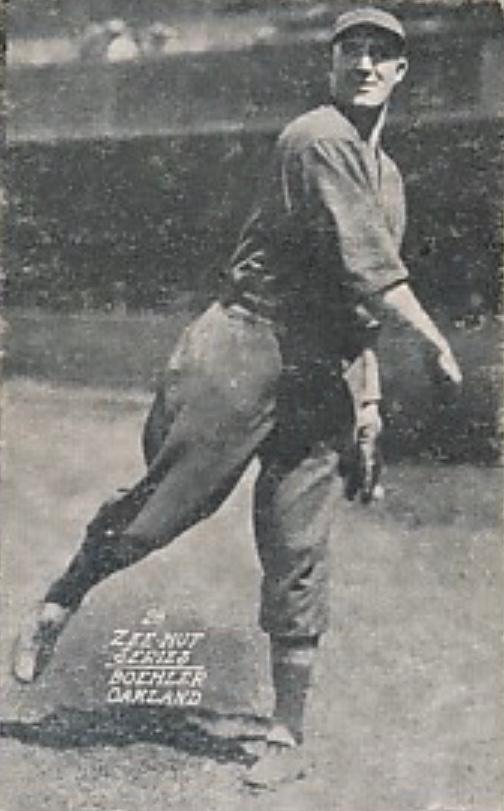

George Boehler

George Boehler is “the ace of the minor leagues.”1 — Nathan E. Jacobs, Omaha News, 1923

Pitcher George “Rube” Boehler had a blazing fastball and a sweeping curve.2 In the minors from 1911 to 1930, he won 249 games3 and was a seven-time 20-game winner. For the 1922 Tulsa Oilers, he won 38 games, a single-season mark unmatched in professional baseball from 1909 through 2023.4 Throughout his career, he ping-ponged between minor and major leagues. He was given only sporadic opportunities in the majors, primarily owing to his lack of control.

Pitcher George “Rube” Boehler had a blazing fastball and a sweeping curve.2 In the minors from 1911 to 1930, he won 249 games3 and was a seven-time 20-game winner. For the 1922 Tulsa Oilers, he won 38 games, a single-season mark unmatched in professional baseball from 1909 through 2023.4 Throughout his career, he ping-ponged between minor and major leagues. He was given only sporadic opportunities in the majors, primarily owing to his lack of control.

George Henry Boehler was born on January 2, 1893, in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, and grew up in that Ohio River town, 25 miles west of Cincinnati. He was of German descent, the youngest of three children born to George and Emma (Stein) Boehler. Lawrenceburg was known for whiskey production; George Sr. worked at a distillery.5

Young George pitched for local amateur teams. In a 13-inning contest in September 1910, he struck out 17 batters.6 He was a big right-hander, about 6-foot-1 and 175 pounds.7

The Indianapolis Indians of the Class A American Association signed Boehler to a contract and optioned him to the Springfield Reapers of the Class D Ohio State League.8 On April 20, 1911, he defeated Marion in Springfield’s season opener.9 Three days later, he pitched a no-hitter in a 7-1 triumph over Lima.10 He posted a 12-6 record for the pennant-winning Reapers.

A right-handed batter, Boehler was a weak hitter early in his career. Through games of July 6, 1911, he managed only one hit in 49 at-bats for a microscopic .020 batting average.11 But his hitting improved; eight years later he batted .269.

In 1912 Indianapolis assigned Boehler to the Newark Molders of the Ohio State League.12 In 364 innings pitched, he achieved a 27-17 record. He delivered three-hit shutouts of Mansfield on May 13 and August 20, and fanned 14 in a three-hitter against Lima on August 2.13 At times, he struggled with his control; on July 16, he walked 10 batters in a 10-5 loss to Portsmouth.14

Upon the recommendation of scouts Bobby Lowe and Bill Donovan, the Detroit Tigers purchased Boehler’s contract for $3,000.15 The rookie debuted on September 13, 1912, at Navin Field in Detroit. He started and went seven innings against the Washington Senators, allowing eight runs on 12 hits. Detroit came back from an 8-1 deficit and won, 9-8. In five appearances with the Tigers that year, Boehler allowed 50 hits in 32 innings, and his record was 0-2 with a 6.47 ERA. But the Tigers saw his potential.

Detroit catcher Oscar Stanage said Boehler “has as much stuff as any youngster he ever saw.”16 Boehler’s fastball had unpredictable late movement, and his curve had a wide, quick break. He also mixed in a spitball.17 After Tigers pitcher George Mullin taught him a change of pace, Mullin declared, “He has everything that a pitcher needs.”18

But Boehler still lacked control. On April 15, 1913, in Detroit’s fourth game of the season, he pitched a complete game at Cleveland and was soundly beaten, 9-0. He walked six batters and hit three with pitches: Nap Lajoie, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and pitcher Cy Falkenberg. Jackson was beaned, “and the shoeless wonder dropped to the ground as though slain. He was revived in due time and took his hard-won place on first base.”19

It was clear that the 20-year-old Boehler needed further seasoning. The Tigers optioned him to the St. Joseph (Missouri) Drummers of the Class A Western League. “He’ll be a great pitcher as soon as he gets control,” predicted Detroit manager Hughie Jennings.20

Boehler demonstrated in 1913 that he could dominate Class A hitters. He compiled a 27-13 record for the Drummers in 345 innings. Batters averaged .208 against him. His 2.32 ERA was the best in the league among pitchers with at least 160 innings pitched, and his 244 strikeouts ranked second in the league (behind Red Faber’s 265).21

Boehler returned to the Tigers in 1914, but he appeared in only 18 of the team’s 157 games, six as a starter and 12 as a reliever. In 63 innings pitched, he walked 48 batters, a rate of 6.9 per nine innings. He earned his first major-league victory on June 15, 1914, defeating the New York Yankees, 4-1. In nine innings, he allowed six hits and walked eight. His second win came on June 27 against the Chicago White Sox. In that one, he allowed no runs and two hits in 6 1/3 innings, but he walked seven and hit two batters. Even in victory, he was wild.

In the offseason Boehler worked as a barber in Lawrenceburg. On April 13, 1915, he married Edom Pauline Oester.22 She, too, was of German ancestry.

Boehler spent the entire 1915 season with the Tigers but was barely used: eight appearances, all in relief, and 15 innings pitched. Manager Jennings did not trust him in games as the Tigers vied for the pennant. But, as sportswriter Harold V. Wilcox of the Detroit Times explained, Jennings did not want to let Boehler go, out of fear that an American League rival might pick him up and use him against the Tigers.23 “Few pitchers in the major leagues … can throw the sphere with more speed than Boehler can [in] the opinion of his teammates.”24

The Detroit coaching staff had given Boehler “enough tutoring to develop a [Christy] Mathewson,” said Wilcox, yet he sat “wasting away” on the Tigers bench.25 Newspapermen figured that his inactivity was rooted in untamed wildness. The less he pitched, the more his reputation as a “wild man” grew.

Boehler appeared in five games for Detroit in 1916. His last appearance, at Washington on May 16, sealed his fate with the team. He started but was taken out after facing four batters; he hit the leadoff man with a pitch and then gave up a single and two walks. The Tigers decided he no longer fit into their plans, and they sent him to the Louisville Colonels of the Class AA American Association. He pitched for Louisville for three weeks in July26 and finished the season with the Syracuse Stars of the Class B New York State League. In the offseason he was purchased by the Denver Bears of the Western League.27

With the 1917 Bears, Boehler posted a 9-5 record and 2.54 ERA in 145 innings. His season was cut short when he developed a sore arm in June.28 The following spring, after a brief trial with the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Class A Southern Association,29 he returned to the Western League as a member of the Joplin (Missouri) Miners. He played mostly in the outfield with the 1918-19 Miners and pitched infrequently because of arm trouble.30

Boehler revived his pitching career with the 1920 Miners. In 334 innings, he compiled a 20-17 record. He led the league with 258 strikeouts31 and allowed only 2.2 walks per nine innings. This fine season earned him a return trip to the American League.

The St. Louis Browns purchased Boehler’s contract in September 1920 for a reported $8,000, outbidding a $6,000 offer from the Chicago Cubs.32 He started for the Browns at Detroit on September 24 and took the loss; he went five innings and surrendered eight runs. To reduce their roster to meet a 25-player limit, the Browns released him to the Tulsa Oilers of the Western League on May 18, 1921.33 The Oilers paid $5,000 to get him.34

On May 31, 1921, the Oilers played a doubleheader against the Oklahoma City Indians at McNulty Park in Tulsa. Immediately after the twin bill, the Oilers left the city and headed to Wichita for their next series. That night, the African American community of Greenwood, one mile from McNulty Park, was victimized by the horrific Tulsa race massacre. Thirty-five square blocks were burned to the ground by white rioters and as many as 300 residents were killed in attacks.35

Yet the Oilers’ season continued. Pre-massacre, they were in second place with a 24-19 record.36 Post-massacre, they went 41-84 and finished in last place. It was an off year for Boehler: In 193 innings pitched, his record was 4-20. But a turnaround was coming in 1922.

With a record of 24-26 through games of June 7, the 1922 Oilers were in the middle of the pack.37 They went 80-38 after June 7 to claim the pennant.38 Boehler was the ace of the pitching staff with a remarkable 38-13 record. His record was 33-11 in 47 starts and 5-2 in 15 relief appearances.39 He led the league in innings pitched (441) and strikeouts (333).40 The Tulsa World said, “there is not a better natured and harder working ball player to be found anywhere than Big George.”41

In a postseason series, the Oilers defeated the Mobile Bears, champions of the Southern Association, in six games (four games to one with one tie). Boehler made three appearances and allowed two runs on seven hits in 18 innings. He was the winning pitcher of the second game of the series.42 Including the postseason, he amassed 39 wins in 459 innings.

Naturally, major-league scouts were buzzing. The Oilers entered into an agreement with the Pittsburgh Pirates: Boehler would receive a trial with the Pirates, and if they kept him, they would “send a surplus youngster or two to Tulsa and likewise $25,000 in cash”43 (about $450,000 in 2023 dollars). At spring training with the Pirates in 1923, Boehler showed “more stuff than any pitcher on the team,” and the Pirates decided to keep him.44

On April 18, 1923, in the second game of the Pirates’ season, Boehler pitched a complete game but lost 7-2 to Grover Alexander and the Chicago Cubs. In his next two starts, he defeated the Cincinnati Reds on April 23, but lasted only two innings in a loss to the St. Louis Cardinals a week later.

In Pittsburgh on July 5, Boehler pitched a complete game in an exhibition against the New York Yankees, which the Yankees won, 9-8. The fans were there to see Babe Ruth hit a home run. Boehler did as instructed and grooved a pitch to him in the ninth inning, which the Bambino clouted over the right-field fence.45

Boehler was seldom used by the Pirates. In 10 regular-season appearances, he walked 26 batters in 28 1/3 innings and his ERA was 6.04. His disappointing performance was attributed to a sore arm.46 On July 28, he was optioned to the Western League’s Omaha Buffaloes, for whom he posted a 7-9 record in 139 innings.47 In the offseason, the Pirates traded him to the Oakland Oaks of the Class AA Pacific Coast League.48

Boehler was a workhorse for the Oaks. He went 26-21 in 1924 and 23-25 in 1925, leading the league in innings pitched and strikeouts each year.49 In Los Angeles on July 18, 1924, the “iron man” won both games of a doubleheader, allowing one run and eight hits in 18 innings.50 Against Sacramento on May 28, 1925, he pitched a no-hitter for nine innings but lost 2-0 in 10 innings. He struck out 15 batters in that contest.51

“Boehler has more stuff than any hurler in the league,” said sportswriter Eddie Murphy of the Oakland Tribune.52 The Brooklyn Robins drafted him, and he joined the team in the spring of 1926. At age 33, he was headed back to the majors.

Boehler thrived when given steady work, but he spent the entire 1926 season with the Robins and pitched only 34 2/3 innings. He was given only one start, which he won, at Philadelphia on May 28. Sportswriter Thomas Holmes of the Brooklyn Eagle said Boehler is a “real big league pitcher. . .handicapped by the abundance of other pitching talent” on the team. He had “no chance” with the Robins.53

The Robins returned Boehler to the Oaks after the season. This marked the end of his major-league career. He pitched a total of 202 1/3 innings in the majors over nine seasons, with a 6-12 record and a 4.71 ERA. He averaged 6.0 walks per nine innings. With better control, he may have had a more extensive major-league career.

The Oaks won the PCL pennant in 1927, and Boehler was their ace. His record was 22-12 with a 3.10 ERA, and he led the league in wins and strikeouts.54 The next year he went 17-14 with a 4.10 ERA. But the end of his career was near. In 62 innings pitched for the Oaks and Los Angeles Angels in 1929, his record was 2-6 with a 7.40 ERA. He struck out 26 batters and walked 67.55 (While in southern California, he was one of several ballplayers who appeared in the 1929 movie, Fast Company.56)

In August 1929, Boehler was sold to the Nashville Volunteers of the Southern Association.57 He pitched in a few games for Nashville that year and in 27 games the following year. Rather than accept an assignment to the Peoria club in the Class B Three-Eye League, he voluntarily retired from professional baseball in July 1930.58

Boehler and his wife resided in Greendale, a town adjacent to Lawrenceburg. He pitched for local semipro teams until about 1936. At age 42, he threw a no-hitter for a Brookville, Indiana, team in a night game at Indianapolis on July 31, 1935.59

Boehler worked as a millwright60 and was employed by the James Walsh & Company Distillery in Lawrenceburg for about 25 years, until his retirement in the spring of 1958. After a lingering illness, he died at his home in Greendale on June 23, 1958, at the age of 65.61 His death certificate says neck cancer was the cause. He was interred at the Greendale Cemetery.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Sources

Ancestry.com, Baseball-reference.com, and Retrosheet.org, accessed August 2023.

Notes

1 Nathan E. Jacobs, “Burch Rods Play Two Games with Des Moines Today,” Omaha News, August 19, 1923: Sports, 2.

2 Ralph L. Yonker, “Call George Boehler a Second Walter Johnson,” Detroit Times, April 8, 1913: 1.

3 SABR, Minor League Baseball Stars, Revised Edition, Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press (1984): 102. This reference shows 248 career wins in the minor leagues, but it does not include the win Boehler earned while pitching for the 1916 Louisville Colonels; see “Pitching Records,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 30, 1916: 8-10.

4 SABR, Minor League Baseball Stars, Revised Edition: 10. In 1906 Stoney McGlynn won 41 games and Rube Vickers won 39 games in the minors. In 1908 Ed Walsh won 40 games for the Chicago White Sox.

5 1910 US census.

6 “Sports, Amusements and Otherness,” Aurora (Indiana) Bulletin, September 9, 1910: 1. Boehler was the winning pitcher as the Hoosiers defeated Climax, 3-2.

7 Boehler’s World War II draft registration gives his height as 6-foot-1.

8 “Weeding Out Process at Washington Park,” Indianapolis News, March 29, 1911: 10.

9 Jack Reid, “Diggers Lose to Springfield,” Marion (Ohio) Mirror, April 21, 1911: 3.

10 “No-hit Game for Boehler,” Springfield (Ohio) News, April 24, 1911: 5.

11 “Ohio State Batting Averages up to July 6, 1911,” Marion (Ohio) Star, July 8, 1911: 9.

12 “Big League Scouts Are Watching Pitcher Boehler,” Springfield News, June 4, 1912: 9.

13 “Mansfield Is Shut Out by Newark,” Mansfield (Ohio) News, May 14, 1912: 10; “Rube Boehler Fans Fourteen Stogies, Permits 3 Hits, 1 Run,” Lima (Ohio) Republican-Gazette, August 3, 1912: 7; “Mansfield Loses Both at Newark,” Mansfield News, August 21, 1912: 8.

14 “Boehler Was Wild,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 17, 1912: 10.

15 “Pitcher Boehler Sold to Detroit,” Mansfield News, July 25, 1912: 10.

16 “Cobb and Stanage at War,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News, January 30, 1913: 3.

17 Yonker, “Call George Boehler a Second Walter Johnson.”

18 “Tiger Recruit Hurlers Offer Varied Assortment,” Detroit Times, March 8, 1913: 1.

19 E.A. Batchelor, “Recruit Hurler Is Clouted by Naps Who Win Shutout,” Detroit Free Press, April 16, 1913: 10.

20 “George Boehler Gains Control by Cutting Out Extensive Wind-up,” Detroit Times, April 21, 1913: 6.

21 Francis C. Richter, ed., The Reach Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1914, Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Co. (1914): 267, 268.

22 “Boehler–Oester,” Aurora Bulletin, April 16, 1915: 1. It seems that the couple had no children; their US census records from 1920, 1930, and 1940 show no children.

23 Harold V. Wilcox, “If Steen Makes Good Boehler Can Expect to Hear Tin Rattling,” Detroit Times, June 16, 1915: 6.

24 “Billy Sullivan’s Work Causes Hope of Tiger Fans to Rise Flagward,” Lansing (Michigan) State Journal, March 22, 1916: 8.

25 Harold V. Wilcox, “Team Speeding West after Fine Visit in East—Win 10, Lose 5,” Detroit Times, August 13, 1915: 6; Harold V. Wilcox, “Connie Mack Can’t Come Through with Winner on Schedule, Is Belief,” Detroit Times, September 22, 1915: 6.

26 “Pitching Records,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 30, 1916: 8-10. In 34 innings pitched for Louisville, Boehler had a 1-1 record and 5.03 ERA.

27 John H. Farrell, “National Association Bulletin,” Sporting Life, November 11, 1916: 9.

28 “Pitchers Go Up in Denver,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), June 11, 1917: 3.

29 “Lohman Proves Pinch Pitcher,” Chattanooga News, May 2, 1918: 10.

30 Lou Duffy, “Boehler’s Delivery Rivals Electrical Storm at Ball Park,” Tulsa Tribune, May 27, 1920: 13.

31 SABR, Minor League Baseball Stars, Revised Edition, 102.

32 “Personal Paragraphs,” Lawrenceburg (Indiana) Register, September 16, 1920: 5; Harry F. Pierce, “Yankees 4, Browns 3,” St. Louis Star, September 20, 1920: 18.

33 “George Boehler to Join Tulsa’s Staff,” The Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), May 19, 1921: 10.

34 B.A. Bridgewater, “Boehler Declines Job with Browns; Would Rather Pitch for the Oilers,” Tulsa World, November 5, 1922: 14.

35 J. Paul, “Sport as a Place of Violence in the Tulsa Race Massacre,” African American Intellectual History Society, at aaihs.org, June 7, 2021, accessed September 2023; “1921 Tulsa Race Massacre,” Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, at tulsahistory.org, accessed September 2023.

36 “The Standing,” Kansas City Kansan, June 1, 1921: 9.

37 “The Club Standings,” Tulsa World, June 8, 1922: 8.

38 “The Club Standings,” Tulsa World, September 26, 1922: 11. The Tulsa Oilers finished the 1922 season with a 104-64 and won the Western League pennant, six games ahead of the second-place St. Joseph (Missouri) Saints.

39 “Boehler’s Record,” Tulsa Tribune, September 24, 1922: 12. Boehler’s record as a starter and reliever was determined by the author from box scores.

40 SABR, Minor League Baseball Stars, Revised Edition: 102.

41 “All Pittsburgh Hoping Boehler Delivers Goods,” Tulsa World, March 31, 1923: 16.

42 Lou Duffy, “Winning Class ‘A’ Worlds Baseball Championship Crowning Achievement of Tulsa Sports History,” Tulsa Tribune, December 31, 1922: 10-B; B.A. Bridgewater, “Lelivelt Hits Homer–Tulsa Wins 3 to 1,” Tulsa World, October 7, 1922: 1, 11.

43 Edward F. Balinger, “New Pirate Deals May Add Strength to Hurling Staff,” Pittsburgh Post, December 17, 1922: 26.

44 William Peet, “What the Post Clock Saw,” Pittsburgh Post, June 22, 1923: 13; James M. McAfee, “Des Moines Foe of Buccaneers Today,” Pittsburgh Press, April 6, 1923: 32.

45 “Bambino Gets Homer; Yanks Win over Bucs,” Pittsburgh Press, July 6, 1923: 32.

46 “Boehler Goes to Wild West under Option,” Pittsburgh Post, July 29, 1923: 25.

47 Baseball-reference.com, accessed September 2023, indicated that Boehler pitched for both Omaha and Tulsa in 1923, but an inspection of box scores by the author revealed that he pitched only for Omaha that year.

48 Charles J. Doyle, “Pirates Acquire Coast League Mound Ace,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, December 13, 1923: 13.

49 SABR, Minor League Baseball Stars, Revised Edition: 102.

50 “Boehler Pulls Iron Man Stunt,” Tacoma Ledger, July 19, 1924: 6.

51 Eddie Murphy, “Miller Says Boehler Second Only to Dazzy Vance,” Oakland Tribune, May 29, 1925: 12.

52 Eddie Murphy, “Success of Oaks Attributed to Flowers and Giusto,” Oakland Tribune, May 11, 1925: 14.

53 Thomas Holmes, “Boehler, Real Big League Pitcher, Has No Chance with Robins,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 11, 1926: C3.

54 SABR, Minor League Baseball Stars, Revised Edition: 102.

55 SABR, Minor League Baseball Stars, Revised Edition: 102.

56 Fast Company, Turner Classic Movies, at tcm.com, accessed September 2023.

57 “Foul Tips,” Los Angeles Times, August 9, 1929: III-3.

58 Freddie Russell, “Sideline Sidelights,” Nashville Banner, July 27, 1930: 23.

59 “George Boehler Pitches No-hit Game under Lights,” Lawrenceburg Register, August 15, 1935: 1.

60 1940 US census.

61 “Deaths: George Boehler, 65, Dies in Greendale Home Monday,” Lawrenceburg Press, June 26, 1958: 2-7.

Full Name

George Henry Boehler

Born

January 2, 1892 at Lawrenceburg, IN (USA)

Died

June 23, 1958 at Lawrenceburg, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.