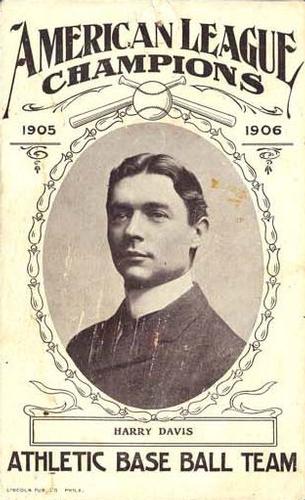

Harry Davis

Long before Babe Ruth revolutionized the game with the home run, during a period when hitting a baseball was likened by some to swatting a cabbage, Harry Davis was one of the country’s most feared sluggers. Known today primarily for leading the American League in home runs four consecutive seasons, the right-handed Davis was as apt to win games with his brains as he was with his bat. Hand picked by Connie Mack, he was the heart and soul of the early Philadelphia Athletics teams who dominated the newly formed A.L., winning six titles and three World Series. Davis really had two separate major league careers: one before 1900 and the other after; one as an itinerant player without a steady team or position, the other as the cornerstone of a dynasty. He was credited with being “at least 25 per cent of the brains of the Philadelphia American League baseball club.” Over a career that spanned more than thirty years as a player, coach, manager and scout, Harry Davis was one of the most respected and admired figures in baseball.

Long before Babe Ruth revolutionized the game with the home run, during a period when hitting a baseball was likened by some to swatting a cabbage, Harry Davis was one of the country’s most feared sluggers. Known today primarily for leading the American League in home runs four consecutive seasons, the right-handed Davis was as apt to win games with his brains as he was with his bat. Hand picked by Connie Mack, he was the heart and soul of the early Philadelphia Athletics teams who dominated the newly formed A.L., winning six titles and three World Series. Davis really had two separate major league careers: one before 1900 and the other after; one as an itinerant player without a steady team or position, the other as the cornerstone of a dynasty. He was credited with being “at least 25 per cent of the brains of the Philadelphia American League baseball club.” Over a career that spanned more than thirty years as a player, coach, manager and scout, Harry Davis was one of the most respected and admired figures in baseball.

Harry Davis was born in Philadelphia on July 19, 1873, the oldest of four children. His father, John, was a shoemaker, and his mother, Mary, took in wash. Christened simply Harry Davis, he added the middle initial H later in life to differentiate himself from the numerous other Harry Davises in and around Philadelphia. Considering there was a notorious gangster in Ohio named Harry Davis, another in politics, and a prominent Pennsylvania theater owner with the same name, it is no wonder he wished to more clearly identify himself.

His father died of typhoid when he was five and his mother, unable to provide for the family, applied in September 1879, to send Harry to Girard College, the famous Philadelphia elementary and high school for disadvantaged and orphaned boys. He was finally accepted, and enrolled on January 3, 1882. There he excelled in business and accounting and became interested in baseball. Girard College, at the time, was a fertile source of baseball talent, eventually sending several players to the major leagues, including Moose McCormick and Johnny Lush. While there, Davis primarily caught and played the outfield. During his years at Girard College, Harry also was given the nickname Jasper by his schoolmates, a name by which he would be familiarly known for the rest of his life.

Harry graduated from Girard College in June, 1891, and that summer caught for the Bank Clerks’ Athletic Club in the Amateur League of Philadelphia. He later played in the Philadelphia area with the Pennsylvania Railroad club before signing his first professional contract with Providence of the Eastern League in 1894. He batted .412 in a five-game trial before being dispatched to Pawtucket in the less-advanced New England League, where he batted .369 to rank second in the circuit. The following year, playing and managing part-time for Pawtucket, he led the New England League in batting (.404), hits (200), doubles (49), and home runs (17). He was subsequently purchased by the New York Giants.

Harry joined the Giants after the minor league season ended and made his major league debut with them on September 21, 1895, getting three hits against Boston, including a bases loaded triple. Davis drove in five runs in his team’s 13-12 loss. In the wake of a disappointing season for the Gothamites, the papers were full of glowing reports about Davis. O.P. Caylor of the New York Herald, never known for his reserve, bubbled, “He is the find of the season. Davis is highly intelligent, quick-witted, cool as a veteran and a natural ball player. If he does not turn out to be a second Mike [King] Kelly, indications are worthless. [He] will be the idol of the Polo Grounds patrons.”

Spending most of his time in left field, Davis got off to a good start at the plate in 1896 and was on a pace to drive in over 100 runs. Despite being regarded as a good fielder, though, with a strong, accurate arm, Harry’s fielding was sub-par. Only 22, he also suffered from rheumatism and for these reasons, apparently, the Giants were willing to give him up despite the initial ballyhoo. During a doubleheader on July 25, he was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates, along with $1,000, for Jake Beckley. Connie Mack, Pittsburgh manager at the time, immediately proclaimed Davis to be the everyday first baseman. The trade was not well received in Pittsburgh as the popular Beckley, though having an uncharacteristically poor year, proved productive for several years thereafter, while Davis was a dud with the Pirates, batting .190 over 44 games.

Davis improved to bat .305 in 111 games for the Pirates in 1897, and also emerged as one of the team’s main power sources, connecting for a league-leading 28 triples–which remains the fifth-highest total in major league history–while hitting only 10 doubles, a statistical peculiarity no one has ever matched. On March 1, 1898, before heading to spring training with the Pirates, Harry was married to Miss Eleanor Hicks of Philadelphia. Together they would have two sons, Harry C. and Eugene. The next two seasons were marked by injuries and frustration. When healthy, Harry produced, but leg and ankle injuries often forced him out of the lineup. The Pirates sold him to Louisville in July, 1898, and after hitting only .217 for the Colonels, he was released on September 10. Picked up by Washington in October, he appeared in one game for the club before the season ended. 1899 was no better. Harry appeared in only 18 games for the Senators, hitting .188, and was released to Providence of the Eastern League in May.

The rest of 1899 and all of 1900 were spent back in Providence. Harry performed very well, hitting over .300 and leading the league in doubles both seasons, and led the league in steals in 1899 with 70. When 1901 rolled around, bidding wars with the American League decimated the Providence roster, and Harry, who was not signed by the new major league, decided he had had enough of professional baseball. He returned to Philadelphia and took a job with the Pennsylvania Railroad. It wasn’t long before Connie Mack, now managing the Philadelphia American League franchise, contacted him about playing first base for the Athletics. After some convincing, Harry agreed and joined the team on May 22 in Chicago. Off to a terrible start, the A’s turned it around to finish with a winning record. Harry hit over .300 and remained the A’s starting first baseman for the next ten seasons. On July 10, against Boston, he hit for the cycle for the only time in his career.

In 1902 Harry batted over .300 again and led the AL in doubles as the Athletics won their first pennant. In August, several years before Germany Schaefer made it popular, he stole first base against the Tigers on August 13, 1902. Late in the game, Dave Fultz was on third and Harry on first. Harry took off for second, in an attempted double steal, and got into a rundown. Fultz edged off third until he finally drew a throw, but dove back in safely, and Harry wound up on second. Before anyone realized what was happening, Davis ran back to first, making it easily without a throw. Then, before Tigers pitcher George Mullin could deliver a pitch, Harry was off again for second. Mullin threw to second and Fultz dashed for home, beating the throw in. Harry was safe at second again, and each man was credited with a stolen base.

In 1903, Davis’s production increased slightly, but injuries kept him out of over 30 games. He began to find his home run stroke, though, equaling his previous season’s total of six in over a hundred fewer at bats. The following year, he led the American League for the first time with ten, beginning a run of four consecutive home run titles. The A’s finished fifth in 1904, but the following year they edged out the White Sox for their second A.L. crown. Besides leading in homers, Harry paced the league in runs, doubles, and RBI, and finished tied for fifth with a career high 36 stolen bases. In his first World Series, against John McGraw‘s New York Giants, he and the rest of the A’s were stymied by Christy Mathewson, losing in five games.

Harry earned a reputation over the years as a thinking man’s ballplayer, a teacher and a gentleman. Playing for Connie Mack, who discouraged his players from kicking and fighting, had a lot to do with creating this image, but Harry was full of fire, too, and not afraid to say what was on his mind. Back in his early days with the Giants, O.P. Caylor wrote that Harry “blossomed into a kicker of class A. He can give McGraw two jumps, a hundred words, and beat him in a canter. Harry has a voice that puts [Patsy] Tebeau‘s to shame, and when he isn’t denouncing the rascality of the umpire to the latter’s face, he is talking to himself about human depravity in general.” Harry was a team leader and following the sale of Lave Cross after the 1905 season, Mack named him captain of the Athletics. He had become Philadelphia’s leader on the field and was widely recognized as Mack’s lieutenant. Off the field, he took promising players under his wing, boarding them in his own house. From future Hall of Famers like Eddie Plank and Eddie Collins to rookies like Billy Orr, many players could cite Davis as a big influence on their careers.

Davis had his best season in 1906, but the next few campaigns saw Harry’s offensive numbers decline as the A’s finished up and down in the standings. Although he led the league in home runs again in 1906 and 1907, his power began to dwindle in the latter year. After posting slugging percentages better than .400 every season from 1901 to 1906, Davis never again cleared the .400 barrier, and his extra base hit totals dwindled as his speed vanished.

Philadelphia was back on top in 1910, but at the age of thirty-six, Harry was reaching the end of the line. With most of his power gone, he hit only one home run. Another Girard College alum, Ben Houser, was being groomed to take his place at first base. Under Harry’s tutelage, Houser fielded well, but struggled at the plate, and Harry wound up playing most of the season. The A’s won their first pennant since 1905 and, with Davis batting a robust .353 in the World Series, won their first world championship, beating the Cubs in five games.

1911 would be Harry’s last real hurrah with the Athletics as a player, although it did not get off to a promising start. Harry struggled mightily at the plate in the early season, starting out 2-for-28 as the A’s stumbled out of the gate in April. It was early May before the team reached .500. On May 3, at the Hilltop Grounds in New York, Harry hit his last home run, a long drive into the centerfield bleachers, as the A’s beat the Highlanders. Fittingly, Jack “Stuffy” McInnis, the A’s young recruit who would soon take Davis’s place, also homered in that game. The torch was passed, though no one knew it at the time. McInnis, known historically for the high quality of his fielding at first base, ironically played himself into a regular position because of his bat. His work at shortstop for the A’s was abysmal, but he was hitting well over .400 and Harry wasn’t hitting a lick. By early June, McInnis was the regular first baseman and Davis’s playing days were virtually over. Harry, ever the professional, handled the move with class, tutoring McInnis on the finer points of play around first, and the youngster eventually developed into one of the finest fielders in history. The A’s began winning and took the pennant going away.

In late September, McInnis was hit on the wrist by a George Mullin pitch and could not play regularly in the World Series. Mack was forced to rely on his aging lieutenant to play first and there was talk before the series that this would be a major disadvantage for the A’s. Although he hit only .208, Harry acquitted himself nicely, driving in five runs with timely hits to tie teammate Home Run Baker for the series lead, as the A’s won their second consecutive championship, beating McGraw’s Giants. With two outs in the bottom of the ninth in the Series’ final game, Davis initiated a symbolic changing of the guard, leaving the field before the final out so McInnis could be at first base when the championship was won. Davis got a standing ovation from his home fans for the classy gesture, and McInnis made the final putout to clinch the title.

Well before the end of the 1911 season, Harry had signed a contract to manage Cleveland in 1912. Despite his extensive experience in the game and the respect he commanded from his fellow players, Davis’s managerial tenure was not a successful one. His first managerial moves did not go over well with the home town fans. He traded the popular but light-hitting George Stovall, whom Davis had replaced as manager, to the St. Louis Browns for Lefty George, a 4-9 pitcher who never won another game in the A.L. Some viewed this as a sign of insecurity, but Harry wanted left-handed pitching. It wound up leaving the Naps with a gaping hole at first base for the entire season. Then, in a move that had many scratching their heads, he appointed Ivy Olson team captain, thereby alienating the many fans of Harry’s former teammate, Nap Lajoie. The club was beset by injuries and when it didn’t perform well, Davis was critical to the press and accused his players of quitting on him. The press and the pubic, in turn, roasted him for the moves he made and maintained Stovall would have done better had he remained. Gus Fisher, a catcher whom Harry let go during spring training, claimed Davis’s “ivory-skulled work…[was] directly responsible for the poor showing.” Finally, in early September, with the Naps mired in sixth place, Harry resigned and Joe Birmingham took over.

Harry signed back on as a coach with his old team for 1913, amid speculation that he would eventually take Mack’s place. This, of course, never happened, but with Davis back on the payroll, the A’s proceeded to win another world championship, beating the Giants once more, four games to one. Harry, who batted .353 in seven games during the season, did not play in the World Series. The A’s celebration, however, was delayed and subdued by news of the death of Harry’s eldest son, Harry Jr., the day after the team returned to Philadelphia. The 13-year-old died suddenly of a liver condition reportedly exacerbated by the excitement of the Athletics’ victory. The $100,000 infield of McInnis, Baker, Eddie Collins and Jack Barry, and pitchers Eddie Plank and Chief Bender were pallbearers at the boy’s funeral and joined in mourning Harry’s loss.

From 1914 to 1917, Harry continued to serve as a coach for Connie Mack, occasionally appearing in games, mostly as a pinch hitter. Following the 1917 season, Harry retired temporarily upon his November election to the Philadelphia city council, but was back by mid-1919 and remained with the A’s as a coach and a scout until 1927.

During his career, and after, Harry had many business endeavors. He owned a scrap iron business, was a clerk in the municipality of Philadelphia, and owned a bowling alley later in his career. He also enjoyed bowling, golfing, and trapshooting. In his later years, up until his death, he was working as a foreman for the Burns Detective Agency, guarding the rotogravure plant at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Harry Davis died of a stroke at his home in Philadelphia on August 11, 1947. Upon learning of his death, Connie Mack lamented, “All baseball will miss him. He was a great hitter and fielder, but above all, he was a team player.” He is buried at Westminster Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Montgomery County, PA.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Thorn, John, et al. Total Baseball, Eighth Edition. Total Sports, 2003.

Johnson, Lloyd, et al. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. Baseball America.

Smith, Ira L., Baseball’s Famous First Basemen. Barnes, 1956.

McConnell, Bob and David Vincent. SABR Presents the Home Run Encyclopedia. Macmillan, 1996.

Baseball-Reference.com

Chicago Tribune, 1894-1919.

New York Times, 1894-1920, 1947.

Washington Post, 1894-1920.

The Sporting News, 1894-1920, 1947.

Philadelphia Inquirer, 1913.

Baseball Magazine, 1911.

Harry Davis player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame

Girard College Alumni Association

Full Name

Harry H. Davis

Born

July 18, 1873 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

August 11, 1947 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.