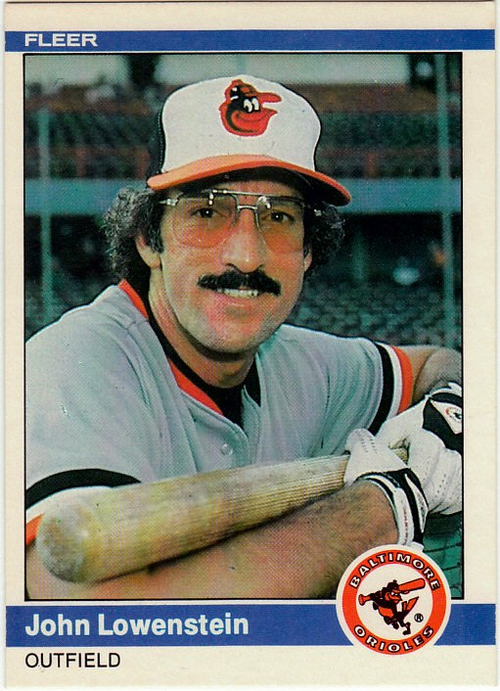

John Lowenstein

When Baltimore broke though in 1979, ending New York’s stranglehold on the American League East title, the postseason was a new experience for John Lowenstein. Since the year he broke into the majors with Cleveland in 1970, “Steiner” had been on two teams that played .500: Cleveland in 1975 and Texas in 1978.

In Game One of the 1979 ALCS, the Orioles were deadlocked at 3-3 with the visiting California Angels. With O’s runners on first and third in the bottom of the tenth inning, manager Earl Weaver sent up the left-handed-hitting Lowenstein to pinch-hit for shortstop Mark Belanger. Angels reliever John Montague threw two forkballs for strikes, and he hit the third pitch over the left-field wall for a three-run homer. The record crowd of over 52,000 at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium went into delirium, calling for Lowenstein to take a curtain call. “The third pitch might have hung a little on the outside corner and I got the bat on it,” Lowenstein explained. “It was a slice to the opposite field and I wasn’t sure whether it would stay fair or have the distance. But the wind kept it in and it just cleared the left-field wall.”1 Montague summed it up by saying, “It was a bad pitch only because it was up and he hit it out.” 2

Weaver was so excited he ran out to second base to greet Lowenstein and escort him to home plate. “I never saw such a little man in the baseline,”3 Lowenstein quipped.

John Lee Lowenstein was born on January 27, 1947, in Wolf Point, Montana. He was the oldest of three children born to Balzer and Duane Lowenstein. John’s sister, Linda, and his brother, Jerry, completed their family of five. Balzer served in the military, stationed in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He was a Golden Gloves champion and served as an athletic adviser and coach after his days in the service. He also worked for Clark County Automotive.

By John’s high-school days, the family had relocated to Southern California. Lowenstein played shortstop at Norte Vista High School in Riverside. After high school he attended the University of California at Riverside. He earned a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and starred on the baseball team. In 1968, he batted .393 and was named shortstop on the NCAA All-American second team.

After three years in college, Lowenstein was selected by Cleveland in the 18th round of the June 1968 amateur draft. His first stop was Class A Reno in 1968 and 1969. Lowenstein fulfilled his military obligation when his Marine Reserve unit was called up to active duty, causing him to miss the first 3½ months of the 1969 season.

Despite his limited minor-league action, Lowenstein earned a promotion to the Wichita Aeros of the Triple-A American Association for 1970. He batted.295 and hit 18 home runs. “I honestly don’t know what we would do without John,” said Aeros manager Ken Aspromonte. “He’s playing short, third, all the outfield positions. He’s hit the ball, made the plays, taken the extra base, everything anyone could ask.”4

Lowenstein earned a late season call-up to Cleveland, collecting his first major-league hit on September 9, 1970, off Washington’s Joe Coleman in the seventh inning. The hit produced his first big-league RBI.

While Lowenstein was in Wichita, he met Barbara Schlotfelt, of Augusta, Kansas. They were married on February 11, 1971. Lowenstein broke camp with Cleveland but returned to Wichita in late May and was recalled in August. Just as Aspromonte used Lowenstein with the Aeros, Cleveland managers Al Dark and Johnny Lipon plugged him in wherever he was needed. He started 25 games at second base, and filled in at shortstop and all three outfield positions.

Aspromonte moved into the Indians dugout as the new skipper in 1972. Jack Brohamer won the starting job at second, but Aspromonte vowed to give Lowenstein every opportunity to win the right-field job. “When a club loses 102 games as the Indians did last season, how can it have a set lineup?”5 the manager said.

Lowenstein was labeled a “utility” player for most of his time with the Indians. But he filled the position well. In 1974 the Indians dealt Walt Williams to the New York Yankees as part of a three-team trade. Williams’s departure opened the door for Lowenstein to start in left field. His ability to play multiple positions proved valuable to the Indians. Third baseman Buddy Bell missed two stretches of games with injuries, and Aspromonte plugged Lowenstein in at the hot corner. Lowenstein started 28 games at third and another 85 in left field. On playing third base, he said “At third base I can hear the fans yelling at me when I miss a ball and I can pick out those fans and yell right back at them. In left field, you don’t know who is yelling at you. Let’s face it – it’s impossible to be humble out there.”6

Lowenstein led the team in stolen bases with 36 in 1974, showing another part of his game that was a valued commodity. In the second game of a doubleheader against Minnesota on June 16, he was a one-man wrecking crew. He went 3-for-4 with two RBIs and four stolen bases in the Indians’ 3-1 victory. “There are so many intangibles in victory. I have always considered myself an intangible asset to a team. Perhaps because the tangible assets of my career are not so impressive,” he said.7 Lowenstein hit .242 in 1974, a batting average he would duplicate in 1975 and 1977.

Lowenstein often shared his thoughts and sharp wit on just about any subject. For instance, he loathed fan clubs. “I don’t believe in fan clubs,” he remarked. “What are they for? Does a player have to have one? I think they are a waste of people’s time. A youngster should be out self-educating himself in other pursuits besides running a fan club.”8

One fan club he showed his support for was the Lowenstein Apathy Club (LAC). Hundreds of letters arrived to the Indians pledging disinterest in his career, some signed with invisible ink. Its members promised to have a day in his honor when the Indians were on the road. Occasionally a banner was unfurled in the upper deck at Municipal Stadium, with “Hey Steiner,” followed by 20 feet of blank white cloth. “There is great solace in not caring,” Lowenstein explained jokingly. “People today are so uptight about everything – war, gasoline, unions – that having complete apathy about something would be welcomed. In a small way, I can bring a moment of peace to my fellow man. Apathy clubs may sweep the nation.”9

The 1977 season meant expansion in the American League as Seattle and Toronto fielded teams. During the expansion draft, Toronto tabbed Cleveland’s designated hitter Rico Carty as a selection. Realizing they had made an error in not protecting the popular Carty, Cleveland shipped Lowenstein and catcher Rick Cerone to the Blue Jays on December 16 to get the right-handed power hitter back. Two days later, Cleveland acquired Johnny Grubb, Hector Torres, and catcher Fred Kendall from San Diego for George Hendrick. When Grubb came up with strained knee ligaments in spring training, the Indians sent Torres to Toronto to reacquire Lowenstein.

Lowenstein explained what he believed to be one of the great international trades of all time, insisting that the United Nations had to give their approval of the deal. “A Mexican (Torres) to a Canadian team (Toronto) for a Jewish gringo (me) to a tribe of Indians (Cleveland). Now figure that out. It’s a three-nation deal at least. It involves money as well, pesos, Canadian, and American money. In fact, I’m the first Jewish Indian traded for a Mexican.”10

The irony was that Lowenstein was not Jewish. The Municipal Stadium organist would serenade him with “Hava Nagila” when he came to bat, until Lowenstein let the organist know he was actually a Roman Catholic. After that, the theme song for his at-bats was “Jesus Christ Superstar.”

The following offseason, Lowenstein was traded along with relief pitcher Tom Buskey to the Texas Rangers for designated hitter Willie Horton and pitcher David Clyde. He spent 1978 with the Rangers, again serving as a utility player, batting .222 with 16 stolen bases. He was placed on waivers after the season and was picked up by Baltimore for $20,000. “We tried to get him for a long time from Cleveland but every time we talked to the Indians about him, they’d ask for one of our top pitchers, like Dave McNally or Mike Cuellar,” Weaver said.11

Lowenstein split his time in 1979 starting in both left and right field on a part-time basis. A severely sprained left ankle in early August curtailed his playing time. The ankle still troubled him somewhat during the postseason. But Lowenstein was able to contribute three hits, one of them a pinch-hit double that drove in two runs in Game Four of the World Series. The Orioles held a commanding 3-1 lead over Pittsburgh, only to drop the final three games and lose the series.

One of the more memorable moments in Orioles history occurred at home on June 19, 1980, against Oakland. But it is not something that will be found in the box score. In the bottom of the seventh inning, Steiner pinch-hit for second baseman Lenny Sakata and singled to right field off Rick Langford. When he attempted to stretch a single into a double, Athletics first baseman Jeff Newman’s errant throw struck Lowenstein in the back of the head. John lay motionless at second base as trainers worked on him. He was placed on a stretcher, and as he was being carried to the dugout. Lowenstein sat up and pumped both fists in the air. The 15,000 spectators, who had been silently looking on, burst into cheers. “You have to acknowledge the cheers of the fans and I sure as hell wasn’t going to come back out after the game,” Lowenstein explained.12

Lowenstein provided reporters with ample hilarity. Some of his quotes:

- On baseball: “Baseball is reality at its harshest. You have to introduce a fictional reality to survive.”

- On birthplaces: “You never know where you are born. You have to take your parents’ word for it.”

- On home runs: “I have noticed that there are a lot of outfielders in the American League with great mobility, and the best way to immobilize them is to hit the ball over the fence.”

- On being a role player: “I have endeavored to retain a low profile in baseball. The organization has been more than helpful in that direction.”

- On statistics: “Nuclear war would render all baseball statistics meaningless.”

- On failing to get a bunt down: “Sure, I screwed up that sacrifice bunt, but look at it this way. I’m a better bunter than a billion Chinese. Those suckers can’t bunt at all.”

- On staying ready on the bench: “I flush the john between innings to keep my wrists strong.”13

Earl Weaver instituted a platoon system in left field, starting Lowenstein against right-handed pitchers and Gary Roenicke against left-handers. He used similar platoons with Al Bumbry and John Shelby in center field and with Jim Dwyer and Dan Ford in right. “I wasn’t comfortable with it because that is pretty much all that I did the rest of my career,” Roenicke said. “But we were such a dynamic and good team that I didn’t want to rock the boat and complain about just me. We were victims of our own success.”14

On a lighter note Lowenstein commented, “I glance at the lineup card, I look for length. If I see a very long name, I know I am playing. I also see a misspelled name. Earl always puts the “i” before the “e.” Sometimes I’ll correct it, but the next day it’s still misspelled.”15

The Orioles and Lowenstein each enjoyed terrific seasons in 1982. Lowenstein had his best year offensively, smacking 24 homers to go with 15 doubles, 66 RBIs, and a .320 batting average. Combined with Roenicke’s 21 home runs and 74 RBIs, Weaver got a lot of production from the left-field position.

Joe Altobelli assumed the managerial duties in 1983 after Weaver retired. On August 13, 2½ games separated Detroit, Baltimore, Milwaukee, New York, and Toronto. But the Orioles put together a 33-9 record to pull away from the pack and claim the division title.

“Everyone says Earl was the smartest manager I ever played for, but I think Altobelli was the smartest because he did nothing when he took over,” Lowenstein said in commenting on the season. “He just put that lineup up in the dugout and sat down next to it and made his pitching changes. He relied on the team and let it fly, and that was smart, because we were fine-tuned to win in ’83, and he recognized that and didn’t screw it up.”16

The Orioles continued their winning ways in the playoffs. In the ALCS, Baltimore lost the opener at home to Chicago, then won three straight to claim the pennant. Likewise in the World Series, Baltimore dropped Game One to the Philadelphia Phillies, then won four in a row to be crowned world champions. In Game Two Lowenstein went 3-for-4, including a home run off Phillies starter Charlie Hudson that tied the score in the fifth inning.

The Orioles plunged into the free-agent market before the 1985 season. They signed former Red Sox and Angels star outfielder Fred Lynn as well as veteran infielder-outfielder Lee Lacy. Mike Young took over in left field, and Roenicke, Lowenstein, Larry Sheets, and John Shelby were riding the pine.

On May 21, 1985, Baltimore released Lowenstein, ending his 16-year career in the major leagues. “If it hadn’t been expected, it would be a lot tougher,” he said. “The way the kids were going it was a business decision they had to make and I understand it. It’s kind of been a glorious career for me. I tried not to take anything too seriously, and I hope I have been a positive influence. In a way, it’s a relief.”

Lowenstein did not stray from the baseball diamond for long. He worked as the color analyst for the Orioles, teaming with Mel Proctor on the Home Team Sports Network. After ten years, Lowenstein left the baseball world for good, and he and his wife, Barbara, moved to Las Vegas. She died in November 2005.

The witty Lowenstein was a popular player, and very well received as an analyst. He was a clutch performer on the field, a player who accepted his role for the good of the team. He did not take himself seriously, often displaying a self-deprecating humor that drew people to him. When he was asked years earlier about his plans for retirement, Lowenstein answered, “I am going to be a (players) agent and go to Taiwan and sign up all the Little League champions.”17 Of course, he didn’t.

Sources

Eisenberg, John, From 33d Street to Camden Yards (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2001).

Loverro, Thom, Oriole Magic: The O’s of ’83 (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2004).

Schneider, Russ, More Tales from the Indians Dugout (Champaign Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2005).

http://baltimore.orioles.mlb.com/index.jsp?c_id=bal&tcid=mm_cle_sitelist

http://baseball-almanac.com

http://baseball-reference.com/

http://urbanshocker.wordpress.com/

Cleveland Plain Dealer

Richman, Milton, United Press International, October 4, 1979

The Sporting News

Baseball Digest

Sports Illustrated

John Lowenstein’s file, National Baseball Hall of Fame

Notes

1 Baseball Digest, August 1990 .

2 The Sporting News, October 20, 1979.

3 Milton Richman, United Press International, October 4, 1979.

4 The Sporting News, August 29, 1970.

5 The Sporting News, January 29, 1972.

6 John Lowenstein’s file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

7 Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 30, 1977.

8 The Sporting News, October 18, 1975.

9 The Sporting News, October 18, 1975.

10 Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 30, 1977.

11 Lowenstein’s file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

12 The Sporting News, July 12, 1980.

13 http://urbanshocker.wordpress.com/2007/09/26/john-lowenstein-apathy-club/.

14 Thom Loverro, Oriole Magic: The O’s of ’83 (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2004).

15 Sports Illustrated, July 12, 1982.

16 John Eisenberg, From 33d Street to Camden Yards (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2001).

17 Russell Schneider, More Tales from the Indians Dugout (Champaign Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2005).

Full Name

John Lee Lowenstein

Born

January 27, 1947 at Wolf Point, MT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.