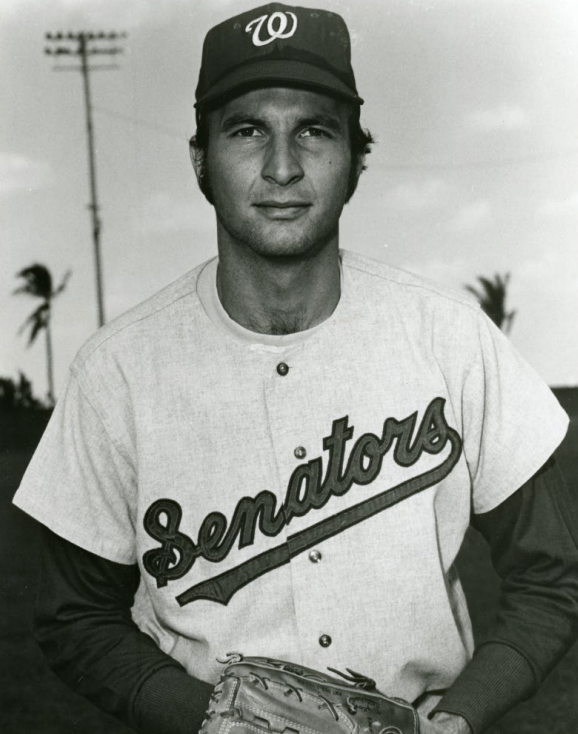

Gerry Janeski

In his April 27, 2014, major-league debut, righty Scott Carroll tied the Chicago White Sox record for the longest initial outing by one of its pitchers: 7⅓ innings, last established by Gerry Janeski in 1970. After a dubious start to his major-league career – four hits and a hit-by-pitch to his first six batters – Janeski settled down to surrender just one run in his next 20⅓ innings. Buried in the Boston Red Sox organization for five years, Janeski’s 2-0, 1.65 mark in his first two big-league appearances, including a three-hit shutout over the Oakland Athletics, drew instant attention. Not an overpowering pitcher, Janeski prided himself on his control. “I pitch low, the sinker,” Janeski explained. “I try to make them hit the ball into the ground.”1

In his April 27, 2014, major-league debut, righty Scott Carroll tied the Chicago White Sox record for the longest initial outing by one of its pitchers: 7⅓ innings, last established by Gerry Janeski in 1970. After a dubious start to his major-league career – four hits and a hit-by-pitch to his first six batters – Janeski settled down to surrender just one run in his next 20⅓ innings. Buried in the Boston Red Sox organization for five years, Janeski’s 2-0, 1.65 mark in his first two big-league appearances, including a three-hit shutout over the Oakland Athletics, drew instant attention. Not an overpowering pitcher, Janeski prided himself on his control. “I pitch low, the sinker,” Janeski explained. “I try to make them hit the ball into the ground.”1

But control problems contributed to Janeski’s early exit from the majors when, inexplicably, his walks-per-inning ratio nearly doubled during his sophomore season. Though he found some later success as a reliever (particularly after returning to the minors) Janeski never rebounded to the majors after four brief appearances in 1972.

Gerald Joseph Janeski was born on April 18, 1946, the younger of two children of Joseph Francis and Stanistawa C. “Sophia” (Grygier) Janeski, in Pasadena, California. He was the grandson of Polish and German immigrants, the paternal surname shortened from Janiszewski by his father.2 Gerald and his sister attended La Salle High School in Pasadena, a private institution founded in 1956 in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles. The La Salle Lancers established their first varsity baseball team in 1959. During his junior and senior years (1963-64) Gerry Janeski, under the guidance and no-nonsense approach of baseball coach Phillip “Duffy” Lewis, was named as a pitcher to the Santa Fe All-League first team. Janeski moved on to nearby California State University Los Angeles, where the English major3 honed his talent under the watchful eye of famed Golden Eagles baseball coach Jim Reeder. It was from these collegiate fields that scout and former major-league catcher Joe Stephenson signed Janeski to a Boston Red Sox contract in 1965.

Janeski was assigned to the Waterloo (Iowa) Hawks in the Midwest League (Class A). In the pitching-dominant circuit, the 19-year-old made a strong professional debut: eight wins and a 2.56 ERA in 16 appearances (league average: 3.21). When the season ended Janeski was named the Hawks’ most valuable pitcher. Excepting a brief stint in the Double-A Eastern League in 1966, Janeski bounced among the organization’s varied Class-A affiliates the next two years. Personal highlights included a 13-strikeout venture on June 30, 1966, against the Dubuque Packers – believed to be a single-game career high – and a heartbreaking 1-0 loss to the Greensboro Yankees in 1967 in which Janeski retired 21 consecutive batters before surrendering a ninth-inning homer. While pitching for Winston-Salem in the Carolina League in 1967, Janeski placed among the league leaders in ERA for portions of the season until a second-half dip took him out of the running. He still finished well below the league average with a 2.95 mark.

Greater success came in 1968 in Janeski’s second stint in Pittsfield, Massachusetts (Double A): 7-3, 1.32 in 15 appearances. In June the Louisville Colonels’ Ken Brett, the Red Sox’ prized lefty prospect, was shelved with what was feared to be a career-threatening elbow injury. The organization promoted Janeski to Louisville as Brett’s replacement on the Triple-A roster. Used exclusively in relief, Janeski was challenged when he did not have time to loosen properly. “Usually it takes me an inning or two to get loose,” Janeski confessed (though he did co-author a June 21 shutout over the Syracuse Chiefs).4 When Brett recovered sufficiently to rejoin the Colonels, Janeski was sent back down. He won five straight games to lead Pittsfield’s effort to overtake the slumping Reading Phillies and capture the league flag. In September the two teams competed in the championship playoffs. Janeski got his team’s only series win, a 2-1 contest in which the righty scored the winning run in the 10th inning.

Reassigned to Louisville in 1969, Janeski set an early tone for his finest professional campaign with a shutout of the Toledo Mud Hens on April 28. One month later he impressed teammate Bob Montgomery with a two-hit shutout over the hard-hitting Tidewater Tides: “I could have caught Janeski in a rocking chair today,” the batterymate joked. “He was so relaxed that I thought we might have to go out and wake him up a couple of times.”5 On July 14 Janeski became the first 12-game winner in Triple A. He was selected as the International League’s starter in the August 7 All-Star tilt against the Washington Senators. In Tidewater manager Clyde McCullough’s plan to use one pitcher per inning in the circuit’s midsummer classic, Janeski needed just eight pitches in the first frame to dispose of the Washington batters. As Louisville manager Eddie Kasko explained, “Janeski looks good to hit. The hitter likes what he sees but, when the ball gets to the plate, the bottom drops out of it.”6 The durable hurler finished the season with an International League-leading 14 complete games while placing among the leaders in wins (15), innings pitched (186), shutouts (3), and walks per nine innings (1.7).7 Though the parent club struggled from the mound in the 1969 campaign, there is no evidence that the Red Sox considered promoting Janeski during the season (though he was placed on the 40-man roster during the offseason).

In 1970 Janeski reported to the club’s Winter Haven, Florida, spring camp. He shared a passion for kite flying with slugging prospect Billy Conigliaro, oblivious to the ongoing negotiations of a December 13, 1969, four-player swap between Boston and the Chicago White Sox. Minor-league pitcher Billy Farmer had refused to report to the White Sox and the teams sought a suitable replacement. On March 9 the clubs agreed upon Janeski. The previous year the White Sox were spared the league’s worst pitching solely by the existence of the expansion Seattle Pilots. Little improvement was expected in 1970 when, with reference to veteran starters Tommy John and Joe Horlen, the phrase heard often around Chicago’s Sarasota, Florida, camp was “Tommy and Joe and pray for snow.”8 Three innings of shutout ball by Janeski against the Detroit Tigers on March 14, followed eight days later by four innings of the same against Kansas City, attracted much attention. “I think we’ve got a pitcher there,” said manager Don Gutteridge. “The more I see of him, the more I like him. … he has good poise.”9 The Chicago scribes fawned on him as well, describing Janeski as “quite a refreshing sort … intelligent and articulate.”10 On April 1 Janeski’s fate was sealed with a “standout performance”11 against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He was provided an opportunity to continue flying kites in the Windy City when he accompanied the club to Chicago as the White Sox’ number-three starter.

An Opening Day 12-0 thumping by the Minnesota Twins accented the plight of the White Sox’ 1970 campaign. A season-long mediocre offense, coupled with the majors’ worst ERA, contributed to a 106-loss season (a franchise worst through 2017). Janeski’s debut performance was the club’s first win of the season, and a successful 5-2 run beginning May 12 provided the rookie with a team-leading seven victories. This included a strong June 9 outing against the organization that had buried him for so many years (a two-run homer by future Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski was the only barrier between the hurler and his second career shutout). Eight days later Janeski, at best a fair hitter, helped his own cause by driving in three runs on a single and a squeeze bunt to corral the New York Yankees, 6-3. He lacked run support in what might have been two additional wins.

Another attribute that made Janeski popular with the sportswriters was his keen sense of humor. In his first 60⅔ innings, Janeski surrendered just two home runs, both three-run shots by Baltimore slugger Boog Powell, who was on his way to his only MVP season. After the second blow, Powell “said Janeski was a very impressive pitcher ‘and throwing harder’ than the first time. The righty retorted … ‘If I throw any harder, he’ll hit it to the moon.’”12 Dubbed a “sensational rookie”13 by reporters, Janeski drew favorable comparisons to fellow first-year players Thurman Munson and Bert Blyleven.

But hitters started to zero in on the rookie hurler. Beginning on June 27, Janeski won just one of 11 decisions as his ERA approached five. Pitching coach Les Moss began working with Janeski on a slip pitch. “He has a good fastball and slider,” Moss explained. “But he’s been around the league twice now and everyone knows that’s all he can throw. It’s time for him to develop a pitch to fool some people.”14 The additional instruction took. Excluding an August 30 outing against Boston – a game in which no pitcher was spared as the teams combined to score a near-record 32 runs – Janeski finished the season 2-2, 3.22 over his last six appearances. He concluded the year among the team leaders in appearances (35), innings pitched (205⅔), wins (10), and losses (17) to earn White Sox’ Rookie of the Year honors.

Under the watchful eye of Johnny Sain, the White Sox’ new pitching coach, Janeski ventured south where he played for the Zulia Eagles in the Venezuelan Winter League. The experience proved challenging for Janeski as he performed poorly under Eagles manager Luis Aparicio. The White Sox began shopping the hurler. On February 9, 1971, Janeski was traded to the Washington Senators for outfielder Rick Reichardt.15 Janeski’s arrival, combined with the earlier acquisition of former 30-game winner Denny McLain, caused manager Ted Williams to gush, “We just might have the best pitching in the American League.”16

The only thing the Splendid Splinter knew about pitching was how to hit it. Grand expectations fell far short as the 1971 Senators plunged to their annual second-division finish; the staff in general, and Janeski in particular, realizing their own challenges. Janeski’s trials began in spring training when a brilliant outing was often balanced against a less distinguished one. Williams vacillated between plugging Janeski into the rotation and using him in relief. The manager’s mind was made up on April 2 when the Atlanta Braves pummeled the righty for 13 hits and seven runs in five innings.

In his first nine relief appearances, Janeski pitched brilliantly: nine hits and one run surrendered over 10⅔ innings (there were two less successful starts). On April 21 he earned what became his last major-league win with 2⅔ innings of two-hit relief against the Yankees in New York. Williams’s confidence in Janeski grew and he inserted the righty into the rotation. Despite a high walk yield and two losses, Janeski made an adequate showing (3.64 ERA) in five starting assignments through June 9. Far less success ensued. He did not survive the second inning in a start against the Baltimore Orioles on June 22. Five days later, Williams used a quick hook in New York after Janeski walked the first two batters. The righty was optioned to the Triple-A Denver Bears after a June 29 relief appearance against the Red Sox.

Janeski earned four wins, including an August 15 shutout over the Tulsa Oilers, to lead the Bears to a first-place finish in the West Division of the American Association. But his bigger contributions came in the playoff series that followed. On September 9 manager Del Wilber turned to Janeski in the decisive Game Seven for the league championship against the Indianapolis Indians. The righty hurled a five-hit complete-game victory (surrendering no earned runs) to advance the Bears to the Junior World Series. A week later he was just as effective against the Rochester Red Wings: a 3-2 complete-game win in which Janeski induced 19 outs via infield grounders. But the string of playoff success ran out when Wilber again turned to Janeski for a Game Seven win to no avail.

Janeski enjoyed continued success in Denver in 1972 after a dreadful spring training. On April 18 he fired a five-hitter against Tulsa in a 3-2 win, then two weeks later pitched a three-hit victory over Indianapolis. Placing among the league leaders at 4-1, 2.72, he earned promotion to the parent club (relocated to Texas) when rookie reliever Don Stanhouse was injured. Janeski made four appearances, including a strong start in a losing effort against the White Sox on May 23. But the healthy return of Stanhouse, combined with the acquisition of infielder Dalton Jones from Detroit, caused a roster logjam. Janeski made what turned out to be his last major-league appearance on May 28, 1972 (a successful two innings of relief against the Twins), before being optioned back to Denver. Encumbered by a second-half swoon, he finished the Triple-A season with a record of 11-10, 4.79.

With the exception of one starting assignment in 1973, Janeski concluded his professional career from the bullpen. Pitching for the Spokane Indians in the Pacific Coast League (the Rangers’ newly located Triple-A affiliate) Janeski began a brilliant 1973 campaign (4-1, 1.89, and a league-leading 14 saves) before suffering another second-half swoon. Postseason success was again realized on September 6 when Janeski captured the win in relief in the last of a three-game sweep over the Tucson Toros to capture the league championship. In May 1974, Janeski moved to the San Diego Padres’ Hawaii affiliate, where once again a strong start yielded to a second-half swoon (1-3, 5.63 in his last 26 appearances). The disappointing finish convinced Janeski to seek other endeavors.

During the major leagues’ 1970 All-Star break, Janeski married Suzanne Virginia “Suzie” Prater. A native of Alhambra, California (Los Angeles County), Suzie’s spent her childhood in close proximity to the Pasadena haunts of Janeski’s youth. The couple returned to California, where Janeski (joined later by his wife and son) launched a successful career in real estate. In the 1980s he formed an investors group with Hall of Famer Hank Greenberg. Throughout this time Janeski was active alongside fellow major-league alumni in a campaign to ensure financial assistance to players who found far less success after baseball. The campaign realized success in 2011 when Commissioner Bud Selig announced that the new Collective Bargaining Agreement would include annual annuities up to $10,000 to baseball’s “lost boys.”

In 62 major-league appearances (280 innings) Janeski earned 11 wins against 23 losses and a 4.73 ERA. Bypassed and seemingly ignored for five years in the Boston Red Sox organization, he defied the odds by emerging on the big-league scene with a splash. His inability to master more than a terrific slider and pedestrian fastball, combined with the inexplicable control problems encountered after his rookie season, stymied what might have been a much longer career.

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, and the following websites:

baseballlibrary.com/ballplayers/player.php?name=Gerry_Janeski_1946.

knightfever.wordpress.com/2015/08/18/knights-knotes-august-17-2015/.

lasallehs.org/s/639/start.aspx.

lancerbb.org/La_Salle_Lancers_Baseball/History.html.

ocweekly.com/2012-03-29/news/major-league-baseball-players-medical-pension-richard-lee-dick-baney/.

realtor.com/realestateagents/Jerry-Janeski_Laguna-Niguel_CA_49384_965894497.

The author wishes to thank Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 “Janeski in Control,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1969: 42.

2 Though they lived just 40 miles apart in Pennsylvania in the 1930s, the author was unable to make any familial ties between Gerald’s father and minor-league player Robert J. Janeski (baseball-reference.com/register/player.cgi?id=janesk001rob).

3 An avid reader, Janeski was particularly fond of author John Steinbeck.

4 “American Assn.,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1971: 36.

5 “International League,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1969: 34.

6 “International League,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1969: 38.

7 On the downside, Janeski also led the league with 218 hits surrendered.

8 This echoed a popular tagline from the Boston Braves’ 1948 pennant run: “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” (sometimes rendered as “Spahn and Sain and two days’ rain.”)

9 “Chisox ’70 Chant: ‘Tommy and Joe – Pray for Snow,’” The Sporting News, April 4, 1970: 8.

10 Ibid.; A health enthusiast, Janeski earned the nickname The Wheat Germ Kid when reporters noticed that his locker resembled a health-food store.

11 “Exhibition Games,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1970: 35.

12 Nothing Chilly About Mac’s Chisox Bat,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1970: 21.

13 Ibid.

14 “Major Flashes,” The Sporting News, August 15, 1970: 30.

15 Reichardt, acquired by the Senators just the year before, appears to have rankled feathers in a salary dispute that precipitated his early exit from Washington.

16 “Denny Wins Gold Star as First-Week Nat,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1971: 39.

Full Name

Gerald Joseph Janeski

Born

April 18, 1946 at Pasadena, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.