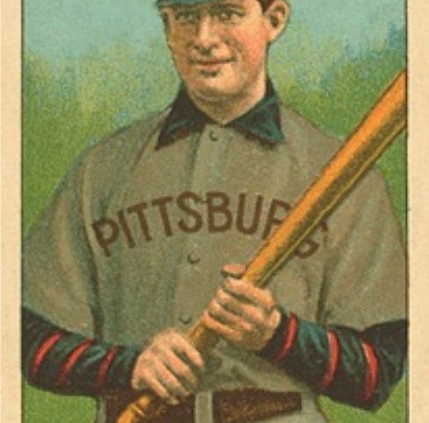

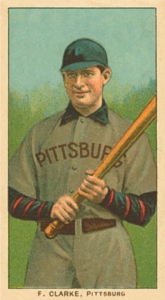

Fred Clarke

Fate: “The supposed force, principle, or power that predetermines events.”[1] Some people believe in it, some do not, though no one can be certain of its existence. But Fred Clarke was a believer in fate. In an interview with a reporter from the New York Herald in 1911, Clarke admitted, “I attribute my success to fate. … Life is a funny game, and a little thing, almost a trifle, may make a splash in your affairs so big that the ripples from it will be felt as long as you live.”[2] Skeptics might write off Clarke’s words as the ramblings of a highly successful sports figure exuding false modesty as he nostalgically looked back on his career. However, a close study of Clarke’s life shows that the fiery player-manager may have had a better feel for what was happening to him than any skeptic could imagine.

Fate: “The supposed force, principle, or power that predetermines events.”[1] Some people believe in it, some do not, though no one can be certain of its existence. But Fred Clarke was a believer in fate. In an interview with a reporter from the New York Herald in 1911, Clarke admitted, “I attribute my success to fate. … Life is a funny game, and a little thing, almost a trifle, may make a splash in your affairs so big that the ripples from it will be felt as long as you live.”[2] Skeptics might write off Clarke’s words as the ramblings of a highly successful sports figure exuding false modesty as he nostalgically looked back on his career. However, a close study of Clarke’s life shows that the fiery player-manager may have had a better feel for what was happening to him than any skeptic could imagine.

Born on a farm near Winterset, Iowa, on October 3, 1872, Fred (not Frederick) Clifford Clarke was the ninth of 12 children[3] of William D. and Lucy (Cutler) Clark or Clarke, depending on the source,[4] and the older brother of major league outfielder Joshua “Pepper” Clarke.[5] In 1874 or 1875,[6] Clarke’s father, a blacksmith and a farmer,[7] moved his family by covered wagon to a farm in Cowley County, Kansas, about four miles north of Winfield, an area that Clarke came to love and not far from where he would eventually establish his Little Pirate Ranch.[8] It was in this area that Clarke was first educated, attending a country district school.[9] Five or six years after the move, William Clarke uprooted his family again and returned to Iowa, settling in Des Moines.[10] The young Fred transferred to the Dickenson public schools [11] and, in the 1880s, started delivering papers for the Des Moines Leader, whose city circulator was Ed Barrow, the future major league baseball executive and Hall of Famer.[12] It was also in the 1880s that Clarke became enthralled with the game of baseball by watching the stars of the Des Moines teams.[13]

What followed was Clarke’s orderly but relatively fast rise from being a spectator to playing major league ball. In 1889 and 1890, Clarke first participated in organized amateur baseball as a second baseman and substitute catcher on the Des Moines Mascots, a team for which Barrow served as general manager.[14] The following season, he moved up a level by playing semiprofessional ball with the Carroll, Iowa, team,[15] and in 1892, he began his professional career with Hastings of the Nebraska State League.[16]

There are at least several different versions of the story of how Clarke got his start in the professional ranks, each involving its own twist of fate.[17] But whatever brought Clarke to Hastings, once he was there, he proved that he was an offensive threat, hitting .302 with 25 runs scored and 14 stolen bases in only 41 games.[18] As for his defensive play, Clarke described it best in an article published in the January 17, 1946, issue of The Sporting News:

They put me in the outfield, and I was lucky to catch half of the drives hit to me. … An old-timer told me I could improve by practice, so I went out to the field at 8 o’clock in the morning and practiced until game time in the afternoon. After a while, I got so I could catch fly balls pretty well.[19]

During the next two years, two seemingly unsuccessful and unrelated events in Clarke’s life resulted in pushing him to the place where he would gain his greatest fame—the National League—and might have reinforced Clarke’s belief in fate. The first event occurred at the close of the 1893 season—a season that saw Clarke splitting his ball-playing time with St. Joseph of the Western Association and Montgomery of the Southern League. Perhaps frustrated because the three teams that he had played for were each put out of business when their leagues either collapsed (Hastings and St. Joseph) or were suspended because of a yellow fever outbreak (Montgomery), Clarke attempted to stake a claim in the Cherokee Strip, a section of land in what is now Oklahoma,[20] and get out of professional baseball. However, fortunately for the baseball world, he failed, prompting him to take another chance at trying to make a living playing ball and thus pushing him into the second event.

This event happened the following season when the Southern League’s Savannah club, on which Clarke was the starting left fielder, disbanded on June 27. Clarke was all set to go to Milwaukee to play for yet another minor league team, when the Louisville Colonels of the National League expressed an interest in him and sent him transportation money before Milwaukee’s arrived. Hoping that this would be his big break and encouraged by John McCloskey, Clarke’s manager at Montgomery and Savannah and someone who recognized Clarke’s major league potential, the young outfielder accepted the Colonels’ offer and headed to Kentucky.[21]

Once in Louisville, Clarke proved that McCloskey’s assessment was indeed astute by having one of the greatest debuts in major league history. Using a small, light bat and facing the veteran Gus Weyhing of the Philadelphia Phillies, Clarke proceeded to hit four singles and a triple in five at bats. The rest of the season was not as outstanding, but still, the rookie averaged .274 with 55 runs scored and 48 RBI in 76 games with a last-place team.[22]

During the next five seasons, Clarke came into his own as the starting left fielder of the Colonels and developed a reputation as an excellent hitter, a fast, aggressive base runner, a daring defender, and a fearless competitor who never backed down from a fight. While at Louisville, Clarke hit for a .334 average, reaching base at a .398 clip, and once on base, he became the 19th-century version of Ty Cobb, believing that the base paths belonged to the runner and that the infielder had better beware. As a defender, he was willing to take chances, creating a diving method of snagging the ball that often resulted in spectacular catches. In fact, Clarke devised such a method of fielding to offset his one weakness as an outfielder: going back for a ball. To counter this weakness, Clarke would play a relatively deep left field and allow his speed and agility to make up the difference. And as a competitor, his desire to excel was unsurpassed. This desire was perhaps best attested to by veteran sportswriter Fred Lieb, who said in the obituary on Clarke that he wrote for the August 24, 1960, issue of The Sporting News, “With the possible exception of Cobb and John McGraw, baseball never knew a sturdier competitor than Clarke.”[23]

However, Clarke’s major league career as both a player and a manager might not have blossomed if fate had not entered the picture three more times—each in the form of Barney Dreyfuss. The first instance came about when Clarke joined Louisville. At that time, he was only 21 years of age and got caught up trying to imitate the lifestyles of the veteran players, lifestyles that involved a lot of drinking and womanizing. Clarke pursued these dissolute ways, even though doing so hurt his ability to perform, until one day, Dreyfuss, who was one of the stockholders and the secretary of the Colonels, intervened and, according to Clarke, asked the younger man:

Are you fair with yourself?

… You will live in the major league a few years only if you continue to dim your batting eye and weaken your physical self by carousing around. Then you will go back to the minors and be swallowed up, and you never will have been any one [sic]. It’s up to you. Think it over.[24]

Clarke did think it over, cleaned up his act, and dedicated himself to his profession. This change of attitude was seen immediately during Clarke’s years at Louisville, where he finished in the National League’s top 10 in positive offensive categories 39 times, led in three of them,[25] and had his greatest season in 1897, batting .390, with a .461 on-base average and a .530 slugging percentage, and scoring 122 runs.[26]

The second instance occurred when Dreyfuss recognized Clarke’s potential as a leader and had him named the Louisville manager in June of 1897.[27] Although Clarke was just 24 years old at the time of his promotion, he responded well to the challenge and began to change Louisville from a perennial doormat to a competitive franchise. Also, Clarke’s new position led to his receiving the nickname of “Cap,” because managers in the 1890s were often referred to as captains.

And the third instance happened in late 1899 when Dreyfuss, by then the owner-president of the soon-to-be-extinct Colonels, became partial owner and president of the Pittsburgh Pirates and engineered a trade that sent Clarke and the other good Louisville players to the Steel City franchise. What followed was a 16-year period that would catapult Clarke to the heights of baseball greatness.

After arriving in Pittsburgh, Clarke made the most of the hand that fate had dealt him. From 1900 through 1911, he not only patrolled left field and hit in the upper third of the batting order for the Bucs, usually second or third, but he also managed the Pirates from the field. Then between 1912 and 1915, he benched himself for all but a dozen games and led the team from the dugout. During those 16 seasons, Clarke amassed an enviable record by piloting the Pirates to one World Series championship out of two attempts, four pennants, a remarkable 14 straight first-division finishes, 1,422 wins, and a winning percentage of .595—all of which, with the exception of the one World Series championship, remain Pirate records. Just as impressively, he accomplished these feats while managing against the likes of Ned Hanlon, Frank Selee, John McGraw, Frank Chance, and George Stallings. And this raises the question of what were the secrets of Clarke’s success as a manager.

In a candid interview for an article found in the May 23, 1915, issue of the (Philadelphia) Public Ledger, Clarke said that “[t]he successful manager must, of course, know baseball.”[28] Then, he must have “the shrewdness, cheek, information and money” to get good players.[29] And finally, he had to be able to shape the players “into a big, happy whole, both on and off the field.”[30] These were the traits that Clarke consistently applied throughout his managerial career, with the money usually coming from Barney Dreyfuss. And it was because of the third trait that Clarke got rid of the talented but eccentric Rube Waddell in 1901. It was not that Clarke did not recognize Waddell’s ability. When Clarke chose his major league all-time all-star team, he selected Waddell as his top left-handed pitcher.[31] But Waddell’s antics disturbed the harmony of the Pittsburgh club and Clarke would not put up with such actions. For Clarke, a disruptive force had to go, “no matter how good a ball player [sic] he [was].”[32] Also, partially because of Clarke’s knack for producing good morale among his players, the new American League franchises had a difficult time stealing his men.

However, added to these traits, Clarke had four others that helped push him into the upper echelon of managers. First, he believed in maintaining a positive attitude. He felt that no matter how bleak things may appear, the manager had to display confidence to his players and keep smiling in the face of adversity. Second, he led by example. Clarke did not want a team of rowdies, but he also did not want a team that would be pushed around by the opposition. As player-manager, he showed his players through his own actions that while off the field he expected them to be gentlemen, on the field he expected them to be as combative as he was. Third, Clarke was not afraid to take chances with his managerial moves. Whether it was shifting Claude Ritchey from shortstop to second base, moving Honus Wagner to shortstop, or starting Babe Adams in the first game of the 1909 World Series, Clarke shrewdly gambled and succeeded. And finally, like John McGraw, Clarke would not tolerate mental mistakes and was quick to castigate players who made them.

But Clarke was more than just a successful manager. Between 1900 and 1911, he was a star player as well. It was during those years that Clarke led the National League eight times in positive offensive categories, finished in the league’s top 10 in positive offensive categories 121 times, and hit for the cycle twice.[33] In the 1909 World Series, Clarke’s clutch performances at the plate contributed to each of the Pirate victories. On the base paths, Clarke continued to play in the style that he had developed at Louisville, using his arms and legs to jar balls loose from fielders, breaking up double plays with reckless abandon, and holding his own in fights with Cupid Childs, Fred Tenney, and others. Even while still at the plate, he showed his will to win by trying to hit the catcher with the backswing of his bat or by throwing his bat back at the catcher on a close play at third or home. Also, Clarke excelled defensively, leading outfielders in the National League twice in fielding percentage and once in putouts,[34] finishing in the league’s top five in positive defensive categories for an outfielder 13 times,[35] recording four assists in a game in 1910, and making 10 putouts in a game in 1911.[36]

Off the field, Clarke was a multifaceted individual. He created and held patents for flip-down sunglasses, a sliding pad, an additional rubber strip placed in front of the official pitching rubber to prevent pitchers from catching their spikes when they pivoted, a small equipment bag, and an early mechanical way of handling the tarpaulin;[37] he was an avid hunter and fisherman, a Kansas state champion amateur trap shooter, and an outstanding horseman who could do riding tricks;[38] and he became a highly successful rancher whose wealth was estimated at $1,000,000 in 1917—the equivalent of $90,900,000 in 2013[39]—after oil was discovered on his property the previous year.[40]

Clarke was also a family man. On July 5, 1898, he married the spunky Annette Gray of Chicago, by whom he had two daughters, Helen and Muriel, and with whom he lived for over 62 years,[41] mostly on his Little Pirate Ranch, which ultimately comprised 1,320 acres.[42] And it is interesting to note that among Clarke’s brothers-in-law was the major league pitcher Charles “Chick” Fraser, who had married one of Annette Gray’s sisters.[43]

Because of his desire to spend more time with his family, and because he certainly did not need the money, Clarke wanted to retire from baseball after the Pirates had won the 1909 World Series, but it seems that fate, again in the form of Barney Dreyfuss, persuaded him not to do so. However, after the Bucs finished seventh in 1914 and were on the verge of finishing fifth the following season, Clarke submitted his resignation in early September of 1915, and Dreyfuss reluctantly accepted it. September 23, 1915, was proclaimed Fred Clarke Day in Pittsburgh, and Clarke suited up one more time, playing four innings and going one-for-two against Dick Rudolph of the Boston Braves. For farewell gifts, Clarke received an eight-day clock from his players and a leather binder containing the names of several thousand supporters.

Clarke temporarily left major league baseball once the season was over, but perhaps it was fate disguised yet again as Barney Dreyfuss that brought him back for his last hurrah in 1925 and 1926. This final curtain call came about when Dreyfuss felt that something was missing from his 1925 Pirate team. Between 1921 and 1924, Pittsburgh had fielded competitive teams, but they all lacked the discipline and mental toughness to consistently play well enough to win the pennant. The 1925 team, under manager Bill McKechnie, started slow, but by June 12, it was tied for second, five and a half games behind the first-place Giants and Dreyfuss’ hated nemesis, John McGraw. At this point, Dreyfuss, tired of seeing his teams finish second or third to McGraw’s New Yorkers, invited Clarke to return to Pittsburgh as his personal assistant, head of scouting, and assistant to the manager, a position where Clarke could directly exercise his inspired leadership,[44] though Clarke was initially reluctant to sit on the bench next to McKechnie.[45] It appears that Dreyfuss hoped Fearless Fred would instill in the Bucs the combative spirit necessary for them to go all the way, and he was not disappointed. The Pirates, fired up by Clarke, surged to take over first place on June 29, and then, after remaining there every day except for five, clinched the pennant on September 23, finishing the season with an eight-and-a-half-game lead over the Giants.

Clarke’s never-say-die attitude carried over to the World Series, too. Down three games to one to the defending World Series champion Washington Senators, the Pirates rallied to win three games in a row, clinching the title on a rain-soaked October day at Forbes Field, 9-7.

The players, viewing Clarke as part of the front office and knowing that he was already a millionaire, voted him only a $1000 share of the winner’s pot—the same amount that the two main Pirate scouts received—while voting 22 members of the playing personnel, as well as Bill McKechnie, coach Jack Onslow, and Sam Watters, the club secretary, full shares of $5,332.71 apiece.[46] Some later writers have speculated that this decision was the source or the first sign of animosity between Clarke and certain Pirate players, but such speculation seems to be unfounded and read into the story after the fact. The players may have been greedy and/or they may have felt that Clarke already had enough money, but they were quick to sing his praises, along with those of McKechnie, when Pittsburgh secured the pennant in September,[47] and there were no public objections to Clarke’s staying with the team.

As for the sportswriters, they could not say enough good things about Clarke’s efforts. As early as July 5, Jack Gallagher of the Los Angeles Times wrote:

… McGraw’s old baseball enemy, Fred Clarke, stepped into the picture again as adviser to the Pirate team … and, after that, the baseball world witnessed the boys from Pittsburgh literally smash their way to the top of the parent [league]. …

No one has learned just what prompted Barney Dreyfuss … to bring his former manager back into active service. The logical conclusion is that after the Pirates missed three or four pennants that seemed to be within their grasp, Dreyfuss decided that something was lacking and that Clarke could supply that particular something. He did.[48]

And other such compliments followed,[49] including an article written by Daniel M. Daniel and published in Baseball Magazine[50] that credited Clarke with teaching the Pirates to be confident in themselves, and thus helping them to get over their collective inferiority complex, and with serving as “the spiritual adviser and the father confessor of the players and the strategical aid of McKechnie.”[51]

Sadly, for Clarke, however, what proved so successful during the 1925 season led to his resignation after the following season. At the wish of Barney Dreyfuss, Clarke became the Bucs’ vice president during the 1925-1926 offseason, while remaining as head of scouting and assistant to the manager and agreeing to continue to provide advice from the bench.

But the performance of the 1926 Pirate team was different from that of the 1925 one, though the two teams were comprised of essentially the same players. High expectations by the media and the fans had caused an equally high level of stress, while a variety of injuries and ailments had produced frustration. A prime example of this was Max Carey, the Pirate center fielder and team captain, who after suffering from a respiratory ailment, could not regain the form that had made him one of the stars of the ’25 World Series champions.[52] But Carey was not alone, as key players such as Vic Aldridge, Clyde Barnhart, Johnny Gooch, George Grantham, Ray Kremer, Eddie Moore, Johnny Morrison, Pie Traynor, and Glenn Wright, among others, were also stricken with some mishap or malady at one time or another in spring training or during the course of the season.[53]

By mid-July, tensions became evident when McKechnie fined Eddie Moore and Emil Yde for lackadaisical play in a doubleheader loss against the Giants.[54] Moore was subsequently put on waivers and claimed by Boston,[55] and shortly thereafter, two other players were penalized for their behavior. Vic Aldridge was fined for dressing and leaving the clubhouse without McKechnie’s permission after being removed from the second game of a doubleheader,[56] and Johnny Morrison was suspended for being absent without leave.[57]

It was out of this environment that the notorious ABC Affair arose, a series of events which has been misconstrued or distorted by some later writers and wrongly blamed for being the major, if not the only, cause of the Bucs not repeating as National League champions. The events themselves, so detailed and complex, are examined by Angelo Louisa in his book on the 1926 Pirates.[58] But suffice it to say that the incident started when the three Pittsburgh players with the most seniority on the team, Babe Adams, Carson Bigbee, and Max Carey—hence the acronym “ABC”—approached Bill McKechnie on August 7 and said “that they were planning a meeting of the players on the club to draw up a verbal resolution to keep Clarke off the bench.”[59] The exact reason for the attempted resolution is debatable, but it appeared to have been a knee-jerk reaction to a comment that Clarke had made to McKechnie earlier that day. Despite being in first place at that time, Pittsburgh had dropped a doubleheader to lowly Boston by identical scores of 2-0, and in between the first and second games, Clarke suggested that McKechnie remove the slumping Carey and replace him with anyone else he could find. Carey apparently did not hear the remark, but supposedly his good friend Bigbee did and told him. The two then went to Babe Adams, the oldest player on the club and the leading member in number of years played in a Pirate uniform and asked him for his opinion on the matter. Adams is said to have responded in words that made it clear that there should be only one manager on the team.

This encounter thus began a snowball effect that led to the Pittsburgh players voting by secret ballot to keep Clarke on the bench by an 18-to-6 margin; Clarke wanting immediate action taken against the ABC trio; Adams and Bigbee being unconditionally released; and Carey being put on waivers.[60] As the season progressed, the Pirates continued to battle St. Louis and Cincinnati for the National League pennant, but they eventually finished in third place, four and a half games behind the Cardinals, and Bill McKechnie did not have his contract renewed when it ran out after the season was over.

The matter should have ended there, but on September 30, 1926, Adams, Bigbee, and Carey came forth with a self-serving statement that was published in the Pittsburgh Press, which said, in addition to other things, that dissension on the Pirate team had started shortly after Clarke assumed his duties as assistant to the manager in 1925, that “[p]layers sitting on the bench repeatedly heard Clarke give orders to the batter going up to the plate that would conflict with McKechnie’s signals from the coaching lines,”[61] and that Clarke had bullied the players in August of 1926 into voting to keep him on the bench.[62] Clarke emphatically denied and skillfully countered the accusations in a news conference held that evening, the most detailed version of which was published by the Pittsburgh Post the next morning,[63] but ultimately, he became fed up with the mess and left the Pirate organization, resigning his positions and selling his stock in the Pirates in late October of 1926.[64] To paraphrase Clarke’s quotation from 1911, the ripples of fate brought about by a trifle had led to his departure from major league baseball.

After 1926, the rest of Clarke’s life was spent ranching, being involved in Winfield community activities, pursuing his varied interests, holding leadership positions with the National Baseball Congress,[65] and enjoying time with his family. During those years, it seems that fate continued to intervene in his life as he narrowly escaped serious injury or death in a fishing accident, a hunting mishap, and a furnace explosion. While on a fishing trip to a lake in Minnesota with his wife, Clarke’s boat capsized during a storm, and he and Mrs. Clarke remained in the water for three hours until they were rescued.[66] Then, after returning to Winfield, Clarke was nearly killed in a Dick Cheney-like incident “when the bill of his hunting cap deflected the pellets from a companion’s accidental shot.”[67] And to top things off, following his hunting misadventure, Clarke went home, turned on his gas furnace, and found himself flying across his basement floor. The furnace had exploded, but once again, the old player-manager was able to survive.[68]

However, if fate was the guiding force in Clarke’s life, then it may have been fate that had him die of pneumonia at age 87 on August 14, 1960, and be buried in Saint Mary’s Cemetery in Winfield. Clarke’s honors include, among others, being elected to the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame (1939), the National Baseball Hall of Fame (1945), the Iowa Sports Hall of Fame (1951), and the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame (1963).

Sources

Acocella, Nick, and Donald Dewey. The “All-Stars” All-Star Baseball Book. New York: Avon, 1986.

Adomites, Paul, and Saul Wisnia. Best of Baseball: A Collection of History’s Greatest Players, Teams, Games, Ballparks, and More. Lincolnwood, Illinois: Publications International, Ltd., 1997.

Balinger, Edward F. “Champtown Chatter.” Pittsburgh Post, July 13, 1926.

________. “Champtown Chatter.” Pittsburgh Post, October 23, 1925.

________. “Champtown Chatter.” Pittsburgh Post, September 2, 1926.

________. “Dreyfuss to Act on Clarke’s Resignation Today; May Abolish Vice-Presidential Position on Club.” Pittsburgh Post, October 28, 1926.

________. “Ex-Champtown Chatter.” Pittsburgh Post, September 28, 1926.

________. “Fred Clarke Officially Severed from Pirates, Resignation Accepted.” Pittsburgh Post, October 29, 1926.

________. “Fred Clarke Severs Connection with Pirates.” Pittsburgh Post, October 27, 1926.

“Ball Game of To-Day [sic] Postponed.” Pittsburgh Sun, April 21, 1911.

Barnhart, Clyde. Interview by Eugene Converse Murdock. August 4, 1979. Cleveland Public Library. Cleveland, Ohio.

Barrow, Edward Grant, with James M. Kahn. My Fifty Years in Baseball. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1951.

Baseball Magazine 36, no. 2 (January 1926): 365, caption under photograph.

“Baseball Writers Concede Pirates Slight Advantage in World’s Series.” The Sporting News, October 1, 1925.

Bloss, Bob. Baseball Managers: Stats, Stories, and Strategies. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999.

Bryson, Bill. “Fred Clark [sic], Indestructible.” Baseball Digest, March 1948.

Christian, Ralph. “Edward Grant Barrow: The Des Moines Years.” Paper presented at the Society for American Baseball Research National Convention, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1999.

Christian, Ralph to Angelo Louisa. E-mail message of September 22, 2001. Provided information on Clarke’s amateur baseball career.

“The Clarke Family.” Unpublished typescript compiled from information provided by William Howard Scarff, Fred Clarke’s brother-in-law, and given to Angelo Louisa by Margaret Donahoe Burroughs, Clarke’s granddaughter, 2008.

Clarke, F. C. Diamond Cover. U.S. Patent 983,857. Filed June 7, 1909. Issued February 7, 1911.

________. Sliding Pad for Base Ball [sic] Players, etc. U.S. Patent 1,044,494. Filed May 24, 1911. Issued November 19, 1912.

“Clarke in Baseball Post.” New York Times, January 5, 1937.

“Clarke, Wright Pay Flying Visit Here.” Pittsburgh Post, September 3, 1926.

Cobb, William R., ed. Honus Wagner: On His Life & Baseball. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Sports Media Group, 2006.

Cratty, A. R. “Fred Clarke, the Ex-Manager, Believed to Be Worth One Million Dollars as the Result of Lucky Discoveries in Oil.” Sporting Life, January 13, 1917.

Daniel, Daniel M. “How Fred Clarke Taught the Pirates Confidence.” Baseball Magazine 36, no. 4 (March 1926).

Davis, Ralph S. “All Isn’t So Well in Pirate Menage.” The Sporting News, July 8, 1926.

________. “Bucs Now Bearing More Serious Mien.” The Sporting News, August 5, 1926.

________. “Fate of Pirates in Hands of Pitchers.” The Sporting News, June 24, 1926.

________. “M’Kechnie Wields an Iron Fist to Restore Champions to Order.” The Sporting News, July 29, 1926.

________. “M’Kechnie’s Luck Is No Luck at All.” The Sporting News, July 15, 1926.

________. “Pirate Fans Close the ‘Alibi Season.’” The Sporting News, August 12, 1926.

________. “Pirate-Giant Trade? Never, So They Say.” The Sporting News, June 3, 1926.

________. “Secret of Pirate Shakeup Revealed.” Pittsburgh Press, September 30, 1926.

________. “They’ll Be Careful Now, If Not Serious.” The Sporting News, July 22, 1926.

DeValeria, Dennis, and Jeanne Burke DeValeria. Honus Wagner: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995.

Doyle, Charles J. “Cuyler Hits Homer with Bases Full; Score, 15-2.” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, March 24, 1926.

Eckhouse, Morris, and Carl Mastrocola. This Date in Pittsburgh Pirates History. New York: Stein and Day, 1980.

1880 United States Federal Census.

1870 United States Federal Census.

Finoli, David, and Bill Ranier. The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing L.L.C., 2003.

Fred Clarke File. Cowley County Historical Society Museum. Winfield, Kansas.

Fred Clarke File. Madison County Historical Complex. Winterset, Iowa.

Fred Clarke Player File. National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. Cooperstown, New York.

“Fred Clarke Returns to Corsairs in Official Capacity.” Pittsburgh Post, June 13, 1925.

“Fred Clarke Stays as Sandlot Leagues’ Head.” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 27, 1955.

“Fred Clarke: The Baseball Capitalist.” New York Herald, March 5, 1911.

“Fred Clarke to Head New Baseball Veterans’ Group.” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 17, 1944.

“Fred C. Clarke Claimed by Death.” Winfield Daily Courier, August 15, 1960.

Frommer, Harvey. Baseball’s Greatest Managers. New York: Franklin Watts, 1985.

Gallagher, Jack. “Scared of the Pirates.” Los Angeles Times, July 5, 1925.

Gillette, Gary, and Pete Palmer, eds. The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. 5th ed. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2008.

Goewey, Ed A. “The Old Fan Says.” Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, August 6, 1914.

Gould, Alan. “Young and Handley 2 Reasons for Bucs’ Rise.” Washington Post, July 14, 1938.

Hageman, William. Honus: The Life and Times of a Baseball Hero. Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1996.

“Heydler’s Recommendation to Three Players for Other Jobs.” Pittsburgh Post, August 18, 1926.

Hittner, Arthur D. Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball’s “Flying Dutchman.” Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1996.

Hoie, Bob, and Carlos Bauer, comps. The Historical Register: The Complete Major & Minor League Record of Baseball’s Greatest Players. San Diego: Baseball Press Books, 1998.

James, Bill. The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers from 1870 to Today. New York: Scribner, 1997.

James, Bill, John Dewan, Neil Munro, and Don Zminda, eds. STATS All-Time Baseball Sourcebook. Skokie, Illinois: STATS Publishing, 1998.

________, eds. STATS All-Time Major League Handbook. Skokie, Illinois: STATS Publishing, 1998.

King, Joe. “‘The Wonder Man’ of Pittsburgh.” The Sporting News, March 28, 1951.

Koppett, Leonard. The Man in the Dugout: Baseball’s Top Managers and How They Got That Way. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1993.

Lewis, H. Perry. “‘Smile! Smile! No Matter How Things Break,’ Clarke’s Motto.” [Philadelphia] Public Ledger, May 23, 1915.

Lieb, Frederick G. “Fred Clarke.” Baseball Magazine 4, no. 4 (February 1910).

________. “Oilman Clarke Drills into Diamond Memories.” The Sporting News, January 17, 1946.

________. “Pittsburgh Mourns Early-Star Fred Clarke.” The Sporting News, August 24, 1960.

________. The Pittsburgh Pirates. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948. Reprint, Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003.

Louisa, Angelo J. The Pirates Unraveled: Pittsburgh’s 1926 Season. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2015.

McGrane, Bert. “Anson, Clarke, Faber, Feller.” Des Moines Register, April 15, 1951, www.desmoinesregister.com (accessed on January 30, 2007).

Miller, Clarence W. “Fred Clarke–Ball Player [sic], Ranchman–Kansan.” Kansas Magazine, November 1909.

“Moore-Yde Fined.” Pittsburgh Post, July 15, 1926.

“Morrison Handed Suspension by Bucs.” Pittsburgh Post, July 25, 1926.

Murdock, Eugene. Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920-1940. Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Publishing, 1991.

“Nats’ Twirler Fans Ten Bucs in Winning First Contest.” The Sporting News, October 15, 1925.

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th-Century Major League Baseball. New York: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

1940 United States Federal Census.

1900 United States Federal Census.

1910 United States Federal Census.

“Once Grocery Clerk.” Washington Post, July 30, 1911.

Phelps, Frank V. “Fred Clifford Clarke.” In Baseball’s First Stars, edited by Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996.

Pietrusza, David, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, eds. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Kingston, New York: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000.

“Pirates Clinch Flag; Beat the Phils, 2-1.” New York Times, September 24, 1925.

“Pirates Have Upset the Dope in National League Race.” Washington Post, July 5, 1925.

Pope, Edwin. Baseball’s Greatest Managers. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1960.

Porter, David L. “Fred Clifford ‘Cap’ Clarke.” In Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball, edited by David L. Porter. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Inc., 1987.

Register of Deeds, Cowley County Courthouse, Winfield, Kansas.

Reichler, Joseph L. The Great All-Time Baseball Record Book. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1981.

Reiter, Beverly. “Hap Dumont, the National Baseball Congress and the Fred Clarke Connection.” Unpublished paper, 1989.

Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. New enlarged ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1984.

“Six Countries to Compete in Semi-Pro [sic] Meet.” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 30, 1939.

Stein, Fred. And the Skipper Bats Cleanup: A History of the Baseball Player-Manager, with 42 Biographies of Men Who Filled the Dual Role. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2002.

“Sun Glasses.” Sporting Life, February 10, 1912.

“They Say Two Heads Are Better Than One.” The Sporting News, October 22, 1925.

“Vic Is Fined, and Johnny Ordered to Rejoin Club.” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 23, 1926.

Welch, Judy. “Cowley County’s Fred Clarke Brought Fame, Glory to Pittsburgh Pirates.” Arkansas City (Kan.) Traveler, November 8, 1976.

Welsh, Regis M. “Clarke Demands Disciplinary Action Following Expulsion Request.” Pittsburgh Post, August 13, 1926.

________. “Clarke Denies Statements of Discharged Pirates.” Pittsburgh Post, October 1, 1926.

Wollen, Lou. “M’Kechnie Calls Off Pirate Game Scheduled Today.” Pittsburgh Press, March 24, 1926.

www.baseball-almanac.com

Notes

[1] The American Heritage College Dictionary, 4th ed., 2004.

[2] “Fred Clarke: The Baseball Capitalist,” New York Herald, March 5, 1911, Magazine Section, 7.

[3] Although only 10 of Clarke’s sisters and brothers can be found in the 1870 and 1880 United States Federal Census records, which, when combined, show Clarke to be the ninth of 11 children, six girls and five boys, Fred Lieb was correct when he wrote that Clarke was “one of twelve children, having seven sisters and four brothers.” The Clarke family papers list William and Lucy Clarke’s children in order of birth as Anna, Edgar, William, Hattie, Charles, Mattie, Mary, Luttie, Fred, Mabel, Joshua, and Bessie, with Bessie being born in 1881 and, thus, not being counted in the 1880 Census. See 1870 United States Federal Census; 1880 United States Federal Census; Frederick G. Lieb, “Fred Clarke,” Baseball Magazine 4, no. 4 (February 1910): 47; and “The Clarke Family,” unpublished typescript compiled from information provided by William Howard Scarff, Fred Clarke’s brother-in-law, and given to Angelo Louisa by Margaret Donahoe Burroughs, Clarke’s granddaughter, 2008.

[4] David L. Porter, “Fred Clifford ‘Cap’ Clarke,” in Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball, edited by David L. Porter (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Inc., 1987), 94; John Pletchette, “Major League Baseball Hall-of-Famer Born Here” and “Fred Clifford Clarke, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer,” an article and a time line, Fred Clarke File, Madison County Historical Complex, Winterset, Iowa; 1870 United States Federal Census; and 1880 United States Federal Census. Both the 1870 and 1880 United States Federal Census records spell the last name of Clarke’s parents as “Clark,” but a deed found in the office of the Register of Deeds at the Cowley County Courthouse in Winfield, Kansas, spells the name as “Clarke.” Cf. 1870 United States Federal Census; 1880 United States Federal Census; and Register of Deeds, Cowley County Courthouse, Winfield, Kansas, Book E, 356.

[5] Joshua Baldwin “Pepper” Clarke lived from March 8, 1879, until July 2, 1962. And like his brother, Fred, he was primarily a left fielder who batted left-handed and threw right-handed. But unlike his brother, he was no star ballplayer, appearing in only 223 major league games and finishing with a .239 career batting average. “Josh Clarke,” www.baseball-reference.com (accessed on May 5, 2015).

[6] Clarence W. Miller and Porter have the family moving to Kansas when Fred was two, which would have been sometime between October 3, 1874, and October 3, 1875. Frank Phelps and Pletchette have the date set as 1874, but William Clarke bought approximately 160 acres of land in Cowley County, Kansas, on May 13, 1874, and in all likelihood, moved his family during the spring and/or summer of 1874–prior to Fred turning two–or during the spring and/or summer of 1875. Cf. Clarence W. Miller, “Fred Clarke–Ball Player [sic], Ranchman–Kansan,” Kansas Magazine, November 1909, 46; Porter, 94; Frank V. Phelps, “Fred Clifford Clarke” in Baseball’s First Stars, edited by Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996), 29; Pletchette, “Fred Clifford Clarke, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer,” 1; and Register of Deeds, Cowley County Courthouse, Winfield, Kansas, Book E, 356.

[7] Most sources that refer to William Clarke say that he was a farmer, but in the 1870 and 1880 United States Federal Census records, Clarke listed his occupation as a blacksmith. 1870 United States Federal Census and 1880 United States Federal Census.

[8] Miller, 46; Phelps, 29; and Pletchette, “Fred Clifford Clarke, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer,” 1.

[9] Miller, 46, though the 1880 United States Federal Census records do not show the young Fred being in school, like some of his siblings. However, Clarke would later say that he received an eighth-grade education. Cf. 1880 United States Federal Census and 1940 United States Federal Census.

[10] Miller has the Clarke family returning to Iowa in 1880. Porter says that the family went back to Iowa five years after Fred was two, implying either 1879 or 1880. And Phelps and Pletchette have the date set as 1879. But the 1880 United States Federal Census records show the Clarkes living in Kansas as of June 21, 1880. Cf. Miller, 46; Porter, 94; Phelps, 29; Pletchette, “Fred Clifford Clarke, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer,” 1; and 1880 United States Federal Census.

[11] Porter, 94, though Angelo Louisa did not find any evidence of the Dickenson public schools ever being in the Des Moines area.

[12] Pletchette, “Fred Clifford Clarke, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer,” 1.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Once Grocery Clerk,” Washington Post, July 30, 1911, S4; Ralph Christian, “Edward Grant Barrow: The Des Moines Years” (paper presented at the Society for American Baseball Research National Convention, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1999), 4; and Ralph Christian to Angelo Louisa, e-mail message of September 22, 2001. Ed Barrow later claimed that Clarke had played for the Des Moines Stars, but Ralph Christian has found no newspaper evidence to corroborate Barrow’s claim. The biggest difficulty, according to Christian, is “the lack of published box scores for both [the Mascots and the Stars].” Cf. Edward Grant Barrow with James M. Kahn, My Fifty Years in Baseball (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1951), 16, and Ralph Christian to Angelo Louisa, e-mail message of September 22, 2001.

[15] Phelps, 29, and Pletchette, “Fred Clifford Clarke, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer,” 1.

[16] Phelps, 29; Pletchette, “Fred Clifford Clarke, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer,” 1; and Bob Hoie and Carlos Bauer, comps., The Historical Register: The Complete Major & Minor League Record of Baseball’s Greatest Players (San Diego: Baseball Press Books, 1998), 56.

[17] Cf. Lieb, “Fred Clarke,” 47; “Fred Clarke: The Baseball Capitalist,” Magazine Section, 7; “Once Grocery Clerk,” S4; Frederick G. Lieb, “Oilman Clarke Drills into Diamond Memories,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1946, 13; and Bill Bryson, “Fred Clark [sic], Indestructible,” Baseball Digest, March 1948, 46. Ed Barrow had his own version of how Clarke began playing professional baseball, but it lacked any twist of fate. See Barrow, 16.

[18] Hoie and Bauer, 56.

[19] Lieb, “Oilman Clarke Drills into Diamond Memories,” 13.

[20] The official name of this section is the Cherokee Outlet, an area in northern Oklahoma that was made available for white settlement via a land rush on September 16, 1893.

[21] Phelps, 29. There are various versions of how Louisville acquired Clarke, but Phelps’ account is the most plausible.

[22] “Fred Clarke,” www.baseball-reference.com (accessed on May 5, 2015).

[23] Frederick G. Lieb, “Pittsburgh Mourns Early-Star Fred Clarke,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1960, 13.

[24] “Fred Clarke: The Baseball Capitalist,” Magazine Section, 7.

[25] Not including games played, plate appearances, and at bats, in which he was in the top 10 once, twice, and three times, respectively. “Fred Clarke,” www.baseball-reference.com (accessed on May 5, 2015).

[26] Ibid. (accessed on May 5, 2015).

[27] The Louisville directors, of which Dreyfuss was a member, made the official decision, but it appears that Dreyfuss was the driving force behind that decision.

[28] H. Perry Lewis, “‘Smile! Smile! No Matter How Things Break,’ Clarke’s Motto,” [Philadelphia] Public Ledger, May 23, 1915, 6, copy found in Fred Clarke Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Clarke’s complete all-time all-star team, which was sent to Nicholas Acocella at some undisclosed date, consisted of Hal Chase at first base, Eddie Collins at second, Honus Wagner at shortstop, Jimmy Collins at third, Tris Speaker, Ty Cobb, and Babe Ruth in the outfield, Johnny Kling behind the plate, and Christy Mathewson (his right-hander) and Rube Waddell on the mound. Clarke also sent a letter to Ernest J. Lanigan on January 14, 1947, in which he included an all-star team of only men whom he had played with or against. The members of this team were Frank Chance at first base, Nap Lajoie at second, Honus Wagner at shortstop, Jimmy Collins at third, Ed Delahanty in left field, Ty Cobb in center field, Hugh Duffy in right field, Johnny Kling and Roger Bresnahan as catchers, Tommy Leach as the utility man, and a pitching staff of Grover Cleveland Alexander, Christy Mathewson, Mordecai Brown, and Rube Waddell. In addition, in 1951, Clarke told Joe King of the New York World-Telegram and Sun that his all-star team of “only men [he] had a chance to follow through a season” was comprised of Bill Terry at first base, Nap Lajoie at second, Honus Wagner at shortstop, Jimmy Collins at third, Tris Speaker, Hugh Duffy, and Ty Cobb in the outfield, Johnny Kling as catcher, Christy Mathewson as his right-handed pitcher, and, once again, Rube Waddell as his southpaw. Nick Acocella and Donald Dewey, The “All-Stars” All-Star Baseball Book (New York: Avon, 1986), 38; a letter from Fred C. Clarke to Ernest J. Lanigan, January 14, 1947, Fred Clarke Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York; and Joe King, “‘The Wonder Man’ of Pittsburgh,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1951, 21-22.

[32] Lewis, 6.

[33] Not including games played and plate appearances, in which he was in the top 10 twice for both. “Fred Clarke,” www.baseball-reference.com (accessed on May 2, 2015), and Joseph L. Reichler, The Great All-Time Baseball Record Book (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1981), 112.

[34] “Fred Clarke,” www.baseball-reference.com (accessed on May 5, 2015). Clarke’s 362 putouts and .987 fielding percentage in 1909 led outfielders in both major leagues. Also that season, he came in second in range factor per game for major league outfielders.

[35] “Fred Clarke,” www.baseball-reference.com (accessed on May 5, 2015).

[36] Reichler, 269, and Morris Eckhouse and Carl Mastrocola, This Date in Pittsburgh Pirates History (New York: Stein and Day, 1980), 25, 60.

[37] “Sun Glasses,” Sporting Life, February 10, 1912, 14; Ed A. Goewey, “The Old Fan Says,” Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, August 6, 1914, 134; F. C. Clarke, Sliding Pad for Base Ball [sic] Players, etc., U.S. Patent 1,044,494, filed May 24, 1911, issued November 19, 1912; “Ball Game of To-Day [sic] Postponed,” Pittsburgh Sun, April 21, 1911, 13; F. C. Clarke, Diamond Cover, U.S. Patent 983,857, filed June 7, 1909, issued February 7, 1911; Judy Welch, “Cowley County’s Fred Clarke Brought Fame, Glory to Pittsburgh Pirates,” Arkansas City (Kan.) Traveler, November 8, 1976, 10; and Dennis DeValeria and Jeanne Burke DeValeria, Honus Wagner: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1995), 200-201.

[38] Bryson, 45; Welch, 10; “Fred Clarke: The Baseball Capitalist,” Magazine Section, 7; and DeValeria and DeValeria, 174.

[39] Based on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. www.measuringworth.com (accessed on November 28, 2014).

[40] A. R. Cratty, “Fred Clarke, the Ex-Manager, Believed to Be Worth One Million Dollars as the Result of Lucky Discoveries in Oil,” Sporting Life, January 13, 1917, 4, and Alan Gould, “Young and Handley 2 Reasons for Bucs’ Rise,” Washington Post, July 14, 1938, 19.

[41] Miller, 49; “Mrs. Clarke Dies at Newkirk,” an undated article from an unknown source, Fred Clarke File, Cowley County Historical Society Museum, Winfield, Kansas; Porter, 94, though Porter incorrectly states that Clarke was married in October; and Phelps, 30. Annette Gray was born on February 10, 1879, in Chicago and died on November 14, 1961, at the home of her daughter, Muriel, in Newkirk, Oklahoma.

[42] “Fred C. Clarke Claimed by Death,” Winfield Daily Courier, August 15, 1960, 2.

[43] DeValeria and DeValeria, 58. Fraser pitched in the majors for 14 seasons, including two and most of a third with Louisville when Clarke played there.

[44] Although Clarke was referred to by different titles by various authors, these were his official positions. “Fred Clarke Returns to Corsairs in Official Capacity,” Pittsburgh Post, June 13, 1925, 9.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Edward F. Balinger, “Champtown Chatter,” Pittsburgh Post, October 23, 1925, 12.

[47] “Pirates Clinch Flag; Beat the Phils, 2-1,” New York Times, September 24, 1925, 20.

[48] Jack Gallagher, “Scared of the Pirates,” Los Angeles Times, July 5, 1925, A6. Also, see “Pirates Have Upset the Dope in National League Race,” Washington Post, July 5, 1925, 21.

[49] For a few examples, see “Baseball Writers Concede Pirates Slight Advantage in World’s Series,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1925, 3; “Nats’ Twirler Fans Ten Bucs in Winning First Contest,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1925, 3; and “They Say Two Heads Are Better Than One,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1925, 3.

[50] Daniel M. Daniel, “How Fred Clarke Taught the Pirates Confidence,” Baseball Magazine 36, no. 4 (March 1926): 443-444.

[51] Ibid., 444.

[52] Ralph S. Davis, “M’Kechnie’s Luck Is No Luck at All,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1926, 3. It is possible that the problem was caused by an injury that Carey sustained during the fifth game of the 1925 World Series when he collided with Bucky Harris and tore loose several ligaments from his ribs. See the caption under the photograph found in Baseball Magazine 36, no. 2 (January 1926): 365.

[53] For some examples of Pirate injuries, see Charles J. Doyle, “Cuyler Hits Homer with Bases Full; Score, 15-2,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, March 24, 1926, 11; Lou Wollen, “M’Kechnie Calls Off Pirate Game Scheduled Today,” Pittsburgh Press, March 24, 1926, 28; Ralph S. Davis, “Pirate-Giant Trade? Never, So They Say,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1926, 1; Ralph S. Davis, “Fate of Pirates in Hands of Pitchers,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1926, 3; Ralph S. Davis, “All Isn’t So Well in Pirate Menage,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1926, 1; Edward F. Balinger, “Champtown Chatter,” Pittsburgh Post, July 13, 1926, 11, 14; Davis, “M’Kechnie’s Luck Is No Luck at All,” 3; Ralph S. Davis, “Bucs Now Bearing More Serious Mien,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1926, 1; Ralph S. Davis, “Pirate Fans Close the ‘Alibi Season,’” The Sporting News, August 12, 1926, 1; Edward F. Balinger, “Champtown Chatter,” Pittsburgh Post, September 2, 1926, 13; “Clarke, Wright Pay Flying Visit Here,” Pittsburgh Post, September 3, 1926, 11; Edward F. Balinger, “Ex-Champtown Chatter,” Pittsburgh Post, September 28, 1926, 15; Clyde Barnhart, interview by Eugene Converse Murdock, August 4, 1979, Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland, Ohio; and Eugene Murdock, Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920-1940 (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Publishing, 1991), 178.

[54] “Moore-Yde Fined,” Pittsburgh Post, July 15, 1926, 11, and Ralph S. Davis, “They’ll Be Careful Now, If Not Serious,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1926, 1.

[55] Ralph S. Davis, “M’Kechnie Wields an Iron Fist to Restore Champions to Order,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1926, 1.

[56] “Vic Is Fined, and Johnny Ordered to Rejoin Club,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 23, 1926, 11.

[57] “Morrison Handed Suspension by Bucs,” Pittsburgh Post, July 25, 1926, sec. 3, 3.

[58] Angelo J. Louisa, The Pirates Unraveled: Pittsburgh’s 1926 Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2015).

[59] Regis M. Welsh, “Clarke Demands Disciplinary Action Following Expulsion Request,” Pittsburgh Post, August 13, 1926, 12.

[60] On August 17, 1926, John Heydler, the president of the National League, met with all the parties involved–Adams, Bigbee, Carey, Clarke, McKechnie, and Sam Dreyfuss (Barney’s son), who, with Clarke, was running the Pirate organization while Barney Dreyfuss was in Europe–as well as with Sam Watters, the club secretary. After listening to each participant’s comments about the matter, Heydler issued a lengthy statement in which he exonerated the players of disloyalty, insubordination, and maliciousness but charged them with having “mistaken zeal” and criticized them for their mishandling of the situation. Heydler went further in his statement to defend Clarke and to uphold the decision of the Pittsburgh club to get rid of the ABC trio. For Heydler’s complete statement, see “Heydler’s Recommendation to Three Players for Other Jobs,” Pittsburgh Post, August 18, 1926, 11.

[61] Ralph S. Davis, “Secret of Pirate Shakeup Revealed,” Pittsburgh Press, September 30, 1926, 1.

[62] For the complete statement, see ibid., 1-2, 6.

[63] Regis M. Welsh, “Clarke Denies Statements of Discharged Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post, October 1, 1926, 1, 14.

[64] Edward F. Balinger, “Fred Clarke Severs Connection with Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post, October 27, 1926, 1, 15; Edward F. Balinger, “Dreyfuss to Act on Clarke’s Resignation Today; May Abolish Vice-Presidential Position on Club,” Pittsburgh Post, October 28, 1926, 13, 16; and Edward F. Balinger, “Fred Clarke Officially Severed from Pirates, Resignation Accepted,” Pittsburgh Post, October 29, 1926, 11.

[65] See “Clarke in Baseball Post,” New York Times, January 5, 1937, 26; “Clarke Heads Board of Semi-Pro [sic] Congress,” an undated article from an unknown source, Fred Clarke Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York; “Six Countries to Compete in Semi-Pro [sic] Meet,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 30, 1939, 15; “Fred Clarke to Head New Baseball Veterans’ Group,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 17, 1944, A2; “Fred Clarke Stays as Sandlot Leagues’ Head,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 27, 1955, A7; “Fred Clarke to Be Feted at Non-Pro [sic] Baseball Meet,” an article dated August 3, 1959, from an unknown source, Fred Clarke Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York; and “Bucs to Honor Clarke, 86,” an undated article from an unknown source, Fred Clarke Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

[66] Bryson, 45.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid.

Full Name

Fred Clifford Clarke

Born

October 3, 1872 at Winterset, IA (USA)

Died

August 14, 1960 at Winfield, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.