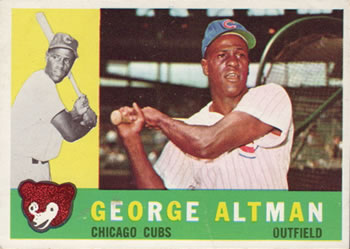

George Altman

As the title of his 2013 autobiography showed, George Altman’s baseball journey took him from the Negro Leagues (1955) to the majors (1959-67) and beyond (Japan, 1968-75). The slugging 6-foot-4 outfielder, who also played first base from time to time, hit 101 home runs in the majors. He was a National League All-Star in 1961 and 1962, but a string of nagging injuries prevented him from achieving stardom in the U.S. over a longer period. However, he went on to hit 205 homers in Japanese ball, in a career that ended when he was 42 years old.

As the title of his 2013 autobiography showed, George Altman’s baseball journey took him from the Negro Leagues (1955) to the majors (1959-67) and beyond (Japan, 1968-75). The slugging 6-foot-4 outfielder, who also played first base from time to time, hit 101 home runs in the majors. He was a National League All-Star in 1961 and 1962, but a string of nagging injuries prevented him from achieving stardom in the U.S. over a longer period. However, he went on to hit 205 homers in Japanese ball, in a career that ended when he was 42 years old.

George Lee Altman was born on March 20, 1933, in Goldsboro, North Carolina. This small city lies in the east-central part of the Tar Heel State, southeast of the Raleigh-Durham metro area. During Altman’s youth, the local economy relied most heavily on farming – especially of tobacco – though there was some manufacturing in the area. All of the schools were segregated and the town was divided.1

Altman’s father, Willie, was a tenant farmer and later an auto mechanic. His mother, Clara (née Langston), was a homemaker. George was their only child. His mother died when he was four years old – he never really knew her – and so the boy went to live with his father’s sister for about a year. Willie then remarried, and George moved back in with his father and stepmother.2

Altman’s father did not care about sports at all. George, however, “lived and breathed sports as a little boy – he cried when he was told to stay home from a game because of bad weather.”3 He later speculated that his interest in athletics arose from being an only child; since he had no help when he got into fights with other boys, his way to get back at them came through games.4

Altman ran well, and he had a jesting theory about how he developed his fast feet: from competing in youth recreational programs in Goldsboro, in a rival team’s gym. “After the game, you had to move on home. They [other players] get very territorial after a while. And that’s how I think I got my speed.”5

Altman attended Dillard High School in Goldsboro, starting in 1947. He played four years of baseball there, as well as basketball and football. He then attended Tennessee A&I State University, a historically black institution in Nashville that was renamed Tennessee State University in 1968. Altman had worked as a laborer during his teens and didn’t like it. He called the benefits of a college education “immeasurable.”6

Tennessee A&I did not have a baseball team in either Altman’s freshman or sophomore year; it started when he was a junior. The college was actually interested in Altman for basketball, in which his height was an asset. He played under the pioneering coach John McLendon, who later became the first African-American head coach in any professional sport.7 Altman described McLendon as a demanding technician who kept his players in top physical condition with constant running and drilled them in the finer points of the game.8

Altman jammed a knee while playing basketball, however, and it affected his jumping a bit. After four years of college hoops, the wear on his knees increased his doubts about whether he had a professional future on the hardwood. In addition, even then he wasn’t big enough to be a forward in the NBA – he would have had to become a guard. He was not drafted.9

Therefore, Altman thought about coaching. After getting his degree in physical education, he received an offer to become the basketball coach at Lemoyne College in Memphis. Although he was only 22, he was confident that he could do it.10

However, the business manager of athletics at Tennessee A&I, J.C. Kincaide, was a booking agent in his territory for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League. He tipped them off to Altman, who worked out with the team when it visited Indianapolis.11 The Monarchs’ interest led Altman to change his career plans; he joined the team in 1955.

The Monarchs were managed by the universally beloved baseball legend Buck O’Neil. “I had been an outfielder all of the way,” Altman said, “but Buck taught me how to play first base and I played first base for the Monarchs that summer. He taught me all of the moves around the bag when receiving the throws from the infielders.”12

Altman played in Kansas City just three months, though, before signing with the Chicago Cubs. Nonetheless, he enjoyed the experience greatly. Reminiscing in 2016, he said, “What I liked about the Negro Leagues was all the history. I heard about all these guys, and I just liked how colorful it was when they played. They had colorful nicknames – Double Duty Radcliffe, Smokey Joe Williams, Boojum Wilson.”13

Signing with the Cubs “was all because of Buck O’Neil. The Cubs signed me, Lou Johnson, and J.C. Hartman all together on Buck’s say-so. All three of us signed as amateur free agents before the end of 1955 and the Cubs paid Kansas City something like $11,000.”14

During Altman’s first season in the minors, 1956, he played for the Burlington (Iowa) Bees in the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League (Class B). He hit .263 with 16 homers and 67 RBIs in 121 games. The young black man suffered some racial epithets from opponents, and he wasn’t especially comfortable with his Southern white teammates, even though they did not insult him.15

After the season ended, Altman received a draft notice from the U.S. Army. “I pretty much went straight from Burlington into the Army and was sent to Fort Carson, Colorado,” he recalled.16 While he was in the service, Altman continued to play baseball (as well as basketball). “The Army experience was huge,” he said, “because of the way I played with other guys who I knew were ahead of me in the minors, or in the majors. We played against some major league players in the All-Army Championships tournament.”17

Fort Carson won the All-Army title. In the final game against Fort Dix, Altman had a key hit in the 5-1 victory: a two-run inside-the-park homer. Another member of the Mountaineers was Willie Kirkland, who played in the majors from 1958 through 1966 and in Japan from 1968 through 1973.18

When Altman returned to the minors in 1958, he was promoted to Class A. With Pueblo (Colorado) of the Western League, he posted a strong batting line of .325-14-78 in 89 games. As evidence of his speed, he also hit 11 triples. That September, The Sporting News mentioned that Cubs farm director Charlie Grimm was “quite high on the husky outfielder.”19

Soon thereafter, Altman went to Panama to play winter ball. He was a member of the Marlboro Smokers. Statistics from very near the end of the season show that in 139 at-bats, he hit .288 with seven homers (just one behind the league leaders) and 22 RBIs.20 Watching him there, on the recommendation of Pueblo manager Ray Mueller, was the Cubs’ head scout, Ray Hayworth. Hayworth reported to the front office that Altman was ready for the majors – defensively at least.21

Altman vaulted directly to the majors in 1959, thanks to his “exceptionally impressive” performance in spring training – though it was mainly his batting that opened eyes. It was thought that he would need at least one year in Triple-A, but instead the Cubs traded Chuck Tanner and made room for their prospect.22 When it became official that Altman had won a roster spot, Cubs vice-president John Holland said, “The thing that I like about him is that he very seldom swings at bad pitches. We think he is going to make it.”23

Altman’s teammate, the great Ernie Banks, seconded the opinion that the rookie had excellent knowledge of the strike zone. Two more of the greatest hitters in baseball history also observed Altman firsthand that spring. Rogers Hornsby, then a coach with the Cubs, said that Altman couldn’t miss. Ty Cobb said, “George isn’t a sucker for any kind of pitch.”24

Altman also got married for the first time in March 1959, to Raquel DeCastro. The wedding took place in Pueblo, where they had met. George and Rachel (as she was more commonly known) were married for 13 years and had two children: Laura and George Jr.25 Rachel was a fair-skinned Hispanic woman who looked Caucasian, and as Altman observed, “We heard about that a lot in the United States.”26

As Chicago’s primary starting center fielder in 1959, Altman hit .245-12-47 in 135 games. He was benched for a time in midseason, but his hitting picked up sharply after he returned to the lineup in mid-August. Of his 12 homers that season, seven came after August 13, including four in three days from September 21-23. Most notable was a game-ending blow at Wrigley Field on September 22, a two-out, two-run shot off Sam Jones that damaged the San Francisco Giants’ pennant hopes. His fielding was also well regarded.

Altman also handled the demanding mental aspects of life in the majors well. Manager Bob Scheffing said, “He not only is eager to learn, but has the intelligence to absorb instruction.”27 Altman got a lot of help in adjusting from his roommate on the road, Cuban second baseman Tony Taylor.28

Scheffing wanted Altman to go to winter ball again, with an express desire that it be in the best competition possible – “a league with good pitching, a lot of breaking stuff, like screwballs, sliders and curves.”29 At the time, the top winter league was Cuba’s. Altman joined the Cienfuegos Elefantes. He played first base, since the team already had a fine regular center fielder in Tony González. Though Altman hit just .251 in 219 at-bats, he belted 14 homers, which led the club and was just one behind Pancho Herrera for the league lead.30

Cienfuegos won the Cuban pennant that season and thus went on to the Caribbean Series, which pitted the champions of the region’s winter leagues against each other in a round-robin tournament. Cuba won all six of its games. Jorge Figueredo later wrote, “The greatest team ever in Cuban baseball? Maybe it was this Cienfuegos edition of 1959-60.”31

During that Caribbean Series, Altman went 7-for-16 (.438), tied with Panama’s Eddie Napoleon, but neither man had enough at-bats to qualify for the tournament’s best average, so that honor went to Tommy Davis (9-for-22, .409).32 That was the last time the Caribbean Series would be held, however, until it was revived in 1970.

Altman also enjoyed life in Cuba; he had always been interested in languages and picked up some Spanish. There was a downside to that winter season, though, that became visible over time. He noted, “My injury problems started with a sprained ankle in Cuba. It also became a knee problem. I think I started having knee pain because I was favoring my leg because of the sprained ankle.” He reinjured the ankle during the Caribbean Series.33

Also, while the 1959-60 Cuban season was in progress, Chicago obtained veteran center fielder Richie Ashburn in a trade with the Philadelphia Phillies. As a result, with the Cubs in 1960, Altman rotated among the three outfield spots and first base. He started no more than 25 games at any position. He hit .266-13-51 in 119 games. Various ailments hampered him throughout that year – he had come home from Cuba with mononucleosis, which took him a long time to get over, and a kidney infection. Making matters worse, he injured his ankle a third time.34

However, the best two seasons of Altman’s big-league career then followed. He became the Cubs’ regular right fielder in 1961 and hit .303-27-96, with a league-leading 12 triples. He had a noteworthy moment in the first of 1961’s two All-Star games. At Candlestick Park in San Francisco, pinch-hitting for Mike McCormick to lead off the eighth inning, he homered off Mike Fornieles of the Red Sox. Having known Fornieles from Cuba, he looked for a curveball, and got all of it on the first pitch.35 It gave the NL a 3-1 lead, and the run proved valuable because the AL tied it in the ninth. The senior circuit won in 10 innings, 5-4. Altman called it one of his two greatest days in the majors. 36

The other of his greatest days came less than a month later. On August 4 at the Los Angeles Coliseum, Altman hit two home runs off Sandy Koufax. Only two other players went deep off the great lefty twice in one game, and they were both righty batters: Ernie Banks (June 9, 1963) and Felipe Alou (July 9, 1966).

The early 1960s were a dismal period for the Cubs. The symbol of the times was the odd experiment that owner Philip Wrigley launched in 1961: the system of rotating managers called “The College of Coaches.” Altman said, “The whole College of Coaches thing was just peculiar. You didn’t know what a manager might do on a given day, what he would say.”37

Altman repeated as an All-Star in 1962 (.318-22-74), even though he suffered a sprained wrist in June that hampered his power production.38 Again the Cubs finished deep in the second division. A bright spot that year, however, was the addition of Buck O’Neil to the coaching staff (though O’Neil was denied his rightful opportunity to be one of the rotating skippers). “He was inspirational to us, just by his presence,” Altman said. “He was also a cheerleader in a fun kind of way.”39

Despite Altman’s strong performance, shortly after the season ended, Chicago traded him, along with pitcher Don Cardwell and catcher Moe Thacker, to the St. Louis Cardinals. In return the Cubs got pitchers Larry Jackson and Lindy McDaniel, plus catcher Jimmie Schaffer. The Cardinals had been interested in Altman for more than a year, and the 310-foot fence in right field in old Busch Stadium was an attractive target for the lefty power hitter.40 Publicly, at the time, Altman put a positive face on the deal – but he later wrote, “To say that I was shocked would definitely be an understatement.”41

Altman’s one season in St. Louis was disappointing: .274-9-47 in 135 games. Injuries remained a factor, but he also admitted that he had been pressing too much to take advantage of the short porch. “Hitting the ball there seemed easy and I tried to pull entirely too much. It fouled me up.” He also cited platooning. “When I’m going right,” he noted, “it doesn’t matter whether I’m batting against lefthanded or righthanded pitching.”42 Yet another ingredient was impaired vision. He tried playing with glasses, but they were uncomfortable and got steamed up in the muggy summer air of St. Louis.43

Altman was traded again in November 1963, going to the New York Mets along with pitcher Bill Wakefield for Roger Craig. He noted with regret that St. Louis, which finished second in the NL in 1963, went on to become World Series champions the next year.44 Except for 1967, when he played just a fraction of the year in the majors, the ’63 Cardinals were his only big-league team that finished above .500.

Again, Altman spent just one season with his new team while playing hurt. As the primary starting left fielder for the cellar-dwelling Mets, his homer and RBI totals were identical to 1963’s (9 and 47), but his batting average tailed off to just .230. Altman summed it up frankly: “The year with the Mets was probably the least amount of fun I had in baseball, considering the difficulties with my wife, me not hitting and the team losing . . . the injuries always frustrated me.”45

For the third time in three years, Altman was traded. He went back to Chicago in January 1965, in an even-up swap for another outfielder, Billy Cowan. Cowan, then aged 26, had been voted the minor league player of the year in 1963. The Mets envisioned him as their regular center fielder. Meanwhile, press reports suggested that Altman had been obtained as first base insurance for Ernie Banks.46

The return to the Cubs did not revive Altman’s career. He started well in 1965 but got hurt yet again. “I had so many injuries over those few years, most of them to my legs and groin muscles,” Altman recalled. “One sportswriter said that my team was Blue Cross.” This time, he suffered a severe groin tear while running to first after trying to bunt his way on.47 Overall in 1965 and 1966, his batting numbers were uninspiring: a total of 9 homers and 40 RBIs in 178 games, with an average of .228.

Altman also believed that Leo Durocher, who became Chicago’s manager in 1966, “soured on me a little because of my wife . . . in those days you weren’t supposed to have mixed marriages. It may or may not have been true, but that was my perception.”48

The last 15 games that Altman played in the majors came in 1967. He spent most of the season with Tacoma in the Pacific Coast League. Yet even though he was aged 34, he was far from finished. In fact, he embarked on a very fruitful new phase of his career.

In Tacoma, Altman had become acquainted with Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada, a Japanese-American who was then the general manager of the Cubs’ farm team in the California League. Harada, who was well-connected in Japanese baseball, asked Altman if he wanted to play there.49 Altman agreed. His hope (as it had been when he accepted the demotion to Tacoma) was to stay healthy, play well, and get noticed. He thought he would be back in the majors after a year or so.50

When Altman arrived in Japan, he realized something that struck many gaijin (foreign) players. “They do things over there that are a loooooot different, and one thing was the spring training. I call it kamikaze training.”51 He was referring to how long and grueling the practice sessions were. However, the type of training he had done for John McLendon helped him.52

Altman spent his first season in Japan with the Tokyo Orions. The franchise changed its name to the Lotte Orions in 1969 after being sold to the Korean company Lotte. During seven seasons with the Orions, Altman hit 193 home runs and drove in 609 in 821 games. He hit below .300 only in 1969. His strong batting came despite what he viewed as another glaring disparity: “Americans had a different strike zone than Japanese players. Balls and strikes could be anywhere.”53

Nonetheless, Altman succeeded where many gaijin failed. He worked hard and made an effort to learn the Japanese language and customs. He noted, “You had to have a certain temperament and the ability to roll with things even if they seemed outrageous.”54

In 1974, Altman was hitting better than he ever had in Japan – .351, with 21 homers and 67 RBIs in just 85 games. However, that August, about three-quarters of the way through the season, he was diagnosed with colon cancer and underwent chemotherapy.55 The treatment was successful, but Lotte’s manager, former star pitcher Masaichi Kaneda, and Altman had a strained relationship. According to Altman, “Kaneda wanted to sign another American and have me around as coach . . . just as an insurance policy. . .He wanted to cut my salary to the bone.” For all intents and purposes, Altman was a free agent, but the bad press that Kaneda fomented scared many teams away. Finally, the Hanshin Tigers gave Altman a chance.56

In his final season, 1975, Altman hit .274-12-57 in 114 games. He started strongly but then slumped. “I think my body was weaker than I thought,” he later admitted. “I was feeling the lingering effects of the chemotherapy.” He also noted that Hanshin’s ballpark was bigger and the prevailing winds blew in from right field, which was hard on him as a dead-pull lefty hitter.57

Altman had previously said that he would continue to play until he had a subpar season. He decided to retire from baseball, and returned to Chicago, where he spent 13 years as a commodities trader, buying a seat on the Chicago Board of Trade. He said, “Wherever I played, one thing on my side was my competitive nature,” and the same held true in his new line of work. He also brought that spirit to his new sports, racquetball and later horseshoes.58

Altman got married for the second time in 1976 to Etta Allison, a piano teacher.59 He continued to trade commodities out of his home; in addition, he ran a prepaid legal services business. He also volunteered with the Boys Foundation and mentored youth within the community. He stated an intense interest in keeping kids off drugs and alcohol and out of trouble.60

Around 2002, Altman and Etta moved to O’Fallon, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis. In his eighties, Altman remained in good health and his memory was excellent. He was invited in 2016 to open SABR’s 19th annual Jerry Malloy Negro Leagues Conference and regaled the audience with many anecdotes.

With regard to the presence of African-Americans in baseball today, Altman said, “You just have to work hard, study and concentrate, and just be there when your chance comes along. The young black American player just isn’t pursuing baseball like they did in the past. But baseball offers so many opportunities, so I would think that black players would look at baseball more.”61

Looking back on his long and successful life, George Altman reflected, “I feel I could have been a star in the major leagues, but things worked out pretty well in another way. I did okay. I have a lot of good baseball memories. I met a lot of good people.”62

Last revised: January 31, 2017

Sources

The backbone of this biography is George Altman’s full-length autobiography, co-authored with Lew Freedman, George Altman: My Baseball Journey from the Negro Leagues to the Majors and Beyond, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013. Grateful acknowledgment to Mr. Altman for additional input (telephone interview, January 24, 2017).

Special thanks also to Laura Altman Jones for the introduction to her father and to Gina Rodgers-Sealy for the introduction to Laura. Gina’s father, André Rodgers, and George Altman were close friends while they were teammates on the Cubs. Their daughters have remained good friends since childhood.

Internet resources

Negro League Baseball eMuseum (http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/altman.html)

comc.com (online baseball card database)

Notes

1 George Altman, 7, 13.

2 George Altman, v, 7,8. Telephone interview, George Altman with Rory Costello, January 24, 2017 (hereafter Altman interview).

3 Jack Lee, “Andersons [sic] of Goldsboro Excited over Son’s Play,” Gastonia (North Carolina) Gazette, April 17, 1959, 18.

4 George Altman, 12, 25.

5 Ryan Whirty, “George Altman Kicks Off the Malloy!”, Home Plate Don’t Move blog, July 7, 2016.

6 George Altman, 11, 35.

7 McLendon coached the Cleveland Pipers of the American Basketball League – owned by George Steinbrenner – for part of the 1962 season. He also coached the Denver Rockets of the American Basketball Association for part of the 1969 season.

8 George Altman, 21, 24.

9 George Altman, 22, 28, 30.

10 George Altman, 31.

11 Ed Prell, “Cubs’ Flash Altman Sized Up by Cobb as Natural Power Hitter,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1959, 14.

12 George Altman, 39.

13 Whirty, “George Altman Kicks Off the Malloy!”

14 George Altman, 42. Later press accounts support the $11,000 figure.

15 George Altman, 43, 44.

16 George Altman, 45.

17 George Altman, 49.

18 “Fort Carson Wins All-Army Title in Four-Game Sweep,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1957, 53.

19 Jerry Holtzman, “Bruin Briefs,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1958.

20 Leo J. Eberenz, “Sugar Kings Clinch Flag in First Season,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1969, 24.

21 Edgar Munzel, “Cubs’ Fortunes Soar on Clouts by Skyscraper George Altman,” The Sporting News, September 30, 1959, 35.

22 Jerry Holtzman, “Cubs’ Tanner Traded to Hub for Bob Smith,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1959.

23 Jerry Holtzman, “Scheffing’s Only Forecast: ‘Cubs Will Win More,’” The Sporting News, April 8, 1959, 18.

24 Wendell Smith, “Banks Lamps Some Coming Colored Stars,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1959, 12.

25 George Altman, 54.

26 George Altman, 147.

27 Edgar Munzel, “Altman Nails Down Bruins’ Picket Post on Solid Whacking,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1959, 19.

28 George Altman, 56.

29 Munzel, “Altman Nails Down Bruins’ Picket Post on Solid Whacking”

30 Ruben Rodriguez, “Five Major Records Set by Elephants,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1960, 29.

31 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003: 461.

32 “Puerto Rico’s Tommy Davis Wins Series Batting Crown,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1960, 28.

33 George Altman, 62, 74, 77.

34 George Altman, 67, 74.

35 George Altman, 88.

36 George Altman, 190.

37 George Altman, 80.

38 Jerry Holtzman, “Cubs see Jackson as Man to Doll up Dreary Hill Corps,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1962, 11

39 George Altman, 81.

40 Neal Russo, “Slugger Altman Sees Card Wall as Choice HR Target,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1962, 11.

41 George Altman, 96.

42 Barney Kremenko, “Mets Give Roger ‘A’ for Effort, Plan Next House-Cleaning Step,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1963, 9.

43 George Altman, 100, 103.

44 George Altman, 113.

45 George Altman, 113.

46 “Mets Trade Altman to Cubs for Cowan,” Associated Press, January 16, 1965.

47 George Altman, 117.

48 George Altman, 120.

49 George Altman, 125.

50 George Altman, 127.

51 Whirty, “George Altman Kicks Off the Malloy!”

52 George Altman, 25.

53 George Altman, 135.

54 George Altman, 145.

55 George Altman, 166.

56 George Altman, 169.

57 George Altman, 171.

58 George Altman, 189, 190.

59 Altman interview.

60 George Altman, 183.

61 Whirty, “George Altman Kicks Off the Malloy!”

62 George Altman, 189.

Full Name

George Lee Altman

Born

March 20, 1933 at Goldsboro, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.