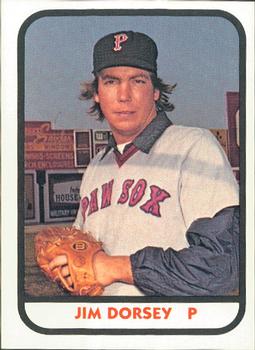

Jim Dorsey

Right-handed pitcher Jim Dorsey spent 11 years in professional baseball, six years in the Angels system and five in the Red Sox system. Both Los Angeles teams had been after him as a prospect. The Angels drafted him out of Grover Cleveland High School in Reseda (California) in the 21st round (486th overall) in June 1973. When he didn’t sign, the Dodgers made him a second-round pick six months later when he was a student at Los Angeles Valley Junior College. Again he didn’t sign. In January 1975 the Angels tried again, making him a second-round pick. This time he signed with scouting supervisor Al Kubski.1

Right-handed pitcher Jim Dorsey spent 11 years in professional baseball, six years in the Angels system and five in the Red Sox system. Both Los Angeles teams had been after him as a prospect. The Angels drafted him out of Grover Cleveland High School in Reseda (California) in the 21st round (486th overall) in June 1973. When he didn’t sign, the Dodgers made him a second-round pick six months later when he was a student at Los Angeles Valley Junior College. Again he didn’t sign. In January 1975 the Angels tried again, making him a second-round pick. This time he signed with scouting supervisor Al Kubski.1

Why hadn’t he signed the first couple of times? “I was just coming out of high school. They drafted me and then they called me and wanted to know what school I was going to. They said, ‘If you want to sign, we’ll send you to rookie ball. We’re not giving you a bonus or anything. We’ll give you a pair of shoes.’ I said, ‘I’m planning on going to college.’ I decided to go to a junior college. I had a couple of opportunities to go to universities, but I decided to go to junior college so I could get drafted again. I wasn’t real studious. I didn’t care about school. I wanted to play baseball. So I ended up going to Los Angeles Valley Junior College.2

“The next draft, I was drafted in the second round by the Dodgers. I said, ‘Wow, why did they waste a pick on me?’ I had tendinitis in my shoulder. I didn’t play through the season. They called me and said, ‘We’ve had scouts out there trying to see what you’re doing.’ I said, ‘I’ve been hurt.’ They said, ‘Okay, well, we’ll talk to you when you get back together.’”3

An outsider might wonder about the quality of the scouting at the time. In the first instance, it seems the Angels didn’t know of his intention to go to college. That said, it was a 21st round pick. In the second instance, however, the Dodgers devoted their second-round selection to him, but hadn’t known he was hurt. The third time could be said to be the charm, but the experience was less then charming. “I did a lot of training and got it back together. I thought I was going to go with the San Francisco Giants,” Dorsey says. “That scout was there all the time. The Angels were going to go for Willie Mays Aikens as their #1 pick. They wanted to sign me before the draft.” Al Kubski came to the house but when he phoned the Angels GM, he was told it was five minutes after 12 o’clock [midnight Pacific time] and that opportunity was gone. “My mom went off on him! She said, ‘Don’t you ever come to this house again.’ My college coach at that time told him, ‘Don’t come to the ballpark any more. Stay out of here.’ It was a terrible experience. And then I got drafted as the #2 pick. By the Angels.”

But he signed. “There wasn’t very much money at that time. I think I got $16,000.”

Jim Dorsey was on his way. He was 6-foot-2 and listed at 190 pounds.

James Edward Dorsey III was born in Chicago on August 2, 1955. The family lived in Oak Park but only until Jim was 2 years old. His father — James Jr. — and mother, Mabel (known as Mae) moved the family to California. Jim’s father worked for Semtech, a company that made diodes and other electronics and the company wanted to expand and set up operations in Westlake, California, south of Los Angeles. He was, Jim understands, the top salesperson in the company and on track to become vice president, but died when Jim was 10 or 11.

Jim was the middle child, with two older sisters (Linda and Debbie), a younger brother (Ed), and then a younger sister (Donna). Raising five children wasn’t easy. Mae Dorsey was beneficiary of a good insurance policy, but became a travel agent and then a secretary. “She did a heck of a job,” Jim said in a May 2020 interview. “We all ended up doing pretty good.” The Angels sent him to Davenport, Iowa, to play for the Quad Cities Angels in the Class-A Midwest League. He got off to a spectacular debut, striking out every one of the first six batters he faced.4 On May 20, after sitting out a one-hour dust storm in the first inning, he threw a seven-inning no-hitter against Clinton in the first game of a doubleheader.5 He put together an impressive first season in 1975 — a record of 15-3 with an ERA of 2.12. He struck out 161 batters and walked 56 in 161 innings. He was named to the league All-Star team, and was the winning pitcher in a game when the league’s all-stars defeated the Triple-A Iowa Oaks.6 At the end of the year, Dorsey was awarded the Win Clark-Citizens Trophy as the top first-year pro in the state of California.7

Jim spent five seasons pitching in winter baseball. It made a big difference economically. His first visit to another country was to a 10-day tournament in Managua, Nicaragua. There were teams from countries such as Colombia and Japan. The Angels sent their instructional league team. “They gave us $900 to go down there for 10 days.”

Dorsey pitched three seasons in Venezuela, one in the Dominican Republic, and one in Puerto Rico. In the minor leagues, his starting pay with Quad Cities had been $500 a month. After his 15-3 season, he says he battled with the Angels right up to the final day of spring training, looking for an increase in pay. “They finally gave me $800 a month — a $300-a-month raise — and they said, ‘Don’t tell anybody, because that’s a lot of money.’ It was unbelievable. Until you got on the major-league roster, then you started making decent money.”

Winter ball, though, paid substantially more. “I was making $6,000 or $7,000 a month. You’d do very well there. They paid for your hotel. They’d give me a rental car if you wanted that. You basically just paid for your food. That’s where I would make money. I would lose money during the season.”8

After his brilliant year with Quad Cities, the opposition was tougher in Double-A ball. Dorsey spent 1976 and 1977 in the Texas League with the El Paso Diablos. He was 9-9 (4.50) with 101 Ks in 164 innings the first year and 10-9 (5.00) in ’77, with 73 strikeouts and 70 walks. One of his big moments in 1976, illustrative of minor-league economics of the time, came when he and Lamar Wright won both games of the June 24 doubleheader against San Antonio, 12-2 and 7-2. Diablos GM Jim Paul “was so happy with the complete-game efforts that he gave each a $20 on-the-spot bonus.”9

In 1978, he started the season again in El Paso but about six weeks in he was promoted to Triple A.10 With the Diablos in 1978, he won five games and lost two, though his ERA was 5.80. The Triple-A promotion placed him in the Pacific Coast League, pitching for the Salt Lake City Gulls. He improved despite being at the higher level, posting an ERA of 3.34 and a won/loss record of 11-7. “I’ve been at El Paso for two years and didn’t have the same mental sharpness I have here. After all, this is just one step away from the majors and I seem to be bearing down more now.”11 At one point he put together a streak of 27 1/3 consecutive scoreless innings. After the season he was placed on the Angels’ 40-man roster.

He spent the full 1979 season with Salt Lake. He walked 100 batters in 168 innings, eight more than the 92 he struck out. He’d gotten off to a good start; at one point he won five in a row in June, but then lost a 1-0 two-hitter to Hawaii on July 2. His record for the year ended up 10-12 (5.52). He enjoyed a final triumph, though, in the playoffs against Hawaii, coming into the deciding game of the PCL championship in the fifth inning and holding the opposition scoreless on just two hits while his teammates overcame a 2-0 deficit to win the game and the title. After the game, he admitted he hadn’t been pitching well and said he understood why he hadn’t been used much in the playoffs. “I guess I didn’t deserve to be there, but I seethed inside. I was pumped up when I got the chance.”12

He improved in 1980, going 14-7 (4.01) for the Gulls and then getting his first taste of major-league action. The Angels had a team ERA of 4.62 at the time he was brought up, the worst ERA in the majors, so it was a good time to try out some new arms.13

Dorsey’s major-league debut was on September 2, 1980, a Tuesday night game at Boston’s Fenway Park. The Red Sox were still in the hunt, in third place 6 ½ games behind the Yankees. The Angels, though, were 32 ½ games behind the AL West-leading Royals in sixth place.

Angels manager Jim Fregosi no doubt thought it was a good time to give Dorsey a start. He retired all three batters in the bottom of the first. In the second inning, he walked Jim Rice, had Tony Perez single Rice to third, and then hit Carlton Fisk with a pitch, loading the bases with nobody out. He got two outs without any scoring, but then Glenn Hoffman and Rick Burleson both doubled, each driving in two runs. With two runners on in the fourth inning, Dave Stapleton tripled to center field and the Red Sox had six runs. Fregosi replaced Dorsey, who bore the loss in a 10-2 game.

Dorsey got three more starts that year. He was “near-perfect” for 3 1/3 innings against the Yankees on September 7, but then gave up a three-run homer to Jim Spencer; he lost, 4-1.14 He picked up his only major-league win on September 12 when the team was back in Anaheim Stadium. The Angels were hosting the Texas Rangers. In the bottom of the first, Larry Harlow’s grand slam capped a five-run rally that staked Dorsey to an early lead. After adding three more runs in the second inning, the Angels had an 8-0 lead. A cluster of three singles in the third and another cluster of a walk and five more singles in the fifth got the Rangers four runs, but Fregosi left Dorsey in to finish the inning and thus be in a position to win. Dave LaRoche was brought in to pitch the sixth and he pitched all four of the final innings in relief, securing the win for Jim Dorsey, who had “barely made it through the fifth.”15 Once again, he’d been strong in his first few innings but then the other team had gotten to him.

A fourth start resulted in a no-decision. At the end of his first year, Dorsey was 1-2 with a 9.19 ERA.

He pitched during the offseason in Venezuelan winter league baseball. And the Boston Red Sox had become interested in him. “Luis Aparicio was our manager in Venezuela and I think that’s how he got my name over to the Red Sox.”

On January 23, 1981, Dorsey was part of a significant trade with the Boston Red Sox. The Angels acquired Fred Lynn and Steve Renko, giving up Joe Rudi, Frank Tanana, and (in the undiplomatic words of Boston Globe columnist Ray Fitzgerald), “undistinguished minor leaguer hurler Jim Dorsey.”16

“This trade may be a break for me,” Dorsey declared. Peter Gammons, though, opined “it’s hard to imagine any pitcher leaving the Angels and thinking he’ll get a better opportunity elsewhere.” Gammons added that the Red Sox “had mixed reports” on Dorsey.17

He was said to have been a disappointment in spring training, as had Bruce Hurst and Win Remmerswaal.18 A writer for the Boston Herald said he was “a longshot even for a spot at Pawtucket.”19 As it worked out, he spent the next three years — 1981 through 1983 — in Triple A with the PawSox, and most of the two years after that.

In 1981, despite a 3.35 ERA he was saddled with a number of tough-luck losses and was 4-10 on the season. “I couldn’t get any runs. I think I had four complete games — all four that I won. I was losing so many games 2-1, 1-0.” He was 5-7 in 1982 and 5-7 again in 1983. Rotator cuff problems hampered him in 1982. His earned run averages were 4.36 and 4.01 respectively. Pawtucket began to use him increasingly in relief (he started 21 games, 13 games, and 1 game in the three seasons.) In 1983, he closed 24 of the 29 games in which he appeared, but lost six weeks to a broken ankle during the season. He was out of action just at the time that other teams were scouting in preparation for the draft. He wasn’t offered another deal and the PawSox were ready to welcome him back, so he signed on again.

In 1984, Dorsey made it back to the big leagues, but not before playing out another full season with Pawtucket. He’d found something of a niche as a short reliever and became the PawSox closer. He had a good year, appearing in 41 games and closing 29. His ERA was 2.91 in 105 1/3 innings (with a 6-4 record and 14 saves). He struck out 83 and walked 49, earning himself elevation to Boston once the International League season was over.

Near the end of the 1984 PawSox season, Dorsey was due to become a seven-year minor-league free agent and, in some senses, it might have been better if he were not added to the Boston roster. When Pawtucket dropped the first two games of the best-of-five playoffs, manager Tony Torchia said he wouldn’t use Dorsey for more than four outs. “He’s already a little tired. He’s going up to Boston when this thing is over, and I want him to do as well as possible. I don’t want him to leave his career here.”20 Dorsey won the semifinal game against Columbus, though, and saved the fifth and final game against Maine.

Dorsey reflected on where he was in his career. “I’ve never had it proven one way or another whether I can or can’t pitch in the big leagues. If I can’t, fine. I’ll go do something else. That’s why I won’t give up.” He said he knew why he’d been labeled as he had: “When you’ve been in Triple-A for seven years, you’re a Triple-A pitcher. Unless you get a shot to perform on the big league level, it’s a label that’s naturally going to follow you.” He added that his more recent success as a reliever had come from being able to throw strikes more consistently in the last two seasons.21 He was aware, he said, that Boston had a lot of younger pitchers on their roster so perhaps a fresh start with another organization would offer more possibilities.22 The Red Sox, though, had stuck with him a long time and saw enough promise that they weren’t prepared to give up yet.

Dorsey appeared in two games for Boston, on September 20 and September 26. It was 7-1 Orioles in the bottom of the fourth. Manager Ralph Houk had seen enough of starter Al Nipper. He beckoned in Dorsey, who closed out the inning, one inherited runner scoring. In the fifth, he gave up a walk, a single, a double, and two more singles — three runs, and the Orioles had an 11-1 lead. Mike Brown took over and allowed four more runs. The O’s won, 15-1. Dorsey had given up the fewest runs of any of the three Red Sox pitchers, but that offered little consolation. His other game was at Fenway Park against visiting Toronto. With a single, a wild pitch, and a walk, it made a big difference when he picked a baserunner off first base and he got out of the eighth inning without allowing a run.

In 1985, it was back to Pawtucket again, sent to minor-league camp in late March. This time he came up for a couple of games midyear — June 29 and July 7. The June 29 game was something of a disaster. The July 7 game was a start.

Just before being called up, he’d become the winning pitcher in something of a marathon game. The game against Syracuse had started on June 19 and ran for 22 innings until curtailed by curfew (the curfew had been implemented after “The Longest Game” — Pawtucket’s 33-inning win over Rochester in 1981). Resumed on June 20, it was halted by rain after 23 ½. Innings. Finally, on the third attempt on June 21, the game was brought to conclusion after 27 innings. Dorsey pitched the final four innings. He was the only player to have been on the PawSox during both of the “longest” games, although he hadn’t pitched in the 1981 game. “They had me warming up in the bullpen at four in the morning in the first game.”23 In 2020 he added, “I couldn’t pitch. I’d pitched like seven innings the night before. Joe Morgan got thrown out, so Mike Roarke took over for us as manager. He said, ‘If this game goes any more, you better go warm up.’ I said, ‘Mike, I’d be lobbing up the ball.’” The 1981 game had been called a little after 4:00 A.M. when someone finally reached the league president and he told them it was okay to suspend the game.

In 1985 Steve Crawford suffered a muscle strain in his back and Dorsey was called up to Boston to take his place while Crawford was on the 15-day disabled list. Dorsey had been used as a starter again — some of the time — at Pawtucket. He had nine starts under his belt. His 71 strikeouts were leading the International League.

On June 29, Oil Can Boyd surrendered six runs to the Orioles through the first four innings. The O’s had a 7-3 lead when Dorsey took over. A walk, a stolen base, and a single gave Baltimore one more run in the fifth. In the sixth, though he got a couple of outs, he gave up four singles and then a double and saw three runs score. Red Sox manager John McNamara called in Mark Clear, and the first batter he faced doubled, resulting in two more runs being charged to Dorsey. The Orioles were red hot; they got to Clear for three more runs before the inning was over.

Roger Clemens was due to pitch in Anaheim on July 7, but felt a pain in his shoulder while in the bullpen just before the game. With only minutes to prepare, Dorsey was asked to start. “I didn’t find out I was starting until the National Anthem,” he said later.24 With two singles, a double, and another single, he was fortunate to only give up one run in the bottom of the second. It would likely have been worse but one of the runners (Bobby Grich) was erased when Marty Barrett executed a hidden ball trick at second base. Then, Larry Whiteside wrote, “Dorsey turned right around and did the things that will most likely earn him a trip back to Pawtucket. In the bottom of the third, he gave up a solo home run to Ruppert Jones….Then, with two out in the fourth, Dorsey gave up a walk and a two-run homer to Reggie Jackson before walking three more batters and giving way to [Tom] McCarthy.” He had walked eight batters in the game, and given up six earned runs. It was his last game in the majors.

The Red Sox acquired Tim Lollar and Dorsey returned to Rhode Island, rejoining Pawtucket. It was, a Los Angeles Times writer noted, his 11th year of trying to stick in the big leagues. Tony Torchia said, “Jim Dorsey is definitely a study in perseverance… Last year at Pawtucket, I thought he was a major league prospect, and I told him so. I’m a very big fan of Jim’s.” Rich Gedman added, “He definitely has the good arm and mind to make it in the big leagues. The thing is, once you’ve been here and then sent back down, like Jim, you can get a little anxious to try and prove yourself overnight.”25

Dorsey looked back on the memories and said, “Sure you go through some rough times and get discouraged, but it’s a heck of a job and I’m having fun doing it. I’ve spent a lot of time in this game and most of it has left me with good memories. Pitching at Yankee Stadium on the Game of the Week. Beating Texas for my only victory when I was with California. Those were real thrills. . .There’s one thing I can tell you: I’m going to keep going until someone tells me I can’t anymore.”26

On November 14, 1985, he was released by the Red Sox.

In his fielding, he had rather few chances in the majors (five); he was error-free in the 1980 and 1984 seasons, but committed an error in the only chance he had in 1985, a throw to second base on July 7 to try to thwart a stolen base. In his minor-league seasons, he had an .866 fielding percentage.

He was 102-85 as a pitcher in the minor leagues, with a career 4.05 ERA across all levels.

As far as baseball goes, Dorsey reflected: “I don’t really have any regrets. I was fortunate to play for 11 years in the minor leagues. You had to be pretty good to stick around that long. The biggest problem that I had was that I couldn’t throw a third pitch. I couldn’t master the changeup. But I was a two-pitch pitcher, with an average fastball. I threw about 90 miles an hour. I think the hardest I ever threw was like 92. I had a real good curveball. That was my best pitch.

“I think that I jumped up the ladder really quick. I played the last eight years in Triple A — which was nice. But I was always that guy — ‘OK, if somebody gets hurt, you’re going up.’ It’s not like I didn’t get a chance. But the chances I had when I was up there, I walked too many people. I ran scared. I ran scared instead of just doing what got me there. I thought I had to be the person who threw every pitch on the corner, and you don’t have to be like that. The years when I did have bad years, it was control issues.”

After the 1985 season, Jim married Deborah Santos. “She was from Pawtucket. I met her while I was playing at Pawtucket and then we got married right after the season.” Coming up on 35 years of marriage at the time of the 2020 interview, Dorsey said, “That was the best thing that happened. If I hadn’t pitched those years at Pawtucket I never would have met her. So I guess things do work out.”

The couple has two children — a daughter Noemi, 32, who is a supervisor for a Community Action Program in Western Massachusetts tutoring underprivileged children, and a son, Sean, 29, who is a software engineer for IGT. “He is married to our lovely daughter-in-law Amanda. They have one child, our beautiful little granddaughter, Aurielle, who is 18 months old.”

Jim and Deborah live in Seekonk, Massachusetts.

Deborah works as a legal secretary. Jim retired in 2018 after 31 years as a driver for United Parcel Service. “I was a driver at UPS. I started there one year after I got out of baseball. I had worked two winters — one winter out here in Rhode Island and one winter out in California. Just as part-time jobs. Just for Christmas time. So I knew the work. I said, ‘It’s not bad. It’s not something I want to do the rest of my life, but it’s a job.’ The pay was always good. The pension right now is great.

“The only thing I regret there is that I missed a lot with the kids. The Little Leagues and stuff like that. I didn’t get home until 8 o’clock every night. That was the worst thing. My wife worked also but she basically ran them to all the soccer games and baseball games.”27

Jim gets to Fenway Park maybe once a year when the Red Sox host alumni at a specific game. This gives him the opportunity to meet old friends and teammates and catch a little baseball, often with his son Sean — even if Sean is a Yankees fan.

Last revised: August 25, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Andrew Sharp and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org. Thanks to the Boston Red Sox.

Notes

1 See photograph featuring Dorsey and Kubski in the December 27, 1975, issue of The Sporting News on page 55.

2 Author interview with Jim Dorsey on May 25, 2020. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations attributed to Dorsey come from this interview.

3 Author interview. See also Ron Rapoport, “Westmoreland No. 1 Name on Dodgers’ Puny Draft List,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1974: 34.

4 “Record 6,486 Turnout for West Palm Opener,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1975: 39.

5 “Quad Cities’ Jim Dorsey Flips Midwest No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1975: 44.

6 Jerry Jurgens, “Midwest’s Moundsmen Stymie Triple-A Oaks,” August 2, 1975: 39. He was one of seven pitchers used. The Oaks didn’t get a hit until there were two outs in the eighth.

7 The Sporting News, December 27, 1975: 55.

8 The conditions themselves were sometimes spartan, however. “When you had batting practice, they don’t put the lights on because if they put the lights on, it takes up too much electricity from the city. When I was in Caracas for three years, the first time I was out there, there was no lights on but the place was packed.”

9 “Texas League,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1976: 38.

10 He wouldn’t want to remember the April 18 game against Amarillo when he had a no-hitter going through 7 1/3 but then completely collapsed. The one single in the eighth wasn’t bad, but the seven runs on eight hits in the ninth were discouraging. Fortunately, El Paso had been holding a 15-0 lead. “Dorsey Loses His Stuff,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1978: 34. Not long after he joined Salt Lake, he threw a three-hitter against Hawaii on June 3.

11 “Dorsey Bears Down,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1978: 36.

12 Ray Herbat, “Title Heroes at Salt Lake,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1979: 38.

13 “Angels Keep the Bosox Rolling,” Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1980: E2.

14 “Rudy May Finds the Angels Don’t Score Much,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1980: D9.

15 John Weyler, “Angels Pick On Rangers Again,” Los Angeles Times, September 13, 1980: D2.

16 Ray Fitzgerald, “The Lynn Trade — Act of Desperation,” Boston Globe, January 24, 1981: 1.

17 Peter Gammons, “Trade Pleases Dorsey,” Boston Globe, January 26, 1981: 34.

18 Peter Gammons, “A Red Sox Assessment,” Boston Globe, April 8, 1981: 79.

19 Steve Harris, “Lockwood, Dorsey Fail; Sox Bow, 10-9, Boston Herald, March 22, 1981: 29.

20 Peter Gammons, “Baseball, for the Love of Baseball,” Boston Globe, September 12, 1984: 29.

21 Peter Gammons, “Show Time for Dorsey,” Boston Globe, September 15, 1984: 25.

22 Gammons, “Show Time for Dorsey.”

23 Associated Press, “PawSox Capture 3-Day Marathon,” Hartford Courant, June 22, 1985: D6B.

24 Dave Desmond, “Running Behind Schedule,” Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1985: v_b18.

25 Desmond.

26 Desmond.

27 In an email on May 27, Dorsey offered another regret: “In looking at current salaries, I feel that I was about 15 years too early.”

Full Name

James Edward Dorsey

Born

August 2, 1955 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.