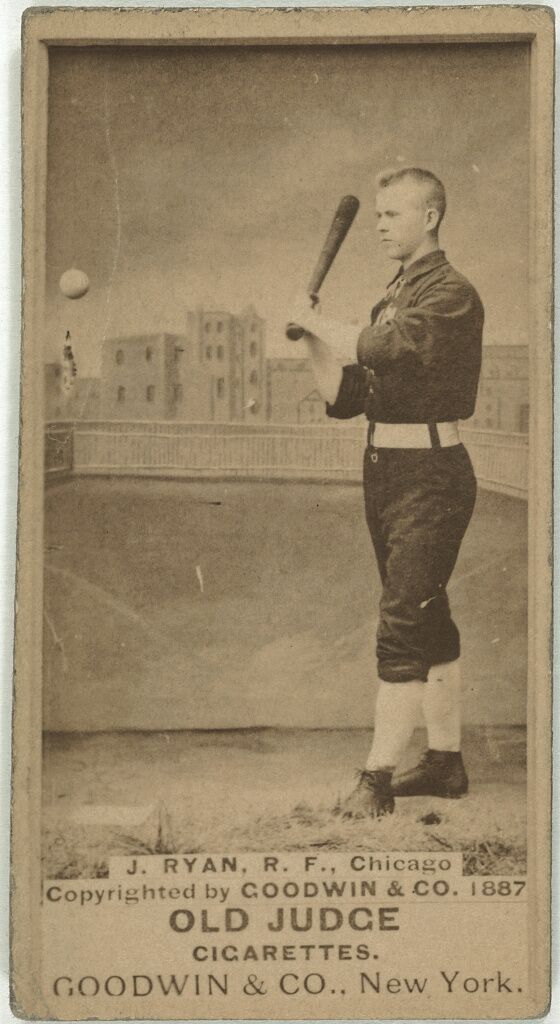

Jack Ryan

Of all the factors that influenced the development of baseball in its infancy, perhaps the most overlooked is the Great Irish Potato Famine. The famine compelled hundreds of thousands of Irish to immigrate to the United States in the middle of the nineteenth century, including the parents of future Hall of Famers John McGraw, Mike “King” Kelly, Joe Kelley, and Roger Bresnahan. The Ryan family came from Counties Kilkenny, Kildare, and Tipperary in “the Motherland,” first to St. John’s, Canada, and then to Haverhill, Massachusetts. It was there that John Bernard Ryan was born on November 12, 1868.

Of all the factors that influenced the development of baseball in its infancy, perhaps the most overlooked is the Great Irish Potato Famine. The famine compelled hundreds of thousands of Irish to immigrate to the United States in the middle of the nineteenth century, including the parents of future Hall of Famers John McGraw, Mike “King” Kelly, Joe Kelley, and Roger Bresnahan. The Ryan family came from Counties Kilkenny, Kildare, and Tipperary in “the Motherland,” first to St. John’s, Canada, and then to Haverhill, Massachusetts. It was there that John Bernard Ryan was born on November 12, 1868.

Jack Ryan began playing ball “at an early age” and made his professional debut at 18 with Belfast, helping the team finish first in the Maine State League in 1887. In 1888 Ryan was the everyday catcher for the Dovers of the New Hampshire/Massachusetts League, and won another championship. For the 1889 season he was picked up by Auburn, which proved to be the best club in the New York State League that year. So in his first three seasons, Ryan was a part of three championship teams, although he wasn’t around to see Auburn win the title. Late in that season he was picked up by the Louisville Colonels of the American Association, the worst team in the major leagues, who were on their way to an abysmal 27-111 record. But the following year, sure enough, the Colonels won the 1890 pennant. Their seven-game Championship Series against the NL champion Brooklyn Bridegrooms resulted in a deadlock – three wins apiece and one tie that was never completed. Ryan stayed with Louisville through 1891, during which “his accurate throwing arm was his chief point of excellence.”1 But perhaps because he had batted just .215 over his first 189 big-league games, Ryan was sold back down to Providence of the Eastern League for the 1892 season, and of course they became the league champion.

After Ryan hit.329 for Springfield in 1893, a tragic accident paved the way for Ryan to return to the majors. Boston Beaneaters catcher Charles Bennett slipped under a train that offseason and lost both of his legs. Backing up Charlie Ganzel, the 25-year-old Ryan played in 53 official games for Frank Selee’s Beaneaters in 1894 and batted .269. “He had the confidence of his pitchers,” wrote the New York Clipper, “and was a hard working, faithful player.”2 Selee brought Ryan back again in 1895 as Ganzel’s backup, and gave him a chance to win the starting job in ’96, but Ryan began the year in a 3-for-32 slump and soon found himself with the Syracuse Stars of the Eastern League. It was as a member of the Stars that Ryan made make his greatest contribution to the Beaneaters.

The Syracuse pitching staff included an inexperienced and unremarkable right-hander named Vic Willis. Ryan worked closely with Willis, and even built a freestanding wooden target to help the young pitcher develop his control.3 After two years under Ryan’s tutelage, Willis was one of the most dominant pitchers in the Eastern League (and helped Ryan win another championship). Primarily due to Ryan’s repeated recommendations, the Beaneaters purchased Willis for the 1898 campaign, and so began his Hall of Fame career.

Ryan also caught the attention of a big-league club himself that offseason – the Bridegrooms, who drafted him out of the Eastern League. But Ryan once again found major-league pitchers much tougher than the bush leaguers, finished with a woeful .189 batting average, and was back in the minors in 1899 playing for the Detroit Tigers in Ban Johnson’s Western League. The league itself was renamed the American League in 1900 but remained a minor league for one more season, during which Ryan filled a tremendous hole for the Tigers by playing 91 games at second base.

Ryan re-established himself in the majors with the St. Louis Cardinals from 1901 to 1903. But he batted only .203 in 226 games, and in 1904 was back in the minors with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. He had a solid season for the Blues, and another for Columbus in 1905, but at age 37 drew little interest from the big-league clubs. Always one to take the initiative, Ryan composed a letter in February of 1906 to August Herrmann, owner/president of the Cincinnati Reds and one of the most powerful men in Organized Baseball, to inquire, “How is your club for catchers? I am trying to get some club to make a trade for me, and I wish to get with a club that comes east, as I am a man with three children and in playing with an American Association club I don’t see them for six months. … Of course I have the name of an old-timer but I can assure you I will be in the game a great many more years, as I have always taken the best of care of myself and have never known the taste of any kind of liquor.”4

Herrmann was not interested, however, and Ryan had no choice but to return to Columbus for the 1906 season, without his family. At least he was able to find employment back in the Eastern League for 1907, playing 2½ years for Buffalo before the Bisons sold him to the Jersey City Skeeters on July 4, 1909.5 Jack Ryan was 40 years old that summer, and immediately upon acquiring him the Skeeters named him their manager, replacing 29-year-old first baseman Red Calhoun. Though he would continue as a part-time catcher through 1910, this transaction represented the beginning of Jack Ryan’s second career in baseball – as a manager.

In January of 1911, Skeeters owner Bob Davis died, leaving the franchise in a state of uncertainty. Local lawyer James Lillis quickly began assembling a syndicate to purchase the ballclub and keep it in Jersey City. Lillis assured fans that he would be willing to spend money liberally to put a winning team on the field.6 To prove it, he offered Ryan a three-year contract and full charge of the baseball operations, essentially making him both manager and general manager of the Skeeters.

Once again Ryan penned a letter to August Herrmann in Cincinnati, offering him a chance to join Lillis’s group. Once again he failed to convince Herrmann, but with a dialogue now opened between the two men, they decided to make a trade. Ryan packaged his starting shortstop from 1910, promising 21-year-old Jimmy Esmond, to Cincinnati in exchange for light-hitting infielder Tommy McMillan. An injury to McMillan caused Ryan to regret the deal almost immediately, and on March 11 he penned another letter to Herrmann in Cincinnati to complain that “I am getting roasted for the way the deal for McMillan turned. … Now if there is any way to let me have Downey,] see that I get him for that will be the only way I can square myself here.”7

Of course Herrmann wasn’t about to simply give away the Reds’ starting shortstop, so the issue dragged on, unresolved, into the summer. On June 28 Ryan wrote again, “As we have had to go to a big expense to get a short stop to take the place of McMillan I think that there is a little due to me. … Now I need a pitcher and if you are not going to use Jack Doscher is there any way you can let me have him? … I was not treated right in the McMillan matter and if you can do this for me I will deem it a great favor.”8 Even though Herrmann relented and sent his seldom-used left-hander Doscher to Jersey City as requested, the episode is indicative of the frustrations Ryan was feeling as the 1911 season dragged on.

In spite of his preseason promises, Lillis was either unwilling or unable to provide enough cash to keep the Skeeters competitive. During a home game at West Side Park one hot July afternoon, umpire Jack Doyle made a close call on a play at the plate, and ruled in favor of the visitors. An argument ensued, during which one of the Skeeters deliberately spiked Doyle, opening up a bloody gash on the top of his foot. No one in attendance was entirely sure which Skeeter had done it. Even Doyle was uncertain, amid all the chaos. League President Ed Barrow levied a $25 fine on Skeeters catcher Tony Tonneman, but Lillis was insistent that his manager had actually been the assailant. “I have a dozen witnesses, including a prosecuting attorney, who saw Ryan commit this unwarranted assault,” Lillis claimed. “I paid Tonneman’s fine because I knew he was innocent. I have an affidavit from Tonneman to the effect that Ryan told him to keep his mouth shut.”9

Whether Lillis really had such evidence, or whether he was just looking for a reason to get rid of Ryan, remains unclear. In either case, Lillis fired Ryan at the conclusion of the season, more than a month after the Doyle incident, and with two years remaining on his contract at $3,000 per year. Ryan announced that he would carry his case through the various baseball courts to the National Commission if necessary, and if that failed he would sue the club for damages and breach of contract. The dispute made headlines nationwide that winter, until the parties eventually settled in December for $3,500. “I have done what I could to drive Ryan out of the Eastern League,” said Lillis.10

Just when he thought he had finally attained some semblance of stability for his family, Ryan was suddenly without a job for 1912. Still bitter about the Jersey City situation, he dreamed of a job from which he couldn’t be fired. On February 24, 1912, Sporting Life reported that “since his exoneration of all charges at the last meeting of the league he has had several offers to take charge of minor league teams. He is endeavoring to secure a team of his own and may blossom out as a magnate before long.”11

Instead Ryan accepted an invitation from Washington Senators manager Clark Griffith to return to the big leagues as a coach. He spent two years with the Senators, a competitive and colorful squad featuring baseball clowns Germany Schaefer and Nick Altrock, as well as legendary hurler Walter Johnson. The highlight of his tenure occurred in the final game of each season, when Griffith allowed his coaches to play a few innings. On October 4, 1913, at Griffith Stadium, Griffith himself took the mound to pitch the eighth inning, with Ryan behind the plate in a farce of a game in which the umpires allowed each team four outs in one inning.12 Though no one took it seriously, the game was nonetheless official. Thus Ryan became the second player in major-league history (as of 2017 he’s still one of only 29) to appear in a game in four different decades, and along with Griffith etched his name into the record books as part of baseball’s oldest pitcher-catcher battery (with a combined age of 88 years).

A few months later, Ryan accepted the coaching job at the University of Virginia, one of the premier collegiate baseball programs in the nation, and held that post through 1916, then again in 1922. Through his friendship with Griffith, Ryan was able to schedule one or two exhibition games each spring against the Senators. After the collegiate season ended, Ryan managed to land gigs as an umpire in both the Central League (Class B) and Western League (Class A), beginning in 1916.

In the summer of 1922 Ryan got back into the dugout as manager of the Crisfield Crabbers in the Class-D Eastern Shore League in Maryland. In February 1923, incoming Red Sox manager Frank Chance hired Ryan as his pitching coach.13 Ryan spent five years with the Red Sox before finishing his career in the Class-B New England League, first as the skipper of his hometown Haverhill Hillies in 1928 and then, finally, with the New Bedford Millmen in 1929. “Everyone in the league held him in tremendous respect,” recalled former first baseman Jack Burns.14

After hanging up his spikes for good, Ryan continued umpiring amateur and semipro games in the Boston area. He also managed a bowling alley in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston until he had to be hospitalized with tuberculosis at age 83. He spent the last nine months of his life in the Boston Sanatorium until his death on August 21, 1952. He was survived by his wife, Marla, his daughters, Rita and Martha, his son, Jack, and also by his cousin’s grandson, Mike Ryan, who enjoyed a long career in major-league baseball as a catcher and coach for the Red Sox and Phillies from 1964 to 1995. But Mike said he had no memory of ever meeting Jack.15

Jack Ryan spent more than 40 years in the world of professional baseball, in various capacities. He debuted when catching equipment was primitive, when the pitcher stood just 50 feet from home plate, and before fouls were counted as strikes, yet he was still in uniform to see Babe Ruth swat home runs in Yankee Stadium. He is buried in St. James Cemetery in Haverhill.

Last revised: July 12, 2021 (zp)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied primarily on clippings from Ryan’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Unknown newspaper article dated November 11, 1890, in Ryan’s player file at the Hall of Fame.

2 New York Clipper, March 12, 1898: 27.

3 David L. Fleitz, Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 210-211.

4 Jack Ryan, letter to August Herrmann, February 20, 1906, from Ryan’s Hall of Fame player file.

5 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Ryan’s player file at the Hall of Fame.

6 Sporting Life, February 18, 1911: 9.

7 Jack Ryan, letter to August Herrmann, March 11, 1911.

8 Jack Ryan, letter to August Herrmann, June 28, 1911.

9 Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, December 12, 1911: 21.

10 Ibid.

11 Sporting Life, February 24, 1912: 3.

12 Bruce Nash and Allan Zullo. Baseball Hall of Shame (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989), 101.

13 James C. O’Leary, “Frazee Trades Russell and Reel to Senators for Catcher, Outfielder and All Around Player,” Boston Globe, February 11, 1923: 14. See also “Claim Jack Ryan Will Act as Red Sox Battery Coach,” Boston Herald, February 11, 1923: 19.

14 Roger Birtwell, “Hub’s Ryan Extends Proud Mitt Legacy,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1965: 9.

15 Ibid.

Full Name

John Bernard Ryan

Born

November 12, 1868 at Haverhill, MA (USA)

Died

August 21, 1952 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.