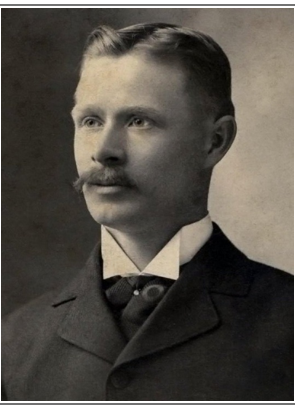

Bill Phillips

Bill Phillips’s professional baseball career spanned a quarter century from 1890 to 1915. A right-handed pitcher, he was a five-time 20-game winner in the minors and pitched for the Cincinnati Reds for six seasons. A smart and respected baseball man, Phillips managed several teams, most notably the Indianapolis Hoosiers, champions of the Federal League in 1914. Among the players he mentored were future Hall of Famers Bill McKechnie and Edd Roush.

Bill Phillips’s professional baseball career spanned a quarter century from 1890 to 1915. A right-handed pitcher, he was a five-time 20-game winner in the minors and pitched for the Cincinnati Reds for six seasons. A smart and respected baseball man, Phillips managed several teams, most notably the Indianapolis Hoosiers, champions of the Federal League in 1914. Among the players he mentored were future Hall of Famers Bill McKechnie and Edd Roush.

William Corcoran Phillips was born on November 9, 1868, in Allenport, Pennsylvania, south of Pittsburgh. He was the only child of Thomas and Sarah Josephine (Furnier) Phillips.1 Thomas was a coal miner who died at the age of 21, presumably in a mining accident, when Sarah was 17 and William was two years old. Sarah remarried four years later, to John Wolfe.2 To help make ends meet, William worked in the coal mines, beginning at age seven.3 Child labor was common at that time.

Baseball gave William an opportunity to escape from a harsh life in the mines. As a strapping young man — 5’11” and 170 pounds — he pitched on the sandlots of Fayette City, near Allenport, where he was recruited by scout Ted Sullivan to pitch for the 1890 Washington Senators of the Atlantic Association.4 Phillips posted a 17-16 record for the Senators, before the team disbanded on August 2.5

Sullivan introduced Phillips to Guy Hecker, manager of the Pittsburgh Alleghenys, the weakest team in the National League, and Phillips was hired to pitch for the club. He made his major-league debut in Pittsburgh on August 11, 1890, against Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts. The Alleghenys had won only two of their previous 31 games, but on August 11, they were “full of dash and spirit”6 as they defeated the Colts, 6-4. Phillips impressed observers with the speed of his fastball, but this game would be his only major-league victory of the season. Five days later in Chicago, the Colts assailed his offerings in an 18-5 massacre. In the fifth inning, the Colts scored 13 runs, including eight runs brought home by a pair of grand slams clouted by Tom Burns and Malachi Kittridge. “Run after run crossed the plate and base hits followed each other with bewildering rapidity,” reported the Chicago Tribune.7 Besides Phillips, only one pitcher, Chan Ho Park, had surrendered two grand slams in one inning of a major-league game through 2017.

Phillips’s 1-9 record for the Alleghenys mirrored the team’s ineptitude. In Boston on August 25, the Beaneaters collected 18 hits off him in a 15-2 thrashing, as his bumbling teammates committed nine errors.8 At Canton, Ohio, on September 18, Phillips and the Alleghenys were edged 11-10 by the Cleveland Spiders and their rookie pitcher, Cy Young; it was Young’s sixth major-league victory.9 The woeful Alleghenys finished the 1890 season with a 23-113 record.

Phillips pitched for a Meadville (New York) team in 1891. The following year he joined Ted Sullivan’s Chattanooga Chatts of the Southern League and was one of the league’s finest hurlers. His 21-16 record for the 1892 Chatts included six shutouts. He threw a no-hitter against Memphis on June 7, and he defeated Memphis again with a one-hit shutout on July 28.10 Sporting Life called him “Cyclone” Phillips,11 and during his career he acquired many more nicknames, including Big Bill, Silver Bill, Whoa Bill, Blond Bill, Honest Bill, Silent Bill, and Allenport Bill.

In 1893 Phillips pitched for teams in five cities — Nashville, Owensboro (Kentucky), Akron (Ohio), Memphis, and Johnstown (Pennsylvania) — and the next year he joined the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Western League. In three games in early May of 1894, he surrendered a total of 63 runs,12 and it appeared that he could not compete at this level. But after making adjustments, he put together a respectable season for the Hoosiers, highlighted by a four-hitter against Minneapolis on the Fourth of July and a three-hit shutout of Detroit on August 6.13 He compiled a 26-21 record in 421 innings, the third most innings pitched in the league, and he proved to be an excellent hitter with a .371 batting average in 213 at-bats. After he beat the Cincinnati Reds with a four-hitter in a September exhibition game, the Reds signed him to a contract for the 1895 season.14

Bothered by arm trouble, Phillips pitched unimpressively for the 1895 Reds, with a 6-7 record and a 6.03 ERA in 109 innings. He was farmed out to the Hoosiers at the end of July, and his 12-4 record down the stretch helped the Hoosiers win the Western League pennant.

Over the next three seasons, Phillips was an ace of the Indianapolis pitching staff. His combined won-lost record from 1896 to 1898 was 72-28. The 1897 Indianapolis team won the Western League title by a large margin, and on the last day of the season with the pennant already clinched, Phillips pitched against the Detroit Tigers while smoking his “long corncob pipe” and beat them, 9-3.15 “He filled the diamond with smoke,” said Mike Kahoe, the Indianapolis shortstop.16 Indeed, there was smoke from Phillips’s pipe and from his fastball.

Phillips was especially sharp near the end of the 1898 season. He defeated the Minneapolis Millers with a one-hitter on August 20; beat the Columbus (Ohio) Senators with a two-hitter on September 3; and shut out Connie Mack’s Milwaukee Brewers on September 5.17 He clearly demonstrated that he was ready to return to the major leagues, and at age 30, he was given another chance by the Cincinnati Reds.

On April 29, 1899, Phillips tossed a five-hit shutout as the Reds defeated the Chicago Orphans, and he beat the Orphans with another five-hitter on June 14.18 “There are no better pitchers than Bill Phillips,” said Sam Mertes of the Orphans. “I saw enough of him in the Western League to know that he can pitch ball in any company. He is nothing short of a wonder.”19 The Orphans’ Jimmy Callahan concurred. Phillips “has as much speed as any man I ever batted against, and his curve balls break just at the right place,” said Callahan. “I don’t know of a better pitcher.”20 Phillips achieved a 17-9 record for the 1899 Reds, and the Cincinnati Enquirer said he has the potential to become the next Kid Nichols, Amos Rusie, or John Clarkson.21

Phillips utilized a full repertoire of pitches. Besides his fastball and curveball, he threw a changeup that was described as “superlatively deceptive,” and with a submarine motion he delivered an “underhand curve” and an “underhand raise.”22 He also threw an emery ball,23 and he may have been the first to throw a blooper or eephus pitch.24

By a 5-4 margin on May 6, 1900, Phillips and the Reds defeated Cy Young and the St. Louis Cardinals, despite Young’s three-run homer in the second inning.25 On July 13, Phillips beat the Cardinals again by twirling a 10-inning, five-hit shutout.26 Twice he shut out the first-place Brooklyn Superbas during the 1900 season, on August 13 and again on September 14.27 But his 9-11 season record was disappointing. Sporting Life reported that “malaria rendered him ineffective at various stages” of the season.28

On August 17, 1900, Phillips lost his cool on a 90-degree day in Cincinnati while pitching to Roy Thomas of the Philadelphia Phillies. Trying to get a base on balls, Thomas deliberately “fouled off ten balls or more.”29 He was known for this trick; he “had the practice of turning good strikes into mere fouls so perfected that he could take his usual cut at the ball and, getting a piece of it, foul it straight over the catcher’s shoulders.”30 After umpire Bob Emslie ignored Phillips’s protest, Phillips punched Thomas, knocking him to the ground. Emslie then ejected Phillips, who quickly and sincerely apologized. In 1901, the National League introduced the foul-strike rule, whereby a foul ball with fewer than two strikes is counted as a strike, to discourage the tactic employed by Thomas.31

After turning down offers to jump to the American League in 1901, Phillips pitched erratically for the Reds and the team landed in the cellar of the National League. It seems he lost something on his fastball; it lacked “the requisite steam” to be effective, said Sporting Life.32 In the second game of a doubleheader on June 24, the Phillies pounded him for 19 runs, and the next day a concise headline in the Cincinnati Enquirer summed it up: “Phillips Slaughtered.”33 In another disaster, on September 24, Brooklyn scored 16 runs off him.34 He finished the season with a 14-18 record and a 4.64 ERA (the league ERA was 3.32), and gave up the most earned runs of any National League pitcher.

But Phillips and the Reds rebounded in 1902. The team finished in fourth place with a 70-70 record, and Phillips posted a 16-16 mark. His 2.51 ERA was better than the league average of 2.78, and he demonstrated his hitting prowess with a .342 batting average in 114 at-bats. On May 13, he and the Reds turned the tables on the Phillies, crushing them in a 24-2 rout. In addition to his splendid pitching, Phillips smacked a triple and three singles that day and scored three runs. “Phillies Led to Slaughter by Reds” was the headline in the Philadelphia Inquirer.35

Phillips and the Reds twice defeated Christy Mathewson and the New York Giants in 1902, by a score of 6-1 on May 17, and by a 10-2 margin on July 15.36 Phillips had learned to pitch with his head and not with his arm. He understood the strengths of the batters and took advantage of their weaknesses. “Speed and a good assortment of curves are a great thing for a pitcher,” he said, “but eventually his arm will weaken and his wrist lose its cunning.”37 At that point, a pitcher’s brain is his greatest asset.

For much of the 1903 season, Phillips was sidelined by leg injuries, and after the season he was released by the Reds at his request.38 In 1904 he was playing manager and co-owner of the Indianapolis Indians,39 who finished in sixth place in the eight-team American Association. For the next three seasons, he pitched for the New Orleans Pelicans in the Southern Association.

Phillips’s 21-8 record for the 1905 Pelicans included eight shutouts. On April 30, 1906, the 37-year-old hurler went the distance in a 13-inning pitchers’ duel with 21-year-old Gordon Hickman of the Shreveport Pirates; the game ended in a 1-1 tie.40 A year later, on May 4, 1907, Phillips fired a two-hit shutout to win a 1-0 duel against Hickman and the Pirates.41 The old man could still pitch.

Phillips and George Suggs had a different sort of rivalry in 1907. Suggs, while pitching for the Memphis Egyptians on July 9, “hit Pitcher Phillips a terrific rap on both wrists, and for ten minutes it looked as though Bill was down and out for the game. But there is not an ounce of blood in the old man’s veins that is not fighting blood,” and he remained in the game which ended in a 1-1 tie.42 Then, in the second game of a doubleheader on August 7, Phillips was again hit on the arm by a Suggs pitch. This time he threw his bat at Suggs and was ejected from the game.43

In 1908 Phillips was the playing manager of the East Liverpool (Ohio) Potters. The team was so named because East Liverpool was regarded as the Pottery Capital of the World. One of his teammates was his 32-year-old half-brother, pitcher Barney Wolfe. The Potters finished the season in second place in the eight-team Ohio-Pennsylvania League. At age 39, Phillips compiled an impressive 18-4 record. He threw a one-hit shutout against the Sharon (Pennsylvania) Giants on May 26; the sole hit, which came with two outs in the ninth inning, was a double by pitcher Henry Mathewson, Christy’s brother.44 After the Potters’ season ended, Phillips pitched in a few September games for the New Orleans Pelicans.45

The next season Phillips was the playing manager of the Wheeling (West Virginia) Stogies, and he guided the team to the 1909 Central League championship. In 162 innings pitched, he posted a 12-3 record, and opposing hitters batted only .201 against him.46 In the first game of a doubleheader on August 12, he threw a no-hitter against the South Bend (Indiana) Greens.47 One Stogie he mentored was Bill McKechnie, a 22-year-old infielder who in 1962 would be inducted into the Hall of Fame as a manager. Phillips “was a keen strategist from whom McKechnie learned plenty about how to get results out of the material at his command.”48

In 1910 Phillips again managed the Wheeling team and it was his final season as a pitcher. On May 7, he pitched 13 innings against the Dayton (Ohio) Veterans and scored the winning run in a 2-1 triumph.49 However, after winning the 1909 championship, his best players moved on to other teams, and with little material to work with, Phillips and the Stogies stumbled to a last-place finish in 1910. During the season, he instructed several future major leaguers on this team, including Bill Doak, Fritz Maisel, and Burt Shotton.

For the next two seasons, Phillips managed the Youngstown (Ohio) Steelmen and led them to consecutive second-place finishes. On the 1911 team, he mentored two young infielders, Everett Scott and Howie Shanks, who would both go on to successful major-league careers. In the winter of 1911-12, Phillips was stricken with typhoid fever and pneumonia,50 but he recovered.

Phillips returned to Indianapolis in 1913 and managed the Hoosiers, leading them to the Federal League championship in the first year of the league’s existence. The team won the pennant by a large margin, 10½ games ahead of the second-place Cleveland Green Sox, who were managed by Cy Young. The next year, the Federal League expanded from six to eight teams and declared itself to be a major league in direct competition with the American and National Leagues, and Phillips was again at the helm of the Indianapolis club.

The 1914 Hoosiers started slowly, with a 19-23 record through games of June 9, but they caught fire with a 15-game winning streak from June 11 to June 24 and moved into first place. They fell back to fourth place in early August, but from August 12 to August 26, they won 13 of 15 games and moved back into the lead. At the end of September, they were in second place, but they won their final seven games of the season to overtake the Chicago Federals and capture the pennant by a narrow 1½-game margin.

Phillips had assembled a potent lineup. As a team, the Hoosiers led the Federal League in batting average, runs scored, and stolen bases, and their team ERA was second best in the league. They were also the most disciplined team in the league, according to Ralston Goss, sporting editor of the Indianapolis Star.51 Phillips is “a man of many ideas” who is “extremely painstaking and patient,” said Goss.52

Phillips taught Hoosiers outfielder Benny Kauff to hit to all fields, and Kauff led the league in batting average (.370), runs scored (120), and stolen bases (75), and was called “the Ty Cobb of the Federal League.”53 The Hoosiers relocated to Newark, New Jersey, for the 1915 season, and in the process Phillips lost Kauff, who was assigned to the Brooklyn Tip-Tops to satisfy an Indianapolis debt to the Brooklyn club. But the departure of Kauff created a vacancy in the Newark outfield that was capably filled by 22-year-old Edd Roush.

After starting strongly with a 19-12 record through games of May 21, 1915, the Newark Peppers slumped, winning only seven of the next 22 games, and Phillips was fired by team owner Harry F. Sinclair. As a manager, Phillips was “exceedingly reserved and undemonstrative,” and had an “easy going way” with his players; what Sinclair wanted was a manager “who demands fire and dash and enthusiasm” from his team.54 Observers felt that Sinclair was foolish to fire the only manager to have won a pennant in the Federal League. Bill McKechnie, the Newark third baseman and a Phillips protégé, was named as the team’s new manager.

Phillips was content to leave professional baseball, and he lived in Charleroi, Pennsylvania, with his family and operated his bowling and billiard hall there. In 1894 he had married Mary C. Dinsmore, and they had three sons (William Jr., Lewis, and Thomas) and one daughter (Thelma).55 He briefly came out of retirement to manage the Charleroi Governors of the Middle Atlantic League for part of the 1931 season; his son Lewis was an outfielder on the team.

Phillips died in Charleroi on October 25, 1941, at the age of 72, and was buried at the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Fayette City.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Rob Wood.

Sources

Ancestry.com.

Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of an Outlaw Major League, 1914-1915 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009).

Notes

1 1870 US Census.

2 1900 US Census.

3 Buffalo Enquirer, August 20, 1902.

4 Ibid.

5 Baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Atlantic_Association.

6 Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 12, 1890.

7 Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1890.

8 Sporting Life, August 30, 1890.

9 Pittsburgh Daily Post, September 19, 1890; Reed Browning, Cy Young: A Baseball Life (Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000), 13-14.

10 Sporting Life, June 18 and August 13, 1892.

11 Sporting Life, March 4, 1893.

12 Indianapolis Journal, May 5, 8, and 11, 1894.

13 Sporting Life, July 14 and August 18, 1894.

14 Indianapolis Journal, September 12 and 26, 1894.

15 Detroit Free Press, September 22, 1897.

16 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 23, 1900.

17 Sporting Life, August 27, September 10 and 17, 1898.

18 Sporting Life, May 6 and June 17, 1899.

19 Detroit Free Press, April 20, 1899.

20 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 21, 1899.

21 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 25, 1899.

22 Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, September 6, 1899; Cincinnati Enquirer, August 14, 1900; Pittsburgh Press, July 25, 1901.

23 Pittsburgh Press, August 18, 1917.

24 John Thorn and John Holway, The Pitcher (New York: Prentice Hall, 1987), 153.

25 Sporting Life, May 12, 1900.

26 Sporting Life, July 21, 1900.

27 Sporting Life, August 18 and September 22, 1900.

28 Sporting Life, October 27, 1900.

29 Sporting Life, August 25, 1900.

30 The Sporting News, February 5, 1925.

31 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 62.

32 Sporting Life, May 11, 1901.

33 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 25, 1901.

34 Minneapolis Journal, September 25, 1901.

35 Philadelphia Inquirer, May 14, 1902.

36 Sporting Life, May 24 and July 26, 1902.

37 Mansfield (Ohio) News-Journal, September 27, 1902.

38 Pittsburgh Daily Post, October 2, 1903.

39 Fort Wayne (Indiana) Daily News, November 3, 1903.

40 Sporting Life, May 12, 1906.

41 Sporting Life, May 18, 1907.

42 New Orleans Times-Democrat, July 10, 1907.

43 Sporting Life, August 17, 1907.

44 East Liverpool (Ohio) Evening Review, May 27, 1908.

45 John A. Simpson, The Greatest Game Ever Played in Dixie: The Nashville Vols, Their 1908 Season, and the Championship Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 163.

46 Sporting Life, February 19, 1910.

47 Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, August 13, 1909.

48 The Sporting News, February 20, 1941.

49 Indianapolis Star, May 8, 1910.

50 Sporting Life, December 30, 1911.

51 Indianapolis Star, October 7, 1914.

52 Indianapolis Star, March 29, 1914.

53 Sporting Life, July 25, 1914; Allentown (Pennsylvania) Democrat, December 20, 1916.

54 Sporting Life, June 26, 1915; F.C. Lane, Baseball Magazine, August 1915.

55 William C. Phillips, Jr., managed the 1928 Charleroi Babes of the Middle Atlantic League, and his brother Lewis was a member of the team.

Full Name

William Corcoran Phillips

Born

November 9, 1868 at Allenport, PA (USA)

Died

October 25, 1941 at Charleroi, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.