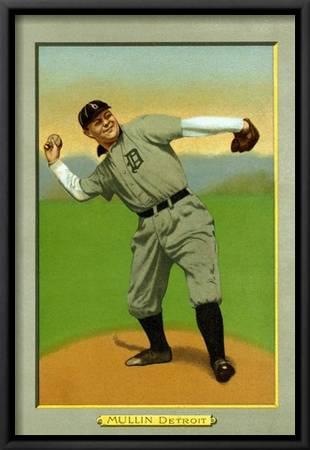

George Mullin

Powerfully built with a fearful fastball and biting curve that Johnny Evers once referred to as a “meteoric shoot,” George Mullin was Detroit’s stalwart right-handed pitcher for 12 years. He was nicknamed “Wabash George” or “Big George” in reference to his 6’0″, 188 lb. frame, though his weight routinely fluctuated throughout his career. A double threat, Mullin also earned a reputation as a batter to be feared, finishing his career with an impressive .262 batting average. During his prime with the Tigers, Mullin established himself as one of the game’s best cold-weather pitchers, an asset which served him well pitching in Detroit’s frigid climate. As Alfred Spink once observed, “[Mullin] is one of the few veteran twirlers who is able to jump right in at the start of the season and do good work.”

Powerfully built with a fearful fastball and biting curve that Johnny Evers once referred to as a “meteoric shoot,” George Mullin was Detroit’s stalwart right-handed pitcher for 12 years. He was nicknamed “Wabash George” or “Big George” in reference to his 6’0″, 188 lb. frame, though his weight routinely fluctuated throughout his career. A double threat, Mullin also earned a reputation as a batter to be feared, finishing his career with an impressive .262 batting average. During his prime with the Tigers, Mullin established himself as one of the game’s best cold-weather pitchers, an asset which served him well pitching in Detroit’s frigid climate. As Alfred Spink once observed, “[Mullin] is one of the few veteran twirlers who is able to jump right in at the start of the season and do good work.”

George Joseph Mullin was born in Toledo, Ohio on July 4, 1880, one of five children of Irish immigrant parents Martin and Helen (Kelly) Mullin. As a youngster, George worked part-time as messenger boy and attended St. John’s Jesuit Academy in Toledo. By 1898, Mullin was engaged in semi-pro ball and over the next three years played for Wabash and South Bend in Indiana. In 1901, Mullin signed his first professional contract with Fort Wayne of the Western Association. “Big George” became a workhorse for his new club, hurling 367 innings en route to a 21-20 mark. After the season, Mullin signed a contract with Brooklyn of the National League, but broke the agreement before ever appearing in a Superbas uniform, as he accepted a more lucrative offer from the Detroit Tigers.

Mullin was 21 when he entered the major leagues on May 4, 1902, at Bennett Park in Detroit. A week later he made his debut start at home against Chicago, surrendering nine runs over 8⅓ innings in a no-decision against the White Sox. In an early display of his hitting prowess, Mullin also cracked three doubles in the game. A regular in the Detroit rotation for the rest of the season, Mullin’s rookie season was mixed: he pitched himself to a 13-16 record in 30 starts, but also batted .325 (which would remain a career high) in 120 at-bats.

A crafty pitcher, Mullin’s arsenal included more than his excellent stuff. Like Mark Fidrych, the Tigers’ pitcher of the late 1970’s, Mullin perfected a number of eccentric strategies to gain an advantage over hitters. At critical times, Mullin chose the “stall,” wherein he distracted the batter with tactics of walking off the mound, loosening or tightening his belt, fixing his cap, re-tying his shoes, and removing imaginary dirt from his glove. Mullin also incessantly talked to himself, to batters, and to fans of opposing teams who would heckle him when he engaged in his act. Mullin was also superstitious and believed team mascot Ulysses Harrison, an African-American orphan whom the players nicknamed “Li’l Rastus,” brought him good luck.

In 1903, Mullin achieved a breakthrough performance with a 19-15 record and 2.25 ERA, though wildness caused him to lead the league in walks, with 106. He continued to lead the circuit in free passes every year through 1907, but during that time he also developed into one of the league’s most durable pitchers. He led the league in innings pitched with 347⅔ in 1905, and in September 1906 he started and won both ends of a doubleheader against Washington. Mullin ran off a string of three consecutive 20-win seasons from 1905 to 1907, though during that span he also lost 20 games twice, in 1905 and again in 1907. In his first taste of the fall classic against the Chicago Cubs in 1907, Mullin lost both his starts despite pitching two complete games and notching a sterling 2.12 ERA.

The following year, Mullin struggled to a 17-13 mark with a poor 3.10 ERA, but overcame his difficulties to capture the Tigers’ only victory in the 1908 World Series, an 8-3 complete game victory in Game Three. But it was the 1909 season that was the superlative achievement of his career. Trimming off forty pounds during the offseason, Mullin pitched a one-hitter against Chicago on opening day as the first act in what proved to be a personal 11-game winning streak to start the season. His first loss of the year finally came on June 16, 5-4 to the Athletics. Mullin finished the season 29-8 with a 2.22 ERA, leading the AL in wins and winning percentage (.784). He was second with 303⅔ innings pitched, and in a sign of his improved control, gave up only 78 walks.

Returning to the World Series for the third straight year, Mullin drew the Game One starting assignment, losing to Babe Adams of the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field by a score of 4-1. With Pittsburgh leading 2-1 after three games, Mullin started Game Four in Detroit against the Pirates’ Lefty Leifield. Mullin limited Pittsburgh to five hits and pitched a 5-0 complete game shutout, squaring the series at two games apiece. The teams returned to Pittsburgh where Babe Adams won his second game of the Series, 8-4. Facing elimination in Game Six at Detroit, Mullin started his third game and gave up three runs in the first inning, before settling down to pitch seven straight innings of shutout ball in a 5-4 Detroit victory.

After Detroit starter Bill Donovan was knocked out of the box early in the decisive Game Seven, Tigers manager Hughie Jennings turned to Mullin, who was unable to hold the Pirates as Pittsburgh cruised to an 8-0 victory. Despite the poor performance, Mullin finished the Series with an impressive 2-1 record and 2.25 ERA in 32 innings pitched, the latter still a major league record for a seven-game series. Detroit, however, would not return to the World Series for another 25 years, and Mullin never again pitched in the postseason.

With his career year behind him, Mullin pitched two distinguished seasons out of the next three. He posted winning records of 21-12 and 18-10 in 1910 and 1911, respectively, but fell to 12-17 in 1912, his last full season with Detroit. Despite being out of condition for most of the season, Mullin achieved a number of milestones in 1912. On May 21, he faced Walter Johnson at Washington and out-dueled him 2-0 for his 200th career victory. On June 22, with the Tigers trailing Cleveland 11-3 with two outs in the bottom of ninth, Jennings chose Mullin to pinch hit for Ty Cobb who had gone to the clubhouse. Mullin ended the game with an out.

In disfavor with management and in decline as a pitcher, Mullin was placed on waivers by Detroit in June. Still unclaimed three weeks after the team’s decision, Mullin was vindicated in the second game of a July 4 doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns at Navin Field. He gave himself a birthday gift of a no-hitter, striking out five and walking five. Mullin iced his performance by delivering three hits and driving in two runs in the 7-0 victory.

Following a feeble 1-6 start — albeit with a much improved 2.75 ERA — to open the 1913 season, Mullin was purchased by the Washington Senators on May 16. He posted a 3-5 record for the year before Washington assigned him to Montreal of the International League. After finishing out 1913 with the Royals, Mullin jumped to Indianapolis of the Federal League in 1914, where he went 14-10. Though he finished his organized baseball pitching career in 1915 at Newark with a 2-2 mark, Mullin continued to participate in semipro baseball as manager and pitcher for various clubs in Indiana and Ohio until 1919. His last position was assistant manager and coach of a club in Rockford, Illinois, of the Three-I League in 1921.

Mullin’s pitching career, while impressive, was certainly influenced by his lack of weight control and conditioning. Dapperly dressed with black hair and blue eyes, he was also the most gregarious of players, enjoying the social life and celebrity of being a major leaguer. Nevertheless, Mullin achieved a set of admirable pitching marks. Over 14 seasons, he was 228-196 (.538) with a 2.82 ERA. A 20-game winner five times in six seasons, he also achieved the distinction (twice) of winning and losing twenty in the same season (1905 and 1907). Mullin still holds four single-season Detroit pitching records for a right hander, all set in 1904: most games started (44); most complete games (42); most innings pitched (381⅓), and most games lost (23). His 209 victories as a Tiger rank second in franchise history.

After baseball, Mullin returned to Wabash where he lived and worked as a police officer. He died at age 63 on January 7, 1944, after a long illness that wasted his robust body to 100 pounds. He was survived by his wife of 43 years, Grace (Aukerman) Mullin, and one daughter, Mrs. Beatrice Rish of Detroit. He was buried in Falls Cemetery in Wabash.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

George Joseph Mullin

Born

July 4, 1880 at Toledo, OH (USA)

Died

January 7, 1944 at Wabash, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.