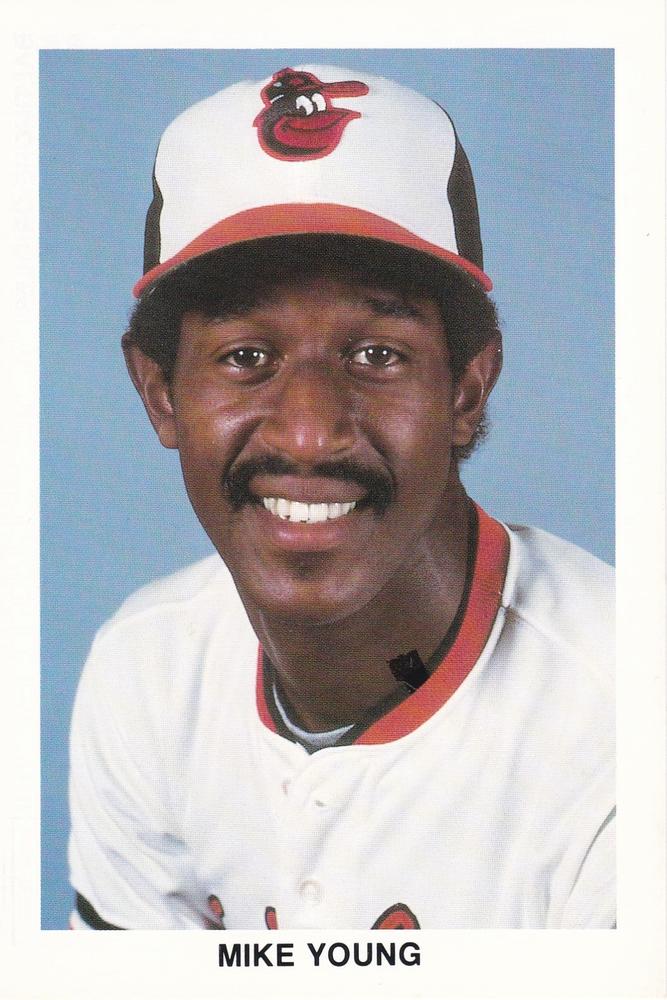

Mike Young

In August 1985, The Cosby Show was tops on television, Back to the Future was a box-office hit, and Mike Young was one of baseball’s hottest hitters. That month, Young went deep nine times in a 14-game stretch for the Baltimore Orioles. He finished the season with 28 homers – 20 of which came after the All-Star break. But the switch-hitting outfielder/DH hit only 27 more round-trippers in subsequent years, and his eight-season (1982-1989) major-league career ended before he turned 30.

In August 1985, The Cosby Show was tops on television, Back to the Future was a box-office hit, and Mike Young was one of baseball’s hottest hitters. That month, Young went deep nine times in a 14-game stretch for the Baltimore Orioles. He finished the season with 28 homers – 20 of which came after the All-Star break. But the switch-hitting outfielder/DH hit only 27 more round-trippers in subsequent years, and his eight-season (1982-1989) major-league career ended before he turned 30.

Michael Darren Young was born on March 20, 1960, in Oakland, California. He was the first of Howard and Mary (Fort) Young’s three children, followed by their daughters Andrea and Valerie. Howard was a probation counselor for Alameda County, while Mary was a keypunch operator for a sand and gravel company. Initially, the family lived north of Oakland in Richmond, but they settled in the East Bay city of Hayward. “It was a close family, a happy family,” Young said. “I have no wild stories to tell. It was a quiet neighborhood.”1

Young was still in diapers when he picked up a plastic bat and started swinging. In due time, his mother bought him a real bat and his first glove. “My mother always said I was born to play baseball,” he recalled. “I always loved to hit the ball. When I was little, I used to hit up against a backstop.” With his grandfather, Young attended San Francisco Giants games at Candlestick Park and rooted for Willie Mays. “I loved his style of play, so aggressive.”2

Initially, Young batted and threw right-handed, but at age 11 he became exclusively a lefty hitter for the next several years.3 That’s how he batted through Little League, Babe Ruth, Connie Mack, American Legion and semipro competition. At Hayward High School, he played one year of basketball, and was a freshman football player as well until his mother convinced him to quit after he was injured.4 In baseball, Young earned All-League recognition three times. As a senior, he was named the Hayward Farmers’ captain.5 He described one high-school highlight on an early-career questionnaire: “Winning our league. In the last game, I went 4-for-4, driving in 8 runs (grand slam).”6 His most memorable hit, though, was a mammoth homer in summer ball. “I hit one that landed in an eagle’s nest in a tree. I was 16.”7

In June 1978, the Cleveland Indians selected Young in the seventh round of the amateur draft, but he didn’t sign. “I just thought I wanted to go to college first,” he explained three years later.8 “I will never, ever forget where I came from… Before baseball, I was simply another guy going to college, trying to get a degree.”9

Young turned down a scholarship offer from the University of Hawaii and attended St. Mary’s College of California, in Moraga, for one year. Then he returned to Hayward and enrolled at Chabot College to pursue a communications degree. Still swinging from the left side, he hit well for the baseball squads at both small schools. But when the Orioles picked him in the first round (11th overall) of the January phase of the draft in 1980, Young recalled, “I was shocked. My scout told me he had been following my career since I was 12… But I had no idea the Orioles were interested in me. I thought the Dodgers or Toronto were going to take me. They had been calling my house.”10 On January 14, 1980, that scout – former Pacific Coast League catcher Caesar Sinibaldi – signed Young for Baltimore.11

“I’ll never forget how scared I was at my first pro camp,” Young said. “I knew I’d be up against players who were as good, if not better, than me. But then I saw that I was good enough to make it.”12 In 1980, Young led the Class A Florida State League with 17 outfield assists, and he was named the Miami Orioles’ hardest worker.13 Miami finished with the worst record in the 10-team circuit, but he paced his teammates in runs scored, doubles, triples and walks while logging an impressive .382 on-base percentage in 115 games.

Next, Young reported to the Florida Instructional League (FIL). After he homered four straight times in batting practice while playfully swinging right-handed, Orioles coach Ralph Rowe asked him to try it in a game.14 “First time up, he hits the ball against the 375-foot sign in left-center,” Rowe recalled. “I knew then that we had a switch hitter.”15

Back at home that winter, Young worked for a television station.16 He returned to Miami to begin the 1981 season, but his league-leading .345 batting average through 63 games earned him a promotion to the Double-A Southern League.17 With the Charlotte (North Carolina) O’s he hit .320 and began showing power in game action – 12 homers in 75 games. “Suddenly, this… switch-hitting outfielder is the new phenom in the organization,” raved the Baltimore Sun in July.18 Young finished the year in the Triple-A International League (IL) by going 1-for-3 in the Rochester (New York) Red Wings’ regular season finale, and 0-for-1 in the playoffs.19 In 139 games overall, Young batted a combined .331 with 15 homers, 35 doubles, 40 stolen bases and 90 runs scored. Reporting from the FIL that fall, Orioles farm director Tom Giordano said, “He’s awesome. He had five doubles in three games and a 500-foot homer.”20

Young was not invited to major-league spring training in 1982, but Baltimore manager Earl Weaver saw him a few times in split- and B-squad games. After Young homered to straightaway center field at Miami Stadium, Weaver proclaimed, “That kid can hit.”21 By going deep eight times in minor-league camp, Young leapfrogged 1977 first-round pick Drungo Hazewood for Rochester’s last starting outfield job.22 In his first full year at Triple A, Young batted .265 with 16 homers. His 11 triples and 82 walks were his highest totals as a professional, as were his league-leading 140 strikeouts. “He’ll have a few games where he’ll strike out, but he seems to bounce back right away and get his hits,” Charlotte manager Mark Wiley had noted the previous year. “And Mike doesn’t get down on himself. He has an excellent attitude.”23

“Mike is a passive, low profile, easy going individual,” Young’s father observed. “He does not like to get into situations where harsh words are spoken. I am that way, and so is his mother to a great extent. If there is shouting, he walks away. If there is someone not headed in a positive direction, he gets away from them.”24

After Young batted .364 (8-for-22) with a homer for Rochester in the 1982 IL playoffs, he was called up by the Orioles.25 He debuted on September 14, in the first game of a doubleheader against the New York Yankees at Memorial Stadium. With Baltimore trailing, 4-3, in the bottom of the eighth, he pinch-ran for Rich Dauer at first base, advanced to third on a hit by Cal Ripken and scored the tying run on Eddie Murray’s single.

The Orioles swept the twin bill to pull within a game and a half of the first-place Milwaukee Brewers with 18 contests remaining. Young appeared in five of them: going 0-for-2, scoring again as a pinch-runner and catching his only chance in left field. Baltimore caught Milwaukee but lost the division in a final day, head-to-head showdown.

The veteran Orioles had no room for Young in their 1983 outfield. “A little patience is all you need, and that’s no problem with me,” he said in spring training. “I like to fish, and nothing takes more patience than that.”26 He returned to Rochester and batted .262 in 65 games before Baltimore called him up when Dan Ford went on the disabled list with a strained knee.27 Young started in left field at Yankee Stadium on June 29 and collected his first major-league hit in the same ballpark the following night – a single batting left-handed against New York’s George Frazier. Batting right-handed on July 15, Young’s two-run triple off the Angels’ Tommy John resulted in his first game-winning RBI.28 During his three-week stay in the majors, Young batted .214 in 15 games (seven starts). “When I first came up here, I was worried, and I put a lot of pressure on myself. But after going through this I’ll come back a more relaxed person,” he vowed.29

Orioles manager Joe Altobelli said, “He has a good arm, he can run, he’s a fine outfielder and he hits with power from both sides of the plate. He’s also very coachable and a super kid. I don’t know how many more tools a kid can have. He’ll be a good big leaguer one day, and I don’t think that day is far off.”30 Back at Rochester, Young batted .326 in 37 games.31 As Baltimore closed in on the AL East title, he rejoined the Orioles in September and went 0-for-8 in 10 appearances off the bench. Baltimore defeated the White Sox in the ALCS, and the Phillies in the World Series, but Young was not on the postseason roster.

That offseason, Young played in the Puerto Rican Winter League for the Cangrejeros de Santurce, managed by Orioles pitching coach Ray Miller. In 50 games, Young hit .322 with 12 homers. He went deep two more times in the playoff semifinals.32 “He’s the talk of winter ball,” Giordano said. “They’re comparing him to Eddie Murray down there.”33

Like Young, Murray – the Orioles’ All-Star first baseman – was a switch-hitting African American from California. Their batting stances, swings, and builds – Young was listed at 6-foot-2, 195 pounds – were also similar. “All of a sudden, everybody started seeing the resemblance, and it was like ‘Well, this guy is trying to hit like Eddie,’” Young said. “But I was not.”34

A poor spring training caused Young to begin 1984 at Rochester, but he performed so well there that Baltimore soon recalled him.35 From May 9 through the end of the season, he appeared in 123 of the Orioles’ 134 games, usually starting in right field. On May 19, he hit his first big-league homer – a game-tying, eighth inning shot off Seattle southpaw Ed Vande Berg. But Young’s batting average was just .229 through the end of July. “I was overly fascinated with just being in the majors,” he acknowledged later. “I had two problems. I was shy and I didn’t want to mess up… I wanted to do too much too soon.”36

Many of Young’s teammates encouraged him, especially Rowe – who had become Baltimore’s hitting coach – and Murray.37 “There were a couple of days when [Murray] talked to me in the beginning, then all of the sudden, we formed that bond,” Young said. “If I had questions about what to expect, Eddie was there, he stressed a number of things to me… He speaks with actions, not words, and that is the way to do it. He is a great role model for any young player.” Young’s father told the Baltimore Sun, “Mike is easy to communicate with and does not have an attitude. Eddie saw those qualities in him and adopted him when he came up.”38

After August 1, Young went deep a team-high 11 times.39 His overall total of 17 homers trailed only Seattle’s Alvin Davis (27) among 1984 American League rookies. Two of Young’s home runs came against the Mariners’ Jim Beattie on August 20. On September 3 at Tiger Stadium, he snapped an eighth-inning tie with his first career grand slam, off Detroit’s Aurelio López. “I think I’ve come a long way and accomplished a lot, considering the slow start,” Young said. “Just the fact that I’m believing I belong here is a big step.”40

That offseason, Young played all 14 games on the Orioles’ goodwill tour of Japan and batted .281. In a brief return to Puerto Rico, he hit .300 with three homers in 50 at-bats for Santurce.41

Young was Baltimore’s Opening Day left fielder in 1985 but started the season in a 3-for-32 slump. The Orioles had added free agents Fred Lynn and Lee Lacy to an already crowded outfield over the winter, and the emergence of rookie slugger Larry Sheets complicated matters. From May 15 through July 2, Young started only seven of Baltimore’s 43 games. With new hitting coach Terry Crowley, he worked on making contact further out in front of home plate to improve his power.42

On July 2 at Memorial Stadium, Young pinch-hit in the eighth inning and struck out against Detroit’s Willie Hernández. When they met again in bottom of the 10th, though, Young pulled an inside fastball from the reigning AL MVP for a walk-off homer.43 Young moved into the lineup in the following series and commenced a career-high 15-game hitting streak. He wound up starting all but three of Baltimore’s last 85 contests. “Mike got a chance, and he took over,” said Weaver, who had come out of retirement to replace Altobelli in June. “He did not let anyone else in there because his performance was such that you did not have to look anyplace else.”44

From July 12 through the end of the season, Young hit 22 home runs – tied for third in the AL in that span behind the Yankees’ Don Mattingly (27) and the Tigers’ Darrell Evans (23). (The Royals’ Steve Balboni also hit 22.) In August, Young went deep nine times in 14 games – including one from each side of the plate against Cleveland on August 13. He earned one AL player of the week award and, with 32 RBIs that month, established an Orioles’ record. The previous mark was 31: by Boog Powell (July 1969) and Doug DeCinces (July 1979).45

In Boston on September 10, the Orioles and Red Sox were tied, 1-1, in the eighth inning until Murray and Young blasted back-to-back homers off southpaw Bruce Hurst. For the first time since he started switch-hitting, Young hit for a higher average right-handed in 1985.46 He compiled 81 RBIs; third among Baltimore players behind future Hall of Famers Murray and Ripken. Overall, he batted .273 with 28 homers in just 450 at-bats. “If he ever gets it all together, he can hit 40 or 50 home runs a season. He is that strong,” said Orioles coach Elrod Hendricks.47

“I like to think that given an opportunity to play a full season, I could continue to produce, but you never know. That may sound modest but I’m trying to be realistic,” Young said. “You have to leave a little room in your mind for disappointment, because of all these people’s expectations.”48

In 1986, Young homered just once in his first 125 at-bats through the end of May. Although his power numbers improved in June, his batting average plummeted, and his strikeouts increased. “[Pitchers] are going to adjust,” Weaver had warned that spring. “When you find the weaknesses, you try to go there. The good ballplayers, the ones who survive, are the ones who adjust.”49

Young’s struggles caused the Orioles to demote him to Triple-A on July 24. “I was trying to eliminate a lot of things in my game this year. Number one was to cut down on my strikeouts. I was thinking of that and still trying to hit the ball hard. I guess I got caught in between,” he said.50 Young performed well at Rochester. He hit two grand slams between August 9 and 15, plus a 500-foot, three-run shot in the ninth inning to beat Toledo.51 He returned to the majors on August 30 and enjoyed a strong September to raise his batting average to .252 in 117 games. But the Orioles finished last for the first time since they moved to Baltimore in 1954, and Young produced just nine homers – the fewest by any AL player who had hit at least 25 the previous year.52

In spring training 1987, Young tore a ligament in his right thumb diving for a ball on March 8. Following surgery and a rehabilitation assignment at Rochester, he made his season debut on May 13. On May 28, he took the Angels’ DeWayne Buice deep to tie a game in the bottom of the 10th, then victimized the same pitcher for a walk-off blast in the 12th. In doing so, Young became just the fifth major-leaguer in history to hit two extra-inning homers in a single contest and the first since Atlanta’s Ralph Garr in 1971.53

Young started all but one game in June and hit well, but the Orioles went 5-23. As manager Cal Ripken Sr. sought a winning combination, Young shuffled between left field and DH, as well as seven different batting order slots. After the All-Star break, he wasn’t in the lineup at all for 18 games. “I love being here. This organization has treated me very well. But I’ve got to play,” Young said that summer.54 “When I look at guys like Eddie Murray and Cal Ripken, they get 600 at-bats. I would love to get that many at-bats and see what I can do. There’s no telling what I could do.”55

In 363 at-bats in 1987, Young batted .240 with 16 homers. “I just never got untracked,” he reflected the following spring. “Last year was the first time I’d been hurt, and it came at a bad time.” Over the offseason, he earned his orange belt in kung fu, ran regularly, and lifted weights. Although he’d previously acknowledged that he would welcome a trade, at the Orioles’ camp in 1988, he said, “I’m not here to stir up trouble… I feel good about myself right now, and I think, if I can stay healthy, everything will fall into place…I’m not taking a trade for granted, and I’m not taking a starting job for granted. I’ve been down here enough to be smarter than that.”56 On March 21, Young was dealt to the Philadelphia Phillies with a player to be named later (outfielder Frank Bellino) for third baseman Rick Schu, and outfielders Jeff Stone and Keith Hughes.

Schu and Stone were in Baltimore’s Opening Day lineup, while Young became chiefly a pinch-hitter in the National League. He started only four times in Philadelphia’s first 49 games, going 5-for-37 (.135) overall, with 12 strikeouts. “Lack of contact,” was Phillies manager Lee Elia’s explanation for Young’s dearth of opportunities. “When you join a ballclub, you have to battle to move someone out of the starting lineup.” On May 20 in San Diego, Elia exploded after Young took a called third strike when he was sent up to pinch-hit in the ninth inning of a tie game with one out and two runners in scoring position. “Swing the bat!” the skipper hollered. “Miracles can happen if you just make contact.”57

“This is the toughest year I’ve had… Things can’t get any worse,” Young said. “I’m not the type of player who makes excuses. I know I need the opportunity to play… If I can’t get the time here, I have to get it somewhere else.”58 Young hit .226 with one homer in 146 at-bats for Philadelphia before he was traded to the Brewers on August 24 for pitcher Alex Madrid. Back in the AL, he appeared in eight contests and went 0-for-14.

Young went to spring training with Milwaukee in 1989, but he was released less than a week before Opening Day, something he called “kind of a raw deal.” He caught on with the Cleveland Indians through GM Hank Peters, who had held the same position in Baltimore during Young’s years there. “I’ve gone through quite a bit of adversity,” Young said when the Indians visited Baltimore. “You’ve just got to keep your head up and keep going. It’s like I blinked and two years went by. But I still have fun playing the game.”59 In 59 at-bats for Cleveland around an 11-week stint in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, Young batted just .186 with one home run.

In 1990, Young signed with the Hiroshima Toyo Carp of the Japan Central League. He homered 11 times in 222 at-bats, but his average was .234. His professional baseball career was over at age 30. In the majors, he batted .247 with 72 homers in 635 games.

Young earned his Associate of Arts degree in Computer Science from Diablo Valley College in Pleasant Hill, California, in 2000. In 2009, he graduated with honors in training and nutrition from the National Personal Training Institute of Ohio. The following year, the Baltimore Sun reported that he operated Genesis Fitness Concepts, and was a partner in the Motivating Our Kids foundation.60 When Young wrote to First Lady Michelle Obama to tell her about his work and offer assistance with her “Let’s Move” campaign, he received an encouraging reply.61 In February 2011, he founded the FLONation Foundation, a non-profit geared to battling obesity.

In 2013, Young married Andreia Hemerly. He already had an adult son, Michael Jr., from a previous relationship. As of 2022, Young and his wife resided in Hayward, where he was a Materials Specialist for Abbott Vascular and remained the FLONation Foundation’s CEO.

Young was 63 when he suffered a fatal heart attack on May 28, 2023, while visiting his in-laws in Atilio Vivacqua, Brazil. His remains were cremated, according to findagrave.com.

Last revised: December 9, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Noes, the author consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retosheet.org.

Notes

1 John Eisenberg, “No Normal Player,” Baltimore Sun, April 6, 1986: 17C.

2 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

3 Greg Boeck, “Mike Young ‘Can’t Miss’ and Can Hit,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), March 23, 1982: 1D.

4 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

5 Mike Young, 1984 Fleer Update baseball card.

6 Mike Young, Publicity questionnaire for William J. Weiss, March 11, 1980.

7 “Three Orioles in Exile,” Baltimore Sun, August 15, 1986: 1F.

8 Ken Nigro, “Birds Start Looking for Cream at Double-A Charlotte,” Baltimore Sun, July 4, 1981: B5.

9 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

10 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

11 Orioles 1984 Media Guide: 191.

12 Ray Parrillo, “Young May Be a Mighty Bird One Day,” Baltimore Sun, February 26, 1983: B1.

13 Orioles 1983 Media Guide: 165.

14 Boeck, “Mike Young ‘Can’t Miss’ and Can Hit.”

15 Parrillo, “Young May Be a Mighty Bird One Day.”

16 Mike Young, 1981 TCMA Miami Orioles baseball card.

17 Orioles 1983 Media Guide: 165.

18 Ken Nigro, “Birds Start Looking for Cream at Double-A Charlotte,” Baltimore Sun, July 4, 1981: B5.

19 Orioles 1983 Media Guide: 165.

20 Greg Boeck, “Jackson’s Looking for a New Team,” Democrat and Chronicle, October 15, 1981: 36.

21 Boeck, “Mike Young ‘Can’t Miss’ and Can Hit”

22 “The 1982 Rochester Red Wings,” Democrat and Chronicle, April 11, 1982: 70.

23 Nigro, “Birds Start Looking for Cream at Double-A Charlotte.”

24 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

25 Orioles 1983 Media Guide: 165.

26 Parrillo, “Young May Be a Mighty Bird One Day,”

27 Orioles 1984 Media Guide: 191.

28 Game-winning RBIs were an official statistic at the time, credited to the player who drove in the run that gave his team a lead that it never relinquished.

29 Ray Parrillo, “It’s Back to Wings for Young,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1983: C2.

30 Parrillo, “It’s Back to Wings for Young.”

31 Orioles 1984 Media Guide: 191.

32 Orioles 1984 Media Guide: 191.

33 “Foul Weather Days in Wings’ Outfield,” Democrat and Chronicle, December 18, 1983: 5E.

34 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

35 Kent Baker, “Young’s Problem: He Was Pressing,” Baltimore Sun, March 22, 1984: D2.

36 Kent Baker, “Young Hits His Stride, Feels He’s Here to Stay,” Baltimore Sun, September 14, 1984: 2C.

37 Richard Justice, “Young Won’t Forget Teammates’ Support,” Baltimore Sun, August 23, 1984: 3B.

38 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

39 Orioles Media Guide ‘85: 190.

40 Baker, “Young Hits His Stride, Feels He’s Here to Stay.”

41 Orioles Media Guide ‘85: 190.

42 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

43 Richard Justice, “Young’s Homer Lifts Orioles Over Tigers,” Baltimore Sun, July 3, 1985: 1G.

44 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

45 Orioles Media Guide ‘86: 209.

46 Orioles Media Guide ‘86: 209.

47 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

48 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

49 Eisenberg, “No Normal Player.”

50 “Three Orioles in Exile,” Baltimore Sun, August 15, 1986: 1F.

51 Orioles 1987 Media Guide: 191.

52 Orioles 1988 Media Guide: 198.

53 Orioles 1988 Media Guide: 198.

54 Kent Baker, “Young Wants Chance to Play Every Day,” Baltimore Sun, July 13, 1987: 3C.

55 Tim Kurkjian, “Young Doesn’t Like to Play DH, and He May Not Have a Spot Here,” Baltimore Sun, August 25, 1987: 3C.

56 Richard Justice, “Mike Young Doesn’t Feel Part of Orioles,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1988: 18.

57 Bill Glauber, “Young Grows Restless on Phillies Bench,” Baltimore Sun, May 26, 1988: 1C.

58 Glauber, “Young Grows Restless on Phillies Bench.”

59 Kent Baker, “Young, Stoddard Return to Scene of Their Good, Old Days,” Baltimore Sun, May 19, 1989: 3C.

60 Roch Kubatko, “Young at Heart,” Baltimore Sun, September 23, 2010, https://www.masnsports.com/school-of-roch/2010/09/young-at-heart.html (last accessed February 11, 2022).

61 “Michael D. Young,” https://www.linkedin.com/in/michael-d-young-83340ab/ (last accessed February 11, 2022).

Full Name

Michael Darren Young

Born

March 20, 1960 at Oakland, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.