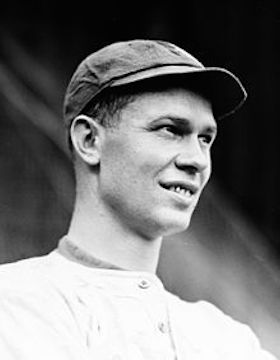

George Zabel

It is a sports cliché that records are made to be broken. But in baseball, changing times and modern playing strategies seem to have put certain major-league bests permanently out of reach. The holders of unapproachable all-time records include immortals like Cy Young, Cal Ripken, Nolan Ryan, Zip Zabel, … Zip Zabel? Indeed, just as Young’s record for most career victories, Ripken’s consecutive-games-played streak, and Ryan’s career strikeouts mark appear unsurpassable, so too does the feat registered by the obscure Zabel, a Chicago Cubs right-hander, on June 17, 1915. Replacing injured starter Bert Humphries with two out in the top of the first inning in a home game against Brooklyn, Zabel was still pitching when the Cubs won the contest by pushing across the deciding run in the bottom of the 19th. Now more than a century later, Zabel’s 18⅓ innings pitched remains the major league record for most innings thrown by a relief pitcher in a single game.

It is a sports cliché that records are made to be broken. But in baseball, changing times and modern playing strategies seem to have put certain major-league bests permanently out of reach. The holders of unapproachable all-time records include immortals like Cy Young, Cal Ripken, Nolan Ryan, Zip Zabel, … Zip Zabel? Indeed, just as Young’s record for most career victories, Ripken’s consecutive-games-played streak, and Ryan’s career strikeouts mark appear unsurpassable, so too does the feat registered by the obscure Zabel, a Chicago Cubs right-hander, on June 17, 1915. Replacing injured starter Bert Humphries with two out in the top of the first inning in a home game against Brooklyn, Zabel was still pitching when the Cubs won the contest by pushing across the deciding run in the bottom of the 19th. Now more than a century later, Zabel’s 18⅓ innings pitched remains the major league record for most innings thrown by a relief pitcher in a single game.

To no great surprise, Zabel began to experience arm problems shortly after his marathon effort. And 1915 was the final season of his brief big-league career. But a destiny of some distinction lay in store for the ex-hurler. The antithesis of his frivolous and infrequently used nickname, “Zip,” Zabel was a sober, serious, and well-educated man who used baseball to achieve other ambitions. In the late-life questionnaire that he submitted to the Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, Zabel indicated that, if he “had to do it all over,” he would again play professional baseball “because it furnished the means for me to go through college.”1 Within a decade of his departure from Organized Baseball, Zabel assumed the post of chief metallurgist for Fairbanks-Morse Company, a large Midwestern manufacturer of heavy equipment. By the time of his retirement in 1948, Zabel was an industry-honored research scientist and the superintendent of foundries maintained nationwide by Fairbanks-Morse. He then devoted the remainder of his life to public service, holding various local and county governmental positions in southern Wisconsin until his death in May 1970 at age 79.

Our subject was born George Washington Zabel on February 18, 1891, in Wetmore, Kansas, a railroad whistle stop in the northeastern corner of the state. He was the youngest of three boys born to farmer Herman Zabel (1856-1903) and his wife, Rosa Belle (née Garvin, 1864-1945).2 Young George attended Wetmore School through his high-school graduation in 1910. He then matriculated to the University of Kansas in Lawrence. Good-sized (eventually 6-feet-2, 184 pounds),3 and an outstanding three-sport athlete (football/basketball/baseball), Zabel became “peeved” when informed that he would not be eligible for Jayhawk varsity teams during his freshman year. Months later, he left Kansas in search of another school.4 In the fall of 1911 Zabel enrolled in Baker University of Baldwin, Kansas, an institution with a more relaxed attitude on participation in school athletics.5 But prior to his arrival at Baker, George took the initial step on the path that would take him to major-league baseball. He agreed to pitch for the Cheyenne Indians, a fast semipro nine organized by Ira Bidwell, a Kansan from nearby Emporia.6

In the estimation of the Denver Post, Cheyenne was “the classiest semi-pro aggregation ever gotten together in the West.”7 Dominating all competition, the Indians captured the state championships of Arizona, New Mexico, Kansas, Nebraska, Utah, Idaho, and Montana, with workhorse hurler George Zabel near-invincible. By summer’s end, his record stood at 36-2 (with two ties), with 328 strikeouts in 49 appearances.8 During this campaign, Pittsburgh Pirates manager Fred Clarke reportedly tried to acquire Zabel,9 but come September, George was back in college, alternating most of his time between the chemistry lab and the gridiron at Baker University.10 When the weather turned, he exchanged helmet and pads for shorts and sneakers, becoming the leading rebounder and defender for the Baker Methodists basketball team.11 And come spring, Zabel took the mound for the varsity nine, notwithstanding the fact that he had already entered the professional ranks, having signed a contract with the Kansas City Blues of the Double-A American Association.12 Zabel, an excellent student who aspired to be a physician or chemist, would remain on campus until the spring semester concluded. He would report to Kansas City in June. In the interim, George kept himself in condition by pitching for Baker.13

We pause here for brief discussion of the Zabel nickname, as it apparently surfaced during this time period. The first-discovered instance of George Zabel being called Zip appears in a somewhat sneering Emporia (Kansas) Gazette recap of a 4-0 Baker victory over Missouri Normal published in April 1912: “Mister Zip Zabel … [made] monkeys of a crowd of sober-minded young ball tossers at the Normal.”14 Because the Gazette was a booster of hometown Emporia College sports teams, the Zip moniker smacks of a partisan putdown of a rival school’s star player. Later iterations of the nickname maintained, improbably, that Zip was derived from the hard-throwing Zabel’s mastery of the “zip ball.”15 Whatever the case, the Zip nickname took root in the Emporia Gazette and, occasionally, the Kansas City Star. Newspapers covering Zabel during his Chicago Cubs years and thereafter were cognizant of the nickname, but rarely used it. Chicago Tribune sportswriters, for example, regularly identified our subject as George Zabel. Or, when in a playful mood, as George Washington or G. Wash Zabel.16 Other newspapers did the same. Why modern baseball reference works have taken to identifying a man known to his contemporaries as George Zabel by the infrequently used nickname Zip is unknown.17 But for the remainder of this bio, he will be referred to as George Zabel.

Zabel’s transition to minor-league play was not a success, at least initially. His repertoire was limited, consisting mainly of a good fastball, and he lacked control and pitching savvy. In early outings, American Association batters quickly demonstrated that Zabel needed seasoning.18 To obtain it, the Blues optioned the young hurler to the Youngstown (Ohio) Steelmen of the Class B Central League.19 There, he benefited from the tutelage of veteran manager Bill Phillips, sharpening his control and adding a quick-breaking curve and a rudimentary changeup to his pitching arsenal. With his Youngstown log standing at a respectable 10-8, Zabel was recalled by Kansas City in late August. Winning three straight late-season games for the Blues sent expectations soaring for the rookie.20 But first, George returned to Baker University for another round of college football, basketball, and chemistry lab.

Completion of his spring course work delayed Zabel’s return to Kansas City until early June of 1913. Once there, his stay with the Blues was brief and rocky. He pitched poorly – later attributed to a case of blood poisoning or to KC manager Charlie Carr’s tinkering with his delivery; Zabel’s excuses varied21 – and was soon dispatched to an American Association rival, the Louisville Colonels.22 There, Zabel mostly pitched batting practice until the Colonels returned him to Kansas City several weeks later.23 No sooner had he unpacked his bags than George was on the move again, sold by Kansas City to the Winnipeg Maroons of the Class C Northern League.24 Here, he suddenly regained form and began the ascent that would find him in a major-league uniform before the season ended.

Once in Winnipeg, Zabel returned to his easy-throwing motion of yore and dominated Northern League batsmen. He won his first nine decisions for the first-place (83-38) Maroons, and finished 10-1. George led circuit pitchers in winning percentage (.909), and fewest walks per nine innings pitched (1.08), while his OBA against (.166 in 108 innings) was second-best.25 Such fine work did not go unnoticed by major-league clubs on the lookout for pitching help. In mid-September, the National League Brooklyn Superbas selected Zabel in the Rule 5 minor-league player draft. Days later, he and infielder Chick Keating were shipped to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for pitcher Fred Herbert.26

As the 1913 season wound to a close for the third-place Cubs, manager Johnny Evers matched Zabel in an offday exhibition game against his regulars. Surprisingly, the “young collegian made monkeys”27 of the first-stringers, setting them down on five hits, 4-1.28 Impressed, Evers sent Zabel back to the mound the next day (October 5, 1913) to make his major-league debut against the Pittsburgh Pirates. The result: five innings of three-hit, shutout pitching, with the youngster getting credit for the Cubs’ 5-1 victory. After the game, Cubs owner Charles Murphy declared that he “wouldn’t take $20,000 for George Zabel,”29 while Evers subsequently opined that “after seeing Zabel pitch against our regulars and the Pirates, I am firmly convinced that he is a star of the first quality.”30 Zabel was immediately signed for the 1914 season. Chicago expected great things from him, but again school would come first. That fall, George returned home to continue his college studies, but gave up football. His athletics were confined to captaining the Baker Methodists basketball team.

Over the winter, Zabel rejected overtures from the upstart Federal League.31 But as had now become his custom, George did not report for duty until the 1914 season was already well under way. Given a late-May start by new Cubs manager Hank O’Day, Zabel turned in a creditable performance against the New York Giants but dropped a 3-1 decision to pitching master Christy Mathewson. He won his second start, but then began to experience arm miseries, likely a legacy of the profligate way that he had been used during his college and semipro days. Whatever the cause, a visit to the celebrated Bonesetter Reese was deemed to have cured the problem.32 Used sparingly thereafter, Zabel won three late-season games to finish 4-4, with an excellent 2.18 ERA in 128 innings pitched for the fourth-place (78-76) Cubs.

After leading Baker to the 1914-1915 Kansas Conference basketball title over the winter,33 Zabel joined the Cubs in time to see some early-season duty for latest club manager Roger Bresnahan. By the first week in June his record stood at 4-4, with shutouts hurled in three of those victories. On June 17, George was not expected to see action in a home game against Brooklyn. But in the top of the first, a wicked Zack Wheat smash through the box caught Chicago starter Bert Humphries square in the pitching hand and knocked him out of commission. Rushed into action without much warm-up, Zabel escaped without further damage when Brooklyn baserunner George Cutshaw was picked off third. The Cubs promptly notched two in their half of the inning, and Zabel nursed a 2-1 lead into the eighth, only to see a Chicago fielding miscue allow the tying run to score. He and Brooklyn starter Jeff Pfeffer then matched blanks until the 15th, when shoddy defensive work on both sides raised the score to 3-3. Finally, after Zabel had retired the Robins in the top of the 19th inning, an errant throw by second baseman Cutshaw plated the clincher in the Cubs’ 4-3 win. In his major-league record-setting relief appearance, Zabel had pitched 18⅓ innings, allowing two unearned runs on nine hits. He had struck out six, while walking only one. Hard-luck loser Pfeffer, meanwhile, had gone the distance.

Although only 24 years old, George Zabel was never quite the same after his marathon outing. He lasted only two innings in his next start, and was soon complaining of a sore arm.34 The stage was now set for the most humiliating episode of Zabel’s major-league career. With the club mired in mid-pack in the National League pennant chase and manager Bresnahan losing control of his charges, the Cubs faced the league-leading Philadelphia Phillies on July 20. After starter Jimmy Lavender was lifted for a pinch-hitter, Bresnahan brought in Zabel to pitch the bottom of the seventh with the score tied 2-2. Zabel walked the leadoff batter, but then retired the next three in order, leaving the game deadlocked. With a three-run rally having put the Cubs in the lead, George returned to the mound in the eighth and got the first batter out. He walked the next. With one on and one out, Bresnahan “in a towering rage … ordered Zabel from the hill and replaced him with [lefty George] Pierce.”35 A comedy of hits, errors, wild pitches, and pitching changes ensued, yielding the six-run rally that keyed the Phillies’ eventual 8-6 victory.

Postgame commentary skewered Bresnahan for his panicky pitching switches,36 but Roger saw the game outcome as just the latest manifestation of poor player conditioning and bad attitudes. He then set about rectifying the situation by making examples of two Cub players. The sanctioning of chronic malcontent Heinie Zimmerman, fined $25 for failure to run out a groundball, was unremarkable. But the $100 fine and indefinite suspension imposed on the quiet, mannerly George Zabel seemed inexplicable. According to Bresnahan, the pitcher (who had tuned in a record-long relief effort only the previous month) lacked stamina and was out of condition.37 Zabel was, therefore, banished to Chicago under orders to throw twice a day until he was back in condition to pitch.38 Engaging a catcher at his own expense, Zabel dutifully complied with his manager’s edict, hoping to work himself back into Bresnahan’s good graces. He was also hopeful that the $100 fine would be remitted. Zabel was living on modest salary, and responsible for the tuition needed to complete his degree at Baker University, as well.39 In time, George was restored to the Cubs roster, but made only spot appearances from there on. At season’s end, his 7-10/3.20 ERA record was only slightly below the norm for the fourth-place (73-80) 1915 Chicago Cubs.

Final winter-term exams delayed Zabel’s arrival at the Cubs’ 1916 spring camp in Tampa, where yet another new manager, recently retired shortstop Joe Tinker, had taken charge. Impatient, Tinker had imposed $100 fines on Zabel and outfielder Frank Schulte for their tardiness, but rescinded the Zabel sanction upon being advised that George would have lost credit for the semester’s work if he had skipped his finals.40 But Zabel did not fit in Tinker’s plans and before the Cubs broke camp, he was optioned to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.41 Pitching for future Hall of Famer Frank Chance, George turned in a solid 17-13/2.38 ERA campaign for the pennant-winning (119-79) Angels. But the important events in life occurred away from the diamond. In June he married college sweetheart Ruby Kress, commencing the 54-year marriage that would last the rest of his life.42 The year also saw his graduation with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Baker University.43 With these developments, playing major-league baseball receded in importance to George Zabel.

Chance was anxious to have Zabel return to the Angels for the 1917 season, but latest Cubs manager Fred Mitchell had a fondness for large right-handed pitchers and brought Zabel to the Cubs’ spring camp.44 George remained on the Chicago roster in the early going but saw no game action.45 Then, much to Chance’s chagrin, the Cubs sold Zabel to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League.46 Thus ended the major-league career of George Zabel. In 66 games, all with the Chicago Cubs, he had gone 12-14 (.462), with a solid 2.71 ERA. In 296 innings pitched, Zabel surrendered 231 base hits, striking out 110 while walking 130.

Zabel, an excellent cold-weather pitcher, got off well with Toronto, registering 10 wins before June was up. That performance rekindled major-league interest in the still youthful (26) hurler, but George was now intent on a new career. In early July, he abandoned the Maple Leafs to join the unfortunately-named Beloit Fairies, the nine entered into the highly competitive Chicago City League by the Fairbanks-Morse Company, a large machinery manufacturer headquartered in Beloit, Wisconsin.47 But unlike others flocking to defense industry ballclubs to avoid military service in World War I, Zabel was not your standard company rent-a-jock. He was a budding scientist whose newly-minted chemistry degree could be put to good use in Fairbanks-Morse laboratories.48

For the next decade, George satisfied his passion for sport by playing baseball, basketball, and, occasionally, tennis on company teams. At the same time, he rose in stature in the company hierarchy and in the scientific community. By 1926, Zabel had risen to chief metallurgist at Fairbanks-Morse.49 He would later become superintendent of company foundries, nationwide. George was also active in the American Society for Steel Testing, an industry educational association, and a frequent lecturer on scientific subjects. By the 1940s, his research on electric plating and spectrograph analysis had earned Zabel an entry in Who’s Who in the Midwest.50 He retired from Fairbanks-Morse in 1948, and subsequently entered public service. In 1958, Zabel was elected to the first of his five terms to the Rock County (Wisconsin) Board of Supervisors. He also served a term on the Beloit City Council.51

On May 31, 1970, George Washington Zabel died at Beloit Memorial Hospital. He was 79. Following funeral services, his remains were interred at Mt. Thabor Cemetery, Beloit. Survivors included his wife, Ruby; children, Kathryn and John Stanley; and three grandchildren. Remembered today, if at all, for an inapt nickname and one record-setting June 1915 afternoon on the pitching mound, George Zabel led a long, interesting, and productive life.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail contained herein include the Zip Zabel file with questionnaire maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Zabel family info posted on Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Undated George W. Zabel questionnaire on file at the Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown.

2 His older brothers were Charles (1884-1963) and David (1885-1965).

3 According to the self-completed Zabel questionnaire on file at the Giamatti Research Center. Retrosheet lists Zabel at 6-feet-1½/185 lb., while Baseball-Reference puts him at 6-feet-1”/185 lb.

4 As subsequently related by Zabel himself in the Grand Forks (North Dakota) Evening Times, March 4, 1914. At the time, the “two-year rule in college athletics” made Zabel ineligible to play for Kansas in 1910-1911. But a profile of Zabel by Chicago Tribune sports editor Harvey Woodruff posited that KU had deemed Zabel ineligible for playing semipro baseball the previous summer. See Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1914.

5 Founded in 1858 by the United Methodist Church, Baker University is the oldest four-year college in Kansas.

6 As per the Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1914, which stated that Zabel was paid $100 per month.

7 Denver Post, October 21, 1911.

8 Ibid.

9 According to the Denver Post, July 16, 1911.

10 Prior to an important clash with Denver University, a photo of fullback Zabel and his Baker teammates was published in the Denver Post, October 21, 1911. As per local conference rules, however, Zabel and three other Baker freshman standouts were not permitted to suit up for games against in-state rivals Emporia, Fairmount, and the Kansas State Aggies. See the Kansas City Star, November 7, 1911.

11 Zabel was described as “a power on defense” for Baker in a 32-31 loss to undefeated Emporia College by the Emporia (Kansas) Gazette, March 2, 1912.

12 As reported in the Kansas City Star, March 12, 1912.

13 As noted in the Kansas City Star, March 12, 1912, Houston Chronicle, April 8, 1912, and Sporting Life, May 11, 1912.

14 Emporia Gazette, April 26, 1912. Zabel struck out 17 Missouri Normal batters in the process.

15 See, e.g., the Kansas City Star, January 13, 1914.

16 Using ProQuest, the writer’s survey of the first 40 mentions of the Zabel name in the Chicago Tribune yielded the following results: George Zabel 14 times; Zabel, with no first name given, 13 times; George Washington Zabel/G. Wash Zabel 12 times; Zip Zabel once. As a descriptive for Zabel, Tribune sportswriters favored “our young chemist from Kansas,” or the like.

17 Interestingly, the original 1951 edition of Turkin and Thompson’s Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, a frequent font of error on player biographical detail, listed our subject as George Washington Zabel, without a nickname.

18 As noted in the Kansas City Star, June 11, 1912.

19 As reported in the Kansas City Star, June 11, 1912, and Sporting Life, June 22, 1912.

20 As subsequently reported in Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1914.

21 Compare the Grand Forks Evening Times, March 4, 1914: blood poisoning, with the Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1914: delivery tinkering.

22 As noted in Sporting Life, June 21, 1913. It had earlier been reported that Zabel was sold to Helena (Montana) of the unrecognized Union Association. See, e.g., the Kansas City Star and Salt Lake Telegram, June 6, 1913, and Sporting Life, June 14, 1913.

23 According to Zabel in the Grand Forks Evening Times, March 4, 1914. Louisville’s subsequent return of Zabel to Kansas City was reported in the Kansas City Star, July 6, 1913, and Sporting Life, July 19, 1913.

24 As reported in the Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, July 7, 1913, Philadelphia Inquirer, July 8, 1913, and elsewhere.

25 As per the Duluth News-Tribune, September 28, 1913.

26 As reported in the Charleston Evening Post and (Boise) Idaho Statesman, September 12, 1913.

27 See the Cincinnati Post, Kansas City Star, and Springfield (Massachusetts) Daily News, October 6, 1913.

28 As reported in the Chicago Tribune, October 4, 1913.

29 As per the Cincinnati Post, Kansas City Star, and Springfield Daily News, October 6, 1913.

30 Grand Forks (North Dakota) Daily Herald, October 21, 1913.

31 Baltimore Federals manager Otto Knabe had publicly set his sights on Zabel, as reported in the Grand Forks Daily Herald, January 13, 1914, and Sporting Life, January 17, 1914. Later, former minor-league manager John “Mickey” Malloy filed suit against the Cubs seeking $2,000 for services rendered on the club’s behalf regarding its retention of Zabel and first baseman Fritz Mollwitz. See the Rockford (Illinois) Register-Gazette, April 14, 1914, and Sporting Life, May 2, 1914. The outcome of the Malloy suit is unknown.

32 As per Sporting Life, July 4, 1914.

33 Following a 33-26 Baker victory over Emporia College, the often-unfriendly Emporia Gazette declared that Zabel “played a remarkable game [and] was the whole Baker team.” Emporia Gazette, February 5, 1915. Unusual for its time, the Baker five was also integrated, with “Wright, the colored forward,” a valuable member of the squad. See the Emporia Gazette, January 5, 1915.

34 As reported in the Grand Forks Daily Herald, July 13, 1915.

35 The Jersey (Jersey City) Journal, July 22, 1915.

36 Normally genial Philadelphia sportswriter Jim Nasium (Edgar Forrest Wolfe) sub-captioned his game account: “Scored 6 Runs in 8th, Greatly Aided and Abetted by Bresnahan’s Manhandling of His Own Pitchers, Turning Apparent Defeat into Unexpected Victory,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 21, 1915.

37 As reported in the Washington Evening Star, July 22, 1915.

38 The discipline was widely reported. See, e.g., the Kansas City Star, July 22 and August 5, 1922, Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times, July 22, 1915, and Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, July 23, 1915.

39 As per the Kansas City Star, August 5, 1915.

40 As per the Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1916. Remission was contingent upon Zabel’s passing his exams, which he did. Had Zabel flunked any of them, Tinker maintained, the $100 fine would have stuck.

41 As reported in Sporting Life, March 25, 1916.

42 As reported in the Emporia Gazette, June 5, 1916, and Denver Post, June 17, 1916. The bride, originally from Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, was a year behind George at Baker University.

43 As noted in the completed Zabel questionnaire at the Giamatti Research Center.

44 Mitchell had Cubs owner Charles Weeghman rescind Zabel’s tentative transfer to Los Angeles. The new Cubs skipper wanted a firsthand look at Zabel in spring camp, reported the Washington Evening Star, February 25, 1917.

45 Zabel’s presence with the Cubs during games played in Pittsburgh in late April 1917 was noted by The (Portland) Oregonian, April 24, 1917.

46 As reported in The Oregonian, May 12, 1917.

47 As reported in the Rockford (Illinois) Republic, July 6, 1917, and Salt Lake Telegram, July 7, 1917.

48 By the time he registered for the draft, Zabel, with a wife and infant daughter to support, was an unlikely conscription candidate.

49 As noted in the Rockford Republic, July 12, 1926.

50 As per the Janesville (Wisconsin) Daily Gazette, March 5, 1966, which published a résumé of Zabel’s civic and scientific accomplishments when he stood for re-election as a county supervisor.

51 As per Zabel’s obituary published in the Beloit (Wisconsin) Daily News, June 1, 1970.

Full Name

George Washington Zabel

Born

February 18, 1891 at Wetmore, KS (USA)

Died

May 31, 1970 at Beloit, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.