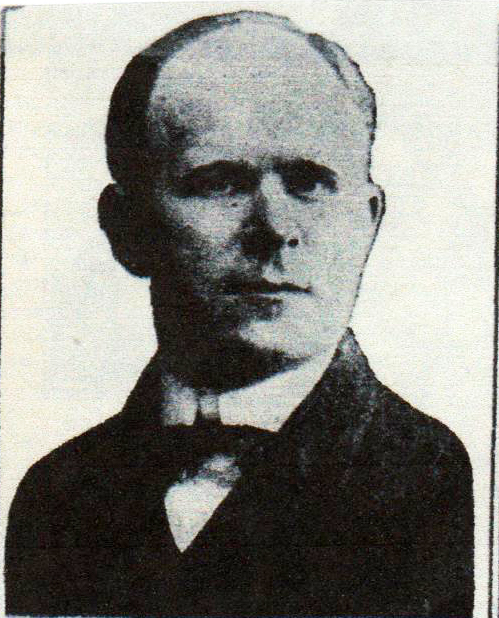

John T. Powers

Like a host of others, the name of John T. Powers was likely as familiar to baseball fans of a century ago as it is unknown to followers of the game today. Throughout the Deadball Era, Powers promoted baseball as a sportswriter, publicist, and organizer of amateur, semipro, and professional nines. His primary contribution to the game, however, proved ephemeral: the founding of the Federal League. Unhappily for Powers, his vision of a circuit growing gradually, cultivating its own playing talent, and avoiding conflict with Organized Baseball was rejected by the impatient businessmen and sports entrepreneurs whom he recruited for FL club ownership. Cast aside as league president in August 1913, Powers watched from the sidelines as the Feds proceeded to wage a costly and ultimately futile two-year battle for parity with the National and American Leagues. Thereafter, Powers returned to less ambitious ventures before fading from the limelight in the early 1920s. His story follows.

Like a host of others, the name of John T. Powers was likely as familiar to baseball fans of a century ago as it is unknown to followers of the game today. Throughout the Deadball Era, Powers promoted baseball as a sportswriter, publicist, and organizer of amateur, semipro, and professional nines. His primary contribution to the game, however, proved ephemeral: the founding of the Federal League. Unhappily for Powers, his vision of a circuit growing gradually, cultivating its own playing talent, and avoiding conflict with Organized Baseball was rejected by the impatient businessmen and sports entrepreneurs whom he recruited for FL club ownership. Cast aside as league president in August 1913, Powers watched from the sidelines as the Feds proceeded to wage a costly and ultimately futile two-year battle for parity with the National and American Leagues. Thereafter, Powers returned to less ambitious ventures before fading from the limelight in the early 1920s. His story follows.

The Early Years

John Thomas Powers was born on June 25, 1874, in Sheffield, Illinois, a railroad whistle stop located about 130 miles southwest of Chicago. He was the fifth of nine children born to coal miner Martin Powers (1839-1903), an Irish Catholic immigrant and Union Army veteran, and his Pennsylvania-native wife Mary Elizabeth (née Dunlevy, 1846-1926), herself the daughter of Irish immigrants.1 Our subject’s early years are shrouded by the passage of time and adult embellishments. But the available historical record suggests that Johnny Powers was educated through high school in or about his birthplace.

Less certain is his introduction to baseball. Like most youngsters, Powers presumably played local sandlot ball. His claims to a professional career, however, are suspect. The oft-repeated assertion that Powers played for pro teams in Fort Worth and Kansas City in the early 1890s,2 for example, is belied by his age and the fact that Powers was then still a high school student in Illinois. Another dubious report had him joining a Fort Worth club in 1894 and finishing out the season with Emporia in the unaffiliated Kansas League.3 Later, he supposedly played for Cripple Creek in the Colorado League.4 No evidence has been found to sustain these claims, or the report that Powers had signed with the Rochester Patriots of the Eastern League when the Spanish-American War was declared in 1898.5 Or that he was “a southpaw catcher playing with Army teams in Cuba.”6

More credible are reports that Power served as a junior naval officer aboard the USS Indiana during the Spanish-American conflict.7 Upon his discharge, he settled in Chicago, where he found work as a reporter covering the local sports scene for the Chicago Times Herald and other publications. Soon, Powers became immersed in his true vocation: the organization of baseball teams and leagues. In time, he became involved in the formation of some 45 ball clubs in the church, industrial, fraternal, and trolley leagues of the Windy City.8 Having earned his spurs in the amateur ranks, Powers deemed himself ready to enter professional baseball. But before he embarked on that career path, he had a domestic matter to attend to: his December 1903 marriage to 22-year-old Chicagoan Mary Purtell. The couple’s union endured for the next 44 years but yielded no children.

Prior to the 1902 season, Powers expressed interest in obtaining a Western Association franchise for South Bend, Indiana, but was frustrated by the league’s shuttering for the year.9 In January 1904, he became a candidate for president of the Central League, an eight-club Class B minor league that included franchises in Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, and West Virginia.10 But unwillingness to uproot himself from Chicago reportedly doomed his chances for the post.11 That fall, friends proposed Powers for leadership of another Midwestern Class B minor league circuit, the Three-I League.12 But nothing ever came of it.

His ambition to lead an established minor league thwarted, Powers decided to seize the initiative and form a minor league of his own. The venue chosen was northern Wisconsin.13 In mid-November, the six-member Class D Wisconsin State League was organized in Oshkosh, with driving force John T. Powers elected league president and secretary.14 Under his direction, the new circuit successfully completed an ambitious 120-game schedule with franchises intact, a matter which a self-satisfied President Powers subsequently attributed to himself and the “staying qualities [sharpened by] the several years’ experience I had in assisting to organize a score or more amateur leagues in Chicago.”15

Powers was re-elected league boss the following January, and the circuit enjoyed a second positive campaign. This time, the singing of Powers’s praises fell to sportswriter F.W. Leahy, who declared that “the success of the effort to maintain professional base ball in Wisconsin for the past two years, and the promising outlook for 1907, are due more to President Powers than any other man in the organization.”16 But others did not look as favorably upon Powers, resenting his dictatorial methods and often-disagreeable personal manner. With officials of the Freeport Pretzels taking the lead, Powers was ousted as WSL president at a league meeting in January 1907.17

Our subject quickly regrouped and spent the spring of 1907 trying to organize a state league in Colorado. At first, his efforts were welcomed by the locals and the contours of a circuit began to take shape.18 But he soon made enemies of powerful figures on the Colorado baseball scene, including Denver ballpark owner John Crabb; potential circuit financier George Morrison Reid, who championed a weekend league over the five-game per week schedule proposed by Powers;19 and influential Denver Post sports editor Otto Floto, who was offended by Powers’s threatening and belligerent reaction to those who expressed views contrary to his own.20 Almost as fast as the Powers balloon had risen in Colorado, it came crashing back to earth.

Undaunted, Powers then set his sights on adjoining Nevada and swiftly organized a four-club circuit. Originally consisting of clubs in Reno, Carson City, Goldfield, and Tonopah, membership in the unrecognized Nevada League fluctuated with the fortunes of the local mining industry. On August 6, 1907, two clubs composed of ball-playing miners met in Goldfield with $5,000 and league bragging rights at stake. To ensure decorum, Powers appointed himself championship game umpire and took the field with a large revolver holstered on each hip. The miners were unimpressed. So was the Goldfield sheriff, who promptly disarmed the gun-toting arbiter. The incident garnered derisive coverage on newspaper sports pages nationwide,21 but Powers remained unfazed. Within weeks, he blithely announced his plans for the Nevada League of 1908.22 His connection to the game in Nevada, however, had come to its end.

He resurfaced in late September 1908, making an unsuccessful bid to wrest the presidency of the Wisconsin State League from his successor, Charles F. Moll.23 For the next few years, Powers worked as a traveling representative for a Kansas coal dealership. He also published a St. Louis trade newspaper, The Coal Journal. But baseball was never far from his mind. And this time, Powers was planning something far grander than a distant state or minor league. His next project was formation of a third major league.

The Stillborn Columbian League of 1912

As 1911 drew to a close, the game seemed ripe for expansion. Over 6.5 million fans had attended a major league game that season. More than 175,000 spectators then crammed their way into the ballpark to see the season-ending World Series, won by the Philadelphia Athletics over the New York Giants in six games. Meanwhile, some 316 teams in 47 Class A to Class D minor leagues had taken the field that year.24

In late December, reports emanating from the Midwest indicated that John T. Powers might be organizing an outlaw baseball league.25 As it turned out, he was, indeed, engaged in such a project, scouring the region for potential franchise locations, suitable ballparks, and financial backers. On January 13, 1912, the new Powers circuit, dubbed the Columbian League and with himself invested as president, was unveiled in Chicago. League clubs were to be installed in Kansas City, Milwaukee, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, and Louisville, with Cleveland, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and several other Midwestern venues proposed for completion of the eight-club circuit.26 The Columbian League professed a wish to avoid war with Organized Baseball, but intended to sign major league players, albeit at a modest wage. Valid player contracts held by National and American League clubs would be respected by the Columbians, but reserve clause claims on players were deemed non-binding. “We are not fighting capital with capital, and do not seek a fight with any person or combination,” declared Powers. But the new league had “the statutory right to exist and compete with the baseball trust” and intended to invoke the federal Sherman Anti-Trust Law if attacked.27

Reaction to the arrival of the Columbian League was restrained. Garry Herrmann, president of the Cincinnati Reds and chairman of the National Commission, Organized Baseball’s three-member governing body, affected nonchalance, stating that establishment moguls had not given “two minutes’ thought” to new competitors. He then added that “these new baseball leagues are started every winter and then blow up as soon as the newspapers have anything else to write about.”28 Other observers were similarly blasé, noting the daunting odds facing those seeking to craft a third major league from scratch.29 Powers then sought to clarify his nascent organization’s aspirations. “The Columbian League is not a third major league, nor will it declare war upon organized baseball,” he said. “We will invade ‘protected’ territories, but we wouldn’t offer fabulous salaries to star players. We want cities represented by home players. There are enough good players in each city to form clubs capable of playing as good ball as the major leaguers.”30

As weeks passed, observers began to take notice that the Columbian League had not announced any ball player signings. Nor had club managers been retained. Development of the new circuit was also handicapped by the arrival on scene of another outlaw, the United States League. Organized by energetic Reading, Pennsylvania, businessman and minor league club owner William A. Witman, the USL was concentrated in New York and other Eastern cities. But it was also a potential Columbian League competitor for patronage and ballpark space in the Midwest.31 Uncertainty reigned as the Columbian League deferred to the USL in Cleveland and Cincinnati and vacillated between being a six-club and eight-club league.32

With the United States League seizing the third league initiative, the prospects of the Columbian League faded. Investor William Niesen, a longtime acquaintance of Powers from the Chicago City League and the owner of a Northside ballpark, transferred allegiance from the Columbian League to the USL.33 But the mortal blow was struck by Otto F. Stifel, the well-heeled brewer who sponsored the flagship Columbian League club in St. Louis and whose financial support was urgently needed to support shakier circuit operations. Stifel decided to withdraw when Opening Day approached without any communication regarding plans, progress, or a schedule received from Powers. Stifel indicated willingness “to toss his hat into the ring for 1913, and will lend assistance and financial aid to a third league, providing some folks of high wisdom take up where John T. Powers left off.”34 For the present, however, Stifel was no longer a backer, and with his departure the Columbian League collapsed. But Organized Baseball had not heard the last of John T. Powers.

The Founding of the Federal League in 1913

Divested of its competitor for third major league status, the United States League took the field for the 1912 season, but reality swiftly set in. With playing talent ranging somewhere between the semipro and Class D minor league level, the outlaw circuit drew poorly at the gate. USL clubs in New York and Washington failed in late May, and a month later the United States League disbanded entirely. After that, the baseball scene reverted to the status quo. Still, neither the USL failure nor the stillbirth of the Columbian League discouraged Powers or dampened his enthusiasm for organizing baseball leagues. But his latest efforts toward that end remained discreet until February 1913, when word leaked out that Powers had lined up backing for a new league to be based in major Midwest cities.35

Divested of its competitor for third major league status, the United States League took the field for the 1912 season, but reality swiftly set in. With playing talent ranging somewhere between the semipro and Class D minor league level, the outlaw circuit drew poorly at the gate. USL clubs in New York and Washington failed in late May, and a month later the United States League disbanded entirely. After that, the baseball scene reverted to the status quo. Still, neither the USL failure nor the stillbirth of the Columbian League discouraged Powers or dampened his enthusiasm for organizing baseball leagues. But his latest efforts toward that end remained discreet until February 1913, when word leaked out that Powers had lined up backing for a new league to be based in major Midwest cities.35

On March 8, 1913, Powers announced the formation of a new six-club baseball circuit to be known as the Federal League.36 The league was incorporated under the laws of Indiana,37 and franchises were granted to backers in Chicago, Cleveland, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, and Covington, Kentucky (directly adjacent to Cincinnati). A 120-game schedule was published, while Powers was elected league president.38 In short order, big names like Cy Young, Bill Phillips, Sam Leever, and Deacon Phillippe were engaged to manage, but no player signings were announced. President Powers stated that the league was “withholding the names of the prominent baseball stars who will be in the fold” until the season opener.39 As it turned out, the Federal League had no more luck than the United States League had had the season before when it came to signing players.40 The on-field talent was no better than lower-tier minor league, at best. But with the exception of the Covington operation, transferred to Kansas City in late June, Federal League clubs completed their schedules. The league’s founder, however, did not survive its inaugural season.

As with the Columbian League, Powers did not claim major league status for the Federal League. Rather, his policy was to avoid conflict with Organized Baseball and build the new league from within over time. But playing as an unaffiliated minor league did not suit the ambitious club owners whom Powers had recruited for the Federal League. Confident, deep-pocketed, and impatient, they were spoiling for a fight with the established big leagues. Then Powers took a perhaps fatal misstep: he rescheduled a Chicago game against Pittsburgh to his hometown of Sheffield, Illinois. Chicago club management, however, swiftly rebuffed Powers, refusing to shift the game to such a small, inconvenient venue.41

On August 3, 1913, the Federal League board of directors deposed Powers as league president, couching the move as the granting of an extended leave of absence to allow him to recover from “overwork” on the circuit’s behalf.42 The explanation was risible, as Powers’s departure was anything but compassionate. As observed by The Sporting News, the league’s founder was ousted “because he is not considered big enough for the ambitious plans that Federal League magnates have laid out for next year.”43 Those plans included declaration of major league status, movement eastward into large metropolitan sites like Brooklyn, Baltimore, and Buffalo, and unrestricted warfare with the National and American League if necessary to obtain marquee-level ballplayers. To achieve their vision to become a bona fide third major league (and not the top-tier minor league that Powers had in mind), the club bosses installed dynamic James A. Gilmore, a coal merchant/ventilating equipment manufacturer and co-owner of the Chicago franchise, as new Federal League president.44

Over the next three years, the swashbuckling Gilmore became the public face of the Federal League in its battles with the game’s establishment. But to his credit, he did not lay false claim to being the circuit’s progenitor. “John T. Powers was the father of the Federal League. I was merely a shareholder of the Chicago club,” said Gilmore, explaining his route to league leadership. “Owing to Mr. Powers’ illness, I was elected president” at the FL board meeting of August 1913.45

The deposed Powers, meanwhile, began formulating plans for a fourth major league, grounded in Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Detroit, cities that had only one club in Organized Baseball.46 “I believe that an eight-club circuit similar to the Federal League could be formed of good towns left out of that organization,” Powers observed. “There is a field for so-called ‘outlaw baseball’ in many places where there is only one national agreement club at present.”47

In advertising his latest initiative, Powers had no shortage of explanations for his unseating as Federal League honcho. At first, he blamed his downfall on “that St. Louis bunch” who opposed Powers’s leadership and endeavored to thwart his plan to eliminate weakling FL franchises, including the St. Louis Terriers.48 Thereafter, he maintained that “it was because I opposed the admission of Baltimore to the league that I was fired as president. I have always argued for a compact circuit. … But when I opposed Baltimore as a member, they kicked me out.”49 Still later, Powers identified magnate opposition to his vision of growing the league slowly with homegrown playing talent and avoiding conflict with Organized Baseball as the root cause for his termination as Federal League president.50 Still, notwithstanding his differences with FL club bosses, the hopes of Powers’ fourth league were largely contingent upon his brainchild’s success. And once the Federal League began showing signs of serious fiscal distress, all prospect of Powers getting yet another wannabe major league off the drawing board vanished. By season’s end, he had settled upon being secretary-treasurer of the Southside Businessmen’s League of Chicago, a recreational outlet which Powers promised would be “run on strictly up-to-date lines and expects to cut a big figure in the amateur game in Chicago.”51

The Final Decades

Soon after the country entered World War I in April 1917, Spanish-American War veteran John T. Powers applied for officer training school, but was overage at 43. A year later, he got close to the action via a more familiar route: recreational director for the YMCA, dispatched to France to create and supervise baseball leagues for off-duty American doughboys.52 Once the conflict was over, Powers expanded his charge to include organizing baseball leagues for discharged soldiers and other Americans studying at French universities.53 He also started La Petite Gironde, a newspaper published in Bordeaux.54 And on his return home in mid-1919, Powers brought a French university all-star baseball team with him and arranged a semipro exhibition game tour of Illinois for the nine.55

Powers remained on the fringes of baseball during the early 1920s, becoming chief umpire for the Chicago Midwest League, a new local amateur circuit.56 He was also appointed head fundraiser for a memorial to be dedicated to recently deceased Chicago baseball icon Cap Anson.57 In the ensuing two decades, Powers drifted away from the game, concentrating his energies on the publication of weekly newspapers for the Englewood and Garfield Park neighborhoods of Chicago and the operation of a family-owned travel agency.58 And he remained active in military veterans’ affairs until near the end of his life.59

Powers returned to his Sheffield birthplace for his final years. His health steadily failed, but his death on December 27, 1947, (likely from a heart attack) was unexpected.60 John Thomas Powers was 73. Following a Requiem Mass said at St. Patrick’s Church, his remains were interred in the nearby parish cemetery. Survivors included his widow, three sisters, and a brother. Powers had no children, and his foremost baseball offspring, the Federal League, had predeceased him by some 32 years.

Acknowledgments

This biography was originally published in the February 2021 issue of The Inside Game, the quarterly newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee.

This version was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

The primary sources for the biographical information provided above include US Census and other Powers family data accessed via Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Minor leagues information was taken from Baseball-Reference and The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2d ed. 1997).

Notes

1 The other Powers children were Elizabeth (born 1867), James (1869), Michael (1871), Frank (1873), Alice (1875), Martin (1879), Agnes (1882), and Mamie (1885). Our subject was not related to such similarly surnamed contemporaries such as Madison Square Garden promotor/Eastern League president/Newark Peppers club president Patrick T. Powers; Pittsburg Press sports editor/Interstate League president Charles B. Powers, or Central League/Pacific Coast League club owner John F. Powers, Jr.

2 As claimed years later in “Powers Busy Preparing His Program,” Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, July 13, 1918: 6; “John T. Powers Goes to France,” San Jose Mercury News, August 3, 1918: 3.

3 According to “For President of Central League,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, January 10, 1904: 6

4 Per “Newspaperman Is After Central Job,” Evansville Courier, January 9, 1904: 5.

5 As maintained in “France Will Witness 1919 Ball Series,” Washington Herald, September 2, 1918: 9.

6 See “John T. Powers, Federal League Organizer, Dies,” (Wilmington, Delaware) Morning News, December 30, 1947: 23.

7 See e.g., “Plans Sport Program,” San Antonio Light, July 22, 1918: 8; “Contest for Trophy,” Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, July 12, 1918: 4. In his later life, Powers organized reunions of fellow Chicago-area Spanish-American War veterans.

8 As subsequently reported in “Ex-Chief of Feds Doing YMCA Work,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 28, 1918: 14.

9 Per “Powers’ League To Start,” St. Paul Globe, March 8, 1902: 6. The “Powers” referred to in the article caption was Western Association President Charles B. Powers, not our subject.

10 As reported in “Newspaperman Is After Central Job,” Evansville Courier, January 9, 1904: 5; “For President of Central League,” Evansville Journal, January 10, 1904: 6.

11 Per “Four More Are After the Job,” Evansville Courier, January 7, 1904: 5.

12 As reported in “Fanning Fancies,” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, October 7, 1904: 2; “J.T. Powers for President of Three-I League,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, October 4, 1904: 9; and elsewhere.

13 See “For a Baseball League,” (Oshkosh, Wisconsin) Northwestern, November 1, 1904: 3; “To Put Green Bay on Baseball Map,” Green Bay (Wisconsin) Gazette, November 3, 1904: 5; “Ball League for North Wisconsin,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, November 7, 1904: 3.

14 Per “Wisconsin League Organized,” South Bend (Indiana) Tribune, November 16, 1904: 3; Rockford Morning Star, November 17, 1904: 6. The new league consisted of clubs based in LaCrosse, Oshkosh, Beloit, Wausau, and Green Bay, Wisconsin, and Freeport, Illinois.

15 J.T. Powers, “Wisconsin State League,” 1906 Spalding Official Base Ball Guide, 279.

16 F.W. Leahy, “Wisconsin State League,” 1907 Spalding Official Base Ball Guide, 275.

17 As subsequently reported in “John T. Powers Was a Walking Arsenal,” Freeport (Illinois) Journal, August 12, 1907: 1.

18 See e.g., “Good News for Fans,” Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, March 9, 1909: 2.

19 See “Reid Withdraws; Powers’ League Is Tottering,” Denver Post, April 10, 1907: 11.

20 See Otto Floto’s Daily Sports Comment,” Denver Post, April 11, 1907: 7, and April 12, 1907: 11.

21 See e.g., “Umpire Carries Two Guns,” Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1907: 6; “Armed Himself to Umpire Game,” Duluth News-Tribune, August 8, 1907: 4; “Umpired Ball Game with Revolvers on Side,” York (Pennsylvania) Gazette, August 14, 1907: 6.

22 See John T. Powers, “Prospects for National Game,” Reno Evening Journal, August 26, 1907: 12.

23 Per “Moll Likely To Be League Leader,” Rockford Morning Star, October 2, 1908: 2; “To Seek Moll’s Place,” Rockford Register-Gazette, September 30, 1908: 5.

24 As calculated from The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2d ed. 1997).

25 See e.g., “Outlaw Ball Maybe,” (Oshkosh) Northwestern, December 30, 1911: 3: “Gary May Have Team in League,” (Hammond, Indiana) Lake County Times, December 29, 1911: 9.

26 As reported in “Another Outlaw Circuit Formed,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 14, 1912: 14; “Outlaw Baseball Movement Grows; John T. Powers Elected President,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, January 14, 1912: 15; “Outlaw Baseball League Gets a Name,” New York Times, January 14, 1912: C3; and elsewhere.

27 See “Big Leagues Face War,” Chicago Daily News, January 19, 1912: 1; “Outlaw League Will Use Sherman Law, Says John T. Powers,” Duluth News-Tribune, January 20, 1912: 11. See also, “New League Will Defy Baseball Law, Says President,” (Covington) Kentucky Post, January 26, 1912: 6.

28 “Herrmann Sarcastic about New Leagues,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 20, 1912: 12; “Major Leagues Calm,” Sporting Life, February 3, 1912: 1.

29 As typified in the dismissive the remarks of Chicago Cubs boss Charles Murphy in “More Backing for Columbian League,” Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald, January 27, 1912: 2. An exception was National League President Thomas J. Lynch whose opposition to any league outside of Organized Baseball was loud and implacable. See “Be Not Too Sanguine!” Sporting Life, March 2, 1912: 5.

30 John T. Powers, “Columbian League Will Invade ‘Protected’ Territories,” Chicago Day Book, January 25, 1912: 24-25. See also, “Inside Dope on Columbian League,” Evansville (Indiana) Press, January 26, 1912: 4.

31 For more on the United States League, see Bill Lamb, “Gotham’s Unknown Nine: The New York Knickerbockers of the United States League,” The Inside Game, Vol XVIII, No. 5, November 2018, 21-28.

32 Compare “Columbian League Cuts Its Circuit to Six Clubs,” Boston Journal, February 19, 1912: 9, and “New League Shrinks,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, February 19, 1912: 1, with “Want an Eight-Club League,” New York Times, February 20, 1912: 9, and “Powers Here; Wants an 8-Club League,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 25, 1912: 25.

33 As reported in “Wray’s Column,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 25, 1912: 12. See also, Clarence E. Lloyd, “Local ‘Outlaws’ About Ready To Throw In Sponge,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 21, 1912: 16

34 Per Sid Keener, “Died of Inaction,” Sporting Life, April 6, 1912: 12, and “Brewer Otto Stifel,” Sporting Life, July 13, 1912: 8.

35 First reported in Michigan newspapers. See “Invasion by Outlaw League Likely To Materialize in 1913,” Calumet News, February 7, 1913: 8; “Columbian League President in Town,” Grand Rapids Press, February 12, 1913: 12; “Columbian League Head in G. Raps,” Kalamazoo Gazette, February 14, 1913: 7.

36 See e.g., “Will Revive League,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 4, 1913: 21; “Federal Baseball League Will Organize with Big Cities on Its Roster,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 9, 1913: 15; “Charter Third League,” Rockford Morning Star, March 9, 1913: 11.

37 Per “Federal League Is Formed in the West,” Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1913: 1; “New Big League Was Organized,” Grand Forks Herald, March 11, 1913: 2.

38 Per Marc Okkonen, The Federal League of 1914-1915: Baseball’s Third Major League (Garrett Park, Maryland: SABR, 1989), 4. The other league officers were M.F. Bramley, Cleveland (vice-president), James A. Ross, Indianapolis (secretary), and John A. George, Indianapolis (treasurer).

39 As reported in “Bill Phillips Will Manage Indianapolis,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 7, 1913: 12; “Federal League Announces Circuit and Playing Days,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 7, 1913: 12; and elsewhere.

40 The United States League also reorganized for the 1913 season, but abandoned play for good after a disastrous opening weekend.

41 As noted by Daniel R. Levitt in The Battle That Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy (Lanham, Maryland: Ivan R. Dee, 2012), 42.

42 As reported in “Fed Directors Give Powers a Long Vacation,” Cleveland Leader, August 4, 1913: 8: “Two Month Rest to Federal Head,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 4, 1913: 7: “Federal League Grants Powers Long Vacation,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 4, 1913: 13; and elsewhere.

43 “This Federal Child Renounces Father,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1913: 1.

44 As reported in “Acting President of Federal League,” Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1913: 8; “Federal League Has New Leader,” Rock Island Argus, August 4, 1913: 4; and elsewhere.

45 See “Men Who Conduct the Federal League,” Springfield (Massachusetts) News, February 2, 1914: 8.

46 Per “John T. Powers Bound To Oppose,” Detroit Times, October 31, 1913: 12.

47 “Powers May Start Outlaw League,” Harrisburg Patriot, January 9, 1914: 12.

48 See John W. Wray, “Deposed Head of Outlaws May Attempt To Retaliate,” El Paso Herald, December 12, 1913: 10.

49 Per “Would Start Fourth League,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 9, 1914: 9, and “Powers Would Lead a Fourth League,” Salt Lake Telegram, January 18, 1914: 37. Powers also complained that he was owed unpaid salary and that the FL had not refunded his $3,000 investment in the league.

50 See “John T. Powers and His Baseball League Are Again on the Job,” Detroit Times, May 20, 1914: 10.

51 Per “Base Ball Briefs,” Washington Evening Star, November 16, 1914: 13. President of the amateur circuit was former major league player and manager Jake Stahl.

52 See “Powers Busy Preparing His Program,” Kalamazoo Gazette, July 13, 1918: 6; “Says Army Sports Are a Big Thing,” Jackson (Michigan) Patriot, July 14, 1918: 19; “John T. Powers Goes to France,” San Jose Mercury News, August 3, 1918: 3.

53 Per “European Baseball Season Inaugurated,” Baltimore Sun, May 6, 1919: 6; “Powers Heads New Ball League,’ El Paso Herald, May 29, 1919: 14.

54 See “Facts for Fans,” Evansville Journal, January 5, 1919: 17.

55 Per “Powers To Bring Ball Team,” Chicago Daily News, May 28, 1919: 2. During its tour, Powers also managed the French team.

56 See “Name Powers Chief Umpire,” Chicago Daily News, June 22, 1921: 17; “Close Decisions,” Rockford Morning Star, June 23, 1921: 7.

57 See “Pop Anson Memorial Slated in Chicago,” Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1922: 10; Woodbury (New Jersey) Times, June 19, 1922: 4.

58 As noted in the Powers obituary published in the Moline (Illinois) Times, December 29, 1947: 17.

59 See e.g., “Officers’ Camp 18th Company To Hold Meeting,” Chicago Daily News, February 24, 1939: 25.

60 See “John Powers, Baseball Promoter, Journalist, Dies at 73 in Sheffield,” Moline Times, December 29, 1947: 17. See also, “John T. Powers, Federal League Organizer, Dies,” (Wilmington) Morning News, December 30, 1947: 23.

Full Name

John Thomas Powers

Born

June 25, 1874 at Sheffield, IL (USA)

Died

December 27, 1947 at Sheffield, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.