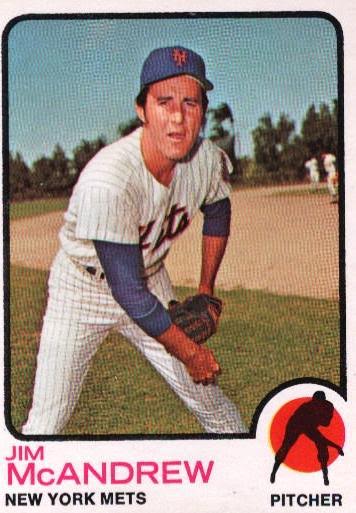

Jim McAndrew

Twenty-five-year-old Jim McAndrew emerged from spring training 1969 to start the second game of the year for a New York Mets team that boasted one of the game’s top young rotations. Yet due to a series of misfortunes, injuries, and bad luck—a continuation from the previous year where the Mets were shut out in his first four major league starts — McAndrew did not record his first victory until June 24. Finally healthy in August, McAndrew pitched six inning or better in nine straight starts, including back to back shutouts and tying the club record with 23 straight scoreless innings. A skinny and unheralded prospect from Iowa farm country, McAndrew provided Mets management with more than they expected, though he never quite rose to the ranks of heralded teammates Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, and Nolan Ryan.

James Clement McAndrew was born on January 11, 1944 in Lost Nation, Iowa, a farming community of less than 600 residents about 50 miles west of Davenport to Clement James (Clem or C.J.) McAndrew and the former Loretta Hart. His father grew corn and raised chickens on 750 acres. Jim was the oldest of four and grew up with three sisters, one of whom, born in December 1944, was his Irish twin. He began playing Little League at age nine and by his freshman year in high school stood only 5 feet tall and weighed a mere 95 pounds.1 He was 17 when he graduated from high school and had grown to 5-feet-11, although he still weighed only 135 pounds. McAndrew played varsity basketball and baseball well enough to draw the attention of the University of Iowa, where future NCAA executive director Dick Schultz was the baseball coach. St. Louis Cardinals scout Kenny Blackman also came for a look and they discussed signing a contract, but Blackman told him that with his size he would be better off going to college and developing his game there.

McAndrew wanted a college education and matriculated to the University of Iowa. He played baseball and basketball until he hurt his knee during the basketball season in his sophomore year. The injury convinced him that he should stick with baseball. He had pitched and played shortstop in high school but was never a great hitter and so decided his best shot would be as a pitcher.2 But he favored his bad knee and hurt his arm in the spring before his junior year. He missed the season and that summer tried unsuccessfully to pitch for Rapid City in the Basin League, a summer college circuit.3 Although McAndrew could not fully straighten his arm, he found that he could pitch without pain for his senior year at Iowa. He had also finally grown to his full 6’2” height. He pitched well but finished 4-4 for the Hawkeyes. One of his starts was against Ohio State’s top prospect Steve Arlin in Iowa City. McAndrew lost to Arlin and the Buckeyes, 2-0, on two unearned runs. He did, however, spark interest of scouts from the Cubs and Mets, who were at the game to watch Arlin (the Ohio State right-hander would be drafted in the first round by the Phillies the following year).4

Upon the recommendation of scout Charley Frey, the Mets drafted McAndrew in the 11th round of baseball’s inaugural draft in 1965. Nolan Ryan was chosen by the Mets one round later and both he and McAndrew were assigned to Marion, Virginia in the rookie-level Appalachian League. After two solid starts, McAndrew was promoted to the Auburn, New York, in the Class A New York-Penn League. There in 11 starts he finished 5-5 but with an unpromising 5.37 earned run average. McAndrew was sent to the fall instructional league, where Bob Scheffing, Mets director of baseball operations, took him under his wing. McAndrew credited Scheffing with straightening him out and teaching him how to pitch.5 Scheffing later admitted that at the time McAndrew “had absolutely no market value.”6

After finishing his psychology degree at Iowa in the offseason, McAndrew was back with Auburn in 1966. He improved to 11-7 with a respectable 3.61 ERA. McAndrew and future Mets teammate Jerry Koosman led the club to an 80-49 mark that took the pennant by eight games. McAndrew’s performance with Auburn earned him a promotion to the Eastern League and the Double-A Williamsport Mets for 1967. He continued his advancement by posting a 10-8 mark and a minuscule 1.47 ERA that led the league and was almost four full runs less than his first year as a pro. In 153 innings he allowed only 119 hits. He also started against a future Hall of Famer. Robin Roberts, who at 40 was trying to make a comeback with the Reading Phillies, beat McAndrew that day, 5-3, but he retired from baseball after that outing.7

Even with his strong showing in 1967, the Mets did not protect McAndrew from the minor league draft that winter. No other organization selected him and McAndrew gave serious thought to retiring from baseball. He had married his college sweetheart, Lyn, right after his graduation from Iowa and now had a son. It was difficult supporting a family on a minor league salary so Jim thought it was time to stop bouncing around and put his college degree to use.8 Lyn, however, persuaded her husband to give baseball another try.9

The Mets assigned McAndrew to the Triple-A Jacksonville Suns of the International League for 1968. In spring training one day, he felt tearing in his elbow and feared that he had reinjured his arm. It turned out that lesions from the old injury had finally broken loose, enabling him to straighten his right arm for the first time in years. It added about a foot to his fastball and also enabled him to improve his breaking pitch.10

Jacksonville manager Clyde McCullough still was not impressed and McAndrew began the International League season in the bullpen with a very sporadic workload. Whitey Herzog, the director of player personnel for the Mets, thought McAndrew had major league potential. When he learned that McAndrew was languishing in the bullpen, he ordered McCullough to put him in the starting rotation.11 When the manager did not follow instructions, Herzog nearly fired him for insubordination.12 McAndrew finally got his start and flourished, becoming the team’s ace. After just six starts, on July 21 the Mets called him up for an emergency start.

Unfortunately, McAndrew’s big league debut drew Bob Gibson and the defending world champion Cardinals; in St. Louis, no less. Gibson was in the middle of a remarkable season in which he won the Cy Young Award with a 22-9 record and put together a 1.12 ERA, the lowest in the National League since 1906. In six innings on a sweltering afternoon, McAndrew allowed only an inside-the-park home run by Bobby Tolan, helped by some shaky fielding in the Mets outfield. He left the game having allowed only that run and the Mets were eventually blanked by Gibson, 2-0.13 It was one of 13 shutouts Gibson tossed that year, the most in the NL since 1916.

The following day, McAndrew was headed back to Jacksonville as planned. In what would be his last start for the Suns, he had a perfect game after five innings when McCullough pulled him. McAndrew soon learned, however, that he was headed back to the Mets and was scheduled to start two days later when Nolan Ryan left the club for his two-week active military duty.14 McAndrew finished in Jacksonville with an 8-3 record and a 2.54 ERA in 117 innings. He never pitched another minor league inning for the Mets.15

His second major league start was in Dodger Stadium against Mike Kekich, who picked that evening to pitch a one-hit shutout. McAndrew again lost, 2-0. Next, against the Giants in Candlestick Park in San Francisco, he ran into Bob Bolin, who tossed a four-hit shutout at the Mets, this time a 1-0 defeat. It got no better in McAndrew’s fourth start, his Shea Stadium debut. This time the Astros beat him, 1-0, as Don Wilson and John Buzhardt combined on a four-hitter. Four starts and the Mets had yet to score a run. McAndrew was 0-4 with an earned run average of 1.82. Welcome to “Year of the Pitcher.”

The luckless McAndrew drew Juan Marichal for start number five. The Mets finally scored some runs behind him and he actually held an early 2-1 lead, but San Francisco roughed up the rookie and he wound up losing his fifth straight game, 13-3.

For his sixth start, on August 26, McAndrew drew young Cardinals left-hander Steve Carlton. He tossed a five-hit shutout as the Mets scraped together a run in the eighth inning on a single to left by Tommie Agee, a sacrifice bunt by Phil Linz, a steal of third, and a sacrifice fly to right by Cleon Jones. McAndrew made the game’s lone run hold up and finally had a victory. In his third start against a future Hall of Famer—and 300-game winner to boot—McAndrew was finally in the winner’s circle.

McAndrew continued to pitch well after his hard luck 1-5 beginning and won three more games while losing two for the rest of the year. His totals for the ninth-place Mets in 1968 were 4-7 in 12 starts with a sparkling 2.28 earned run average. In five of those losses, the Mets did not score but he pitched shutouts himself in two of his wins.

McAndrew went into 1969 spring training with high hopes, but his bad luck continued and he caught the flu late in spring training after getting a flu shot. Then, when he flew to New York to join the team, he was picked up at the airport by a friend who drove him to a restaurant for dinner. Jim’s luggage was in the back seat of the car and was stolen while he was eating dinner. The theft wiped out his wardrobe.16

His bad luck still wasn’t over. In his first start in the second game of the year, he was knocked out in the second inning by a batted ball up the middle that struck the middle finger of his pitching hand. He spent so much time with his finger in the whirlpool that he softened the skin. As a result, the next time he pitched he developed a blister on the finger. McAndrew then spent the month of May soaking the finger in pickle brine to toughen the skin, a remedy that Nolan Ryan had used successfully.17 McAndrew was anxious to get back on the mound, but he hurt his shoulder while pitching batting practice and trying to relieve pressure on his finger.18

At the time, McAndrew developed something of an inferiority complex because he didn’t throw particularly hard or have great stuff, especially compared with Seaver, Koosman, Ryan, or touted rookie Gary Gentry. McAndrew, who had taught in Job Corps, also had doubts whether throwing a baseball had any value to society in the tumultuous ’60s. Manager Gil Hodges told McAndrew that what mattered were results and that the best pitcher he had ever seen was Whitey Ford, who didn’t throw as hard as McAndrew. A visit with an uncle who was an executive at Pfizer convinced Jim that ballplayers were entertainers who provided real value to society.19

Still, by late June, McAndrew had a 0-2 record for the year. He pronounced that he was sound and won two straight starts to even his record. On July 6 he didn’t make it out of the first inning at Pittsburgh. Afterward Gil Hodges had a heart-to-heart talk with the pitcher, telling him that he was being selfish and hurting the team by trying to pitch when his arm was still sore.20

McAndrew learned his lesson, and in early August he threw seven shutout innings against the Atlanta Braves. Now healthy, he reeled off nine starts covering 73 innings and pitching to a 1.60 ERA. He threw three straight complete games, including the 23 consecutive shutout innings.

Still, the Mets had such depth in starting pitching that most of McAndrew’s starts down the stretch came in doubleheaders where the Mets needed an extra starter. One of those games came on September 10 against the Montreal Expos at Shea Stadium with the Mets tied with the swooning Cubs. McAndrew pitched 11 crisp innings before being lifted with the score tied, 2-2. The Mets won in the 12th on an RBI single by Ken Boswell. With the Cubs losing their seventh straight that afternoon to the Phillies, the Mets were in first place. His last start of the year was another no-decision that went extra innings, a win over the Cardinals that put the Mets one game from capturing the NL East title.

McAndrew did not appear in the playoffs or World Series. His record in his first full major league season was 6-7 with 21 starts and 27 appearances. He had a 3.47 ERA in 135 innings, above the team’s 2.99 ERA but below the league’s average.

McAndrew started the 1970 season as the club’s number three starter behind Seaver and Koosman and ahead of Gentry, who had pitched the third game in both the NLCS and World Series for the 1969 Mets. McAndrew continued to be plagued by poor run support and his own inconsistency.21 By early July, he was only 3-6 in 13 appearances—nine starts—with two complete games. He was relegated to the back of the rotation, but in the dog days of August and then September, McAndrew pitched consistently well, as he had in his first two seasons. McAndrew finished with a 10-14 mark and 3.56 ERA in 27 starts and five relief appearances, covering 184 innings. Five of his losses were by one run, further cementing his reputation as a hard-luck pitcher.

McAndrew’s luck only worsened in 1971. In early May, he collided in the outfield with Gentry while shagging fly balls in pregame warmups. He woke up in the hospital with 38 stitches in the side of his head and top of his ear.22 Although he was not placed on the disabled list, McAndrew was inconsistent as a starter and had trouble holding leads.23 By early June was out of the rotation and in the bullpen. Two starts in August still left him winless for the year against five losses.24 He again pitched well late in the year and picked up wins in both of his September starts to finish 2-5 with an unwieldy (for the times) earned run average of 4.38. He threw just 90 innings for the season but surrendered only 78 hits, indicating that he still had good stuff.

McAndrew finally reversed his history of slow starts in 1972 after beginning the season in the bullpen under new manager Yogi Berra, who had taken over following the shocking death of Gil Hodges. McAndrew got his second start in May against the Montreal Expos and won, 2-1, the first of four wins in a row. Even though he was having the best year of his career, he still had to endure a 21-day stretch in July when he did not take the mound at all.25 It was not because of injury or his performance but rather due to outstanding starting pitching during that stretch by Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Jon Matlack, and Gary Gentry.26 He started the year 9-3 and faded a little down the stretch to finish 11-8, though he still had a sharp 2.80 ERA for the third-place Mets. In 28 appearances and 23 starts he threw 161 innings and allowed just 133 hits.

McAndrew began the 1973 season as the number four starter behind Seaver, Koosman, and Matlack—Gentry had been traded to Atlanta. Because of a light early-season schedule, McAndrew did not get his first start until the season was a week old and then never could get untracked. Although the Mets squeaked to the National League East with only an 82-79 record, McAndrew was never a factor, finishing with a 3-8 record and a 5.38 ERA in just 80 innings. George Stone, who came from the Braves with Felix Millan in the Gentry deal, had been the anchor on the back end of the rotation. McAndrew did not make an appearance in the postseason as the Mets defeated the Cincinnati Reds in the NLCS before losing to the Oakland A’s in seven games in the World Series.

It was clear that McAndrew no longer fit in the Mets plans and shortly before Christmas of 1973 the club traded him to the San Diego Padres for Steve Simpson, a minor leaguer who had one season in Double-A with the Mets before calling it a career.27

McAndrew’s career was also drawing to a close. Although he reported to spring training with high hopes, more bad luck awaited with the Padres. Pitching coach Bill Posedel expected the pitchers to take part in “rundown” or “hotbox” drills in which the infielders practiced getting runners out in rundowns between the bases. Because of his chronically bad knee, McAndrew tried to beg off and just run in the outfield, but Posedel would have none of it. Sure enough, he reinjured his knee in a hotbox situation, with a pop that could be heard all over the infield.28

Although the club physician recommended surgery, Jim opted to ice the knee for several days, which had generally worked before. He then strained his ribs while trying to pitch and was never able to get healthy.29 McAndrew struggled to a 1-4 record in 15 appearances and five starts when the Padres released him on June 1. Although just 30 years old, his baseball career was over.

He made 161 major league appearances, including 110 starts, 20 complete games, and six shutouts. He pitched 771 innings and gave up less than a hit per inning, with 712 hits allowed. His seven-year career totals were 37 wins, 53 losses, and a 3.65 ERA.

McAndrew had a growing family to support and didn’t look back after his release by the Padres. He began a career in sales and management in the coal industry and within a year and a half was making more than the $45,000 that was his top salary in baseball.30 He was first in Chicago for five years, then in Denver for 15 years, and St. Louis for eight years.31 He and his wife, Lyn, raised four children, Jamie, Jeff, Jon, and Jana. Jamie, the oldest, was a first-round draft choice in 1989 out of the University of Florida and pitched for the Milwaukee Brewers for two years in the 1990s.

After more than 25 years in the coal industry, Jim was able to retire at the age of 56 and settle in the Phoenix area with his wife.32

Last revised: May 22, 2019

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “The Miracle Has Landed: The Amazin’ Story of how the 1969 Mets Shocked The World” (Maple Street Press, 2009), edited by Matthew Silverman and Ken Samelson.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Durso, Joseph. Amazing—The Miracle of the Mets (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1970).

Fox, Larry. Last to First—The Story of the Mets (New York: Harper & Row, 1970).

Golenbock, Peter. Amazin’—The Miraculous History of New York’s Most Beloved Baseball Team (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002).

Koppett, Leonard. The New York Mets—The Whole Story (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1970).

Oppenheimer, Joel. The Wrong Season (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1973).

Ryczek, William, The Amazin’ Mets—1962-1969 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2008).

Shatzkin, Michael, ed., The Ballplayers (New York: William Morrow and Co., Inc. 1990).

Sullivan, Bill, Long Before the Miracle: The Making of the New York Mets (Self-published, 2016).

Vecsey, George. Joy in Mudville (New York: McCall Publishing, 1970).

Zimmerman, Paul, and Dick Schaap. The Year the Mets Lost Last Place (New York: World Publishing, 1969).

Notes

1 Joe Donnelly, “Patience Rewards Lost Nation With Victory,” Newsday, August 27, 1968.

2 Leigh Riley, “Ex-Farm Boy Jim McAndrew Now Baseball Clothes Horse,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1969: 7.

3 Author interview with Jim McAndrew, December 18, 2008.

4 McAndrew interview.

5 Wilks, “Mets McAndrew Almost Quit After Having 1.37 ERA in “67,” undated clipping from the St. Louis Post Dispatch from the Jim McAndrew clippings file, National Baseball Library; Riley; McAndrew Interview.

6 Jack Lang, “Gentry Is Met Flop of Year, McAndrew the No. 1 Hero,” unidentified clipping dated September 2, 1972 from the McAndrew clippings file.

7 Robin Roberts with C. Paul Rogers III, My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003), 212-13; Joe Trimble, “Think Met Hurlers: You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet,” New York Daily News, July 26, 1968: C22.

8 Wilks; Donnelly, “Patience Rewards Lost Nation With Victory.”

9 McAndrew interview; see also Jim Smith, “Lyn McAndrew: Typical Baseball Wife,” unidentified clipping dated July 29, 1970 from the McAndrew clippings file.

10 McAndrew interview.

11 Jack Lang, “McAndrew and Ryan Top Question Marks on Met Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1969; Donnelly, “Patience Rewards Lost Nation With Victory.”

12 McAndrew interview.

13 Joe Donnelly, “One Game by Met Rookie Puts Lost Nation on Map,” Newsday, July 22, 1968: 33.

14 Donnelly, “Patience Rewards Lost Nation With Victory.”

15 Trimble.

16 Jack Lang, “Flu, Duds Stolen . . . McAndrew’s Bad Week,” unidentified clipping dated May 3, 1969, McAndrew clippings file.

17 Jack Lang, “2 Unhappy Met Hurlers . . . All They Do Is Win,” unidentified clipping dated September 2, 1969, McAndrew clippings file.

18 Steve Jacobson, “McAndrew Is No Cheerleader Now,” unidentified clipping dated August 21, 1969, McAndrew clippings file.

19 McAndrew interview.

20 Lang “2 Unhappy Mets Hurlers”; Jacobson.

21 Paul Ballot, “A Twisting Spirit,” unidentified clipping dated July 7, 1970, McAndrew clippings file.

22 McAndrew interview.

23 Joe Gergen, “Prosperity Spoils Mets McAndrew,” Unidentified clipping dated May 6, 1971, McAndrew clippings file.

24 Joseph Durso, “Mets’ McAndrew Battling to Gain His First Victory,” New York Times, September 5, 1971.

25 Red Foley, “Mets Call on M’Andrew to Halt 3-Game Slide,” New York Daily News, August 5, 1972; Phil Pepe, “Mets Leaving It Up to McAndrew Again,” New York Daily News, August 16, 1972.

26 “Mets One Closer (It’s a Start),” unidentified clipping dated August 16, 1972, McAndrew clippings file.

27 Red Foley, “Mets Deal M’Andrew for 1-7,” unidentified clipping dated December 24, 1973, McAndrew clippings file.

28 McAndrew interview.

29 McAndrew interview.

30 Don Laible, “McAndrew on Being Mets’ Royalty, and After Baseball,” Utica Observer-Dispatch, December 13, 2016.

31 McAndrew interview.

32 McAndrew interview. In 2016 McAndrew’s grandson Max and Duffy Dyer’s grandson Drew formed the battery at Brophy College Prep in Phoenix. Dyer had caught McAndrew in the minor leagues and with the Mets many years before. https://nysportscene.com/2016/mcandrew-dyer-battery-strikes/

Full Name

James Clement McAndrew

Born

January 11, 1944 at Lost Nation, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.