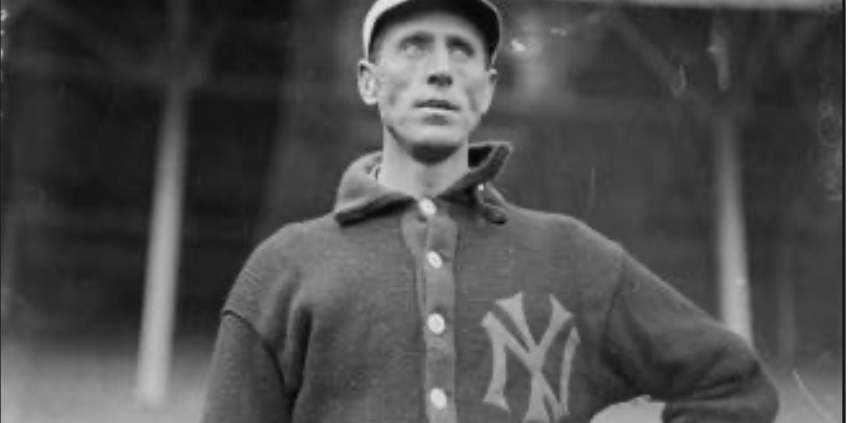

George McConnell

While appearing in only 176 major-league games over six seasons, George McConnell split his time among three leagues (American, Federal, and National) and between two positions requiring different skill sets (first base and pitcher). McConnell’s versatility hampered his development, because he could not focus on pitching until after he had passed his athletic peak. A subpar performer in the NL and AL, McConnell starred as a pitcher in the minor leagues and Federal League, playing a starring role in helping the Chicago Whales win the 1915 Federal League pennant by the narrowest of margins.1

While appearing in only 176 major-league games over six seasons, George McConnell split his time among three leagues (American, Federal, and National) and between two positions requiring different skill sets (first base and pitcher). McConnell’s versatility hampered his development, because he could not focus on pitching until after he had passed his athletic peak. A subpar performer in the NL and AL, McConnell starred as a pitcher in the minor leagues and Federal League, playing a starring role in helping the Chicago Whales win the 1915 Federal League pennant by the narrowest of margins.1

Tall for his era at 6-feet-3,2 McConnell, born in 1877 in Shelbyville, Tennessee, to Neely and Martha Jane McConnell, began his professional career as a first baseman because his size would allow him to reach more hits and throws.3 He played for two Central League teams, the Dayton Veterans and the Wheeling Stogies, in 1903 and 1904. Under manager Ted Price, McConnell led the Stogies with a .318 batting average in 1904. Neither Price nor McConnell would return to Wheeling in the same roles in 1905: “It is said that the reason George McConnell will not sign with Wheeling is because he was not appointed manager. The Stogies will miss George and his big stick.”4

Instead, McConnell joined the Johnstown Johnnies of the Tri-State League in 1905 before beginning a three-year run with the Buffalo Bisons of the Eastern League in 1906. After his first season, Sporting Life described McConnell as “Buffalo’s clever first baseman … the tallest player in the Eastern League this year, [who] did some of the tallest playing.”5

The available data show that McConnell struggled with the bat in 1906 but had a “deadly wallop”6 in 1907, when he led the Bisons in hits, doubles, batting average, slugging percentage, and total bases. In spite of these marks, Buffalo in the 1907 offseason decided to move McConnell, “said to be a master of the ‘knuckle’ ball,”7 from first base to the pitching mound.8 As a hitter, McConnell had attracted no notice from the majors, but the Chicago Cubs looked him over four months into his pitching career.9

Impressively, McConnell won 17 games for the 1908 Bisons; more impressively, the 1908 Cubs had a staff that threw consecutive shutouts in closing out Chicago’s second consecutive World Series win over Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, and their 1908 Detroit teammates. The Cubs did not need another pitcher, but the New York Highlanders did. New York finished last in the American League in 1908 with a 51-103 record and a league-worst 3.16 ERA. (For context, the AL as a whole had an ERA of 2.39 in 1908.) The Highlanders had a new manager for 1909 in George Stallings, who would win fame with the 1914 Miracle Braves. Having managed McConnell in Buffalo in 1906, Stallings knew McConnell the player if not McConnell the pitcher.

Stallings got New York to buy McConnell, now noted as having “something new in the line of a spit ball,” from the Bisons.10 In spring training “the first delivery he employed when he sent them down from his lofty height with an overhand swing. The ball seemed to be coming from out of the azure sky. The telescopic twirler then changed to an underhand delivery. His repertoire also included a slow ball. …”11

An attempt at vigilante justice marred McConnell’s preseason. The Highlanders trained in Georgia, where McConnell lost some personal items. In response, “McConnell and several of his comrades secured a rope and threatened, it is said, to string up a negro bellboy on whose person the stolen artifacts were found. Detectives Smith and Harrison interfered and locked the negro up. McConnell is from Anderson, S.C.”12

The article ends without additional comment, implying that since McConnell came from the South he might have killed an African-American hotel worker for an alleged theft. The incident took place less than one month after the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and about a decade before the birth of Jackie Robinson.

McConnell debuted in New York’s second game of the 1909 season. He batted fifth and played first base. He singled twice, scored a run, and made two errors as the Highlanders blanked the Senators, 5-0. Stallings needed a first baseman because Hal Chase had come down with smallpox.13 In spite of this promising beginning with the bat, McConnell did not hit well enough to justify his batting-order slot. Stallings hit McConnell fifth 10 more times in 1909 even though he went just 7-for-38 for a .184 batting average in this role.

After Chase returned, McConnell made his pitching debut against Detroit on June 8. Stallings picked a big moment for his rookie hurling, putting him into a tie game in the ninth. McConnell pitched two shutout innings before giving up the winning run in the 11th. Walking one and fanning three, McConnell “was calm under fire, had scorching smoke and good control.”14

Stallings started McConnell two days later against the Tigers, and he lacked the command that he had displayed in relief. Lasting just one inning, McConnell gave up two hits, two walks, and one run. He threw a wild pitch and balked for the first and only time in the majors. A month later, New York tried to sell McConnell to the Jersey City Skeeters of the Eastern League,15 but the Boston Red Sox put in a waiver claim on him, canceling the transaction.16 After getting McConnell through waivers, the Highlanders sent him to the Rochester Bronchos of the Eastern League.17

Stallings likely gave up so quickly on McConnell because “he could not hold runners on the paths. He insisted on taking a windup when the paths were populated. … [H]e has overcome this fault, and [by 1911] he held men closer to the sacks than any other twirler in the Eastern League.”18

After his up-and-down 1909 campaign,19 McConnell starred for Rochester in 1910 and 1911. On September 5, 1910, McConnell no-hit the Toronto Maple Leafs to highlight a 19-12 season. He topped that by going 30-8 in 1911. “In July 1911 he was repurchased by … New York … for between $8,000 and $10,000, the condition of the sale calling for him to join the New Yorkers at the end of the Eastern League season. … [T]he tall flinger has mastered a new delivery since his former trial with the Yankees which has wonderfully improved his pitching.”20

In returning to New York, McConnell may have also improved an off-speed pitch. He “uses the spit ball, but not exclusively, and in the last year has developed a better curve ball than he used to have.”21

McConnell finally played full-time in the majors in 1912, albeit for the worst team in terms of winning percentage in Yankees history. In spite of an 0-5 start, he finished 8-12 and with a staff-best 2.75 ERA. McConnell tied the AL record for pitcher assists in a game with 11 in a 1-0 loss to the eventual world champion Boston Red Sox on September 2.22He would have seemed to have a promising future if not for the calendar as “he is but a year younger than [Christy Mathewson], of whom the fans are beginning to speak as if he already had one foot planted in the grave.”23

The 1912 Cleveland Naps had a young pitching staff and sought to add the veteran McConnell for the 1913 campaign. Cleveland manager Joe Birmingham “decided that he would give up, man for man, or even two for one, if he could secure the big pitcher. Owner Frank Farrell, of the Yankees, was all attention when Birmingham hinted that he had a prospective trade. … But when Joe mentioned McConnell’s name the Highlanders’ owner smiled and winked the other eye.”24

Staying with New York, McConnell started the 1913 opener in Washington. In the best year of his career in which he would go 36-7 with a 1.14 ERA, Walter Johnson opposed McConnell. “The latter outpitched the Washington star”25 as the Yankees led 1-0 going into the bottom of the seventh. McConnell “pitched gilt-edged ball. … The Senators’ winning rally started when [Eddie] Ainsmith apparently stepped into a ball directly over the plate. The umpire allowed him to take first base whence his teammates pushed him around for the home team’s first run [of two in the inning].”26 The phantom hit batter allowed Washington to win 2-1, but the unheralded McConnell nearly matched the masterful Johnson pitch-for-pitch:

IP H R ER BB SO HR BFP

McConnell 8 7 2 2 2 2 0 36

HBP: McConnell (1)

Johnson 9 9 1 1 1 3 0 36

HBP: Johnson (1)

Through July 4, McConnell had a record of 4-10 with a 3.61 ERA. By the end of the season, his ERA had dipped to 3.20, but he lost his last five decisions to finish 4-15. McConnell’s losing streak did not diminish Cleveland’s interest in him. New York manager Frank Chance, who had scouted McConnell in 1908, “asked for nothing more or less than little Nemo Leibold and pitcher George Kahler.”27 In late August, less than a month after this report appeared in print, McConnell’s season ended because of an injury inflicted by one of these players; “Leibold hit a hard liner at McConnell and the ball struck the New York pitcher on the right hand. It broke the third finger of his pitching hand so badly that the bone protruded through the flesh.”28

McConnell never pitched for the Yankees again. He spent most of 1914 back with Buffalo, where the St. Louis Browns had sent him after picking him up on waivers from New York.29 He pitched the second game of the 1914 season for the Bisons against a pitcher making his professional debut: “‘Babe’ Ruth, the sensational young southpaw … plucked from the sand lots to make good his first year out in the professional ranks, held Buffalo safe all the way. Big George McConnell … was rapped hard and timely by the home team, while his support was also rather wobbly.”30 McConnell lost the game, 6-0.

Again he suffered a major late-season injury, this time “a torn ligament in his pitching arm, sustained on Labor Day.”31Bought by the Cubs from the Bisons,32 McConnell recovered sufficiently to start a game during the last week of the season. He gave up one run over seven innings but lost 2-0 to the St. Louis Cardinals. In spite of his brief time in Chicago, McConnell, along with two teammates, was “up in arms because they were counted out of any part of the Cubs’ end of the Chicago City Series money and all are talking … of going over to the Federals, the haven of many a disgruntled player.”33

The talking turned into jumping. After flirting with the FL’s Buffalo Blues,34 McConnell joined the Chicago Whales instead. The president of the Whales wrote the president of the Cubs asking for payment for his pitcher, pleading, “‘I feel that you should reimburse us for our investment in the services of … McConnell.’ In a nutshell, [Cubs President Charles] Thomas proposes to sell a player to the outlaw league. Such a thing is unheard of in baseball.”35 Although Thomas threatened a lawsuit36 and wrote a second letter on the topic,37 the Whales declined to pay for McConnell.

Debuting with the Whales in relief, McConnell, “mixing a good spitball with a terrific fast ball,”38 got a win in his first FL appearance. Also throwing a “mud ball,”39 he soon joined the starting rotation. McConnell led the 1915 FL in wins with 25 (he had 10 losses) and winning percentage at .714. He enjoyed a nine-game winning streak that seemed destined to end at six games on June 30 when Newark had a 6-1 lead on Chicago going into the ninth. The Whales rallied for five runs to tie the score. McConnell loaded the bases with none out in the bottom of the 11th but escaped via a foul out and a double play.40 Chicago won 7-6 in the 12th.

On the last day of the season, Chicago had a doubleheader against Pittsburgh, whom they led by a half-game. One win would give the Whales the pennant; a sweep would put the Rebels in first. McConnell started the first game and needed only one more out to preserve a 4-1 lead and clinch the title for Chicago. McConnell and the defense of the Whales faltered. “[Les] Mann and [Dutch] Zwilling lost their heads, chasing a little fly and let[ting] it drop for a hit. Through the opening thus afforded Pittsburgh rushed three runs home, tying the battle.”41 McConnell failed to finish the ninth, and the Rebels won 5-4 in 11 innings. But Chicago rebounded to win the second game and the pennant.

After the FL’s demise, the Cubs acquired McConnell and 11 other Whales. In 1916 he started strongly, yielding just one earned run in his first three starts, all of which he completed. On April 23, McConnell beat the Pirates, whose lineup featured future Cooperstown immortals Max Carey and Honus Wagner, with a one-hit shutout. Only Jimmy Viox reached, via a double and a walk, breaking a streak in which McConnell “had pitched twenty-six innings without giving a pass.”42

McConnell started 3-1 but finished 4-12. “In the spring when the days are chilly McConnell has few superiors among the major league pitchers,” wrote Sporting Life. “He is not so effective under a burning sun, but he can certainly pile up victories in cold weather.”43 A reporter attributed his fade to “too much preparedness. Anxious to show … good intentions, he … reported … in magnificent mid-season condition. For some weeks he was the best, most effective pitcher in the National League—and now he’s … shot to pieces. He got into shape too soon, and tired in June instead of September.”44

McConnell may have tired in June and struggled during what would become a career-closing nine-game losing streak because of the way manager Joe Tinker used him. On June 28, McConnell pitched 17 innings against Pittsburgh, taking a 3-2 loss in a game that lasted 18 innings. He next pitched on July 8 and threw 10 innings in another loss. Over the two games, McConnell yielded just 17 hits in 27 innings.

In his final game, something of a microcosm of his career, McConnell and Chicago faced Jeff Pfeffer at Brooklyn, the eventual winner of the 1916 NL crown. In a 1-1 game in the bottom of the fifth, McConnell faced the bottom of the Brooklyn order. He walked Mike Mowrey and hit Chief Meyers. A passed ball advanced the runners to second and third for Pfeffer, who “delivered a slow single to center”45 that plated both runs in a game McConnell lost 4-1.

McConnell’s nine-game losing streak of 1916 mirrored his nine-game winning streak of 1915 although his statistics during the two streaks do not diverge as much as one might expect:

Dates G IP H ER BB K ERA W-L

6/6/1915-7/8/1915 10 74.1 59 17 17 33 2.06 9-0

6/15/1916-9/26/1916 16 93.1 82 31 18 41 2.99 0-9

Wins and losses, both in streaks and over seasons, give an imperfect sense of pitcher performance. McConnell pitched worse than his 25-10 record for a first-place team in 1915 indicated and better than his 4-12 mark for a fifth-place team in 1916 suggested. In his final year in the majors, McConnell set a career best with a 1.004 WHIP.

In 1917, McConnell pitched for the Kansas City Blues of the American Association, which banned the spitball in 1918. Accordingly, the Blues sold McConnell to the Little Rock Travelers of the Southern Association.46 His 1964 obituary reports that McConnell went “on the voluntarily retired list in June, 1918. He and a brother, the late Jack McConnell, then opened a photographic studio which he operated in Chattanooga until his death. His wife, Mrs. Elizabeth P. McConnell, and two daughters, Mrs. Emily Herron and Mrs. Arthur Yates, survive.”47 In 1905 McConnell had first married Lucy Gilmer, a union that likely resulted in McConnell’s son, “a very bright little boy of 5,” according to a 1913 article.48

A classic 4A player, McConnell had years of dominance in the minor leagues and Federal League but made little lasting impact in either the NL or AL.

Notes

1 For a detailed look at the 1915 Whales, see Mark S. Sternman, “The Last Best Day: When Chicago Had Three First-Place Teams,” sabr.org/research/last-best-day-when-chicago-had-three-first-place-teams (accessed May 31, 2018).

2 One brief says McConnell “measures 6 feet 5 inches in height.” “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1909: 5.

3 “No man in the business has anything on … George McConnell, now playing first base for the New York Highlanders, when it comes to handling wide thrown balls.” “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, May 8, 1909: 7.

4 “Central League Chatter,” Sporting Life, May 6, 1905: 15.

5 “News Notes,” Sporting Life, October 20, 1906: 8.

6 “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, July 6, 1907: 7.

7 “News Notes,” Sporting Life, April 4, 1908: 3.

8 “Eastern League Notes,” Sporting Life, November 23, 1907: 8.

9 “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, August 8, 1908: 13. In 1908, Chicago “manager Frank Chance stopped off in Buffalo to scout George McConnell, a spitball pitcher who was tearing up the Eastern League.” Bill Bishop, “Jimmy Archer,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/c89dee76 (accessed May 31, 2018).

10 Wm. F.H. Keelsch, “Metropolitan News,” Sporting Life, November 21, 1908: 10.

11 “Young Pitchers at Work,” New York Times, March 3, 1909.

12 “Merely a Scare Intended,” Sporting Life, March 20, 1909: 7.

13 “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, April 17, 1909: 8.

14 E.H. Simmons, “New York News,” Sporting Life, June 19, 1909: 6.

15 “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, July 10, 1909: 11.

16 “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1909: 11.

17 “Condensed Dispatches,” Sporting Life, August 7, 1909: 2.

18 W.S. Farnsworth, “Pitcher M’Connell Is ‘Hope’ of Yanks,” New York Evening Journal, February 5, 1912. In a 1915 Federal League game, Newark’s Al Scheer “stole second on McConnell in the fourth. He was so far on his way that [Chicago catcher William] Fischer didn’t even throw.” “Notes of the Whales,” Chicago Tribune, August 13, 1915: 9.

19 Baseball-reference.com has no 1909 data for McConnell (see baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=mcconn001geo, accessed May 31, 2018), but Sporting Life reveals that he pitched in 13 games with a 9-3 record that allowed him to tie for the EL lead with a .750 winning percentage. In 106 innings, McConnell gave up 72 hits and 22 walks while striking out 74. McConnell played 12 errorless games at first base, but made three errors in his 15 games as pitcher. Sporting Life, January 22, 1910: 11. Playing in 25 games, McConnell went 22-for-84 for a .262 batting average. He had six doubles, one triple, and one homer. Sporting Life, January 22, 1910: 10.

20 This unattributed July 27, 1911, article comes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s file on McConnell. Thanks to Reference Librarian Cassidy Lent for scanning the McConnell file.

21 “The Highlanders,” Sporting Life, January 13, 1912: 5.

22 See baseball-almanac.com/rb_pias.shtml (accessed June 6, 2018). McConnell might own the record outright had he not also made two errors in the game.

23 Henry Dix Coles, “New York News,” Sporting Life, March 23, 1912: 6. While McConnell was born nearly three years before Big Six, during his career he represented his birth date as 1883 rather than 1877, according to unattributed statistical profiles in the Hall of Fame’s McConnell file.

24 Ed Bang, “‘Nap’ Pitchers,” Sporting Life, December 28, 1912: 11.

25 Paul W. Eaton, “At the Capital,” Sporting Life, April 19, 1913: 3.

26 Henry Dix Coles, “New York News,” Sporting Life, April 19, 1913: 1.

27 Ed Bang, “Naps’ Pennant Chances,” Sporting Life, August 2, 1913: 5.

28 “Yankees Continue in Losing Streak,” New York Times, August 26, 1913.

29 Unattributed October 1913 article from the Hall of Fame’s McConnell file.

30 “International League,” Sporting Life, May 2, 1914: 14.

31 “International Items,” Sporting Life, September 26, 1914: 17.

32 “3,000 had been spent by … Chicago … on McConnell, $2,500 of which was paid to … Buffalo … for him, and $500 in railroad fares and training expenses.” “May Enjoin McConnell,” New York Times, April 7, 1915.

33 “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, November 7, 1914: 8.

34 “Feds Not After Cubs’ Pitcher,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1915: B3.

35 Handy Andy, “Thomas Wants Feds to Pay for M’Connell,” Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1915: 11.

36 “The M’Connell Case,” Sporting Life, April 17, 1915: 9.

37 “Thomas Writes Another Letter,” Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1915: 9.

38 “Notes of the Whales,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1915: 13.

39 “Notes of the Whales,” Chicago Tribune, August 6, 1915: 9.

40 Sam Weller, “Whales Score 5 Runs in Ninth; Win in Twelfth,” Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1915: 13.

41 J.J. Alcock, “Whales Win Pennant as 34,000 Fans Cheer,” Chicago Tribune, October 4, 1915: 13.

42 “Nine Zeroes Cubs’ Gift to Pirates,” New York Times, April 24, 1916.

43 “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, May 6, 1916: 7.

44 “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, July 8, 1916: 4.

45 “Superba Pitchers Helped Beat Cubs,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 27, 1916.

46 “Little Rock Gets McConnell,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1918: 1.

47 “George N. (Slats) McConnell,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1964: 42. According to his death certificate, McConnell died of cardiac arrest.

48 “The Son of His Father,” Sporting Life, November 22, 1913: 14.

Full Name

George Neely McConnell

Born

September 16, 1877 at Shelbyville, TN (USA)

Died

May 10, 1964 at Chattanooga, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.