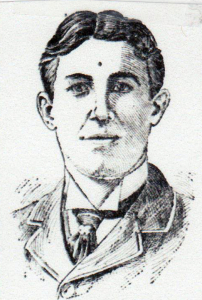

Huyler Westervelt

Beginning in 1888 and for the next five summers, right-hander Huyler Westervelt was a pitching standout on various amateur baseball teams in the greater New York City area. As a result, he attracted a number of offers from major league clubs but did not accept one until he signed with the New York Giants in January 1894. Used mainly as a spot starter during the season, Westervelt underperformed, posting a losing record for a pennant-contending Giants club. Nevertheless, New York wanted him back for 1895. But Westervelt refused to accept the salary cut imposed by incoming club boss Andrew Freedman and returned his contract unsigned. These events – the tendering of a low salary contract by Freedman and Westervelt’s rejection of same – then repeated themselves for the next six years.

Beginning in 1888 and for the next five summers, right-hander Huyler Westervelt was a pitching standout on various amateur baseball teams in the greater New York City area. As a result, he attracted a number of offers from major league clubs but did not accept one until he signed with the New York Giants in January 1894. Used mainly as a spot starter during the season, Westervelt underperformed, posting a losing record for a pennant-contending Giants club. Nevertheless, New York wanted him back for 1895. But Westervelt refused to accept the salary cut imposed by incoming club boss Andrew Freedman and returned his contract unsigned. These events – the tendering of a low salary contract by Freedman and Westervelt’s rejection of same – then repeated themselves for the next six years.

Westervelt’s refusal to submit torpedoed his professional career. The first time that the young hurler backhanded a proffered pact, the easily miffed and often vindictive Freedman suspended him. Subsequently, he kept Westervelt’s name on the New York Giants reserve list each year through the 1901 season, preventing any other major or minor league club from engaging him without Freedman’s permission – which the club boss steadfastly refused to give. As a consequence, Westervelt was reduced to pitching for semipro and amateur teams for the remainder of his playing days. Post-baseball, he made a tenuous living as a broker of speculative commodity stocks until his retirement to upstate New York in the mid-1930s. By the time of Westervelt’s death in October 1949, he was so far removed from the baseball scene that the game did not take note of his passing for another 50-plus years. The story of this neglected one-season New York Giant follows.

Huyler Westervelt was born on October 1, 1869, in Piermont, New York, a Rockland County village situated near the state’s southern border with New Jersey. He was the second of three children1 born to railroad clerk Peter Westervelt (1844-1929) and his wife Sarah (née Huyler, 1836-1883), both descended from Dutch Protestant colonists who arrived in New Amsterdam (soon to become New York City) in the early 1660s. When Huyler was still a boy, the family relocated to nearby Tenafly, New Jersey.2 There, he attended class through high school graduation.3

A somewhat fanciful profile published in the New York Clipper stated that Huyler Westervelt “learned to play ball” while in school, following the example of his father and an uncle, “both of them being very clever amateur players in their day.”4 By age 18, Huyler was pitching for the Englewood (New Jersey) Field Club, a crack North Jersey amateur club. Tall, slim, and handsome,5 Westervelt had “a good delivery, terrific speed, and sharp, deceptive curves.”6 He returned to the Englewood FC in 1889 and “his remarkable pitching gave that club a prominent place among the amateur clubs of the [New York City] vicinity.”7 But the season ended on a sour note, with Westervelt dropping a close decision in the area championship contest at the Polo Grounds to a club from Staten Island.8

In 1890, Westervelt joined the Bayonne-based New Jersey Athletic Club, the Garden State’s premier amateur nine. Also members of the NJAC team were the Currie brothers: catcher Walter, second baseman Joe, and pitcher Doc (William), Huyler’s future brothers-in-law. On May 30, Westervelt demonstrated his pitching prowess to his new teammates by throwing a no-hitter at the Elizabeth AC team.9 Late in the year, he “pitched the game of his life” but lost the second match of the Amateur Athletic Union Base Ball League championship series to the Detroit AC, 3-2.10 The following week, Westervelt threw a four-hitter at Detroit, only to have three unearned runs cost him another 3-2 defeat in the deciding game of the title showdown.11

Westervelt remained with the NJAC for the next three seasons, turning in top-notch pitching performances that included a one-hit, 1-0 whitewash of his former club, the Englewood FC, in August 1893.12 During this period, he received “innumerable offers to join [National] League clubs,”13 all of which he declined. Baseball commentators past and present have speculated that Westervelt’s reputed social status dissuaded him from turning professional,14 and that “it was only by much persuasion on the part of personal friends that he finally agreed to play professionally.”15 But such assertions confuse our subject, the son of a railroad clerk (later a hotel doorman), with distant-relation upper crust Westervelts.16 It was also alleged that Westervelt feared that major league “competition would be too fast” for him.17 Or that he saw “a vast deal more profit” in entering into the stockbrokerage business than in “taking the mercurial chances which always characterize a pitcher’s career.”18

Whatever its basis, Westervelt’s reticence did not discourage one suitor: New York Giants player-manager John Montgomery Ward. In need of arms to bolster his pitching staff, Ward bore down on Westervelt over the offseason and finally induced him to agree to join the Giants.19 Once the contract was signed, Ward declared, “I am delighted that Huyler Westervelt has been secured. I have been trying to get him for the Giants for the last two years, and he is not only a good pitcher, but he is a clever batsman and baserunner.”20

As it turned out, the real talent secured by the Giants over the winter was not Westervelt, but right-hander Jouett Meekin, obtained in a trade with the Washington Nationals. During the 1894 season, Meekin (33-9, .786) combined with reigning staff ace Amos Rusie (36-13, .735) to provide New York with the National League’s dominant pitching duo. But club skipper Ward gave Westervelt the opportunity to show his stuff, as well. The newcomer made his major league debut in Baltimore on April 21. Facing a lineup that featured no fewer than six future Hall of Famers (Dan Brouthers, Willie Keeler, John McGraw, Hughie Jennings, Joe Kelley, and Wilbert Robinson), Westervelt began auspiciously, holding the Orioles scoreless through the first five innings and taking a 3-1 lead into the bottom of the seventh. Then, a three-run Baltimore rally sent him to a 4-3 defeat. Despite that outcome, Westervelt’s press notices were favorable, with the New York Herald declaring that “Westervelt proved that the management made no mistake when it signed him.”21

Almost two weeks passed before he was given another start and suffered another late-inning setback. Holding a 3-1 lead going into the ninth against Philadelphia, Westervelt fell apart, surrendering six runs and costing the slow-starting (now 4-7) Giants another defeat. Still, much of the hometown press remained in the rookie hurler’s corner, with the New York Evening World observing that “it doesn’t serve any good purpose to throw rocks at Westervelt at this stage of the game. The boy has speed, plenty of it, and he is a puzzler who will fool the best of ’em.”22 Two days later, Westervelt vindicated the endorsement by posting his first big league victory: a complete-game, three-hit, 5-2 triumph over the defending National League champion Boston Beaneaters. After the game, the New York Times entered the ranks of his admirers, informing readers that “Westervelt is a first class man as a pitcher, game as the historical pebble, and will make his mark this year.”23

Westervelt seemingly solidified his place in the New York rotation by posting two quick follow-up victories. But thereafter, four straight setbacks gave manager Ward some pause. After a late-game rally saved Westervelt from yet another loss on June 7, almost three weeks passed before he received his next starting assignment. A five-hit, 11-0 shutout of the St. Louis Browns restored Westervelt to Ward’s good graces.24 It also coincided with the Giants’ upward surge in National League standings.

Regrettably, after Westervelt chipped in a 4-3 victory over Louisville in early July, he contributed little to the Giants’ cause. He dropped his next two decisions and then was hit hard in a mid-July no-decision against Washington. Thereafter, Ward began using right-hander Lester German in Westervelt’s rotation spot. A doubleheader against Brooklyn in early August supplied Westervelt with a reprieve, and he responded with a complete-game 17-3 victory. But days later, Westervelt was driven from the box early in a rematch against Brooklyn that ended in a lopsided 21-8 loss.

On August 11, 1894, the major league career of Huyler Westervelt ended the way it had begun – with an away game against the Baltimore Orioles. This time, however, he showed none of the promising form of his debut. Mercilessly left in to pitch the entire game by manager Ward, Westervelt was hammered for 25 base hits while giving up nine walks en route to absorbing a 20-1 shellacking.25 Although he remained on the roster for final six weeks of the season, Westervelt became the Giants’ forgotten man, never used in league competition again. Indeed, he no longer even accompanied the club on road trips. While the Giants tried to chase down Baltimore for the National League crown (but fell three games short),26 Westervelt was given leave to pitch semipro games in New Jersey.27

When the Giants traveled to Baltimore to begin the postseason Temple Cup showdown between the National League’s top two clubs, Westervelt was among the New York contingent making the trip. Rather than get out enemy batsmen, however, his job was to keep watch on Oriole Park turnstiles to ensure that the Giants were not shortchanged on gate receipts.28 New York proceeded to sweep the Cup in four games from the outcome-indifferent Orioles, but Westervelt’s share of the match proceeds, if any, is unknown.29

At season end, Westervelt’s numbers were not facially impressive. In 23 games, he went 7-10 (.412) for a New York club that otherwise posted an 81-34-7 (.771) record. The clobberings that he received in his final two outings inflated Westervelt’s ERA to 5.04 in 141 innings pitched, while his ratio of strikeouts (35) to walks (76) was also poor. Yet compared with National League-wide pitching stats for the offensively turbocharged 1894 season, Westervelt’s figures were tolerable. His ERA was actually slightly below the circuit norm (5.33), as was his .295 Opponents Batting Average, as NL batsmen posted a still-record .309 combined batting average that year, overall.

During the offseason, the New York Giants were in a state of flux, with law school graduate Ward leaving the game to prepare for the New York bar examination.30 Of more long-term consequence, millionaire Manhattan businessman Andrew Freedman acquired majority control of franchise stock and placed himself in charge of club affairs. The new club boss was exceptionally astute in matters of commerce; during his lifetime, Freedman amassed separate fortunes in real estate; municipal bonding, insurance, and finance; and subway construction, and he was easily the wealthiest National League club owner.31 But Freedman knew little about baseball and his condescending, often combative, personality quickly alienated fellow club owners, Giants players, the sports press, and the Polo Grounds faithful, alike. Only once during his administration did New York even figure in the NL pennant chase – and that was the season (1897) that club president Freedman spent most of the summer in Europe. In the end, Freedman’s eight-year (1895-1902) tenure at the helm of the franchise was grim, the darkest period in New York Giants history.32

Although Westervelt had proved a disappointment in 1894, pitching remained at a premium in the National League. And Westervelt was still young (25) and likely to improve now that he had gained some professional experience. New Giants manager George Davis therefore planned to try him out again in spring camp. But the contract tendered to Westervelt by Freedman included a pay cut from his previous season’s $1,800 salary. The pitcher refused to accept the reduction and promptly returned the contract unsigned.33 Unaccustomed to and affronted by opposition from an underling, Freedman reacted harshly, suspending the young hurler indefinitely. With his professional career now in limbo and in need of a job, Westervelt accepted a position as assistant manager for the sporting goods store that the Overman Wheel Company was opening in Manhattan.34 And on weekends, Westervelt agreed to pitch for the “amateur” Orange Athletic Club in nearby northern New Jersey.35

By June, the landscape had changed dramatically. The Giants had gotten off to another slow start, with staff aces Rusie and Meekin nursing arm problems.36 As a result, the club quietly approached Westervelt about returning to the fold. Realizing that he now held the upper hand in the negotiations, Westervelt demanded an increase on his previous season’s wage. This time, it was Freedman who refused to submit.37 The impasse left the Giants in continued free fall in National League standings (the club eventually finished the season in ninth place) while Westervelt resumed weekend pitching for the Orange AC. Freedman, however, exacted his revenge as the campaign wore on, refusing to grant Westervelt’s release when Baltimore Orioles manager Ned Hanlon wanted to sign him.38 And even though Westervelt had not thrown a pitch for New York during the 1895 season, Freedman renewed the club’s reserve list hold on him that autumn, precluding other clubs in Organized Baseball from engaging the pitcher for 1896.39

That winter, Westervelt became a local hero, plunging into icy lake water on Staten Island to rescue a drowning teenage skater who had fallen through thin ice.40 He also changed jobs, joining the baseball department of a sporting goods store opened in lower Manhattan by the A.G. Spalding Company.41 Yet Westervelt had not given up hope of resuming his professional playing career. As the previous season, he returned the contract tendered to him by the Giants unsigned.42 He then instituted proceedings before the National League Board of Arbitration to undo the club’s reserve clause hold on him. The gravamen of the Westervelt petition was the claim that he had never signed an official NL contract. Rather, back in January 1894 he had merely signed a document prepared by [then] Giants honcho Edward Baker Talcott that did no more than memorialize his agreement to play for the New York club that season. Neither that instrument nor any other executed by Westervelt contained a reserve clause.43

For reasons unknown, Westervelt abandoned his case before the board passed judgment on it, announcing instead his intention to retire from professional baseball.44 That declaration notwithstanding, shortly thereafter he proposed to make himself available to the pitching-strapped Giants – staff ace Amos Rusie was idled by a contract squabble with Freedman that ultimately saw him sit out the entire 1896 season – via a singular arrangement whereby Westervelt would pitch selected games for the New York club “if his employers [the A.G. Spalding Company] gave their permission.”45 This impractical proposition was never taken up by the Giants, and Westervelt returned to pitching for the Orange AC that summer. One such outing saw him lose an in-season exhibition game to the Giants, 13-6.46 At season’s end, Freedman exercised his now-ritual prerogative to place Westervelt on the New York reserve list for 1897.47 His tribulations with the mean-spirited Giants owner, however, did not prevent Westervelt from ending the season on a high note. In early October, he took Gertrude Currie, the younger sister of former NJAC teammates, as his bride.48 Their union endured for the next 53 years and yielded daughter Madelon in 1900.

The next several years followed a familiar pattern. Freedman annually tendered a low salary contract to Westervelt which the pitcher then predictably returned unsigned.49 Unavailable to other professional ball clubs – another attempt by manager Hanlon to secure Westervelt for Baltimore was stymied by the Giants club boss that season50 – he retained his weekday job at the Spalding sporting goods store and pitched on weekends for various local amateur and semipro clubs. One such nine was sponsored by the New York Elks Club and included former Giants manager John Montgomery Ward and ballplayer-turned-sportswriter Sam Crane.51 But regardless of how Westervelt spent his summers, each fall Andrew Freedman put his name on the New York Giants reserve list for the ensuing campaign.52 But even the Giants roster was off-limits to Westervelt. When Cap Anson became the club pilot in early 1898, he contacted Westervelt to inform him that he [Anson] was in control of personnel decisions for the coming season and that he wanted the pitcher for the New York team. “That may be,” replied Huyler, “but Freedman won’t allow me inside of his grounds.”53

Nearing age 30, Westervelt was released by the Orange AC in July 1899.54 Weeks later, pitching for a semipro team from nearby Hoboken, he was pummeled by a Cuban nine, losing 26-8. That performance led a local newspaper to observe that “probably in all Westervelt’s career he has not been so badly and frequently hit.”55 Thereafter, he pitched only the odd game for area amateur clubs. Nevertheless, that October Andrew Freedman again placed him on the Giants reserve list, prompting Sporting Life to observe that Westervelt’s reservation was “one of the standing jokes of each season … The constant appearance of his name on the list is a farce comedy.”56

Westervelt had previously dabbled in trading stocks during the offseasons of his playing days. He now made it his fulltime profession, taking a seat on the Consolidated Exchange, a competitor of the New York Stock Exchange that concentrated on the trade of mining stocks and other risky securities.57 In short order, Westervelt got himself suspended from the exchange, being “unable to meet his obligations, and forced to make an assignment” of certain stocks that he held.58 Within 24 hours, however, the novice trader covered his shortfalls and was restored to good standing.59 But in future, the speculative, frenetic nature of the action on the Consolidated Exchange would cause Westervelt additional embarrassments. Meanwhile, Giants boss Freedman reserved the now retired pitcher for the 1901 season.60

In late December 1901, Westervelt was again suspended from the Consolidated Exchange, unable to meet the margin call on sugar stocks.61 As before, he was soon restored to good standing but thereafter abandoned the exchange, working instead as a broker for established firms, including the one run by his Currie brothers-in-law.62 Meanwhile, the September 1902 sale of Andrew Freedman’s majority interest in the New York Giants to John T. Brush ended the practice of the club annually placing Westervelt on its reserve list. But by this time his ballplaying was confined to an occasional Elks game and the like. The last discovered press mention of such a contest dates to May 1903, when Westervelt pitched a team of married stockbrokers to a 20-5 victory over their bachelor counterparts.63

Once he left the game, Westervelt receded into the shadows, his name appearing in newsprint only in random baseball nostalgia pieces,64 coverage of old-timers games,65 and the social page.66 The last known published photo of him depicts a well-dressed Westervelt talking baseball with retired heavyweight boxing champion Gene Tunney at a Manhattan sports luncheon in April 1938.67 By then, Westervelt was living in retirement in Pelham Manor, New York. He died at home there on October 14, 1949. Huyler Westervelt was 80, and survived by wife Gertrude, daughter Madelon Todd, and a grandson. Following funeral services, his remains were interred at Hudson City Cemetery, Hudson, New York.

The brief obituaries published for Westervelt did not mention his connection to baseball,68 and his passing went unnoted by the game for decades. No death information for Westervelt was published in baseball reference works from the 1951 first edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia by Turkin & Thompson to the release of the seventh edition of Total Baseball in 2001. Finally, these data were unearthed by SABR genealogical sleuths. The date and place of Westervelt’s demise were uncovered by Biographical Research Committee stalwart Richard Malatzky in 2003.69 Nine years later, 19th Century Committee member Dixie Tourangeau located the place of Westervelt’s interment.70 The first detailed account of the life that preceded those events appears here.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Photo credit: Huyler Westervelt, courtesy of Bill Lamb.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info provided above include the Huyler Westervelt file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Westervelt profiles published in “A Star of the First Magnitude,” Baseball History Daily, posted November 8, 2012; Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 2, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), and the New York Clipper, June 16, 1894; US and New York State Census data and other governmental records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 The other Westervelt children were James (1867-1948) and Evelyn (1872-1923).

2 At the time that this profile was being written, certain modern baseball reference works erroneously cited Tenafly as the birthplace of Huyler Westervelt. Government records including US and New York State censuses, however, establish that Huyler was born in Piermont, New York (where he is located on the 1870 US and 1875 NY State censuses) and did not arrive in Tenafly until the Westervelt family moved there sometime between 1875 and 1880.

3 Per the 1940 US Census. During his lifetime, it was occasionally asserted that Huyler Westervelt was a son of privilege and a college graduate. See e.g., O.P. Caylor, “The League Pitchers,” Jackson (Michigan) Citizen, May 29, 1894: 11, and “Baseball Boom Is Surely On,” New York Herald, May 6, 1894: 11. Neither was true.

4 “Huyler Westervelt,” New York Clipper, June 16, 1894: 233. Nineteenth century baseball scholar David Nemec relates that father Peter Westervelt pitched for a Jersey City amateur club in the 1870s. See Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 2, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 384.

5 From sources unknown, modern baseball reference works list Westervelt as 5-feet-9, 170 pounds. But a contemporary news story described Westervelt as “five feet ten inches tall, and he weighs 158 pounds.” See “Base Ball: Westervelt for New York,” Cleveland Leader, January 5, 1894: 3. And an Englewood FC team photo depicts young Westervelt as easily the tallest of the club’s 11 players and lightly framed. See Thom Karnik, “A Star of the First Magnitude,” Baseball History Daily, posted November 8, 2012. As for his appearance, Westervelt was later deemed “the best-dressed, best-looking pitcher in the National League,” in “Caught on the Fly,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, April 14, 1894: 13.

6 Per “Westervelt Signs with New York,” (Brooklyn) Standard Union, January 5, 1894: 8.

7 “Huyler Westervelt,” above.

8 As recalled decades later by local sportswriter William A. Caldwell in “At Random in Sportdom,” (Hackensack, New Jersey) Record, August 9, 1927: 12.

9 Per “Huyler Westervelt,” above.

10 “The Second Game: Echoes,” Bayonne (New Jersey) Herald, October 4, 1890: 3.

11 See “Crushed Again,” Bayonne Herald, October 11, 1890: 1.

12 See “Englewoods Euchered,” Bayonne (New Jersey) Times, August 3, 1893: 4.

13 “Base Ball: Westervelt for New York,” above.

14 See e.g., “A Star of the First Magnitude,” above.

15 See again, O.P. Caylor, “The League Pitchers,” above.

16 One such distant relative was Jacob Westervelt, a wealthy Tenafly-born shipbuilder who was elected mayor of New York City in 1853.

17 Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 384.

18 “Sporting News and Notes,” New York Evening World, May 26, 1893: 6.

19 As reported in “General Sporting Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 6, 1894: 5; “New Yorks Get Pitcher Westervelt,” Boston Globe, January 5, 1894: 1; and elsewhere.

20 “On the Diamond: John M. Ward Says New York Has a Good Chance for the Pennant,” Buffalo Enquirer, January 29, 1894: 8.

21 “Giants Lose the Third Straight,” New York Herald, April 22, 1894: 11.

22 “Was Westervelt Rattled?” New York Evening World, May 4, 1894: 5.

23 “Giants Beat the Champions,” New York Times, May 6, 1894: 7.

24 See “The Browns Shut Out,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 28, 1894: 5: “Westervelt occupied the box for the visitors and used a wonderful assortment of curves and good judgment. It was wholly through his exhibition that the home team were let down without a run.”

25 The hometown press reported that Baltimore manager Ned “Hanlon’s henchmen batted Huyler Westervelt’s old Dutch curves with ridiculous ease.” See “A Twenty to One Shot,” Baltimore Sun, August 13, 1894: 6.

26 Baltimore finished the 1894 season at 89-39-1 (.695). Three games behind in final NL standings were the New York Giants (88-44-7, .667).

27 See e.g., “Notes About Town,” Montclair (New Jersey) Times, September 22, 1894: 3, advertising Westervelt’s appearance for the Orange Athletic Club in an upcoming game against a club from Philadelphia.

28 Per “Orioles in a Huff,” New York Evening World, October 5, 1894: 8.

29 Unbeknownst to the public, New York and Baltimore players had privately agreed beforehand to an even split of their Temple Cup stipends regardless of which team won. Whether a non-participant like Westervelt received a cut is unknown.

30 The erudite John Montgomery Ward graduated from the law school at Columbia College [now University] in 1885 but deferred seeking admission to the bar until after his retirement from baseball.

31 David Quentin Voigt, The League That Failed (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1998), 220. Blanche McGraw stated that Freedman had as much money as the other National League club owners combined. Mrs. John McGraw, The Real McGraw (New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1953), 177.

32 The writer’s assessment of the Giants club boss is provided in his BioProject profile and “Andrew Freedman: A Different Take on Turn-of-the-Century Baseball’s Most Hated Owner,” The Inside Game, Vol. XIV, No. 3, June 2014, 13-18.

33 As reported in “Baseball in the Metropolis,” Sporting Life, March 9, 1895: 5; “General Sporting Notes,” Providence Journal, March 6, 1895: 2; and elsewhere. Westervelt’s 1894 salary was revealed two years later during litigation instituted against the New York club. See “Westervelt’s Appeal,” New York Sun, March 15, 1896: 9.

34 Per “Cycle Notes,” Indianapolis News, April 6, 1895: 12; “Among the Wheelman,” New York Times, March 19, 1895: 6.

35 Per “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 14, 1895: 8; “General Sporting Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 12, 1895: 3; and elsewhere. It was subsequently reported that Westervelt collected an under-the-table $135/month from the Orange AC. See Wm. F.H. Koelsch, “New York Is Sad,” Sporting Life, June 8, 1895: 3.

36 Arm problems reduced the combined log of Rusie and Meekin (69-22, .758 in 1894) to 39-34 (.542) in 1895.

37 As reported in “Diamond Flashes,” Baltimore Sun, June 21, 1895: 6; “Gossip from Field and Diamond,” Passaic (New Jersey) Daily News, June 18, 1895: 5; and elsewhere.

38 See “Personal,” Sporting Life, August 3, 1895: 2.

39 The New York Giants reserving of Westervelt for the 1896 season was reported in “Players Reserved for Next Year by Various Clubs,” Sporting Life, October 12, 1895: 3; “Here Is the List,” St. Paul Globe, October 10, 1895: 7; “League Reserve List,” New York Times, October 9, 1895: 6; and elsewhere.

40 As reported in “Huyler Westervelt’s Heroic Act,” Sporting Life, January 11, 1896: 4, and “Huyler Westervelt a Hero,” New York Journal, January 9, 1896: 11.

41 Per “Sporting News in Brief,” New York Times, March 7, 1896: 6.

42 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, January 18, 1896: 5.

43 “Westervelt’s Appeal,” above. On paper, the club president of the New York Giants was Cornelius Van Cott. In reality, vice-president Talcott ran the franchise.

44 As reported in “General Sporting Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 4, 1896: 8; “Passed Balls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 3, 1896: 5; and elsewhere.

45 Per “Nine Runs in One Inning,” New York Tribune, April 23, 1896: 14.

46 See “Giants Routed Orange Amateurs,” New York World, June 23, 1896: 11.

47 As reported in “Baseball: The Reserve List,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 3, 1896: 4; “The League Reserve List,” Pittsburg Post, October 3, 1896: 6; and elsewhere.

48 “Westervelt a Benedict,” New York Journal, October 8, 1896: 13; “Huyler Westervelt Married,” Trenton Evening Times, October 8, 1896: 4.

49 In 1897, Westervelt was offered $1,200 for the season. The next year, Freedman lowered the pitcher’s proposed season salary to $800. See “The League Meet,” Sporting Life, March 11, 1899: 4; “Pitched First Curve,” Washington (DC) Post, March 6, 1899: 8.

50 Per “Passed Balls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 16, 1897: 4; Wm. F.H. Koelsch, “New York Nuggets,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1897: 8.

51 See “Brooklyn Lodge Men Win,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 22, 1897: 4; “Elks and Actors to Play Ball for the Evening Journal Sunshine Fund,” New York Evening Journal, July 26, 1897: 6; “Elks Team to Make a Tour,” Indianapolis Journal, July 21, 1897: 3.

52 See “Official News,” Sporting Life, October 14, 1899: 8; “The League List,” Sporting Life, October 8, 1898: 1; “League Reserve List,” Sporting Life, October 9, 1897: 3.

53 “Anson and Freedman,” Illustrated Buffalo Express, July 10, 1898: 18.

54 Per “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, July 29, 1899: 5.

55 “Sports and Sportsmen,” Jersey City News, August 7, 1899: 4. The game’s box score credits the winning All Cubans with 27 base hits off Westervelt.

56 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, October 21, 1899: 5.

57 As noted in Wm. F.H. Koelsch, “New York News,” Sporting Life, February 10, 1900: 7.

58 Per “Sugar War Likely to Be Ended Soon,” New York Journal, March 24, 1900: 12; “Huyler Westervelt Assigns,” New York Tribune, March 22, 1900: 3.

59 “Huyler Westervelt Solvent,” New York Times, March 24, 1900: 12; “Westervelt Pays Up,” New York Evening Journal, March 23, 1900: 2.

60 Per “Reserve List,” Buffalo Evening News, October 9, 1900: 8; “The Reserve List,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 9, 1900: 6.

61 As reported in “Sugar Breaks Westervelt, (Hackensack, New Jersey) Evening Record, December 28, 1901: 1; “Broker Huyler Westervelt Embarrassed,” New York Times, December 28, 1901: 14; and elsewhere.

62 See “Currie Is One Broker Crazy over Base Ball,” (Tucson) Arizona Daily Star, September 26, 1908: 6; “Odds Offered on M’Clellan,” New York Sun, October 30, 1903: 2.

63 See “Wall-St. Brokers Curb Play Ball,” New York Tribune, May 24, 1903: 9. The Baseball-Reference entry for Huyler Westervelt has him playing for several low minor league clubs in 1905, but this is mistaken. The player in question there was James Westervelt, the captain-elect of the Williams College baseball team. See “Williams Captain,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, June 30, 1905: 3; “Westervelt Goes with Bradford?” (Corning, New York) Leader, June 14, 1905: 2. Huyler Westervelt never played a minor league game.

64 See e.g., James M. Smith, “Bergen County Reminiscences,” Record, April 26, 1930: 8; “At Random in Sportdom,” above.

65 Jack Farrell, “Old Stars at Jubilee Games Spoof Players of Today,” New York Daily News, May 15, 1925: 34.

66 “Tenafly,” Record, May 11, 1938: 8; “Miss Westervelt Weds,” Brooklyn Daily Times, October 3, 1921: 4.

67 “A Shakespeare Expert Learns about Baseball,” (Mount Vernon, New York) Daily Argus, April 26, 1938: 2.

68 See e.g., “Huyler Westervelt,” (New Rochelle, New York) Star-Standard, October 14, 1949: 2; “Huyler Westervelt,” Daily Argus, October 14, 1949: 2.

69 See “Better Name, Just as Tough,” Biographical Research Committee Report, January/February 2003, 1.

70 As reflected in an August 2012 memo contained in the Westervelt file at the Giamatti Research Center.

Full Name

Huyler Westervelt

Born

October 1, 1869 at Piermont, NY (USA)

Died

October 14, 1949 at Pelham Manor, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.