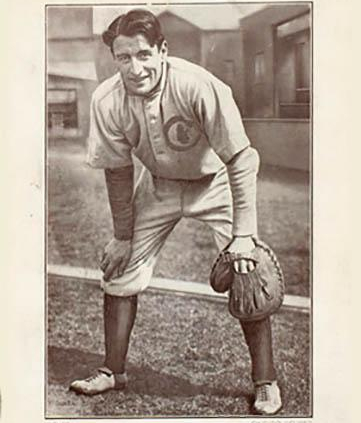

Jimmy Archer

Jimmy Archer was the regular catcher for the Chicago Cubs from 1911 through 1916, earning a spot on Baseball Magazine‘s “All-America Team” each year from 1912 to 1914. Renowned for popularizing the snap throw from a squatting position, Archer enjoyed a reputation for having the best throwing arm of any catcher in the Deadball Era. “The best throwing catcher of them all was Jimmy Archer of the Cubs,” said Chief Meyers of the New York Giants, the only receiver aside from Archer to catch over 100 games each season from 1911 to 1913. “He didn’t have an arm. He had a rifle. And perfect accuracy.” Al Bridwell, the ex-Giant shortstop who played with Archer on the 1913 Cubs, agreed. “Best arm of any catcher I ever saw,” said the man who received many of Archer’s snap throws. “He’d zip it down there to second like a flash. Perfect accuracy, and under a six-foot bar all the way down.”

Jimmy Archer was the regular catcher for the Chicago Cubs from 1911 through 1916, earning a spot on Baseball Magazine‘s “All-America Team” each year from 1912 to 1914. Renowned for popularizing the snap throw from a squatting position, Archer enjoyed a reputation for having the best throwing arm of any catcher in the Deadball Era. “The best throwing catcher of them all was Jimmy Archer of the Cubs,” said Chief Meyers of the New York Giants, the only receiver aside from Archer to catch over 100 games each season from 1911 to 1913. “He didn’t have an arm. He had a rifle. And perfect accuracy.” Al Bridwell, the ex-Giant shortstop who played with Archer on the 1913 Cubs, agreed. “Best arm of any catcher I ever saw,” said the man who received many of Archer’s snap throws. “He’d zip it down there to second like a flash. Perfect accuracy, and under a six-foot bar all the way down.”

James Peter Archer was born in Dublin, Ireland, on May 13, 1883. His family moved to Montreal when he was an infant, and by the time he was three the Archers had settled in Toronto. Jimmy played baseball at St. Michael’s College and in the Toronto City League. During the winter of 1902, the 19-year-old Archer was working as a barrel maker at a cooperage in Toronto when he fell into a vat of boiling oak sap, scalding his right arm and leg so badly that he was hospitalized for three months. Jimmy was in so much pain during his hospitalization that he begged for his arm to be amputated. As a result of the accident, the tendon in his right arm shrunk and made his right arm shorter than his left. Jimmy was left with a unique strength; he always claimed that the accident was what gave him his unique ability to throw quickly and accurately from a squatting position.

Archer’s career in professional baseball began when a friend, Tom Reynolds, invited him to join the team from Fargo, North Dakota, that he was managing in 1903. Under no contract and making little money, Jimmy batted .225 in 20 games before jumping to an independent team in Manitoba that offered more money. The following year he played in the Iowa State League with Boone, where he met his future wife, Lillian Stark. His season was briefly interrupted when he broke his collarbone by crashing into a hitching post while chasing a pop fly, but he returned in time to hit .299 in 72 games. Near the end of 1904 Archer received a September trial with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Making his major-league debut on Labor Day, he appeared in seven games, all of them second games of doubleheaders, and managed three singles in 20 at-bats.

The Pirates optioned Archer to Atlanta of the Southern Association in 1905, where he cracked his kneecap when Bugs Raymond crossed him up with a curve after he had signaled for a fastball (they sewed it back together with two silver threads). He spent two seasons with the Crackers, hitting .254 and .224, and in 1907 he received a second chance at the majors with Detroit. Serving as third-string catcher behind Boss Schmidt and Freddie Payne, Archer batted a paltry .119 and caught only 17 games during the regular season, but he got the start in Game Five of that year’s World Series because the Cub base runners were having a field day at the expense of the other two Tiger catchers. The Cubs stole three bases off of Jimmy, but two came on a “walking” double steal in which no throw was made. Though hitless in his three at-bats against Mordecai Brown, who pitched a shutout, Archer did manage to cut down Jimmy Slagle, Chicago’s leader in stolen bases with six during the Series, at second base in the seventh inning.

In 1908 Detroit manager Hughie Jennings tried to teach Archer to take a step towards the base when he throws, the way most catchers do, but Jimmy preferred his natural “flat-footed” method. Concluding that the young catcher was uncoachable—and also not much of a hitter—Jennings decided to release him, though he later admitted that it was the only player-release decision he ever regretted. Clark Griffith, then managing the New York Highlanders, said that he never would have permitted Archer to leave the American League if he hadn’t been at his ranch in Montana when Detroit requested waivers. “If I had that fellow I’d work him every day just to watch him peg,” said Griffith. “There is not another man in his class when it comes to shooting the ball. He is faster than chained lightning, and he never has to take a step to get the ball to any of the bases. Kling isn’t in it when it comes to keeping the runners glued to the bags.”

Alas, Griffith was in Montana and Archer did clear waivers, so Jennings sent him to Buffalo where he batted just .208 in 82 games in 1908. One of those games occurred on an off-day for the Chicago Cubs as they were traveling east, and manager Frank Chance stopped off in Buffalo to scout George McConnell, a spitball pitcher who was tearing up the Eastern League. Around the fourth inning a friend who was with the Peerless Leader asked, “Well, what do you think of the pitcher?” “Pitcher!” exclaimed Chance. “It’s the catcher I’ve been watching.” Months later the Cubs manager learned that Archer had risen from a sickbed that day because the other Buffalo backstops had refused to catch McConnell’s spitter. When star catcher Johnny Kling elected to hold out, Chance remembered the gritty Buffalo backstop and purchased him to share the catching duties with Pat Moran.

Archer caught 80 games in 1909 and improved his batting average to .231, but Kling returned in 1910 and reclaimed the starting position. Archer caught 49 games that season and spelled Frank Chance at first base in another 40, raising his batting average to .259 and showing some power (30% of his hits were for extra bases). In the 1910 World Series, Kling started at catcher for the first three games, with Archer seeing action at first base in Game Three after Chance was ejected. Archer started at catcher for the final two games, as Kling was criticized for calling too many fastballs with men on base. Jimmy played well in Game Four, the only Cubs victory, scoring the winning run after doubling in the 10th inning, but in the decisive Game Five he allowed four stolen bases and the A’s won easily.

Archer supplanted Kling as the first-string catcher in 1911, prompting the Cubs to trade the popular Kling to Boston in June. Jimmy remained the primary Cubs backstop through 1916, putting together his best season in 1912 when he batted a career-high .283 and led the National League in assists. He remained the NL’s premier catcher through 1914, when he broke his arm crashing into a concrete wall in Brooklyn and was arrested in October for assaulting a fan he thought was annoying his wife (charges were dropped a week later). He shared the catching duties with player-manager Roger Bresnahan in 1915 and three other catchers in 1916. In 1917 the Cubs released the 34-year-old Archer when he refused to take a pay cut. He was the last remaining player from the Frank Chance era.

Jimmy agreed to help out the Pirates during spring training in 1918, but he quickly earned first-string status and started on Opening Day. Pittsburgh released him after he hit only .155 in 24 games. Brooklyn picked up Archer for nine games and then sold him to Cincinnati, where he closed out his career by appearing in nine more games. After suffering 14 broken fingers, Jimmy felt that his hands could no longer take the punishment.

After his baseball career, Archer returned to the Chicago area and worked for Armour and Company, buying hogs. In 1931 he received a medal for reviving two workers who had fallen unconscious from carbon monoxide poisoning. An outstanding bowler, Jimmy served as the promotional director for the Congress of Professional Bowling Alleys. He also was the commissioner of the Chicago softball league and remained active in the Old-Timer’s Baseball Association. Archer died from a coronary occlusion on March 29, 1958, in a Milwaukee hospital where he was being treated for tuberculosis of the spine. He is interred in his wife’s hometown of Boone, Iowa, where he played in 1904. In 1990 Jimmy Archer was elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

NOTE: An earlier version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D. C.: Brassey’s Inc., 2004).

Sources

Ethan Allen. Major League Technique and Tactics. MacMillan, 1938.

Lawrence Ritter. Glory of Their Times. MacMillan, 1966.

New York World, 10/15/1914, 10/23/1914, 1/10/1917, 2/22/1917, 5/31/1917, 7/11/1917.

New York Evening Telegram, 5/29/1909, 7/15/1913.

New York Herald, 9/17/1912.

Baseball Magazine, Dec. 1912, Feb.1913, Dec.1913, Oct. 1917

Baseball Digest, Feb.1944

Letter to J.C. Simoni from Mrs. Walter Stark

1930 U.S. Census

Wisconsin State Board of Health Death Certificate

New York Times, 3/31/1958

Jimmy Archer file at the Baseball Hall of Fame library

The Sporting News, miscellaneous clippings.

Full Name

James Patrick Archer

Born

May 13, 1883 at Dublin, Dublin (Ireland)

Died

March 29, 1958 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.