Dolf Luque

Baseball was already a fixture on the Cuban scene by the early 1870s and it had arrived burdened with its own home-grown Cuban apostles and its own full-blown and home-spun creation myths. It is well documented that a pair of Havana-bred brothers named Guilló (often misspelled as Guillot) had returned from Mobile, Alabama’s Springhill College as early as 1864 with bats and balls stuffed in their luggage. Nemesio and Ernesto Guilló were soon organizing impromptu pickup matches among former schoolmates in the central Havana barrio of Vedado.

Baseball was already a fixture on the Cuban scene by the early 1870s and it had arrived burdened with its own home-grown Cuban apostles and its own full-blown and home-spun creation myths. It is well documented that a pair of Havana-bred brothers named Guilló (often misspelled as Guillot) had returned from Mobile, Alabama’s Springhill College as early as 1864 with bats and balls stuffed in their luggage. Nemesio and Ernesto Guilló were soon organizing impromptu pickup matches among former schoolmates in the central Havana barrio of Vedado.

Within a handful of summers (by 1871) the first native Cuban ballplayer – namely one Esteban “Steve” Bellán, who had earlier joined the college nine at Fordham College – had gained a toehold within the North American professional ranks as an infielder with the Troy (New York) Haymakers of the then “major-league” National Association. Although it would be another four decades (1911, to be precise) before any more Cubans followed Bellán into the true “big leagues” of the north, Havana was nonetheless already featuring its own professional circuit before the end of the 1870s, a mere two years after the founding of North America’s venerable and still-standing National League.

Yet despite this primitive-era debut of island baseball and the surprisingly early trickle of Cuban players northward, there was but a single Cubano who garnered even moderate attention in the US leagues during pro baseball’s initial three-quarters of a century. Racial barriers had almost everything to do with this, of course. The grandest of the early Cuban hurling and slugging phenoms were simply too black in skin pigment ever to penetrate America’s exclusively white-toned national sport during the race-driven eras of Adrian “Cap” Anson and Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

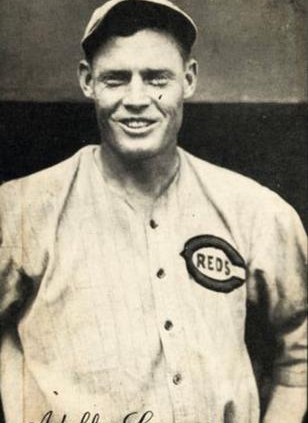

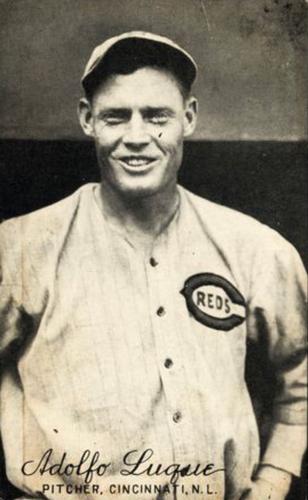

Thus just one lonely pioneer – Adolfo Luque (LOO-kay), a fireplug right-hander who debuted with Boston’s National Leaguers in 1914 and was already a veteran mound-corps mainstay with the Cincinnati club when the infamous 1919 Black Sox World Series rolled around – was left to carry the Cuban big-league banner throughout the half-century preceding World War II. Perhaps more embarrassing for Cuban baseball than the mere isolation of Luque’s big-league career was the persistent flavor of his negative image in Chicago, Boston, New York, St. Louis, and all points north. Unfortunately, this light-skinned if dark-tempered Cuban idol maintained a lasting reputation with big-league fans and ballpark scribes alike that was never quite as “fair and balanced” as most Cuban fans would have wished for back home.

Adolfo Luque today, of course, holds a rare place in Cuban baseball lore – the only Caribbean islander to earn even a modicum of big-league fame during the first half-century of modern major-league history. Between Nap Lajoie and Jackie Robinson, the few dozen Cubans who worked their way north were either brief curiosities in Organized Baseball (journeyman “coffee-tasters” like receiver Miguel Angel “Mike” González with the National League Boston and St. Louis outfits, and erratic outfielder Armando Marsans with Cincinnati) or else passing shadows who barely tasted the proverbial cup of big-league coffee (altogether forgettable names like Rafael Almeida, Angel Aragón, José Acosta, and Oscar Tuero). Numerous others – including some of the most famous and talented back home in Havana (Martin Dihigo, Cristóbal Torriente, and José Méndez head the list) – toured with black barnstorming outfits that rarely, if ever, passed before the eyes of the white baseball press.

By sharp contrast, Luque was something altogether special. His big-league credentials would by career’s end nearly approximate the numbers posted by many of his contemporaries destined for Cooperstown enshrinement once the game decided to formalize its history with a sacred hall of immortals. Twice (with the Reds in 1919 and the Giants in 1933) he experienced the pinnacle of World Series victory. As a near-200-game winner, he blazed trails that no other Latin ballplayer would approximate for decades. And back in Cuba he generated a feverish following for the big-league game and in the process carved out as well a lasting loyalty for “our beloved Reds” (“nuestros queridos rojos”) among baseball-crazy Habaneros. Yet, for all that, his career was destined to be cursed by the fate that eventually became a personal calling card for nearly all early Latin American ballplayers blessed with appropriate talent and skin tone to make their way to the baseball big-time. Among North American fans and writers Dolf Luque would always remain a familiar stereotype – a cartoon figure rather than a genuine baseball hero. At least this was the case at all stops north of Key West or Miami.

One incident above all others seems to have clinched the popular distortions. Perhaps the most spurious of apocryphal tales within the ample catalogue of legends that often substitute for serious baseball history is the one surrounding the fiery-tempered Luque, who eventually pitched a dozen seasons for the Roaring Twenties-era Cincinnati Reds. Legend has it that Luque, after taking a severe riding from the New York Giants bench, stopped in mid-windup, placed the ball and glove gingerly alongside the mound, then charged straight into the New York dugout to thrash flaky Giants outfielder Casey Stengel to within half an inch of his life.

This tale always manages to portray Luque within the strict parameters of a familiar Latin American stereotype – the quick-to-anger, hot-blooded, and somewhat addle-brained Latino who knows little of North American idiom or customs of fair play and can respond to the heat of combat only with flashing temper and flailing fists. The image has, of course, been reinforced over the long summers of baseball’s history by the unfortunate (if largely uncharacteristic) real-life baseball events surrounding the most notorious among Latin hurlers. Juan Marichal once brained Dodger catcher Johnny Roseboro with his Louisville Slugger when the Los Angeles receiver returned the ball to his pitcher (with the Giants ace at bat) by firing too close to Marichal’s head. The Giants’ Rubén Gómez was equally infamous for memorable head-hunting incidents featuring Brooklyn’s Carl Furillo and Cincinnati’s Frank Robinson. Gómez once plunked heavy-hitting Joe Adcock on the wrist, released a second beanball as the enraged Braves first sacker charged toward the mound, then retreated to the safety of the dugout only to return moments later wielding a lethal unsheathed switchblade knife.

The oft-told story involving Luque’s kamikaze mission against the Giants bench seems, in its most popular version, either a distortion or an abstraction of real-time events. Neither the year (it had to be between 1921 and 1923, during Stengel’s brief tenure with John McGraw’s club) nor circumstances are usually mentioned when the legend is related, and specific events are never detailed with any care. The true indiscretion here, of course, is that this story always seems to receive far more press than those devoted to the facts and figures surrounding Luque’s otherwise proud and productive 20-year big-league career. This was, after all, a premier pitcher of the early lively-ball era, a winner of nearly 200 major-league contests, the first front-line Latin American big-league ballplayer ever, and the first among his countrymen to pitch in a World Series, win 20 games in a single summer or 100 in a career, or lead a major league in victories, winning percentage, and ERA. Dolf Luque was, indeed, far more than simply the hot-spirited Latino who once, in a fit of temper, silenced the loquacious Charles Dillon Stengel.

For the record, the much ballyhooed incident involving Luque and Stengel does have its basis in raw fact. And like the Marichal-Roseboro affair four decades later, it appears to have contained details infrequently, if ever, properly reported. The setting was actually Cincinnati’s Redland Field (later Crosley Field) on the day of a rare packed house in midsummer of 1923. The overflow crowd – allowed to stand along the sidelines, thus forcing players of both teams to take up bench seats outside the normal dugout area –added to the tensions of the afternoon. While the Giants bench, as was their normal practice, spent the early innings of the afternoon disparaging Cincinnati hurler Luque’s Latin heritage, these taunts were more audible than usual on this particular day, largely because of the close proximity of the visiting team bench, only yards from the third-base line. Future Hall of Famer Ross Youngs was reportedly at the plate when the Cuban pitcher decided he had heard about enough from offending Giants outfielder Bill Cunningham, a particularly vociferous heckler seated on McGraw’s bench. Luque did, in fairness of fact, at this point leave both ball and glove at the center of the playing field while he suddenly charged after Cunningham, unleashing a fierce blow that missed the startled loudmouth and landed squarely on Stengel’s jaw instead. The unreported details are that Luque was at least in part a justified aggressor, while Stengel remained a totally accidental and unwitting victim.

The infamous attack, it turns out, was something of a humorous misadventure and more the stuff of comic relief than the product of sinister provocation. While the inevitable free-for-all that ensued quickly led to Luque’s banishment from the field of play, the now-enraged Cuban soon returned to the battle scene, again screaming for Cunningham and brandishing an ash bat like an ancient lethal war club. It subsequently took four policemen and assorted teammates to escort Luque from the ballpark a second time. Thus the colorful Cincinnati pitcher had managed to foreshadow both Marichal and Gómez –later club-wielding Latin moundsmen – all within this single span of intemperate high-spirited action.

Unfortunately, what originally passed for comic interlude had dire consequences in this particular instance. Luque had suddenly and predictably played a most unfortunate role in fueling the very stereotype that has since dogged his own career and that of so many of his countrymen. Yet, like Marichal, he was in reality a fierce competitor who almost always manifested his will to win with a blazing fastball and some of the cleverest pitching of his age. He was also a usually quiet and iron-willed man whose huge contributions to the game are unfortunately remembered today only by a diminished handful of his aging Cuban countrymen. So buried by circumstance are Luque’s considerable and pioneering pitching achievements that reputable baseball historian Lonnie Wheeler fully reports the infamous Luque-Stengel brawl in his marvelous pictorial history of Cincinnati baseball – The Cincinnati Game, with John Baskin – then devotes an entire chapter of the same landmark book to “The Latin Connection” in Reds history without so much as a single mention of Dolf Luque or his unmatchable 1923 National League campaign in Cincinnati.1

Unfortunately, what originally passed for comic interlude had dire consequences in this particular instance. Luque had suddenly and predictably played a most unfortunate role in fueling the very stereotype that has since dogged his own career and that of so many of his countrymen. Yet, like Marichal, he was in reality a fierce competitor who almost always manifested his will to win with a blazing fastball and some of the cleverest pitching of his age. He was also a usually quiet and iron-willed man whose huge contributions to the game are unfortunately remembered today only by a diminished handful of his aging Cuban countrymen. So buried by circumstance are Luque’s considerable and pioneering pitching achievements that reputable baseball historian Lonnie Wheeler fully reports the infamous Luque-Stengel brawl in his marvelous pictorial history of Cincinnati baseball – The Cincinnati Game, with John Baskin – then devotes an entire chapter of the same landmark book to “The Latin Connection” in Reds history without so much as a single mention of Dolf Luque or his unmatchable 1923 National League campaign in Cincinnati.1

It is a fact now easily forgotten in view of the near tidal wave invasion of Latin players during the 1980s and 1990s – especially the seeming explosion of talent flooding the majors from the hardscrabble island nation of the Dominican Republic – that before Fidel Castro shut down the supply lines in the early ’60s, Cuba had dispatched a steady stream of marginally talented athletes to the big leagues. After Esteban Bellán, an altogether average infielder with the Troy Haymakers and New York Highlanders of the 1870s National Association, the earliest National Leaguers were Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida, who both toiled briefly with the Cincinnati club beginning in 1911. (Marsans also had brief sojourns in the Federal League and with the American League New York ballclub.) After the color barrier was dismantled in 1947, the 1950s ushered in quality Cuban players as widely known for their on-field abilities as for their unique pioneering status – Sandy Amoros of the Dodgers; Camilo Pascual, Pete Ramos, Connie Marrero and Julio Bécquer with the Senators; Minnie Miñoso, Mike Fornieles, and Sandy Consuegra of the White Sox; Chico Fernández of the Phillies and Tigers’ Roman Mejías with the Pirates; Willie Miranda of the Orioles; and stellar lefty Mike Cuéllar, who launched an illustrious big-league pitching career (highlighted by the first Cy Young Award claimed by a Latin American native) with Cincinnati in 1959.

The best of the early Cubans, beyond the least shadow of a doubt, was Luque, a man who was clearly both fortunate beneficiary and ill-starred victim of racial and ethnic prejudices that ruled major-league baseball during his era. While dark-skinned Cuban legend Martín Dihigo was barred from the majors, the light-skinned Luque was quietly welcomed by management, if not always warmly accepted by the full complement of Southern mountain boys who staffed most big-league rosters.

Yet while Luque labored at times brilliantly in the big leagues during the second, third, and fourth decades of the past century, his achievements were always diminished in part because he pitched the bulk of his career in the hinterlands that were Cincinnati, and in part because his nearly 200 big-league victories were spread thinly over 20 years rather than clustered in a handful of 20-win seasons (he had only one such watershed year). And in the current Revisionist Age of baseball history writing – when Negro Leaguers have at long last received not only their belated rightful due, but a huge nostalgic sympathy vote as well – Martín Dihigo is now widely revered as a blackball icon and even enshrined within Cooperstown’s revered portals for his wintertime Cuban League and summertime Mexican League play, while Luque himself lies nearly obscured in the dust and chaff of baseball history.

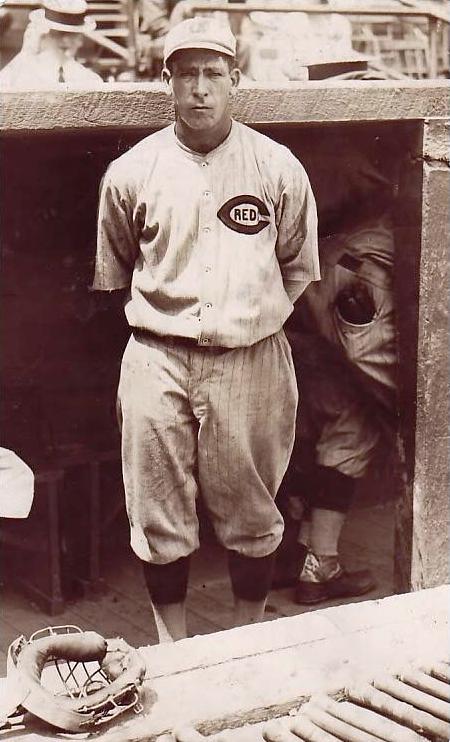

The memorable pitching career of Dolf Luque might best be capsulated in three distinct stages. Most prominent were the glory years with Cincinnati Reds throughout the full span of the Roaring Twenties, baseball’s first flamboyant and explosive decade after the pitching-rich but offense-poor Deadball Era. But first came the formative years of apprentice moundsmanship divided between two distinct baseball-oriented countries. Launching his professional career in Cuba in 1912 as both a pitcher and hard-hitting infielder, Luque displayed considerable talent at third base as well as on the hill. A mere six months after debuting with the Cuban League Fe club (0-4, but with three complete games) the promising youngster was promptly recruited by Dr. Hernández Henríquez, a Cuban entrepreneur residing in New Jersey and operating the Long Branch franchise of the New Jersey-New York State League.

A sterling 22-5 record that first New Jersey summer, along with a strange twist of baseball fate, soon provided the hotshot Cuban pitcher with a quick ticket to big-league fame. This was the epoch when professional baseball was still banned in New York City on Sunday, and thus visiting major-league clubs often supplemented sparse travel money by scheduling exhibition contests with the conveniently located Long Branch team on the available Sunday afternoon open dates. It was this circumstance that allowed Luque to impress Boston Braves manager George Stallings sufficiently to earn a big-league contract early in the 1914 season, the very year in which Boston surprisingly charged from the rear of the pack in late summer to earn a lasting reputation as the Miracle Braves – winners of an unexpected National League flag. In his debut with Boston, Dolf Luque became the first Latin American pitcher to appear in either the American or National League, preceding Emilio Palmero with the Giants by a single season and Oscar Tuero with the Cardinals by a full four campaigns.

Luque’s truncated “cup of coffee” in Boston was little beyond a blip on the radar screen of his eventual lengthy big-league sojourn and gave little signal of the personal triumphs and near-legendary moments that would lie ahead for the pioneering Cuban. Nor had he yet raised many eyebrows back on his native island, having at the time logged only three winter-league seasons in which he had appeared in a total of 15 games for the Fe and Habana clubs, posting three complete games and only two victories (both with Havana in the 1913-14 campaign), and boasting an unimpressive 2-8 ledger on the eve of his North American professional debut.

Stallings’ slow-starting Braves were still buried in the National League cellar when the 23-year-old Cuban rookie made his big-league debut on May 20 in Pittsburgh; the lackluster Beantowners had won only four of 22 outings at that point in the season. The initial outing was a moderate success to be sure, an eight-inning complete game 4-1 defeat that constituted more than 60 percent of Luque’s eventual 13⅔ innings of labor with the Boston club. He would make only one additional big-league appearance that summer (two-thirds of an inning). Of the dozen pitchers who labored for the eventual National League champions during the summer of Boston’s late-season “miracle” comeback, only two (Luque and southpaw Ensign Cottrell) failed to register a single victory on a staff paced by a pair of 26-win workhorses (Bill James and Dick Rudolph). By the time the club enjoyed its late-season surge and entered a fall classic showdown with the Philadelphia Athletics, the Cuban rookie was no longer part of the active pitching roster.2

Given a second shot with Stallings’ newly-crowned world champions in the spring of 1915, Luque again enjoyed a single early-season start alongside a second brief relief appearance; the total ledger consisted of five innings, no decisions, and a 3.60 ERA that stands as rather mediocre during the heart of the Deadball Era. Dropping to second place in the aftermath of their surprise pennant victory, the Braves used 13 different hurlers during the course of the 1915 campaign and Luque and veteran Gene Cocreham were the only pair to show zeros in both the win and loss columns. It would be three full years before the Cuban import (by then approaching his 28th birthday) would again savor a taste of North American big-league action.

Those brief appearances with Boston in 1914 and 1915 provided little immediate success for Luque, who soon found himself toiling with Jersey City and Toronto of the International League and Louisville of the American Association in search of much-needed minor-league seasoning. A fast start (six wins in 12 appearances) in the 1918 campaign brought on “stage two” for Luque – a permanent home in Cincinnati that would span the next dozen seasons. The Cuban fastballer was an immediate success in the Queen City, winning 16 games over the course of the 1918 and 1919 seasons, throwing the first big-league shutout by a Latin pitcher, and playing a major role out of the bullpen as the Reds copped their first-ever National League flag in 1919. Luque himself made history that fall of 1919 as the first Latin American native to appear in World Series play. He tossed five scoreless innings in two Series relief appearances while the underdog Reds outlasted Charlie Comiskey’s Chicagoans in the infamous Black Sox Series.

But it was Luque’s 1923 campaign that provided his career hallmark and that was, by any measure, one of the finest single campaigns ever enjoyed by a National League hurler during any epoch. Few moundsmen have so thoroughly dominated an entire league for a full campaign. Luque won 27 games while losing but 8, leading the circuit in victories, winning percentage (.771), earned-run average (1.93) and shutouts (6). The six shutouts could well have been ten—he had four complete-game scoreless efforts erased as late as the ninth inning. His 1.93 ERA would also not be matched by another Latin hurler until Luis Tiant registered an almost unapproachable standard of 1.60 in the aberrant 1968 season (the summer known as the Year of the Pitcher, when an entire league checked in with a 2.98 mark and five American Leaguers posted sub-2.00 figures). That same summer of 1923 Luque also became the first pitcher among his Spanish-speaking countrymen to bang out a major-league homer, while himself allowing only two opposition round-trippers in 322 innings, the second stingiest home run allowance ever for a pitcher in the National League and close on the heels of the 1921 standard of one homer in 301 innings pitched recorded by Cincinnati Reds teammate and eventual Hall of Famer Eppa Rixey.

One can best appreciate Luque’s 1923 performance merely by reviewing the day-in and day-out consistency of his remarkable summer-long craftsmanship. A game-by-game perusal reveals the Reds ace winning both of his decisions in April, standing 3-1 in May, 5-1 in June, 7-1 in July (including wins in both ends of a twin bill in Boston on July 17), 4-2 for the dog days of August, and 6-3 down the stretch run of September. So consistent was the Cuban’s overall performance that he registered 28 complete games (second in the league to Brooklyn’s Burleigh Grimes), paced the league with six shutouts, trailed only Grimes again in innings pitched (322 to 327), gave up the league’s fewest hits per nine innings pitched (7.8), yielded the lowest opponents’ batting average (.235), and outstripped the league’s second stingiest hurler by almost a full run per game (that being teammate Eppa Rixey, who owned a 2.80 ERA).

In the terms of John Thorn and Pete Palmer’s Total Pitcher Index (which rates a pitcher’s effective performance against that of the entire league), Luque’s 1923 campaign ranks fourth best in the two decades separating the century’s two great wars (1920-1940). Only Bucky Walters in 1939, Lefty Grove in 1931, and Carl Hubbell in 1933 outstripped Luque by the yardstick of the Thorn-Palmer statistical measure. Yet, despite Luque’s top-drawer performance (coupled with added 20-victory campaigns by teammates Eppa Rixey and Pete Donohue), Cincinnati nonetheless saw its pennant hopes slip away to John McGraw’s powerhouse Giants. It was the front-running New Yorkers who bested Luque in three of his eight losses (the other defeats coming at the hands of Chicago twice and Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh, each once). Havana’s pride and joy was especially devastating on opposing teams in their own home parks, winning a dozen decisions against a mere pair of road-trip setbacks registered in Chicago in late June and Pittsburgh in early September.

The 1923 season was a high-water mark never again to be equaled by the imported hurler today known back home as the Pride of Havana. Next in the evolution of Luque’s career came the dozen waning seasons as a fill-in starter, even if he was still a significant contributor with the Reds, Dodgers, and Giants. After losing 23 games with the second-place Reds in 1922 and then pacing the league in victories with the runner-up Cincinnati club of 1923, Dolf Luque would never again enjoy a 20-victory season, though he did come close to the milestone 20 total on both ends of the ledger (wins and losses) with a 16-18 mark (plus a league-leading 2.63 ERA) during the 1925 campaign. He did win consistently in double figures, however, over a ten-year span extending through his first of two brief seasons with Brooklyn at the outset of the 1930s. It is one of the final ironies of Luque’s career that while he was not technically the first Latin ballplayer with the Cincinnati Reds (following Marsans and Almeida in that role), he did actually hold this distinction with the Brooklyn Dodgers team which he joined in 1930. And while it was with the Reds that he had made his historic first World Series appearance, it was with the Giants a decade and a half later that he made a truly significant World Series contribution at the very twilight of his career, gaining the crucial Game Five victory in the 1933 Series with a brilliant four-inning relief stint against the then-powerful Washington Senators in the nation’s capital.

The third and final dimension of Luque’s lengthy career is the one almost totally unknown to North American fans: his brilliant three decades of seasons as both player and manager in the winter-league play of his Caribbean homeland. As a pitcher in Cuba, Luque was nearly legendary in stature, compiling a 93-62 (.600) career mark spread over 22 short seasons of wintertime play, yet ranking as the Cuban League’s leading pitcher (9-2) on only a single occasion, in 1928-29. In 1917 he was also the league’s leading hitter (.355), and he capped it all by managing league championship teams on eight different occasions (1919-20, 1924-25, 1934-35, 1939-40, 1941-42, 1942-43, 1945-46, and 1946-47).

Luque’s reputation in the wintertime Cuban League was arguably in the end most durable as a manager. This claim stands despite the fact that his pitching achievements were considerable, and also despite the fact that Luque was for most of his career a playing manager and not simply a bench-riding skipper. But as a field manager Luque has few rivals anywhere in Cuban League annals, as any mere statistical summary will attest. As a pitcher, by contrast, he was remarkable but hardly unique. His record does not match that of Martín Dihigo, who recorded 106 victories in 19 winters. Yet no one else pitched 22 winter seasons in Cuba, nor were there any other 93-game winners outside of Dihigo. (Cup-of-coffee big leaguer Adrian Zabala also compiled 90 victories over the course of 16 Cuban seasons.) But José Méndez, Adolfo Luján, and Bebé Royer did record higher lifetime winning percentages (as did of course Dihigo) and all logged more seasons as individual league leaders. Luque’s victory totals on the mound in Cuba are as much a testament to his longevity as to his year-in and year-out dominance.

But as a manager there is only the venerable Miguel Angel González to rival Luque for years of service and overall winning success. Luque was notably the only manager to log time with each of the “big four” teams in Cuba, serving the bulk of his career at the helm of Almendares (where he first managed in 1920), but also spending three seasons on the bench with Habana (1924, 1955, 1956) and one each with Cienfuegos and Marianao. His one bench assignment with Los Elefantes (1946) gained for Cienfuegos the club’s very first pennant in team annals.

Luque posted seven outright titles during his 19 years at the helm of Almendares (where he won 401 overall games), his career winning mark stood at 565 and 471 (.545), and he experienced only seven losing ledgers, five with Los Alacranes (the Almendares Scorpions). Luque’s 24 total winters as a Cuban League manager is outpaced only by Miguel Angel González with 38 (all served with Club Habana), and his 565 wins are also outdistanced only by the unapproachable 917 rung up by Miguel Angel. But while Luque was a regular winner with Almendares (finishing first or second in 14 of 19 years with the Blues), González – like the venerable Connie Mack – amassed his victory totals largely through relentless accumulation. Miguel Angel suffered a handful of the most embarrassing Cuban League seasons on record during his own marathon career (including an unimaginable 8-58 ledger in 1938) and yet still posted a career winning percentage of .538 (a fraction behind Luque). González’s record 13 league pennants surpass Luque’s total by a half-dozen but were earned over a career 37 percent longer. And Luque’s managerial record is also augmented by back-to-back Mexican League pennants earned with Nuevo Laredo in the early 1950s.

Perhaps Dolf Luque’s most significant contribution to the national pastime (both American and Cuban versions) was his proven talent for developing big-league potential in the players he coached and managed over several decades of winter-league play. One of Luque’s brightest and most accomplished students was future New York and Brooklyn star hurler Sal “The Barber” Maglie, who learned his brazen style of “shaving” hitters close to the chin from his tough Cuban mentor. Luque (who had developed his own “shaving” techniques with National League hitters two decades earlier) was Maglie’s pitching coach with the Giants during the latter’s rookie 1945 season, as well as his manager with Cienfuegos in the Cuban League that same winter, and at Puebla in the Mexican League in the winter seasons of 1946 and 1947. Maglie often later credited Luque above all others for preparing him for major-league success.3 And so did Latin America’s first big-league batting champion, Roberto “Beto” Avila, who also played for Luque in Puebla during the Mexican League campaigns of 1946 and 1947. Another of Luque’s disciples was future Washington and Minnesota ace Camilo Pascual, who first mastered a knee-buckling curveball when Luque coached him with the Cienfuegos Cuban winter-league club. It was this very talent for player development, in the end, that perhaps spoke most eloquently about the onesidedness of Luque’s widespread popular image as an emotional, quick-tempered, and untutored ballplayer during his own big-league playing days.

When it comes to selecting a descriptive term to summarize Luque’s career, “explosive” has often been the popular choice. For many commentators, this is the proper phrase to describe his reputedly excessive temperamental behavior, his exaggerated on-field outbursts, his infrequent yet widely reported pugilistic endeavors (Luque never shied away from knocking down his share of plate-hugging hitters, of course, but then neither did most successful moundsmen of his era). For still others, it characterizes a career that seemed to burst across the horizon with a single exceptional year, then fade into the obscurity of a forgotten journeyman big leaguer. But both notions are wide-of-the-mark distortions, and most especially the one that sees Luque as a momentary flash upon the baseball scene.

“Durable” would be the far more accurate epitaph. For Dolf Luque was a tireless warrior whose pitching career seemed to stretch on almost without end. His glorious 1923 season was achieved at the already considerable age of 33; he again led the National League in ERA (2.63) two summers later at age 35; he recorded 14 victories and a .636 winning percentage in 1930 while laboring for the Dodgers at the advanced age of 40; his two shutouts that season advanced his career total to 26, a mark unsurpassed among Latin pitchers until the arrival of Marichal, Pascual, Tiant, and Cuéllar in the decade of the ’60s. Referred to widely as the rejuvenated “Papá Montero” by 1933, he recorded eight crucial wins that summer and the clinching World Series victory at age 43. His big-league career did not end until he was 45 and had registered 20 full seasons, only one short of the National League longevity standard for hurlers held jointly by Warren Spahn and Eppa Rixey.

Luque’s special claim on durability and longevity is even further strengthened when one takes into consideration his remarkable winter-league career played out over an incredible 34 winters in Cuba. Debuting with Club Fe of Havana in 1912 at the age of 22, the indefatigable right-hander registered his final winter-season triumph at age 46 in 1936, then returned a full decade later to pitch several innings of stellar relief work in the 1945-1946 season at the unimaginable age of 55. Luque’s combined totals for major-league and winter-league baseball – stretching over almost 35 years – comprise 284 wins, a figure still unrivaled by any of his Latin countrymen save Tiant and Dennis Martínez. And for those critics who would hasten to remind us that longevity alone is not sufficient merit for baseball immortality, it should also be established that Luque’s 20-year ERA of 3.24 outstrips such notable enshrined or wannabe Hall of Famers as Bob Feller, Early Wynn, Robin Roberts, Nolan Ryan, and Lew Burdette, to name but a few of baseball’s most unforgettable mound stars.

Perhaps the greatest irony surrounding Dolf Luque’s big-league career in the end is the misconception that he was merely a cold, laconic, and hot-tempered man, either on the field or off. Upon the occasion of the Cuban hurler’s premature and largely unnoticed death at 66 (of a heart attack in Havana on July 3, 1957), legendary sportswriter Frank Graham provided the final word and perhaps the most eloquent tribute to this Pride of Havana who had reigned so stoically as the first certified Hispanic baseball star:

It’s hard to believe. Adolfo Luque was much too strong, too tough, too determined to die at this age of sixty-six. … He died of a heart attack. Did he? It sounds absurd. Luque’s heart failed him in the clutch? It never did before. How many close ballgames did he pitch? How many did he win … or lose? When he won, it was sometimes on his heart. When he lost, it was never because his heart missed a beat. Some enemy hitter got lucky or some idiot playing behind Luque fumbled a groundball or dropped a sinking liner or was out of position so that he did not make the catch that should have been so easy for him.4

Like many Cuban ballplayers of his era, Adolfo Luque emerged from working-class origins, having been born Adolfo Luque Domingo de Guzman in the low-rent district of Havana on August 4, 1890, and almost nothing is known of his modest childhood years. He joined the newly formed republican army sometime late in the 20th century’s first decade, serving as an artilleryman and also building a small local reputation as a hard-slugging third baseman on the infantry baseball club. Early military baseball experience ironically opened the door on an athletic career when the Vedado Tennis Club team – one of the best in the country’s thriving amateur league – recruited his services and promptly converted him (as the result of his obviously strong arm) to a pitching assignment. Within a matter of months Luque was signed on by the Fe ballclub of the professional league, where in 1912-1913 he lost all five decisions of his first two pro campaigns.

From his earliest days as a budding professional through his lengthy big-league and winter-league careers, the stocky 5-foot-7 rough-and-tumble ballplayer was best known for his surly personality and quick-fire temper, even among those loyal countrymen who saw him as national hero after his miraculous 1923 big-league season in Cincinnati. It was that rough-around-the-edges personality that earned him the Papá Montero nickname that became his popular handle on his native island. The odd moniker referred to a legendary Afro-Cuban rumba dancer celebrated in song and verse (especially in the popular rumba lyrics composed by Eliseo Grenet) as a high-living pimp and trickster. In the case of the white-skinned Luque, the implied reference was not a racial one but rather a suggestion of the ballplayer’s exceptional charisma, assumed sexual prowess, and overly aggressive on-field and off-field behavior.

Much of this off-color reputation was built around not only the Stengel incident, or Luque’s penchant for tossing close to batters’ heads, but also several widely told if perhaps apocryphal tales involving the use of firearms. Rumor had it that Luque often carried a gun, sometimes even while in uniform, and may well have used it to intimidate his wayward charges on more than one occasion while managing in the Cuban winter league. One account involved Negro league legends Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe and Rodolfo Fernández. Supposedly an enraged Luque – believing that his imported African American catcher had been dogging it on the field – attempted to fire off a round at Radcliffe in the Tropical Stadium locker room. The frightened Radcliffe was supposedly saved only when Fernández pushed away the manager’s arm as he attempted to gun down his goldbricking backstop. A second incident involved black pitcher Terris McDuffie (who pitched for Luque’s Marianao club in the early ’50s), a heavy drinker and womanizer cut in Luque’s own model. This account suggests that McDuffie once told Luque he had a hangover and thus was not up to starting a game, yet then quickly changed his mind once the short-tempered manager returned to the locker room from his adjacent office waving a loaded pistol.5

If some of the tales surrounding Luque’s outrageous public behavior might well be based more on fancy than fact, it is nonetheless common knowledge that he was indeed prone to expensive tastes and extravagant personal indulgences. He was a flagrant womanizer, a heavy drinker, a brash and often profane public figure, and a reckless gambler (with a passion for the brutal cockfights that were then still legal in Havana). He squandered most of his baseball earnings on his lavish lifestyle and thus died only one step ahead of the poorhouse.

Little more is known of the details of Luque’s adult family life away from the public spotlight than of his obscure Havana childhood. He was married to a Mexican woman, Yvonne Resek, a native of Puebla whom he met while managing in that city and who ultimately survived him. His then-still-living widow was the guest of honor at his 1985 posthumous induction into the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame. On that particular ceremonious occasion in Monterrey, Mrs. Luque uttered the provocative statement that she wasn’t in fact the pitcher’s widow since she didn’t believe that Luque was actually deceased. In support of her bizarre (perhaps tongue-in-cheek) claim, Resek cited an incident from the famed athlete’s earlier life when he seemed to reappear from the dead. The story was that Luque and some fellow ballplayers were once on a ship bound from Havana to Miami that was reportedly lost in the Bermuda Triangle. As the tale has it, a day of mourning was proclaimed in Havana to honor the lost athletes, but three days later the ship miraculously landed safely in Miami. That incident gave birth to yet another famed rumba tune entitled To Cry for Papá Montero. One other known detail of the pitcher’s life is that his only daughter, Olga Luque, was a talented swimmer who competed on several occasions (including the 1938 Central American Games) for the Cuban national aquatic team.

Luque was far more than the man who courted baseball legend by once belting the loud-mouthed Casey Stengel. It would surely be an exaggeration to argue for Luque’s enshrinement in Cooperstown solely on the basis of his substantial yet hardly unparalleled big-league numbers, though some have grabbed immortality with far less impressive credentials. It would be equally a failure of historical perspective to dismiss him as a journeyman pitcher of average talent and few remarkable achievements. Few other hurlers have enjoyed such dominance over a short span of a few seasons. Fewer still have proved as durable or maintained their dominance over big-league hitters at so hoary an age. Almost none have contributed to the national pastime (Cuba’s and North America’s) so richly after the door slammed shut upon an active big-league playing career. Almost no other major-league pitcher did so much with so little fanfare.

The case for depositing Cuba’s most renowned hurler of the post-Deadball Era in the hallowed halls of Cooperstown, like all those pleas for reassessment of ballplayers standing squarely on the cusp of greatness, may arguably reflect the narrow prejudices of the advocate as much as the considerable merits of the nominee. It could very well be countered that Luque, like Roger Maris or Brady Anderson, was largely a one-season aberration whose 1923 “year in the sun” far outstripped any of his other achievements. Or one might well take the position, as in the case of Brooklyn’s Gil Hodges, that the Cuban right-hander was not even the best player on his own team at the time of his loftiest triumphs. But the numbers amassed across the full decade of the ’20s – ten consecutive seasons of double-figure victory totals, three seasons pacing the senior circuit in shutouts, and a pair of ERA crowns – at least work in Luque’s case to neutralize if not silence such naysaying. And when it comes to recognizing trailblazing pioneers among Latin ballplayers on the big-league scene before Jackie Robinson, on that front alone Havana’s Dolf Luque remains lodged in a class entirely by himself.

This was a pitcher, let it never be forgotten, whose numbers for decades stood unmatched by any of his Hispanic countrymen, one who today still remarkably outstrips all Latino-bred pitchers with perhaps few exceptions of the immortal Marichal, the legendary Tiant, and the more contemporary Dennis Martínez, and possibly now the flamboyant Pedro Martínez. In the oftentimes falsely attributed phrase of the same Casey Stengel who was once an accidental recipient of one of Dolf Luque’s most torrid knockout pitches – “You can look it up!”6

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express his indebtedness to Andy Sturgill, whose peer review and numerous insightful suggestions served to strengthen this biography considerably.

Sources

Bjarkman, Peter C., A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007).

Figueredo, Jorge S., Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003).

González Echevarría, Roberto, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Kaese, Harold, The Boston Braves (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948).

Rathgeber, Bob. “A Latin Temper on the Mound – Adolfo Luque,” in Cincinnati Reds Scrapbook (Virginia Beach, Virginia: JCP Corporation of Virginia, 1982), 54-55.

Torres, Angel, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Montello, California: self-published), 1996.

Wheeler, Lonnie, and John Baskin, The Cincinnati Game (Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press, 1988).

Notes

1 Lonnie Wheeler and John Baskin, The Cincinnati Game.

2 Luque’s role with the 1914 and 1915 Braves was so insignificant that the Cuban benchwarmer receives no mention whatsoever in the pages devoted to those years by Harold Kaese in his classic 1948 Putnam Series history of the storied ballclub.

3 Maglie’s indebtedness to Luque’s coaching and its impact on his own eventual big-league successes during the 1950s is mentioned by both Roberto González Echevarría (The Pride of Havana, 145, 329) and by Maglie biographer Judith Testa (in her SABR Biography Project essay found on the SABR BioProject website).

4 Frank Graham, Adolfo Luque obituary, New York Journal American, July 4, 1957.

5 Both Luque gun-toting incidents – including Rodolfo Fernández’s eyewitness report of the Radcliffe saga – are detailed by Roberto González Echevarría (The Pride of Havana, 145).

6 A somewhat different version of this biography appeared as Chapter 2 (“Adolfo Luque – The Original ‘Pride of Havana’ ”) of my book A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006. An even earlier version was published as “First Hispanic Star? Dolf Luque, Of Course” in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal 19 (1990), 28-32.

Full Name

Adolfo Domingo de Guzman Luque

Born

August 4, 1890 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

July 3, 1957 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.