade would go down as the worst in Reds’ history and many, including Thomas, believed it was responsible for the Pirates’ World Series championship in 1960. Before Thomas signed his contract, he informed Reds general manager Gabe Paul that he had a bad hand that was not healing properly. Paul was not worried; Frank asked for a salary of $40,000, which he got. The hand really bothered him and affected his play. The pain brought tears to his eyes whenever he applied pressure. Both of the Reds managers that year, Mayo Smith and Fred Hutchinson, had him on the bench a lot. A doctor later discovered that tumors were growing on the nerves of his hand. This did not save Thomas from being traded for the second time in a year. On December 6, 1959, he was shipped to the Cubs for outfielders Lee Walls and Lou Jackson and pitcher Bill Henry.

Thomas had surgery on his hand and had only a fair season with the Cubs: a .238 batting average, 21 homers, and 64 RBIs in 479 at-bats. He had a couple of run-ins with manager Lou Boudreau that left Thomas feeling that Boudreau was trying to show him up.

One time in Los Angeles, general manager John Holland offered Thomas $1,000 if he would work with and coach the younger players. Thomas refused, but the GM stuck the money in Thomas’s shirt pocket. Two weeks before the end of the season, Holland gave him another $2,000. Suspecting something, Thomas told management, “If my contract for the coming year includes a cut in my salary, you are going to hear from me.”6 He was right; his salary was cut by $8,000. Frank wrote a ten-page letter to Holland saying he felt the Cubs were trying to buy him off. Holland offered to take back the $3,000 and not cut his salary, which he did. Thomas gained a tremendous amount of respect for the GM, feeling Holland was fair and someone whom he could talk to.

Thomas’s next stop was Milwaukee. On May 9, 1961, as he was on the team bus heading to a game with the Braves, he was informed that he would be switching uniforms when the team arrived. He walked into the dressing room and was greeted by his new manager, Charlie Dressen, who told him that he would be the regular left fielder. Thomas performed well in a lineup with Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Joe Adcock. In fact, on June 8, 1961 at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, that quartet became the first in major-league history to hit home runs in consecutive at-bats, and Thomas established the mark as the fourth of them. He enjoyed a productive year, batting .284 and smacking 25 homers. General manager John McHale informed Thomas he wanted him back for 1962, but in November the Braves traded him to the brand-new New York Mets. He tried to get in touch with McHale but the Braves GM never returned his calls. Thomas’s comment: “General managers treated players like slaves.”7

At 33, Thomas had one of his best offensive years for the expansion Mets in 1962, hitting 34 home runs. “We had a veteran ballclub, with many players from winning traditions.”8 Thomas and his teammates felt that they would have a fair record. But the pitching quality did not match the team’s hitting capability. This team lost a record-setting (for the modern era) 120 games.

Thomas loved playing in New York. The fans were great. They had been hungry for a National League team ever since the Dodgers and Giants left for California after the 1957 season. Said Thomas, “I had fun on the Mets,” a team whose fans took them into their hearts and forgave everything. No team got more enthusiastic support. In addition to the fan support, Casey Stengel took the media pressure off them. He entertained both the fans and the press with his “Stengelese.”

Thomas had several power outbursts in 1962; during one three-game stretch, he hit six home runs. Because he had star status in New York, he hoped that he would make a lot of money in endorsements, but his endorsement money amounted to just $2,000. In 1963, while he was still productive, hitting .260 with 15 home runs, he got caught in a roster squeeze as the Mets gave playing time to younger players like Ed Kranepool. Thomas became expendable and a good target for a contending team. In 1964 such a deal occurred.

On August 7, 1964, Thomas was traded to the Phillies for prospects Gary Kroll and Wayne Graham, and cash. It was the first time Thomas played for a serious contender. After the trade, Philadelphia expanded a 1½-game lead to 6½ games. On September 8 Thomas fractured his right thumb sliding into second base. As Jim Bunning recalled, a ball was hit to the left of Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills. Thomas faked a break for third in hopes of distracting Wills but then had to dive back to second and broke his thumb. He played the rest of the game and reached base twice, but then sat out the next 16 games. By the time he returned in late September, the Phillies’ inglorious collapse was almost over. In 39 games for Philadelphia, he hit seven home runs and batted .294

On July 3, 1965, an incident of pregame horseplay occurred around the batting cage between Frank and Richie Allen before a contest with the Cincinnati Reds. Several versions of what happened have been given. The website www.BaseballLibrary.com states that Thomas swung a bat at Allen during a disagreement. It has been said that Thomas used racial slurs; both would “bury the hatchet” years later. Whatever happened, Allen belted a three-run triple in the seventh inning and Thomas hit a pinch-hit home run to tie the score in the eighth. The Reds eventually won, 10-8. After the game the Phillies sold Thomas to the Houston Astros. He played in 23 games for the Astros and and then was sold to the Milwaukee Braves, for whom he played 15 games. In April 1966 he was released by the Braves (now in Atlanta) and in May he signed with the Cubs. He played in five games with the Cubs and 25 with their Tacoma affiliate before he was released. He retired then, with Frank’s career totals for 16 years in the majors of 1,766 games, 1,671 hits, 286 home runs, 962 RBIs, and a batting average of .266.

Frank married the former Dolores “Dodo” Wozniak in 1951. She died of pancreatic cancer in 2012. They had eight children: Joanne, Patty Ann, Frank W., Peter, Maryanne, Paul, Father Mark, and Sharon (deceased), and as of 2013, 15 grandchildren. As of early 2013, he lived in Ross Township, Pennsylvania, just outside Pittsburgh, and spent time playing in charity golf tournaments. He used to play in old-timer’s games in Pittsburgh when they had them. Thomas is a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Alumni Association and has participated in a number of fantasy baseball camps. As a 65-year-old during the 1994 All-Star festivities at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, he drove one deep into the gap.

He once summed up his attitude about life: “I always felt if you gave 100 percent at whatever you did, you didn’t have anything to be ashamed of.”9

Postscript

Thomas died at the age of 93 on January 16, 2023.

Sources

Finoli, David, and Bill Ranier, The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2003).

Golenbock, Peter, Amazin’ (New York: St. Martins Press, 2002).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd edition. (Durham, North Carolina: Interlink Publishing, 1997).

Kuklick, Bruce. To Every Thing a Season (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991).

O’Brien, Jim. We Had ’Em All the Way, Bob Prince and His Pittsburgh Pirates (Pittsburgh: Geyer Printing, 1998).

O’Toole, Andrew, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000).

Peary, Danny. We Played the Game (New York: Hyperion, 1994).

Thomas, Frank, Ronnie Joyner, and Bill Bozman, Kiss It Goodbye! The Frank Thomas Story (Dunkirk, Maryland: Pepperpot Productions, 2005).

The Baseball Encyclopedia, Eighth Edition (New York: Macmillan, 1990).

Emert, Rich. “Where Are They Now? Frank Thomas.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (online) accessed April 17, 2003.

Baseball Almanac, www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php/p=thomafr03.

Frank Thomas, BaseballLibrary.com, www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/ballplayers/T/Thomas_Frank.stm.

Friend, Harold. Frank Thomas interview. “The Highlander, Official E-Newsletter of Baseball Fever’s NY Yankees Forum”, Volume 13. March 2004

Robinson, James G. “Break Up the Mets.” BaseballLibrary.com: www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/features/flashbacks/o4_23_1962.stm.

Ultimate Mets Database: www.ultimatemets.com/profile.php/PlayerCode=0008.

www.angelfire.com/ny5/thehighlnder/Highlander13page3.htm.

Personal letters between Frank Thomas and Bob Hurte, 1992-2004.

Notes

1 Frank Thomas, Ronnie Joyner, and Bill Bozman. Kiss It Goodbye! The Frank Thomas Story (Dunkirk, Maryland: Pepperpot Productions, 2005), 1,2.

2 Danny Peary, We Played the Game (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 190.

3 Andrew O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 97.

4 Peary, 226.

5 Peary, 292.

6 Peary, 463.

7 Peary, 503.

8 Peary, 541.

9 Rich Emert. “Where Are They Now? Frank Thomas.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (online), accessed April 17, 2003.

Full Name

Frank Joseph Thomas

Born

June 11, 1929 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

January 16, 2023 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.