Gil Hatfield

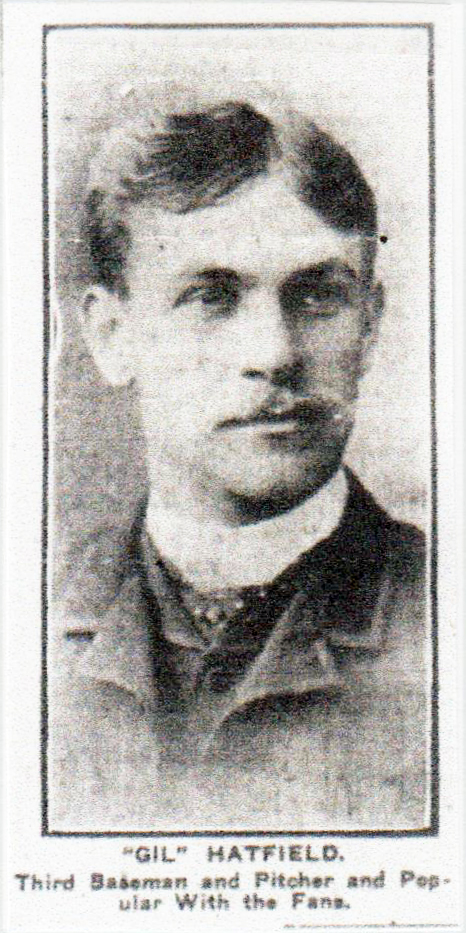

Had he possessed the batting ability of his older brother John, Gil Hatfield might well have become a late 19th-century major league star. A natural athlete, Gil was blessed with good hands, a strong and accurate throwing arm, ample foot speed, and an abundance of baseball smarts. On top of that, he was both versatile – able to pitch and to man every defensive position save catcher – and durable, rarely, if ever, sidelined by injury. Moreover, and here he was unlike his brother, Gil Hatfield was a man of sterling character: sober, modest, affable, and even-tempered. Nevertheless, weakness with the stick relegated him to utilityman status; only once in his eight-season career as a big leaguer was Hatfield an everyday player. Yet his passion for playing the game was unquenchable, keeping him active on semipro and amateur diamonds into his early 50s. The paragraphs below recall the life of this baseball diehard from yesteryear.

Had he possessed the batting ability of his older brother John, Gil Hatfield might well have become a late 19th-century major league star. A natural athlete, Gil was blessed with good hands, a strong and accurate throwing arm, ample foot speed, and an abundance of baseball smarts. On top of that, he was both versatile – able to pitch and to man every defensive position save catcher – and durable, rarely, if ever, sidelined by injury. Moreover, and here he was unlike his brother, Gil Hatfield was a man of sterling character: sober, modest, affable, and even-tempered. Nevertheless, weakness with the stick relegated him to utilityman status; only once in his eight-season career as a big leaguer was Hatfield an everyday player. Yet his passion for playing the game was unquenchable, keeping him active on semipro and amateur diamonds into his early 50s. The paragraphs below recall the life of this baseball diehard from yesteryear.

In many respects, Gilbert Hatfield did not fit the 19th-century baseball player mold. For one thing, he was not the typical poor man’s son who saw the game as a means of escaping the drudgery of farm work, coal mining, or factory labor. To the contrary, Hatfield came from a prominent and well-to-do family. He was born on January 27, 1855, in Hoboken, New Jersey, then a bucolic enclave of the upper crust. Father James Thomas Hatfield (1819-1893) was a prosperous local businessman-politician known as “General Hatfield.”1 Mother Mary Jane (née Van Buskirk, 1821-1858) descended from Knickerbocker patroons.2 The considerable Hatfield family fortune was amassed by the grandfather for whom our subject was presumably named: Gilbert T. Hatfield (1791-1880), a successful dry goods merchant turned shipbuilder. By the time of Gil’s birth, grandfather Hatfield was reputedly the wealthiest man in Hoboken and one of the surrounding county’s largest landowners.3

Young Gil and his three siblings were raised in a luxurious brownstone complete with servants.4 He was educated in local classrooms before being shipped off to the Pennington School, an elite Methodist Church-affiliated boarding academy located just north of Trenton. There, he completed his secondary schooling. By that time, brother John Hatfield (eight years older) had already made a name for himself as a cricket and baseball player. In 1868, the elder Hatfield joined the juggernaut nine that Harry Wright was assembling in Cincinnati. However, he left the club the following spring amidst a swirl of accusations of fraud, embezzlement, passing bad checks, running out on debts, and contract jumping. Unperturbed, John Hatfield, a heavy hitter with a prodigious throwing arm,5 went on to post a pair of standout seasons with the New York Mutuals of the National Association, baseball’s first professional league. Meanwhile, Gil was reported to be attending Yale6 (although no evidence corroborating his matriculation there was found by the writer).

Also unconventional was the route that Hatfield took to the majors. The details of just how he got started in the game are lost, but presumably he began playing sandlot baseball at Hoboken’s Elysian Fields, situated only a long fly ball away from the Hatfield residence, and worked his way up from there to local amateur clubs.7 But when he completed his schooling, Gil did not attempt to make a living from baseball. Instead, he took an office job with the retail pioneer R.H. Macy and Company in New York City.8 He continued playing amateur ball, however, during his free time.9

In spring 1883, Gil Hatfield finally entered the professional ranks at the advanced age of 28, joining a reserve nine fielded by the New York Metropolitans of the major league American Association.10 For the Mets reserves, originally based in Newark and thereafter removed to Hartford,11 the versatile Hatfield played first base, second base, and the outfield, and pitched on occasion.12 At season’s end, his batting average stood at .255 in 82 games, and it was reported that he was signed by the parent club for the following year.13

Notwithstanding the reported pact with the Mets, Hatfield began the 1884 season with the Baltimore Monumentals of the newly formed minor Eastern League.14 When the Monumentals folded three weeks into the season, Gil joined another EL club, the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Olympics, primarily as a first baseman. The failure of the Harrisburg franchise in early July led to his engagement by a third Eastern League club, the Newark Domestics.15 Late in the campaign, the Domestics traveled to Hartford for an exhibition game against a local semipro team. And there for the only time in his life, Hatfield was accused of untoward conduct.

According to Hartford nine manager Charles Soby, the previous summer Hatfield and a teammate named Miesel had assumed operation of a local cigar shop owned by Soby, but had not compensated him for $700 in shop merchandise. Soby therefore had the two arrested on a fraud charge when they arrived in town but consented to their release without bond upon Hatfield’s promise of recompense.16 The complainant, however, was left without redress when Hatfield and Miesel left Hartford without settling their debt.17 No further information about the incident was uncovered; today in retrospect the Soby allegations seem so out of character for Gil Hatfield as to be inexplicable, if true. Whatever the actual facts of the case, Hatfield finished the season with Newark, regarded as the best hitting third baseman in the Eastern League.18

Gil returned to Newark for the 1885 season, but his batting average plummeted to a paltry. 207 in 83 games. Released by the Domestics, Hatfield was playing for the semipro Jersey Blues when the National League’s Buffalo Bisons arrived in New York for a late September series against the Giants. With third baseman Deacon White ailing, Davy Force was moved over from second to cover the hot corner. Hatfield was engaged to fill the infield void, at least temporarily. On September 24, 1885, 30-year-old Gil Hatfield, “brother of old ‘Jack’ Hatfield, the celebrated long-distance thrower,” made his major league debut at the Polo Grounds.19 A right-handed batter, Hatfield began impressively, going 2-for-3 with a triple off future Hall of Famer Tim Keefe and handling four fielding chances cleanly in an 11-3 Buffalo loss. But he could not keep it up, registering only two more base hits in his next 27 at-bats and striking out 11 times. Gil also made six defensive errors at second and third base in 11 games played. Not unsurprisingly, he was jettisoned by Buffalo at season’s end.

Despite his age and the failure of his audition with Buffalo, Hatfield persisted in his pursuit of a career in professional baseball. Landing a job for 1886 with the Portland (Maine) entry of the New England League,20 he reestablished his prospects over the next two seasons. Stationed mostly at third base and batting fourth in the lineup, Gil helped Portland (66-36, .647) cruise to the league title in his first campaign there.21 Before beginning his second year in Portland, however, he entered a long-term engagement of a different kind back home, marrying Hoboken school teacher Grace Child.22 In time, the birth of daughters Grace and Ruth completed the family.

Hatfield had a superb second season with runner-up Portland (68-36, .654) in 1887. In 103 games played, he posted an eye-catching .339 batting average23 and led the New England League in stolen bases with 141. Used as a spot starter, right-hander Hatfield also turned in excellent hurling numbers, going 8-4 with a sparkling 1.84 ERA in 117 1/3 innings pitched. Deemed “possibly the best all around player in the NEL,”24 Hatfield was acquired in mid-September by the New York Giants.25

He returned to the bigs on October 7, hitting a late-game RBI single that enabled the Giants to salvage a 5-5 tie against Philadelphia. The following day, he chipped in another RBI single in a season-ending loss to the Phillies, 6-3. In all, he went 3-for-7 with three RBIs, and accepted eight chances at third base without an error, creating in the process “a very favorable impression” on the club’s New York Times correspondent.26 Sporting Life was also a booster, but commented that “the chief drawback to young Hatfield’s future in the league is a lack of self-confidence.”27

The revelatory feature of the above quotation is the use of the adjective “young.” Although Gil made no known effort to camouflage his date of birth or to conceal that he was the brother of a ballplayer from the Pioneer Era, the sporting press labored under the chronic misapprehension that Hatfield was a youngster. Presumably, the press was misled by the brevity of his career as a minor leaguer and by his youthful appearance. A 32-year-old when he joined the Giants, Hatfield was a handsome, well-proportioned man (5-foot-9, 168 pounds) who always remained in peak physical condition. During much of his playing career, he benefited from simply looking much younger than he actually was, and it took some years for the press to get wise to his age.

Hatfield remained with the Giants throughout the 1888 season, filling in at second, third, and shortstop for a pennant-winning (84-47-7, .641) ball club. Early in the campaign, it was observed that “Hatfield has shown himself to be a very lively and fairly reliable fielder, but with the stick has batted weak.”28 Those performance characteristics continued season-long, particularly with Hatfield’s batting. For the year, he posted an anemic .181 batting average, with only one of his 19 base hits going for extra bases.

Gil saw no action in the ensuing best-of-10 World Series against the American Association champion St. Louis Browns until the crown had been clinched by the Giants. In the meaningless final two games, Hatfield notched some time in the infield and turned in a dismal relief effort (12 hits and seven runs allowed in five innings pitched) in Game 10. Notwithstanding such lackluster performance, Sporting Life remained in Hatfield’s corner. “Of course he is not the man [future Hall of Famer John Montgomery] Ward is,” allowed the baseball weekly. “But every young player must have a chance. Hatfield is a steady young player, and if he has the chance he will make good.”29 At the time the press seemed oblivious to the fact that “young player” Hatfield was five years older than Ward.

The New York Giants encored the following season, posting a pennant-winning 83-43-5 (.659) record. So did Gil Hatfield, who again filled in capably around the infield but barely hit his weight, turning in a .184 batting average in 32 games. He also went 2-4 in six pitching appearances. New York repeated as world champions, besting the AA Brooklyn Bridegrooms in the 1889 Fall Classic. But Hatfield so no action in the Series. He was in attendance, however, at a celebratory post-Series banquet held at the Broadway Theater wherein Giants manager Jim Mutrie, team captain Buck Ewing, and star shortstop Ward made gracious speeches.30 Two weeks later, continuation of the evening’s good feelings ended with announcement that a new player-controlled rival major league would take the field for the 1890 season.

The Players League was the brainchild of the visionary Ward, and most of his Giants teammates, including Gil Hatfield, signed with the New York club of the fledgling circuit. Happily, for Gil, Ward himself was taking the helm of the PL’s Brooklyn team, thereby opening up some playing time at shortstop. Unhappily for him, PL Giants field leader Ewing preferred to shift second baseman Danny Richardson to short and placed Giants veterans Roger Connor and Art Whitney and new arrival Dan Shannon at the other infield spots. Still, Hatfield got more than his previous playing time. In July, he was loaned to the league-leading but injury-depleted PL Boston Reds and played short “brilliantly” for three games, all Boston victories.31 The irregularity of the transfer, however, prompted a vigorous protest from Brooklyn club leader Ward. League officials then voided the Hatfield rental and nullified the game results.32 As it turned out, the games were never replayed as Boston won the first and only Players League pennant by a margin exceeding three games.33

In the meantime, Hatfield returned to the Giants, where he finished the season with a respectable .272 batting average in 74 games played, combined. The collapse of the Players League and the ensuing merger of the NL New York Giants and PL New York Giants franchises, however, did not bode well for him. At the 1890 season’s end, it was reported that “Gil Hatfield thinks that he will not be with the Giants next season. He says that he has been treated well by enough by manager Ewing, but has not been given a good trial since his advent in New York.”34 Hatfield got his long-awaited chance the following year, becoming the everyday shortstop for the worst team in major league baseball: the American Association’s newly minted Washington Statesmen.35

The Statesmen were a lousy (44-91-4, .326) ball club, and about all that can be said for Hatfield is that he was far from their worst regular. Playing in 134 games, he hit a mediocre .256, but led the team in runs scored (83) and stolen bases (43). He also played tolerable bare-handed infield defense and pitched some mop-up relief. And finally, during this dreary season the press began to take notice of Hatfield’s true age (36). In a nationally syndicated column, sportswriter Willliam Harris observed that the “coltish” descriptive frequently applied to Hatfield was inapt. “A ball player after 15 years service ceases to be coltish,” wrote Harris.36 From that point on, our subject was no longer “young” Gil Hatfield.

That winter, the Washington franchise was among those absorbed when the National League incorporated the American Association. Reports that the available Hatfield might be reacquired by the Giants proved unfounded, and he spent the 1892 season back in the minors playing for clubs in the far west. Gil took over as playing manager of the Seattle Blues of the Pacific Northwest League at midseason and guided the club to the second-half championship.37 After the PNWL folded in late August, he completed the season playing a handful of games for Helena in the independent Montana State League.

Hatfield moved back east for the 1893 season, signing with the Charleston Seagulls of the Southern League.38 Early in the campaign, however, he had to leave the club to attend his father’s funeral.39 In time, the passing of General Hatfield gave rise to the outlandish tale that son Gil had inherited the then-staggering sum of $75,000.40 One breathless press dispatch even described him as “probably the wealthiest ballplayer in the country.”41 In fact, the vast bulk of father Hatfield’s considerable estate went to feckless eldest son John.42 Specific estate assets (paintings, jewelry, etc.) were left to various other Hatfield family members. All that was bequeathed to estate coexecutor Gilbert Hatfield was the negligible estate residuum, and even that was to be shared equally with John Hatfield.43

After his father was laid to rest, Gil returned to Charleston, where he played well. In 76 games, he batted a solid .283, with 22 extra-base hits and 79 runs scored. He also provided competent defense at second and third base for the Seagulls. That performance earned Hatfield a return trip to the majors, being signed in mid-August by Brooklyn club boss Charles Byrne.44 Supplanting George Shoch at third, “Gil Hatfield made his debut [on August 18] … and put up a great game in the field, while his stick work resulted in a home run.”45 He also hit a triple in sparking the Grooms to an 8-4 victory over Cincinnati. Doubtless benefiting from the recent elongation of the pitching distance to the modern-day 60 feet, six inches, Hatfield went on to hit a robust (for him) .292 in 34 games. His defense (.875 fielding percentage), however, was not as good as that provided by Shoch (.911) or Tom Daly (.892), and Hatfield was released by Brooklyn over the winter.

Signed for the 1894 season by the Toledo White Sox of the Western League, Hatfield continued his resurgence at the plate. In 125 games for the second-place (67-55, .549) Sox, his batting average soared to a career-high .355 (which did not even place him inside the WL Top 20) for the turbo-charged 1894 season,46 with 51 extra-base hits, 160 runs scored, and 43 stolen bases. As a result, once again a major league ball club enlisted Hatfield’s services. That winter, he was acquired by the NL Louisville Colonels in the minor league player draft.47 But at age 40, the big-league game had finally grown too fast for him. After batting .188 (3-for-16) in five early season contests, Hatfield was sold to the Kansas City Cowboys of the Western League.48 His major league career had come to its end.

In 320 games spread out over eight seasons, Gil Hatfield recorded a soft .247/.313/.317 slash line, while his defense at seven different positions was never much more than adequate. And as a pitcher (3-5, with a bloated 5.56 ERA in 77 2/3 innings), he had been good for only a few meaningless starts or mop-up work in hopelessly lost contests. Nevertheless, Hatfield had been a useful addition to most of the clubs for which he played. His positional versatility in an era of limited player rosters was a genuine asset, as was his baseball intelligence. On top of that, he was a positive presence in the locker room, a quiet, sober, amiable man well-liked by teammates, club management, and the sporting press, alike. In fact, Hatfield’s pleasing personality and genial disposition may well have had as much to do with his repeated engagement at the game’s highest echelon as did his modest playing abilities.

Predictably, Hatfield soldiered on after his final major league demotion. He spent the 1895 and 1896 seasons in the Kansas City infield. At the close of the latter season, it was observed that next to venerable Chicago Colts manager-first baseman Cap Anson, Gil Hatfield was “the oldest man playing ball.”49 And he continued playing, for the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Bob-o-Links of the Western League and the Atlantic League Newark Colts in 1897, and the New London Whalers of the Connecticut State League the following two seasons. New Haven reserved Hatfield for the 1900 season50 but he declined to return. Instead, he assumed a teller position with the Hudson Trust Company of Jersey City. He remained in the bank’s employ for the remainder of his life.

Although his time in Organized Baseball was behind him, Hatfield remained active in the game. He umpired local semipro games, managed the Hoboken Athletic Club nine, and pitched the occasional old-timers game, his final outing coming at age 51.51 He also took up trapshooting, and quickly became a competitive match mainstay for the Brooklyn Gun Club.52 He was also an expert deep-sea fisherman. When not at work or engaged with his leisure pursuits, Hatfield enjoyed a quiet life at home with wife Grace and younger daughter Ruth.

In his later years, Hatfield developed heart disease. But his sudden death on the afternoon of May 26, 1921, came as a shock. Not feeling well, he paid a visit to the office of his brother-in-law, Dr. Frank Child, a physician in Hoboken. After giving him some medication, Dr. Child drove Gil back toward the bank, but reversed course when his patient complained of weakness and dizziness. Shortly after they arrived back at the doctor’s office, Hatfield suffered a heart attack and died.53 He was 66.

Following funeral services conducted at the Hatfield residence, the deceased was laid to rest at Fairview Cemetery in Fairview, New Jersey. Survivors included his wife, two daughters, and two grandchildren.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information provided above include the Gil Hatfield file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Hatfield profiles published in the New York Clipper, July 27, 1889, and Major League Player Profiles: 1871-1900, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census and other governmental records accessed via Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 During the Civil War, James Hatfield served briefly as colonel of a New Jersey volunteer regiment in the Union Army. The basis for his “General Hatfield” nickname was undiscovered.

2 In 1889, an inane wire service article alleged that our subject was related to the Hatfield clan of West Virginia and that he had been targeted for assassination by the rival McCoys. See e.g., “The Base Ball World,” Minneapolis Times, November 10, 1889: 7. Gil’s family, however, traced its roots to Westchester County, New York, and was unconnected to the notorious Appalachian hillbillies of the same name.

3 The commercial and civic accomplishments of grandfather Gilbert T. Hatfield were noted in obituaries published in the New York Herald and New York Times, April 10, 1880.

4 As reflected in the 1860 US Census. The other Hatfield children were Bertinette (born 1844), John (1847), and Eleanor (1850). After the death of their mother, James Hatfield’s second marriage spawned half-siblings Jennie (1864) and Junior (James, 1873).

5 In October 1872 John Hatfield set a long-distance baseball throwing record (400 feet, seven inches) that stood for almost 40 years.

6 According to “Diamond Favorites of the Old N.E. League,” Portland (Maine) Sunday Telegram, July 5, 1914: 15.

7 Per the Gil Hatfield profile in Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 461-462.

8 “Diamond Favorites,” above.

9 Gil was likely the unidentified Hatfield playing second base for the Nameless Club in an August 1880 amateur title match played in Brooklyn. See “Prospect Park Championship,” New York Clipper, August 14, 1880: 163.

10 Per the Gil Hatfield sketch published in the New York Clipper, July 27, 1889. See also, “Who’s Who in Baseball: Past and Present,” Washington (DC) Herald, September 11, 1910: 28.

11 As reported in “A New Ball Nine in the Local Area,” Hartford Courant, August 24, 1883: 2, which lists Hatfield as the team’s second baseman. See also the Gilbert Hatfield profile published in the New York Clipper, July 27, 1889.

12 Per game accounts/box scores published in the Hartford Courant, August-September 1883.

13 See “Notice to Association Clubs,” Sporting Life, September 17, 1883: 4.

14 Hatfield’s contract with Baltimore was approved by Eastern League secretary Henry H. Diddlebock in January 1884. See “Official Notice,” Sporting Life, January 16, 1884: 2.

15 The addition of Hatfield to the Newark club was noted in “Lost in Ten Innings,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, July 10, 1884: 1.

16 Per “Base Ball Men in Hard Luck,” Hartford Courant, September 17, 1884: 2.

17 See “Base Ball Notes,” Hartford Courant, September 19, 1884: 2.

18 “Notes and Commentary,” Sporting Life, December 3, 1884: 5.

19 “In the Diamond Field,” New York Times, September 25, 1885: 3. See also, “Sporting Notes,” (Hoboken, New Jersey) Hudson County Democrat-Advertiser, September 26, 1885: 2.

20 Per “Sporting Notes,” Hudson County Democrat-Advertiser, February 13, 1886: 2.

21 Baseball-Reference has no stats for Hatfield’s 1886 season with Portland. But from the 79 box scores published in the local press, Gil batted somewhere in the neighborhood of .284, with 14 extra-base hits. He posted a respectable .868 FA in 74 games at third base and went 3-1 in eight pitching appearances.

22 See “Hatfield-Child,” Hudson County Democrat-Advertiser, April 2, 1887: 2; “Hoboken Happenings,” Jersey City News, March 18, 1887: 4.

23 With 57 walks counted as base hits under an anomalous 1887-only scoring rule, Hatfield’s official batting average was .414.

24 “Sporting Notes,” Worcester Daily Spy, September 12, 1887: 1.

25 “Hatfield to Go to New York,” Portland Daily Press, September 12, 1887: 1. New York reportedly paid $1,750 for Hatfield’s release.

26 “New-York Beaten Again,” New York Times, October 9, 1887: 3.

27 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, October 19, 1887: 3.

28 “Gotham’s Chief Club,” Sporting Life, May 16, 1888: 2.

29 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, November 21, 1888:6.

30 As reported in “Honoring Champions,” Sporting Life, October 30, 1889: 2.

31 The description of Hatfield’s fielding in “Base ball Notes,” Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1890: 6.

32 As reported in “Hatfield’s Cost,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1890: 5; “Boston Games Thrown Out,” New York Evening World, July 17, 1890: 1.

33 The three games were subsequently declared no-decisions, with individual player stats retained for PL record-keeping purposes.

34 “Base Ball Briefs,” Pittsburg Press, October 12, 1890: 6; “Sporting Notes,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 9, 1890: 6.

35 Hatfield’s signing with the new Washington club was noted in “The Base Ball Assn.,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, February 12, 1891: 4; “Base Ball Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, February 5, 1891: 5; and elsewhere.

36 W.I. Harris, “Ten Photographs,” published in the Cheyenne (Wyoming) Daily Leader, June 14, 1891: 4; Lima (Ohio) Daily Times, June 5, 1891: 3; Fall River (Massachusetts) Daily Globe, June 3, 1891: 3; and elsewhere.

37 Taking over a Seattle team that had posted a 19-27 record for first-half manager Abner Powell, Hatfield brought the Blues home with a 19-10 finish.

38 As reported in “Base Ball Chatter,” Pittsburgh Post, February 5, 1893: 6; “Base Ball Notes,” Portland (Maine) Evening Express, February 2, 1893: 5; and elsewhere.

39 Per “Gossip of Baseball,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 5, 1893: 8.

40 See e.g., “Gil Hatfield’s Good Fortune,” (South Omaha) Daily Stockman, February 14, 1895: 3; “Rich Ball Player,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, February 13, 1895: 7; “Lucky Gil Hatfield,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, February 13, 1895: 7.

41 “Sporting,” St. Louis Republic, February 11, 1895: 2.

42 John Hatfield had left his wife and young children destitute in Manhattan to pursue life as a racetrack bookmaker in St. Louis.

43 As reflected in the Last Will and Testament of James T. Hatfield, admitted to probate July 1, 1893, and accessed on-line by the writer via Ancestry.com.

44 Per “Hatfield Will Wear a Brooklyn Uniform,” (Brooklyn) Standard Union, August 17, 1893: 3.

45 “Baseball,” Standard Union, August 19, 1893: 8.

46 Hunky Hines of Minneapolis captured the Western League batting crown with a .427 BA.

47 As reported in “Gil Hatfield Offers to Sign,” Sporting Life, February 16, 1895: 7; “Base Ball Notes and Gossip,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, February 15, 1895: 8.

48 As reported in “Personal,” Sporting Life, May 18, 1895: 9; “Manning Secures Hatfield,” Kansas City Journal, May 12, 1895: 2; and elsewhere.

49 “Base-Ball Notes,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, December 23, 1896: 4.

50 Per “The Reserves,” Sporting Life, October 7, 1899: 9.

51 See “Big Crowd of Fans Expected to See Contest,” (Jersey City, New Jersey) Observer, June 22, 1906: 9. With game proceeds going to a local hospital, Hatfield pitched for a side composed of Jersey Blues alumni against a team from the Hoboken Police Department. The accompanying team photo is the last one known to depict Gil Hatfield.

52 See e.g., the match scores published in the Standard Union, November 28, 1902: 2.

53 Per “‘Gil’ Hatfield Dies Suddenly in Doctor’s Office,” (Hoboken, New Jersey) Hudson Observer, May 27, 1921: 2, which reported that the deceased was “loved and respected by both employers and fellow employees alike.”

Full Name

Gilbert Hatfield

Born

January 27, 1855 at Hoboken, NJ (USA)

Died

May 26, 1921 at Hoboken, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.