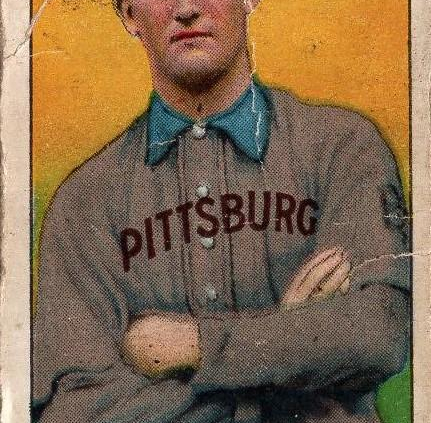

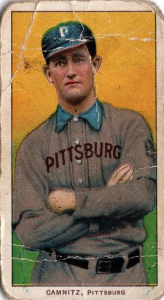

Howie Camnitz

Though his reign as one of the National League’s top pitchers was short-lived, Howie Camnitz was the undisputed ace of the Pittsburgh Pirates pitching staff during their World Championship season of 1909. That season Camnitz, a right-handed curveball specialist, tied for the NL lead in winning percentage (25-6, .806) and ranked fourth in ERA (1.62). “I always inspect very closely the box score of the club we are about to meet next,” he explained to a reporter who asked him for the secret of his success. “My object is to ascertain what players are doing the hitting. Every student of baseball knows that players hit in streaks. If a pitcher has men on bases, and a batsman facing him who has been having a slump in his hitting, he can take a chance on letting him line it out. On the contrary, if a player comes up who has been clouting the ball, it may be the safest plan to let him walk.”

Though his reign as one of the National League’s top pitchers was short-lived, Howie Camnitz was the undisputed ace of the Pittsburgh Pirates pitching staff during their World Championship season of 1909. That season Camnitz, a right-handed curveball specialist, tied for the NL lead in winning percentage (25-6, .806) and ranked fourth in ERA (1.62). “I always inspect very closely the box score of the club we are about to meet next,” he explained to a reporter who asked him for the secret of his success. “My object is to ascertain what players are doing the hitting. Every student of baseball knows that players hit in streaks. If a pitcher has men on bases, and a batsman facing him who has been having a slump in his hitting, he can take a chance on letting him line it out. On the contrary, if a player comes up who has been clouting the ball, it may be the safest plan to let him walk.”

Nicknamed “Rosebud” for his shock of red hair, Samuel Howard Camnitz was born in Covington, Kentucky, on August 22, 1881, the second eldest child of printer Henry Camnitz and his wife Elizabeth. Howie’s brother Harry, who was three years younger, also went on to appear in the major leagues, pitching four innings for the 1909 Pirates and two innings for the 1911 St. Louis Cardinals. Growing up near Bluegrass Country, Howie of course learned to ride horses, a talent he later got to demonstrate at manager Fred Clarke‘s Little Pirate Ranch, but his forte was pitching a baseball. After making his professional debut with Greenville of the Cotton States League in 1902, he enjoyed a breakout season with Vicksburg in 1903, leading the CSL in winning percentage (26-7, .788) and strikeouts (294).

Camnitz started the 1904 season with Pittsburgh, but even with the powerful Pirates behind him he posted a 1-4 record and a 4.22 ERA in 10 games, eight of them in relief, before he was farmed out to Springfield, Illinois. The word on the Kentucky curveballer was that he didn’t “protect” his best pitch: “He would curve the ball over home with such regularity that batsmen cut loose, feeling sure that the oval was there,” wrote one scout. Camnitz returned to the minors and tore up the Three-I League, compiling a 14-5 record and 151 strikeouts in just 19 games. He spent the next two seasons with Toledo of the American Association, topping the 300-inning mark each year and winning 22 games in 1906. Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss stopped by more than once to check on the progress of Camnitz and teammate Otto Knabe, on whom the Pirates had also attached strings. Ultimately Dreyfuss recalled Cammy, exposing Knabe to the minor-league draft, and after the season the Philadelphia Phillies selected the young infielder and made him their regular second baseman for the next seven seasons.

Camnitz quickly demonstrated, however, that Dreyfuss had made the right choice. Beginning his second stint with the Pirates on September 28, 1906, the 25-year-old right-hander fired a seven-inning shutout against the Brooklyn Superbas. Camnitz had learned to “protect” his curveball in the minors, and updated reports noted that he “disguises the pitch excellently now.” In 1907 his career took off, providing the Pirates with a huge return for his $1,200 salary. Appearing in 31 games, including 19 starts, Camnitz went 13-8 with four shutouts and a 2.15 ERA. The following year he was even better, finishing with a 16-9 record, limiting National League hitters to a .210 batting average, and lowering his ERA to a microscopic 1.56, the fourth lowest in the NL. Howie also ranked fourth in the NL in strikeouts per game (4.49).

Yet Camnitz saved his best work for 1909, when he led the Pirates to their first National League pennant since 1903. He began his career year on Opening Day by pitching a shutout against the Cincinnati Reds, the first of his career-high six shutouts that season. In July Camnitz hurled his second one-hitter of the season against the New York Giants; the opposing pitcher, Rube Marquard, broke up the no-hit bid with a sixth-inning bunt single. Pitching a career-high 283 innings, Howie held NL hitters to a .211 batting average and a career-best .267 on-base percentage. In early October, however, his dream season was interrupted by illness—some reports had him suffering with a throat irritation, while others said that he’d fallen off the wagon. Whatever the reason, Camnitz performed dismally in the World Series. Starting Game Two, he was battered for five runs in 2⅓ innings, the last run coming when Ty Cobb swiped home against his replacement, Vic Willis. Camnitz’s only other appearance came in Game Six, when he allowed one run in an inning of relief.

Though he pitched serviceably over the next three seasons, Camnitz’s poor performance in the 1909 World Series marked the beginning of his decline towards mediocrity. His demise came as no surprise to Heinie Zimmerman. “Cammy is always trying and never lets down when there is an alleged weak hitter up,” said the Cubs infielder in 1909. “Howard is such a hard worker that I doubt if he will last as long as the man who occasionally eases up.” Camnitz slipped badly during 1910, ending the season at 12-13 with a 3.22 ERA, almost double his ERA from the previous season. One Pittsburgh sportswriter even called him “fat” (his usual playing weight was 169 lbs.). Dreyfuss stuck with the embattled pitcher, even granting him a hefty $1,200 raise, and over the next two seasons Camnitz posted back-to-back 20-win seasons, though his ERA and ratio of baserunners per nine innings never came close to the level he had established in 1907-09.

By 1913 Howie was walking too many batters—he issued a career-high 107 free passes that year—and, ominously, his strikeout totals dropped precipitously. On August 20, following a 6-17 start, Camnitz and third-baseman Bobby Byrne were dealt to the Phillies for outfielder Cozy Dolan and cash. After a season in which he combined to lose 20 games for two teams that finished in the first division, Howie violated the terms of the reserve clause in his contract and signed with the Pittsburgh franchise in the newly formed Federal League. During training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in March 1914, Dreyfuss had to obtain a court injunction to prevent Camnitz from attempting to recruit Pirates players in the Hotel Eastman and even outside the gates to Whittington Park. Honus Wagner called Howie a “troublemaker” and told him to stay away from the younger players.

Once the season started, it quickly became apparent that Camnitz’s career was on the wane. Pitching in a much less competitive league, Howie could only muster a 14-19 record, compiling a mediocre 3.23 ERA and walking more men than he struck out. Club management blamed the pitcher’s poor 1914 performance on bad conditioning, and just a few weeks into the 1915 campaign Camnitz was accused of violating team rules and handed his unconditional release. According to club officials, in addition to keeping himself in poor shape, Camnitz got into an altercation with another guest at the team’s New York City hotel. “We did everything in our power to protect Camnitz, and he would have continued to be a member of our club had he conducted himself properly,” the club stated in a press release.

Camnitz refused to go away quietly, serving notice to club officials that he would continue to report to the team’s home field, Exposition Park, every day for the remainder of his original contract. In addition, he promised that he would report to the club offices twice each month to collect the paycheck that he believed was still due him. If his pay wasn’t forthcoming, Camnitz threatened a lawsuit. In a letter to club president Edward Gwinner, Camnitz wrote, “As I have been doing regularly every day, I am again reporting for duty, and tendering the club my services.” Gwinner wasn’t impressed. “I see in his notice to us that he says ‘tender the club my services,’” he remarked. “Why, Camnitz has not been in condition to pitch a good game of ball this season, so I don’t think he could give us his services.”

With that final slap in the face, Howie Camnitz’s career in professional baseball finally came to an end. After the 1915 season he retired to private life in Louisville. Camnitz died at age 78 on March 2, 1960, about a month after leaving the auto sales business in which he had worked for over 40 years.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Samuel Howard Camnitz

Born

August 22, 1881 at Covington, KY (USA)

Died

March 2, 1960 at Louisville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.