Jake Beckley

When Jake Beckley gained election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971, 53 years after his death, most baseball fans had no idea who he was or why he should be honored with a plaque in Cooperstown. Beckley’s reputation suffered because he never played on a pennant winner, and only one team he played for (the 1893 Pirates) finished as high as second place. Still, the colorful “Eagle Eye” compiled a .308 lifetime average, hit .300 or better in 13 of his 20 seasons (including the first four seasons of the Deadball Era), and retired in 1907 as baseball’s all-time leader in triples. Beckley still stands fourth on the all-time list of three-baggers, behind only Sam Crawford, Ty Cobb, and Honus Wagner. He held the career record for games played at first base until 1994, when Eddie Murray passed him, but he still leads all first basemen in putouts and total chances.

When Jake Beckley gained election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971, 53 years after his death, most baseball fans had no idea who he was or why he should be honored with a plaque in Cooperstown. Beckley’s reputation suffered because he never played on a pennant winner, and only one team he played for (the 1893 Pirates) finished as high as second place. Still, the colorful “Eagle Eye” compiled a .308 lifetime average, hit .300 or better in 13 of his 20 seasons (including the first four seasons of the Deadball Era), and retired in 1907 as baseball’s all-time leader in triples. Beckley still stands fourth on the all-time list of three-baggers, behind only Sam Crawford, Ty Cobb, and Honus Wagner. He held the career record for games played at first base until 1994, when Eddie Murray passed him, but he still leads all first basemen in putouts and total chances.

Jacob Peter Beckley was born on August 4, 1867, in Hannibal, Missouri, the Mississippi River town that Mark Twain made famous. A left-handed batter and thrower, Jake played in his teenage years for fast semipro teams in the Hannibal area. Bob Hart, a former teammate from Hannibal, arranged his introduction to professional ball. While pitching in the Western League for Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1886, Hart recommended the 18-year-old Jake Beckley to his manager. Beckley traveled to Leavenworth and batted .342 in 75 games, playing mostly second base and the outfield. Though left-handed throwers still played second, short, and third in the 1880s, Jake really didn’t have the arm strength to play any position except first base. Leavenworth moved him there the following season, and that is where he remained for the rest of his lengthy career.

Beckley batted over .400 in 1887 (walks counted as hits that season), splitting the summer between Leavenworth and another Western League team in Lincoln, Nebraska. The following year Lincoln sold the steadily improving first baseman to the Western Association’s St. Louis Whites. Beckley played only 34 games before the Whites sold him in June 1888 to the National League’s Pittsburgh Alleghenies for $4,000. Still only 20 years old, Jake batted .343 as a rookie and solidified the right side of the Pittsburgh infield with his defensive play. The next year he again led the club’s regulars in batting and soon earned the nickname “Eagle Eye”—not for his ability to draw bases on balls (his walk totals were consistently below the league average) but for his batting skill. The hard-hitting Beckley brought a dash of excitement to the Alleghenies, and before long he became the most popular player on the Pittsburgh team.

In the spring of 1890 Beckley interrupted his NL career when he, along with eight of his teammates and manager Ned Hanlon, jumped to the Pittsburgh entry of the new Players League. Jake considered staying with the Alleghenies but the new league offered him a higher salary, and, as he explained, “I’m only in this game for the money anyway.” He belted 22 triples to lead the Players League, while the Alleghenies missed him and their other stars so much that they fell all the way to last place. The Players League collapsed after one season and Beckley returned to the Alleghenies (soon to be called the Pirates) for the 1891 campaign.

Jake married in 1891 but his wife Molly died after only seven months. He slumped badly after her death, with his batting average plummeting to a career-low .236 in 1892. Jake didn’t marry again until his baseball career was over. “Eagle Eye” returned to the .300 mark from 1893 to 1895, but when he slumped again in 1896 the Pirates, over the loud objections of their fans, traded him to the New York Giants for Harry Davis and $1,000 in cash. Beckley didn’t hit well in New York, either, and most people thought his career was over when the Giants released him in May 1897. Fortunately for Jake, the Cincinnati Reds needed a first baseman and signed him a few weeks later. His bat came alive again in Cincinnati, and on September 26, 1897, Beckley belted three homers in a game against St. Louis. No other major leaguer performed that feat again until Ken Williams did it in 1922.

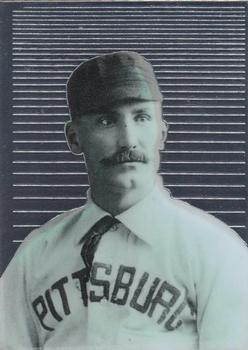

Beckley was a handsome man, though one of his eyes was slightly crossed, and kept his impressive mustache long after all but a handful of players had relinquished theirs; at the time of his retirement he was one of only three men in the majors who still sported facial hair. He also displayed several other idiosyncrasies. Beckley yelled “Chickazoola!” to rattle opposing pitchers when he was on a batting tear, and he perfected the unusual (and now-illegal) practice of bunting with the handle of his bat. As the pitch approached the plate, Jake flipped the bat around in his hands and tapped the ball with the handle. Casey Stengel was a teenager when he saw the maneuver performed. “I showed our players,” said Stengel 50 years later, when he was managing the Yankees, “and they say it’s the silliest thing they ever saw, which it probably is but [Beckley] done it.”

Jake Beckley wasn’t afraid to bend the rules. Despite his stocky build (he stood 5’10” and weighed 200 lbs.), he ran well enough to reach double figures in stolen bases and triples almost every year, but he also didn’t mind cutting across the infield if the umpire’s back was turned. One day, when umpire Tim Hurst wasn’t looking, Jake ran almost directly from second base to home, sliding in without a throw. Hurst called Beckley out anyway. “You big son of a bitch,” shouted Hurst, “you got here too fast!”

Jake also loved pulling the hidden-ball trick and tried it on every new player who came into the league. Sometimes he hid the ball in his clothing or under his arm, and other times he hid it under the base sack and waited for the unsuspecting player to wander off first. One day, with Louisville’s Honus Wagner on first, Jake smuggled an extra ball onto the field and put it under his armpit, partially exposed so Wagner could see it. When the umpire’s back was turned, Wagner grabbed the ball and heaved it into the outfield. Wagner lit out for second, but the pitcher still held the game ball and threw Wagner out.

For seven years Beckley played first base for the Reds, batting over .300 in every season except 1898. His career nearly ended on May 8, 1901, when Christy Mathewson hit him in the head with a fastball, knocking him unconscious for more than five minutes. Beckley recovered, missing only two games, and hit .307 for the last-place Reds that season. He was “Old Eagle Eye” by then, but still a solid run producer with good range and quick reflexes on defense. His only weakness remained his poor throwing arm, and National League base runners always knew they could take an extra base on him. Beckley once fielded a bunt and threw wildly past first base. He retrieved the ball himself and saw the runner rounding third and heading for home. Rather than risk another bad throw, Jake raced the runner to home plate and tagged him in time for the out.

The veteran first baseman pitched for the only time in his career on the last day of the 1902 campaign. The Reds were in Pittsburgh on a rainy, muddy day, and Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss insisted on playing even though the Pirates had clinched the pennant weeks before. To show his dismay, Reds manager Joe Kelley tapped the scatter-armed Beckley as his starting pitcher and played other Reds out of position. Jake allowed nine hits and eight runs in his four innings of work, and the game degenerated into a farce. Catcher Rube Vickers, normally a pitcher, committed six passed balls and didn’t even bother chasing Beckley’s wild pitches. The Pirates won, 11-2, but the irate fans forced Dreyfuss to refund all the gate receipts.

Beckley batted .327 in 1903 but manager Kelley wanted to play first base himself, so in February 1904 the Reds sold the 36-year-old star to St. Louis. Jake hit well in his first two seasons with the Cardinals but his batting declined quickly as injuries began to slow him down. He served briefly as a National League umpire in 1906, while on injury leave from the Cardinals, and tried to play again the following spring. In June 1907 the Cardinals released Beckley, ending his 20-year career in the majors.

Jake wasn’t yet finished with baseball. He signed with Kansas City of the Single-A American Association shortly after the Cardinals let him go, and he played there for three years and managed the team for one. After short stints in 1910 with Bartlesville and Topeka, Beckley returned in 1911 to his hometown of Hannibal, where he managed and batted .282 at age 44. In late 1911 he moved to Kansas City and retired from professional ball, though he played on semipro and amateur nines for several more summers. He also helped coach the team at nearby William Jewell College and umpired for the independent Federal League in 1913, the year before the circuit became a short-lived major league.

Jake Beckley operated a grain business in Kansas City after he stopped playing ball. He once placed an order with a Cincinnati company, which cabled back, “We can’t find you in Dun and Bradstreet.” Beckley replied, “Look in Spalding Baseball Guide for any of the last 20 years.” Beckley suffered from a weak heart, and he was only 50 when he died in Kansas City on June 25, 1918. He was buried in Hannibal, where the townspeople erected a small monument to his memory after his election to the Hall of Fame.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

Appel, Marty and Burt Goldblatt. Baseball’s Best: The Hall of Fame Gallery. McGraw-Hill, 1980.

Baseball Magazine. July, 1910.

Lieb, Fred. The Pittsburgh Pirates. Putnam, 1948.

Ritter, Lawrence. The Glory of Their Times. William Morrow and Company, 1984.

Sporting Life. May 19, 1906.

The Sporting News, July 4, 1918.

Full Name

Jacob Peter Beckley

Born

August 4, 1867 at Hannibal, MO (USA)

Died

June 25, 1918 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.