Jack Sheridan

“There never was a better umpire in the history of the game than Jack Sheridan.”1 — Nap Lajoie

Hall of Fame umpires Bill Klem and Billy Evans concurred: Jack Sheridan was the greatest umpire who ever lived.2 Sheridan worked in major and minor leagues from 1885 to 1914. He was a fearless arbiter in a raucous era and an innovator of umpiring technique. “A ballplayer is merely a ballplayer, but Jack Sheridan is an Institution,” said the New York Journal in 1914.3

Hall of Fame umpires Bill Klem and Billy Evans concurred: Jack Sheridan was the greatest umpire who ever lived.2 Sheridan worked in major and minor leagues from 1885 to 1914. He was a fearless arbiter in a raucous era and an innovator of umpiring technique. “A ballplayer is merely a ballplayer, but Jack Sheridan is an Institution,” said the New York Journal in 1914.3

John F. “Jack” Sheridan was born on April 30, 1862, in Decatur, Illinois. He was the younger of two children born to Irish immigrants Patrick and Bridget Sheridan. Jack’s sister, Mary, was born in Illinois in 1859. The family moved to Northern California in 1863.4 Census records show that they resided in San Jose in 1870 and in San Francisco in 1880, and Patrick’s occupation was listed as “laborer.”

Jack played second base in the early 1880s for San Francisco teams known as the Renos and the Haverlys.5 In the spring of 1885, he played for the Chattanooga Lookouts and umpired in the Southern League.6 By June he was in New York, and after a trial as a center fielder on a Rochester team, he excelled as an umpire in the New York State League.7 “He is a man of good habits and on ball and strikes and close decisions, it is said, has no superior,” noted Sporting Life.8 Sheridan turned to umpiring after a sore arm halted his playing career.

In the late 1880s, Sheridan umpired in the California League and was regarded as the finest umpire in the state.9 He was well versed in the rules and praised for his integrity. With a cool temperament, he kept rowdy ballplayers in line – he was “sharp with the boys and [did] not stand any nonsense.”10 Major leaguers who played in exhibition games in California recognized his ability. “This man Sheridan is about the best umpire I ever saw,” said Billy Nash of the Boston Beaneaters. “You get just what’s coming to you; no more, no less.”11

Sheridan wed Annie E. Beggs, a native Californian, in February of 1889, and their daughter was born that summer. Sadly, the infant died, and in June of 1890, Annie died after a long illness.12 Sheridan then resigned his position in the California League and moved east to work in the Players League, replacing Ross Barnes, who had resigned in June.13 Sheridan never remarried.

On the Fourth of July 1890, Sheridan umpired his first major-league games in a doubleheader at Pittsburgh. Brooklyn’s John Montgomery Ward collected six hits and scored five runs in the twin bill.14 Throughout the season, Sheridan was paired with veteran umpire John Gaffney, with Sheridan usually working the bases and Gaffney behind home plate. Sheridan “is as good an umpire as ever I saw,” said Gaffney.15

The Players League folded after one season, and Sheridan returned to the California League the next season. In 1892 he worked solo in the National League but did not meet expectations and was let go in July. He was rated the top umpire in the Southern League in 1893, and in the Western League the next two seasons,16 and was rehired by the NL in 1896.

The New York World applauded his work: “Without exception, Sheridan is as good as any umpire that ever officiated in a game. … He is fearless and just, and above all has the respect of the players. He is not a home umpire.”17 It was easy for an umpire to be influenced by a boisterous home crowd; with Sheridan on duty, the visiting team was assured of impartiality. Sheridan was given the honor of umpiring the 1896 Temple Cup championship series between the Baltimore Orioles and Cleveland Spiders.

During this era, players and managers frequently complained about umpires’ decisions. It “is hound, hound, hound [the umpire] about all the time,” wrote sportswriter Jake Morse.18 Umpires were accused of being robbers, cheats, and drunkards, and police were needed to protect them from irate fans, who might storm the field in protest. “This state of things makes it exceedingly difficult to secure good men as umpires,” said Morse. “There is not enough in it for the abuse with which they are showered.”19 In St. Louis, Sheridan was the target of eggs, tomatoes, and cucumbers hurled by spectators. “None was too poor to bring something for the umpire,” he quipped.20

On July 22, 1897, in the first game of a doubleheader at Pittsburgh, Sheridan lost his cool and took a swing at Pittsburgh pitcher Pink Hawley, who had uttered something offensive. Hawley retaliated with “two well-aimed blows” that knocked Sheridan to the ground.21 Nine days later, Sheridan failed to show up for a game in Chicago. He resigned his position because he could no longer tolerate the abuse.22

Ban Johnson, president of the Western League, “crusaded against rowdiness” in his league and supported “his umpires with better pay” and by “backing up their rulings on the field with stiff penalties for bad behavior.”23 He persuaded Sheridan to return to the Western League in 1898. It was a marriage made in baseball heaven. Johnson wanted first-rate umpires and was willing to pay for them, and Sheridan appreciated the supportive environment. Johnson’s minor league was named the American League in 1900, and became a major league the following year. Sheridan worked in the AL for the rest of his career.24

On May 1, 1902, Sheridan ejected the Orioles’ John McGraw from a game in Baltimore. McGraw was hit by a pitch, but Sheridan ruled that McGraw deliberately backed into the pitch and did not allow him to go to first base. McGraw responded with “remarks … about Sheridan that blistered the paint off the press stand.”25 After the game, a dozen policemen protected Sheridan from angry Baltimore fans. McGraw received a five-day suspension from Ban Johnson for the incident.26

In New York on July 7, 1903, Sheridan was arrested by local police after striking Danny Green of the Chicago White Sox. “Sheridan explained that he had ordered Green from the grounds, and the player had refused to leave, but had used indecent and insulting language.”27 Sheridan apologized for losing his temper and was not suspended by Johnson.

The conflict with Green was unusual. Normally, in response to a player’s tirade, Sheridan coolly folded his arms and looked “patronizingly at the player like a mastiff regarding a toy terrier,” and seldom made “any reply other than an amused laugh.”28

But when Sheridan wanted to be heard, he could be heard; his booming voice carried throughout the ballpark. One time he yelled at a group of whining Detroit Tigers “in such a fierce manner that they all ran off to their positions as hard as they could.”29 Sheridan’s deep bass was somewhere between the roar of a bear and an echo of thunder. He bellowed “str-r-r-rk” while lifting his right hand; what he said for a ball was “an unintelligible growl,” but sufficiently distinct from his strike call to be understood.30

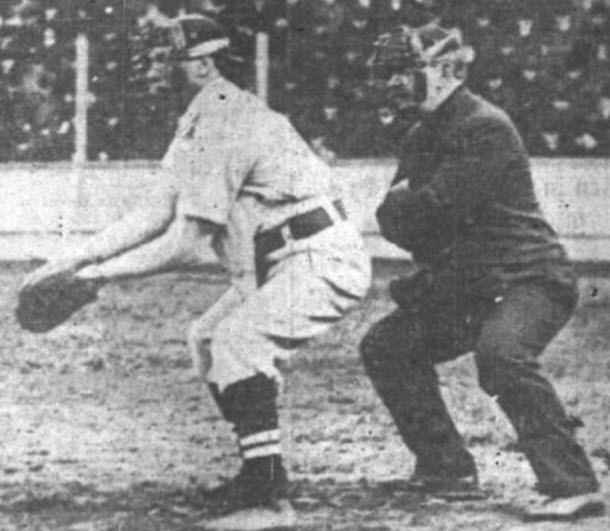

It was the practice at the time for umpires to call balls and strikes while standing straight up. Sheridan introduced the technique of crouching behind the catcher.31 Not only did it give him a better look at the pitch, but he cleverly used the catcher as a shield. This photo of him, which appeared in the April 16, 1905, issue of the Chicago Tribune, shows his posture behind the catcher. Notice how he tucked his hands under his arms, to protect them from foul tips.

It was the practice at the time for umpires to call balls and strikes while standing straight up. Sheridan introduced the technique of crouching behind the catcher.31 Not only did it give him a better look at the pitch, but he cleverly used the catcher as a shield. This photo of him, which appeared in the April 16, 1905, issue of the Chicago Tribune, shows his posture behind the catcher. Notice how he tucked his hands under his arms, to protect them from foul tips.

As can be seen in the photo, Sheridan wore a mask but no chest protector or shin guards. Later in his career, he fashioned a chest protector out of a hotel register and wore it under his coat.32 He did not hold an indicator, preferring to keep track of balls and strikes in his head.

In the offseason Sheridan worked as an undertaker in San Jose, in a joint business venture with his brother-in-law and sister. In the spring of 1905, he announced that the 1905 season would be his last. He and the National League’s Hank O’Day were given the honor of umpiring the 1905 World Series. The New York Giants won the Series, 4 games to 1, against the Philadelphia Athletics. In a span of six days, Christy Mathewson of the Giants threw three shutouts to win Games One, Three, and Five of the Series. Sheridan was the home-plate umpire in each of these shutouts and declared after the Series that “Mathewson is the greatest pitcher the game ever knew.”33

Ban Johnson persuaded Sheridan to return in 1906. He was reportedly the highest-paid umpire in 1907,34 and he was again honored by umpiring the 1907 and 1908 World Series.

In 1906 Sheridan mentored Billy Evans, one of several young umpires he trained for the American League. These are some of Sheridan’s tips for aspiring umpires:35

- Never lose sight of the ball. If you always know who has it, you are not going to lose many plays. Keep your eye on the ball and the rest of it will be easy.

- Don’t make your decisions too quickly. Nothing looks worse than to see an umpire make his decision before the play is actually completed. But once the play is completed, don’t hesitate.

- Be “on top” of every play. The public will excuse many a mistake if it is evident the umpire is making every effort to judge the play correctly by closely following the ball and runner.

- Don’t look for trouble. Don’t go on the ball field with a chip on your shoulder.

- Avoid arguments whenever possible.

- Don’t parade the unlimited authority that is yours. Only as a last resort should you put an offending player out of the game. The public pays its good money to see the stars in action.

- Dismiss your troubles when the game is over. No man can succeed as an umpire and retain his health if he worries.

Sheridan was a part-time umpire from 1910 to 1913. His vision was declining and he began wearing eyeglasses off the field, but he refused to wear them on the field.36 He sought to retire, but Ban Johnson did not want to lose him. Johnson let him work the bases and avoid the more strenuous duty behind the plate. Johnson also gave him breaks from umpiring by employing him as a scout to find up-and-coming umpires in the minor leagues. In 1911 Sheridan received a gold medal from the American League for his contributions. He went on the Giants/White Sox world tour during the winter of 1913-14, during which he umpired exhibition games between the two teams.

In 1914, his final season, Sheridan returned to full-time umpiring work. An unfortunate incident marred his swan song: A fight broke out in the ninth inning in Detroit on July 30, and it was Sheridan who threw the first punch, at the Washington Senators’ Ray Morgan after Morgan threw dirt at him. Johnson suspended Morgan but did not punish Sheridan, which outraged many observers.37 It was remarkable that Sheridan had hit only two players in 15 years, noted the Los Angeles Times.38

Sheridan umpired his final game in Chicago on September 24, 1914. He was ill when he went home to California, and on November 2, 1914, he died of a heart attack in San Jose at the age of 52. He was buried at the Oak Hill Memorial Park in San Jose, beneath a monument with the inscription, “Erected by the American Baseball League in appreciation of his long and valued services.”39 The San Francisco Chronicle reported:

“At his funeral in San Jose many of the men who have made baseball what it is paid their last respects to him. Floral tributes from Presidents Johnson and Tener of the American and National leagues, George Stallings, Connie Mack, Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson and all the mighty men of baseball were received. As long as baseball is played the name of John Sheridan will linger in the memory, and, although the years to come may unfold many luminaries, none will dim the luster of the long and honorable diamond career of the dean of umpires, Jack Sheridan.”40

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Washington Times, December 1, 1913.

2 Jocko Conlan and Robert W. Creamer, Jocko (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 88; Philadelphia Inquirer, December 2, 1929.

3 Reprinted in Sporting Life, August 15, 1914.

4 San Francisco Call, April 7, 1890.

5 Ibid.

6 Atlanta Constitution, May 8 and 14, 1885.

7 Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, June 9, 10, and 23, and October 8, 1885.

8 Sporting Life, November 11, 1885.

9 Sporting Life, December 19, 1888.

10 Sporting Life, December 26, 1888.

11 Sporting Life, December 25, 1889.

12 Ancestry.com; Sporting Life, July 24, 1889; San Francisco Call, June 20, 1890.

13 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 18, 1913.

14 Sporting Life, July 12, 1890.

15 Dighton (Kansas) Herald, January 12, 1899.

16 Sporting Life, August 19, 1893; Atlanta Constitution, May 14, 1894.

17 Reprinted in the Akron (Ohio) Beacon Journal, June 6, 1896.

18 Sporting Life, August 8, 1903.

19 Ibid.

20 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 11, 1897; Baltimore Sun, September 11, 1905.

21 Pittsburgh Post, July 23, 1897; Sporting Life, July 31, 1897.

22 Sporting Life, August 7 and 14, 1897.

23 Joe Santry and Cindy Thomson, “Ban Johnson,” SABR Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/dabf79f8.

24 Hall of Fame umpire Tommy Connolly, another refugee from the National League recruited by Ban Johnson, spent the rest of his career in the American League.

25 Boston Globe, May 2, 1902.

26 Sporting Life, May 17, 1902.

27 Detroit Free Press, July 9, 1903.

28 Sporting Life, September 2, 1905.

29 Detroit Free Press, May 24, 1901.

30 Sporting Life, October 19, 1907.

31 Montreal Gazette, April 28, 1944.

32 Conlan and Creamer, 89.

33 Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 24, 1905.

34 Washington Post, September 22, 1907.

35 Buffalo Commercial, February 2, 1912; Philadelphia Inquirer, December 10, 1929.

36 Washington Post, August 21, 1910; Chicago Inter Ocean, October 25, 1910.

37 Washington Times, July 31 and August 1, 1914; Detroit Free Press, August 1, 1914; Sporting Life, August 8, 1914.

38 Los Angeles Times, August 21, 1914.

39 Sporting Life, September 16, 1916.

40 San Francisco Chronicle, November 29, 1914.

Full Name

John F. Sheridan

Born

April 30, 1862 at Decatur, IL (US)

Died

November 2, 1914 at San Jose, CA (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.