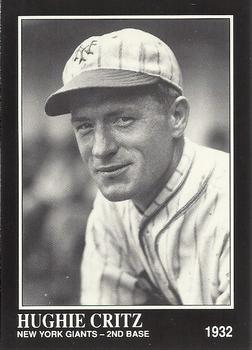

Hughie Critz

When The Sporting News profiled baseball’s greatest second basemen in 1929, four photos appeared at the top of the page: Rogers Hornsby, Eddie Collins, Frankie Frisch, and Hughie Critz.1

When The Sporting News profiled baseball’s greatest second basemen in 1929, four photos appeared at the top of the page: Rogers Hornsby, Eddie Collins, Frankie Frisch, and Hughie Critz.1

As Sesame Street teaches us, one of these things is not like the others. Hughie Critz hit over .300 only once, never reached double figures in home runs, never weighed more than 150 pounds or topped 5-foot-8.

Hornsby dominated the National League leader board with his bat, Critz with his glove. Critz (rhymes with “bites”) led the league in major fielding categories 19 times. The Giants’ John McGraw called him the best in the game.2 McGraw tried to acquire him for two years before he closed a deal.

The son of a college president, Critz didn’t set out to be a ballplayer. “As a matter of fact,” he said, “I did not care about baseball until I had been playing professionally for several years.”3 He walked away from the game at 35 and spent the second half of his life as a plantation owner and businessman.

Hugh Melville Critz was born in Starkville, Mississippi, on September 17, 1900, the first of three children of Hugh and Julia Gillespie Critz. His father, known as Colonel Critz, served as president of the Arkansas College of Agriculture, now Arkansas Tech University; Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College, which was renamed Mississippi State during his tenure; and Arkansas A&M.

The son, called Melville, didn’t go out for baseball until his junior year at Mississippi A&M. He followed his father as shortstop and captain of the varsity team, but the senior Critz was not happy about it. “I spent five years getting through college because I played baseball,” the colonel said, “and now my boy thinks that’s what he wants to do.”4

After graduation in 1920 — in four years — young Hugh entered his chosen profession as a cotton broker for a firm in Greenwood, Mississippi. He started his career just in time for a farm depression that sent cotton prices plunging. He had been playing ball for a local semipro team and quit the failing brokerage business when the club joined the Class D Mississippi State League in 1921.

He batted .299 while playing third base, and the Greenwood club sold him to Class A Memphis for $2,000 after the season. Critz agreed to go in return for half of the purchase price. During the winter he married Mary Wiggs of Russellville, Arkansas.

Critz moved up to the highest minor-league level at Minneapolis in 1923. Shifted to shortstop, he broke out as a star with a .326 batting average. The next spring the Cincinnati Reds were trying to work out a deal when a line drive dislocated Critz’s left thumb. Soon after he returned to the lineup, Cincinnati acquired him for a reported $15,000 plus several players.

The Reds needed Critz to fill a hole at second base. He joined the team in Chicago on May 31 and started the first big-league game he had ever seen. He singled twice off Grover Cleveland Alexander in his debut, beginning a run toward the best offensive season of his career. The rookie batted .322 in 102 games with an .800 on-base plus slugging percentage. Touted as one of the fastest players in the league, he legged out 14 triples and stole 19 bases.

His glove drew rave reviews. In 1925 his 2.5 defensive wins above replacement was the best in the league for players at any position, the first of three times he led in that category.5 He led the league’s second basemen in fielding percentage five times, assists and double plays four times, putouts and range factor twice. One overwrought sportswriter described him as “a veritable leaping gazelle out there in the infield.”6

It was no accident that Critz gained a reputation as a smart player. “Such stars as Johnny Evers and Eddie Collins had set the fashion and brains and second base sort of went together,” he explained. “So I decided to appear smart, too. I shifted to the right for this batter, to the left for that one, guessed wrong half the time but got away with it.”7

His bat was another story. After his sterling rookie year, his production was below average for the rest of his career. He blamed God: “The good Lord takes you up to the plate and then leaves you flat.”8 Critz stood in the right-handed batter’s box with his feet spread wide and his hands a few inches apart. He copied the style from Ty Cobb, without Cobb’s results.9

Critz turned in his best all-around season in 1926 as the Reds fought the Cardinals for the pennant. His 588 assists set a major-league record for second basemen, and he also led the NL in double plays and fielding percentage. At the plate, he posted career highs with 41 extra-base hits and 79 RBIs while batting either first or sixth in the lineup, although his .687 OPS was the weakest among the club’s everyday players. The Reds finished second, just two games behind St. Louis, and Critz finished second to Cardinals catcher Bob O’Farrell in the sportswriters’ voting for most valuable player (then called the League Award).

With a performance that placed him among the game’s elite, Critz wanted an elite salary, a reported $20,000. The Reds offered half as much. He held out through spring training as fans signed petitions demanding that the club meet his price. After Cincinnati lost four of its first five games, Critz signed for a reported $12,000.10 But his season was shortened by injuries that limited him to 113 games.

Critz bounced back in 1928 with another standout year that earned him a fourth-place finish in League Award voting. He raised his batting line to .296/.335/.387. He and shortstop Hod Ford got most of the credit when the Reds set a NL record by turning 194 double plays. “Of course,” Critz said later, “the fact that we had sinker-ball and breaking-ball pitchers like Carl Mays, Adolph [sic] Luque, Red Lucas and Eppa Rixey helped us get all those ground balls.”11

One of Critz’s best friends in the game knocked him out of the lineup in mid-1929. The Cubs’ Riggs Stephenson, a former University of Alabama fullback, broke up a double play with a hard slide on July 2, sending Critz to a hospital with a knee injury. The play ignited a fight on the field that spilled over to the Chicago railroad station. As the two teams were waiting for their trains, they renewed the argument, and the Cubs’ Hack Wilson slugged Cincinnati pitcher Pete Donohue. Wilson was suspended for three days. Critz couldn’t play for six weeks.

By this time his reputation as the league’s top defensive second baseman was secure. The Draper-Maynard Co. called him the “Keystone King” in ads for its Hugh Critz-model glove.12 He was also well known for his many superstitions. A compulsive groundskeeper, he stuffed his pockets with pebbles, dead grass, and scraps of paper. Every time he took the field, he moved the opposing second baseman’s glove (players left their gloves on the field when they went in to bat). Frankie Frisch tormented him by carrying his own glove into the dugout, forcing Critz to run after him to touch it.13

John McGraw had tried repeatedly to acquire Critz for the Giants, but McGraw and Cincinnati manager Jack Hendricks were old enemies and never could agree on a deal. After Hendricks was fired at the end of the 1929 season, McGraw opened negotiations with the Reds’ new manager, Dan Howley. In May 1930 McGraw got his man. He traded a former 25-game winner, Larry Benton, for Critz.

With Critz joining first baseman Bill Terry, shortstop Travis Jackson, and third baseman Fred Lindstrom, McGraw thought he had the best infield in the league. He installed Critz as the leadoff man in front of Freddy Leach, Lindstrom, Terry, and Mel Ott, who all batted over .320 in the Year of the Hitter. Critz hit only .265, but scored 93 runs in 124 games with the Giants.

“McGraw would do anything to win,” Critz said. “We got along, because if I hadn’t gotten along with McGraw, I wouldn’t have been with the Giants.” In an interview decades later, he added that the manager “didn’t have as bad a temper as some sportswriters tried to say he did; he just wanted to win.”14

A sore throwing shoulder in 1931 threatened to end Critz’s career. He went home in August after playing just 66 games. The Giants didn’t offer him a contract for 1932 until he came to spring training and proved he was able to play.

He bounced back with a strong season, keeping his batting average above .300 for much of the summer before tailing off to finish at .276/.313/.355. He set another record for second basemen by handling 197 consecutive chances without an error. But the team fell to last place in June, and McGraw resigned after 30 years as manager. Critz welcomed the appointment of Bill Terry, whom he called one of the finest men he knew in baseball, as McGraw’s successor.15

By the time spring training opened in 1933, Terry had turned over more than half the roster. He put two young pitchers, Hal Schumacher and Roy Parmelee, in the starting rotation with veterans Carl Hubbell and Freddie Fitzsimmons, and traded for a top defensive catcher, Gus Mancuso. When Travis Jackson was slow to recover from surgery on both knees, Critz got a new double-play partner, rookie Blondy Ryan.

The new-look Giants took over first place in June. Critz was struggling to keep his batting average above .200, and Ryan was no better, but the team was winning with the league’s best pitching and defense. Hubbell’s 1.66 ERA was the best since the Deadball Era. Critz came alive in the final month. He hit .345 down the stretch as New York held off the Pirates and Cardinals to win its first pennant since 1924. The Giants defeated the Washington Senators in five games to claim the World Series championship.

Although Critz’s bat had become a clear liability, he turned in two of his best defensive seasons in 1933 and 1934. He led all NL fielders both years in defensive wins above replacement and led second basemen in range factor per game, assists, and fielding percentage.

The Giants appeared to be sailing to their second straight pennant in 1934 until a September slump brought them down. The archrival Dodgers beat them in the final two games to hand the flag to the Cardinals. After the season, a disappointed Terry announced that everyone on the roster was for sale or trade, excepting only Hubbell and Ott. Asked about Critz and his .242 batting average, the manager said, “We’re counting on him again.”16

But Critz was finished. A spike wound in his finger became infected and kept him out of the lineup for all of April 1935. When he returned, he competed for playing time with veteran Mark Koenig and rookie Al Cuccinello. Koenig was slow in the field, and Critz and Cuccinello were weak at bat. Playing only 65 games, Critz hit .187/.198/.242.

After reaching his 35th birthday in September, he announced his retirement. “O, I could hang around the big league for another year or so,” he said, “but the long grind had me down this year and I guess I’ll hang up.”17

He went home to his 1,000-acre plantation outside Greenwood. Terry wanted him to manage his hometown Class C club, which Terry owned, but he turned down the job. Instead he opened Hugh Critz Motor Co., a Ford-Lincoln dealership.

Hugh and Mary raised two daughters, Alice and Mary Ann. He later headed a group of local investors who bought the Greenwood team from Terry, and for several years he was president of the Cotton States League franchise, by then a Dodger farm club. But the car dealership was his primary business. He became a civic leader in Greenwood, serving on the utilities commission and draft board. His friend Charlie Whittington described him as an expert marksman with a 30.06 rifle on their frequent hunting trips.18 Critz died at 79 on January 10, 1980.

Critz was elected to the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame. More than three decades after he was traded away from Cincinnati, fans chose him as the second baseman on the Reds’ all-time team, which was honored at ceremonies marking the centennial of professional baseball in 1969.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Photo credit

The Sporting News/Conlon Collection.

Notes

1 MacLean Kennedy, “Kennedy Tells of Game’s Greatest Second Basemen,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1929: 3.

2 Joe Vila, “Ruth Blazes Trail as Yankees Jump Into Thick of A.L. Fight,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1930: 1.

3 Harry T. Brundidge, “Critz Never Saw Major League Game Until He Played in One,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1929: 3.

4 Associated Press, “Father Roots for Critz,” New York Times, October 8, 1933: S8.

5 Wins above replacement calculated by Baseball-Reference.com.

6 “Myer’s Superior Work at Bat Gains Edge Over Critz,” Washington Post, September 24, 1933: 15.

7 John Drebinger, “Players of the Game,” New York Times, May 26, 1930: 26.

8 Brian Bell, “On the Sidelines,” Washington Post, December 21, 1929: 16.

9 F.C. Lane, Batting (repr. Cleveland: SABR, 2001), 4.

10 “Critz Buoys Hopes of Cincinnati Fans,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1927: 1.

11 Harry Merritt, “Former baseball player Hugh Critz, 79, dies at hospital,” Greenwood (Mississippi) Commonwealth, January 10, 1980: 1.

12 Ad, Boys’ Life, June 1930: 54.

13 Purser Hewitt, “Hew-It to the Line,” Jackson (Mississippi) Clarion-Ledger, March 29, 1973: 16.

14 Dudley Marble, “Critz recalls colorful major league stories,” Greenwood (Mississippi) Commonwealth, January 6, 1975: 7.

15 Ibid.

16 Associated Press, “Terry Says 12 Giants Are for Sale,” Washington Post, October 30, 1934: 17.

17 “Critz Expects to Lead Minor Team in 1936,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1935: 25.

18 Merritt, “Former baseball player.”

Full Name

Hugh Melville Critz

Born

September 17, 1900 at Starkville, MS (USA)

Died

January 10, 1980 at Greenwood, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.