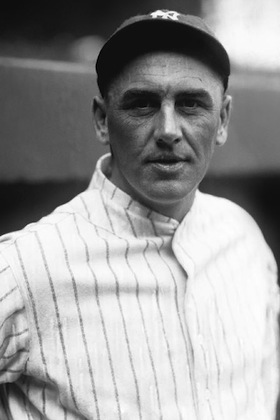

Howie Shanks

“My boy, prepare for the finish. You ain’t got more than a couple of weeks to live.” That is what a doctor told Howard Shanks in 1910. Shanks was told he had consumption (tuberculosis). He had just finished his second year of professional baseball, playing at East Liverpool, Ohio. Barney Dreyfuss of the Pittsburgh Pirates was interested in him, but Shanks only weighed 130 pounds at the time and someone saw something that concerned them regarding his overall health. When they saw the medical report, the Pirates lost interest. For his part, Shanks went home, to prepare for death or one of the greatest comebacks of all time. He went on to play 14 seasons of major-league baseball and, though he died at the relatively young age of 51, it would be safe to agree with Shanks that “Either that doc didn’t know his business or Monaca is some health resort.”1

“My boy, prepare for the finish. You ain’t got more than a couple of weeks to live.” That is what a doctor told Howard Shanks in 1910. Shanks was told he had consumption (tuberculosis). He had just finished his second year of professional baseball, playing at East Liverpool, Ohio. Barney Dreyfuss of the Pittsburgh Pirates was interested in him, but Shanks only weighed 130 pounds at the time and someone saw something that concerned them regarding his overall health. When they saw the medical report, the Pirates lost interest. For his part, Shanks went home, to prepare for death or one of the greatest comebacks of all time. He went on to play 14 seasons of major-league baseball and, though he died at the relatively young age of 51, it would be safe to agree with Shanks that “Either that doc didn’t know his business or Monaca is some health resort.”1

Monaca, Pennsylvania, is where Shanks repaired after receiving the diagnosis. It was home. There were 3,376 people living in Monaca in 1910, a borough in Beaver County, located on the Ohio River about 25 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. Though Shanks was born in Chicago on July 21, 1890, his family moved to Monaca when he was a boy. His father Samuel Shanks, a native of County Tyrone, Ireland, came to the United States in 1881. He and his wife Elizabeth (Oatey) moved first to Youngstown, where he worked as an iron puddler in 1900. They had five children. Howard was the second-born.

Samuel Shanks may have died; by 1910, Elizabeth was married to John C. Smith – also a puddler – a native of Germany, who had immigrated in 1885. Three of her children, including Howard, were listed at the Monaca address.

Howard reported, in his player questionnaire, attending Monaca schools all the way through. His first baseball was semipro ball with the Monaca Regulars in 1907. In 1908, he played for the Rochester Athletics team in Beaver, a team run by former Pirates outfielder Thomas McCreery, and with the Beaver Valley Athletics. It was on McCreery’s recommendation that the East Liverpool Potters team (Ohio-Pennsylvania League) signed Shanks. He hit .240 his first year, 1909, and the Potters finished second, by three games, in the eight-team Class C league. The next season, he hit .223, and East Liverpool finished in third place. Each year, Shanks played in over 100 games. But something prompted Pittsburgh to ask that he be looked over medically. His contract was sold to Youngstown, one of eight East Liverpool players sold to the rival Ohio-Pennsylvania League club.

In 1911, having survived the diagnosis, and put on about 40 pounds, he played for the second-place Youngstown Steelmen and hit .291 with nine homers in 124 games, while committing only three errors. Clearly, he was healthy. He stood 5-feet-11 and is listed as weighing 170 pounds. As early as May, he was being looked over by Jimmy McAleer. “The lad is about the best young outfielder I have seen this year…I had been tipped off some time ago to this player, and so I thought I’d go down and look him over. The lad is marvelously fast in the field and seems to know just what to do with himself. I can have him if I want him, and most likely I’ll take him, too, after a few weeks.”2 McAleer was unable to act right away, because Shanks was so popular with Youngstown fans that manager Bill Phillips did not want to let him go.3 Besides, it was reported, Shanks didn’t want to go to Washington. Other scouts and baseball people expressed interest, too, such as John McGraw of the Giants.4 The Pirates became interested again, too.

The Washington Senators drafted him in the September 1 Rule 5 draft. Mike Kahoe is credited with the actual signing; he worked as Washington’s main scout at the time. The Senators anticipated using Shanks in a utility role–or maybe not to use him at all. McAleer hailed from Youngstown and (it was written nearly a year later) he drafted Shanks to keep him from going to another team and then return him to Youngstown in the spring–in other words, to “cover him up.” But McAleer became a part-owner of the Boston Red Sox and Clark Griffith bought into the Senators. “When Griff looked over his youngsters this spring, he could not see anything the matter with Shanks except inexperience, so decided to keep him.”5

His debut came on May 9, 1912, pinch-hitting for Dixie Walker, but made an out. Shanks got more work than initially expected (he ultimately played in 116 games) and by early August was said by the Washington Post to be “playing the best left field in the league.”6 He was a gamer, for sure. In the springtime he’d been beaned in batting practice and been out for a week or two. When he was hit again–hard–in the head on August 1, by a George Mullin fastball, “he fought the players of the two clubs who ran to the plate and tried to carry him. It required the services of about four athletes to hold Shanks’ legs and arms, while four others did the actual lugging.”7 He was dizzy in the dressing room, but recovered later in the day.

The Red Sox won the pennant, by 14 games over the Senators, who beat out the third-place Athletics by two games. Shanks drove in 48 runs and scored 25; he hit for a .231 average (.305 on-base percentage). He was a very good fielder who earned his keep with defense. Griffith later said that “the greatest play I ever saw was pulled off by one of my own boys–young Howard Shanks. That kid actually came in from the outfield, gathered up an error, carried it into the infield and converted it into a double play. I might add in passing that the stunt retired the side, and saved the game for us.”8 Shanks was playing left field that day against the White Sox, but he recorded a putout at second base, tagging baserunner Harry Lord and then threw to home plate in time to get Morrie Rath trying to score.9

He was rated an “ordinary hitter” but was “one of the few outfielders who frequently take part in infield plays” because he learned the art of positioning better than most.10 Numerous stories over his early years–accurately or otherwise–rated him as tops among left fielders in the game.

Shanks improved to .254 in 1913, despite what at first seemed like a broken foot (but was not) and then a turned ankle in mid-September. This season was the closest the Senators came to contending during his 11 seasons with Washington years; they finished in second place, 6 1/2 games behind the Athletics. After the season, the famous Bonesetter Reese of Youngstown found a dislocated tendon in Shanks’s ankle and manipulated it back into position.11

Howard Shanks married Wilhelmina Wagner on February 24, 1915.

Through 1916, Shanks played almost exclusively as an outfielder. But, in 1916, he played six different positions, though primarily left field (71 games) and third base (31 games). Already in September 1916, Griffith started talking about using Shanks regularly at shortstop. He did just that in 1917, and Shanks appeared in 90 games at short against just 26 in the outfield. He also played a couple of games at first base. By the end of his career, the only positions he had never played were pitcher and catcher.

One role he was never called to perform was military service. He was not exempted and appears on the lists of major leaguers subject to the “work or fight” order, nor does he seem to have been assigned to any defense-related work.

His batting averages fluctuated around .240 for his first eight seasons with Washington, but in 1920 he hit for a .268 average (his best to that date) and hit four homers (matching the four he’d hit in 1914). He topped both figures, by a big margin, in 1921. It was his career year, perhaps also reflecting the livelier baseball. Shanks hit .302, knocked out seven home runs, and led the league with 18 triples. The most triples he’d hit before was also in 1914, with 10. He established career highs with 69 RBIs and 81 runs scored.

The Red Sox had talked trade with Griffith for a couple of years, and continued to do so. A broken finger in 1922 cost Shanks a number of games in April and May, and new manager Clyde Milan simply didn’t use him as much, but he still hit for a strong .283 average (.352 OBP), and remained an attractive trade target.

In February, a deal was struck. Three players–Ed Goebel, Val Picinich, and Shanks–went to the Red Sox for Muddy Ruel and Allen Russell. The Sox planned to use Shanks as the versatile utility man he was. He primarily played second base and third base, and hit for a .254 average–just about the same as the .252 he’d hit over his 11 seasons with the Senators. He drove in 57 runs in 131 games.

In 1924, the year a now-dominant Senators team won the pennant and the World Series, Shanks was used in fewer than half the season’s games. He appeared in 72 games for Boston, though producing just as in 1923: a .259 average and 25 RBIs. On December 10, he was traded to the Yankees for Mike McNally.

His work for New York in 1925 was almost the same as for the Red Sox in 1924: 66 games, .258, though with only 18 runs batted in. He was released in December and his days in the major leagues were over.

Shanks played two more years of minor-league ball before hanging up his spikes: in 1926 and in part of 1927, he played for the American Association’s Louisville Colonels. During 1927, he moved to Rochester (International League), where he wrapped up his playing career. His major-league career line: 1,665 games, a .253 batting average (.308 OBP), with 620 RBIs, and a lifetime .950 fielding percentage (his 25 games at first base represent the smallest number he played at any position).

For the next five seasons (1928 through 1933), Shanks worked as a coach for manager Roger Peckinpaugh‘s Cleveland Indians.

And then, just for the one year, he worked in 1938 as manager of the Beaver Falls Browns (Class D Pennsylvania State Association). In 1939, Peckinpaugh managed the New Orleans Pelicans and again hired Shanks as his coach.12

For the last year of his life, from June 1940, Shanks worked in the real estate department of Beaver County. He had always been active in community affairs in Monaca, with the Lutheran Church, Boy Scouts, Red Cross, Salvation Army, Masonic Order, Knights of Pythias, etc.

Shanks died of a coronary occlusion on July 30, 1941. He was entertaining family and his pastor on the porch at his home. He excused himself for a few moments, went into the living room, and died. He had just remarked, that very day, that he had never felt better in his life.

He was survived by Wilhelmina, two sisters, and one brother. The couple had no children.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Shanks’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, March 14, 1915. The story ran nationally and appeared in many newspapers. Another rendition of the doctor’s remarks read “Outside of having a very bad case of consumption, you are all right, and if the fatal illness you have permits you to linger longer than three months I will be very much surprised.”

2 The Repository (Canton, Ohio), May 28, 1911.

3 The Repository (Canton, Ohio), June 6, 1911.

4 Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 12, 1911.

5 Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, August 4, 1912.

6 Washington Post, August 2, 1912.

7 Ibid.

8 Washington Evening Star, April 27, 1913. Within this article, Griffith recounts the play in detail.

9 The Sporting News, December 7, 1922.

10 Washington Evening Star, April 17, 1914.

11 Washington Evening Star, November 13, 1913.

12 New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 5, 1939.

Full Name

Howard Samuel Shanks

Born

July 21, 1890 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

July 30, 1941 at Monaca, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.