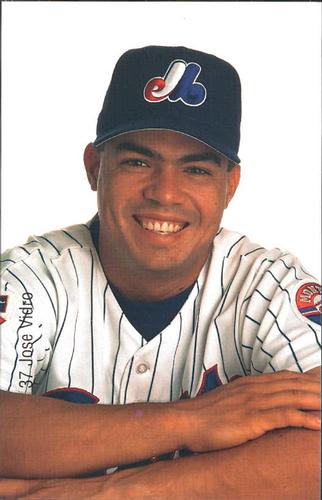

Jose Vidro

The switch-hitting José Vidro made three All-Star teams and batted over.300 for five straight seasons, 1999 through 2003. He remains the best second baseman in the truncated history of the Montreal Expos.

The switch-hitting José Vidro made three All-Star teams and batted over.300 for five straight seasons, 1999 through 2003. He remains the best second baseman in the truncated history of the Montreal Expos.

Born on August 27, 1974, in Mayaguez, on Puerto Rico’s west coast, Vidro grew up about 15 miles away in Sabana Grande, where he played “baseball with tennis balls on makeshift diamonds”1 and attended high school. According to Sports Illustrated, “His father, José Sr., (was) a foreman at a Frito-Lay factory, and his mother, Daysi, was an office worker for Sunkist Foods.”2

Drafted by Montreal in the sixth round of the 1992 amateur draft, Vidro spent six years in the minors, including two full seasons and part of a third with single-A teams. He did attain two major personal milestones during his years in the minors. Vidro married Annette on September 2, 1993. José Vidro Jr. was born on January 7, 1996.

The Expos called Vidro up from Triple-A Ottawa on June 6, 1997, after Vladimir Guerrero was sidelined with a pulled hamstring.3 In his major-league debut, on June 8, he smacked a pinch-hit double off Steve Trachsel of the Chicago Cubs and scored on a single by Mark Grudzielanek. Fourteen hitless at-bats later, Vidro’s second hit was also a double.

Vidro would frequently find his way to the keystone sack after plate appearances and with the glove. He doubled for his first two hits with the Expos, and he would finish in the top three in the National League in doubles in 1999, 2000, and 2002. “The left side [was] his power side, but he [was] not a pull hitter; he spray[ed] the ball from the right-center gap to the left field line. His right-handed hit chart mirror[ed] that pattern — most of his base hits were to center or right.”4

After batting .249 in 67 games for Montreal in 1997, Vidro made the Expos out of spring training in 1998. Montreal needed a second baseman after the offseason trade of Mike Lansing to Colorado. Faced with a glorious opportunity to seize an open position, Vidro began the season by going 0-for-14. Vidro “was sent down to Triple-A in 1998 and watched Vladimir’s brother Wilton Guerrero take over his job”5 in a rare case of a team replacing one 23-year-old switch-hitting second baseman with another. Vidro would return to Montreal and would hit below .200 for every month of the 1998 season save for June, when he hit .325. He finished 1998 with a career-low OPS of .596, a figure that compared poorly with Wilton Guerrero’s .723 mark.

“My second year in the majors was my worst year in my professional career,” Vidro said. “I was trying to do too much and putting too much pressure on myself. … I couldn’t sleep, thinking about what I had to do. Physically I felt perfect, but my mind wasn’t.”6

With his future in Montreal uncertain, Vidro returned home for the offseason. After the 1998 campaign, Vidro “played winter ball … to gain confidence at the plate[; he] did just that by batting .417 in Puerto Rico.”7

Vidro kept his hot bat going and had a breakthrough season at the plate in 1999. “Early talk had him working out in left field, but Rondell White’s move from center to left to protect his knee ended that possibility. Vidro … inherited the second base position … almost by default — Wilton Guerrero wasn’t doing the job,”8 and, unlike the previous year, Vidro started strongly. On April 14 he had the first five-RBI game of his career in a 15-1 rout of the Milwaukee Brewers. On July 18 with one out in the eighth inning, Vidro nearly broke up what would become a perfect game pitched by David Cone of the Yankees, but his smash to the right side was snared by Yankees second baseman Chuck Knoblauch.9

Enough hits got through in 1999 when “Vidro was without a doubt the Expos’ most pleasant surprise … after winning the second base job by mid-May … making significant strides with both his defensive and offensive game.”10 Closing the campaign with an 0-for-27 slump, Vidro finished the season with a still impressive.304 batting average.

After a good 1999 season, Vidro faced unexpected completion going into 2000 when Montreal signed the veteran Mickey Morandini. At a fan festival for the Expos more than a decade after the team left Montreal, Vidro recounted manager Felipe Alou saying that Morandini would play second base. Vidro said he replied, “Good luck with that. He ain’t taking my job. I’m the second baseman here.”11

Indeed, Vidro had a great 2000 campaign. “I’ve always liked him as a hitter,” Jim Beattie, the Expos’ general manager, said. “He reminds me of Edgar Martinez in his knowledge of hitting. Edgar didn’t have a lot of power when he came up, but he developed it at the big league level. José has a chance to hit 20 to 30 homers depending on how hot he gets.”12

Vidro proved Beattie quickly correct by slugging a career-high 24 homers in 2000 to go along with other career highs that year in hits (200), doubles (51), RBIs (97), batting average (.330), and slugging average (.540). He homered for his 200th hit. Ballpark security retrieved the ball and gave it to Vidro, who in turn passed it on to his grandfather, who had attended the game.13

Vidro complemented his offensive production with defensive prowess: “I heard before he got here that José didn’t have the range,” said fielding coach Perry Hill, “but I’ve seen him make plays from shallow right field to behind the bag.”14 Vidro led the NL in assists as a second baseman in 2000 with 442 and made his first All-Star team.

Asked to explain the turnaround after signing Vidro to a four-year, $19 million contract, Beattie said, “It just seems as if he became more serious. This is a guy who, when he first came up, was in a concern group in the three areas we test for: conditioning, strength, and body fat. … He’s worked hard, put himself in better shape and it’s started to pay off.”15

Vidro’s numbers dropped off in 2001 as he missed three weeks with an injury to his left forearm and 11 games after Roy Oswalt beaned him. Vidro expressed frustration that the team’s flinty ownership prevented the franchise from realizing its potential. “They promise a lot and then do nothing,” Vidro said of owner Jeffrey Loria and team president David Samson. “I sat there and watched them talk about how Felipe Alou was going to be our manager all season. … And they fired him two weeks later. We were rabid and hurt. They lied to us.”16

Threatened with contraction after the 2001 season, the Expos rebounded in 2002, when Vidro finally played for a Montreal team that would end a season with a winning record. The Expos scored 735 runs that year and allowed 718 runs — not a notable margin save for the fact that no other team for which Vidro played in the majors had a positive differential. With a .417/.593/1.010 slash line, Vladimir Guerrero was Montreal’s best player, but Vidro, having “shed much of the baby fat and the defensive yips that made him a questionable prospect,”17 also could capably carry the club.

From May 4 through May 27, Vidro had a 21-game hit streak during which he batted .414. With the streak at 18 games on May 25, Vidro led off the bottom of the ninth inning against Philadelphia closer José Mesa. The Expos trailed the Phillies 9-8, and Vidro to that point in the game had gone 0-3 with a walk. Vidro singled off Mesa to keep his streak alive. Troy O’Leary drove in Vidro later in the frame, and the game went to extra innings. In the bottom of the 10th, Vidro faced Hector Mercado and delivered a walk-off grand slam, the second-to-last such hit in Montreal history, to lead the Expos to a 13-9 comeback win that put the Expos just 1½ games out of first place.

May 26 saw another spectacular Vidro performance against Philadelphia pitching. With Montreal down 1-0 in the bottom of the first, he doubled and scored the tying run on an O’Leary single. With the Expos trailing again 2-1 in the third, Vidro doubled but did not score. With Montreal losing, 4-1, in the bottom of the sixth, he singled as the middle man in a three-hit rally that closed the gap to 4-2. By the home half of the seventh, Montreal had fallen behind, 5-2. By the time Vidro came up, Montreal had two on with two out and had narrowed the gap to 5-3. Vidro’s line-drive single made the score 5-4. With Guerrero up and runners on the corners, Vidro broke for second. Vincente Padilla threw a wild pitch that allowed the tying run to score. Vidro advanced two bases on the play, to second on the steal and to third on the wild pitch. Manager Larry Bowa of the Phillies inexplicably had Padilla pitch to Guerrero, and Vlad singled in Vidro with the go-ahead and ultimately winning run as Montreal triumphed, 6-5.

Over parts of two important games given the proximity of the Expos to first place, Vidro in his last seven plate appearances had a walk followed by six straight hits. He had a stolen base, four runs scored, and five RBIs.

On May 27 Vidro kept his hit streak alive one more day by homering in the ninth inning off Tom Glavine, but Montreal fell 5-1 to Atlanta to fall back to .500 at 25-25. The Expos would stay at .500 all the way to 79-79 before winning four meaningless games at the end of the year. Vidro had his best defensive season in 2002: he topped NL second basemen in assists (448), tied with Todd Walker of the Reds for the lead in putouts (314), and finished second in range factor.

After the contraction scare of 2002, the Expos’ escapades would get even more absurd in 2003 when Loria sold the team to Major League Baseball, and Montreal played a score of “home” games in Estadio Hiram Bithorn in San Juan. What would end awfully began beautifully. José’s mother attended the first game there to see her son play in a Montreal uniform for the first time. In his first major-league game on his home island against Graeme Lloyd of the Mets, Vidro hit a two-run homer. “When I was coming around second base, I had tears in my eyes,” he said. “I had thought about what it would be like, to hit a home run in front of my mother, in front of my family. For it to happen … it’s hard to explain.”18

Vidro delivered again in the third game of the eventual four-game sweep of the Mets. Facing Mike Stanton in the bottom of the 10th, Vidro hit a walk-off homer. Rounding the bases, he “punched his fist in the air as chants of ‘Vidro!’ and horns blared”19 in what must have felt like another intensely proud emotional moment for the Puerto Rican native.

The Expos unexpectedly stayed in the playoff hunt for far longer than expected. On August 17 Montreal trailed San Francisco 2-0 heading into the bottom of the ninth. Sidney Ponson had a three-hit shutout with one out when Vidro doubled. Walks to Guerrero and Orlando Cabrera followed to load the bases. Tim Worrell came in for Ponson and struck out Wil Cordero before yielding the last walk-off grand slam in Expos history to Brad Wilkerson as Montreal won, 4-2.

On August 28 a four-game sweep of the Phillies left the Expos, to widespread amazement given the constraints under which the team operated, in a multiple-team tie for the wild card.

But playing home games in two different cities took a physical toll on Vidro and the Expos. “I talk to guys on other teams and they know what we’ve been through,” Vidro said. “They tell me, ‘You guys should really be proud of what you’ve accomplished this season, what you’ve overcome. That makes me feel good. … But for me, it hasn’t been that much fun. … Maybe after it’s over I’ll appreciate it more.”20

The terrible travel wore down Vidro and the Expos, a problem exacerbated by the team’s failure to call up minor-league reinforcements to save a few dollars for the overlords in the commissioner’s office. Vidro’s month-by-month statistics in 2003 show that clear signs of fatigue kicked in after the end of the dog days in August:

OBP SLG OPS

March/April .412 .583 .996

May .413 .438 .850

June .414 .458 .872

July .386 .488 .874

August .404 .438 .841

In September Vidro struggled to a subpar slash line of .318/.379/.697. When asked years later what he would do if he were commissioner, he replied that he would “shorten the season to 150 games.”21 Still, Vidro had put together another fine year overall in 2003, his last All-Star season, setting career highs in walks (69) and OBP (.397).

In 2004 spring training, Vidro expressed cautious optimism going into his contract year, exclaiming, “I just love to be here now and be part of this organization. This is my last year here. We’ll see what happens. … I’m going to be faithful to the team.”22

That positive attitude did not last the summer, as Vidro tired of the travel and tired of the questions about the toll the travel took on the team: “We’ve been trying to deal with it in a way that it doesn’t look too bad, but any way you look at it, it’s really bad. I don’t know what to say anymore. Hopefully, this is the last year of this and we can go on with our business the way the rest of the league does.”23

Montreal and Vidro both regressed in 2004. The Expos stumbled to a 67-95 mark, and Vidro’s batting average dropped below .300 to .294. Like the duration of the Expos in Montreal, Vidro’s 2004 season ended prematurely after he went on the disabled list on August 26 and had “season-ending surgery September 8 to repair recurring patellar tendinitis in his right knee.”24

Vidro showed more faith toward his team than the Expos did to Montreal, which would move to Washington in 2005. Before the move, the Expos broke with precedent and inked Vidro to a contract worth $30 million over four years. Vidro explained, “I didn’t see myself in another uniform. By signing me, it’s a sign we’re going to have a home next year. We don’t have a permanent home, but I feel like in this team I’m in my home.”25

The passing of the Montreal Expos led to the birthing of the Washington Nationals for the 2005 season. Vidro began spring training with healthy knees, but soon hyperextended his right elbow,26 an ominous sign since he later tore a left ankle tendon, which caused him to miss two months. Subsequently, he “battled two strained quadriceps, as well as a bad knee, for much of the second half of the season.”27 Vidro played in just 87 games in 2005 and hit just seven homers.

After a campaign lost largely to his assortment of ailments, Vidro faced competition at second base for the first time since 2000 from a player with far more pop than Morandini, namely, the newly acquired Alfonso Soriano. The Nats wanted Soriano to play left field; Soriano wanted to stay at second. Vidro expressed more interest in another change under consideration in Washington, namely, the construction of a new ballpark to replace the cavernous Robert F. Kennedy Stadium. “I don’t know if I’m going to be here by the time they build the [new] stadium,” Vidro said … “but obviously, it’s a great step.”28

Vidro’s sense of foreboding proved acute, as he no longer played for Washington when Nationals Park opened in 2008. Although he retained his defensive position with Soriano going to left, Vidro again felt frustration with his stadium. Before just the third home game of the 2006 season, Vidro exploded. “He feels RFK Stadium is unfair to hitters. He thinks the club should have moved in the fences during the offseason. … Vidro and [Nationals president Tony] Tavares met … outside the clubhouse … [and] yelled at each other about the issue. …”29

Whether in response to his ballpark or the diminishment of his skills due to repeated injuries, Vidro confessed that he had given up on trying to hit for power: “I have to make some adjustments on hitting just because of the way we play … [a]nd I don’t try to change it when we go [on the road] because it’s not going to work.”30

While healthier than the preceding year, Vidro still missed a month due to a lingering injury that affected his play even after he returned. An observer noted, “His skills appear to have diminished precipitously since his hamstring strain; he has far less range on defense, and he can’t hit for much power.”31 His relatively improved health over 2005 resulted in Vidro posting better numbers nearly across the board in 2006 except in triples, homers, and slugging percentage. His new approach at the plate combined with his leg woes could explain his inability to increase those three numbers.

A premier second baseman for two winning teams in Montreal had become a marginal one for two losing teams in Washington. The Nationals gave up on Vidro, swapping his big contract32 to Seattle for two fringe players, reliever Emiliano Fruto and outfielder Chris Snelling. The Mariners hoped that getting Vidro off the field and using him as a designated hitter would restore the lost luster to his bat. Vidro appeared to agree: “By me becoming DH, it will give me the chance to focus exclusively on my hitting. … I really don’t think my health will be an issue. … It’s going to be very different not being out there in the field all the time.”33

Manager Mike Hargrove looked forward to having Vidro in the Seattle lineup: “José has been a good hitter for a number of years, and cream rises to the top.”34

Playing in just 11 games at first and 10 at second in 2007, Vidro largely served in the DH role, which preserved his health — his 147 games and 625 plate appearances represented his highest totals since 2002 and were the third highest figures in each of these categories in his career. He continued to get on base (.381 OBP), mostly by stroking singles (.314 BA), but his six homers and 59 RBIs represented unacceptably low figures for a DH. Vidro also hit into a career-worst 21 double plays, the seventh-highest total in the AL, further diminishing his offensive impact.

By 2008, Vidro lost his ability to hit singles, the last outstanding aspect of his once stellar offensive game and, perhaps as a corollary, he lost his patience at the plate — he had the lowest walk rate of his career in this, his final season. “I think I’ve swung at a lot of bad pitches,” said Vidro in May 2008.35 Having played second base for the final time in 2007, Vidro became even more of a full-time DH in 2008, playing in only nine games at first. The lack of punch, range, and speed led to Vidro’s release on August 13.

After leaving Seattle, Vidro coached for the Petateros, a Sabana Grande team. He also worked in the Carlos Beltran Baseball Academy, which his son attended. As of 2016 Vidro played in the Puerto Rico Baseball Masters League and lived in Sabana Grande.36 Asked about Sabana Grande, he said, “I love it. I have been there since I retired with my wife, my son and my daughter. I have a … farm and work with other employees. Like three times a year we get hay for sale.”37

José Vidro played his final big-league game on August 4, 2008. His last plate appearance typified his career. Batting against Boof Bonser, a Minnesota righty, Vidro swung lefty and delivered an opposite-field line-drive single to left. Down 6-0 after five innings, the Mariners, thanks to a 10-run sixth-inning rally, topped the Twins 11-6. The win, Seattle’s second straight, improved the team’s record to 43-69, leaving the Mariners in fourth place, 27 games out of first. In the final analysis, Vidro, when healthy, could hit at a high level, but he did so for obscure teams that typically finished far out of playoff contention.

Last revised: August 1, 2018

This biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Notes

1 Barry Svrluga, “Nats’ Vidro Is at Home in the Game,” Washington Post, March 2, 2005.

2 Phil Taylor, “Mystery Man,” Sports Illustrated, June 24, 2002.

3 Expos, Guide 1999, 230.

4 Tom Gatto, “Best Switch Hitters,” The Sporting News, May 26, 2003. Frank Robinson, who managed Vidro in Washington, characterized an opposite-field double as “vintage Vidro.” Eli Saslow, “Vidro Credits Robinson’s Magic Touch,” Washington Post, June 4, 2006.

5 Stephanie Myles, “Vidro Basks in Selection,” The Gazette (Montreal), July 18, 2003.

6 Sean Farrell, “Vidro Becomes New Best-Kept Secret,” Baseball America, July 24-August 8, 2000.

7 Stephanie Myles, “Barrett Handling Duties at Catcher and Third,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1999. Vidro led the league in both batting average and hits with 60. Peter C. Bjarkman, Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005), 259.

8 Stephanie Myles, “The Book on … Jose Vidro,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1999. The subhead of the article listed Vidro as weighing 190 pounds, but Baseball Reference has him at 175, a figure that seems low given that various media guides of the Montreal Expos list him at three higher weights (185, 190, and 195).

9 Buster Olney, “Cone Remains Perfect Mystery to the Young Expos; Montreal Sensed a Historic Day in the Making,” New York Times, July 19, 1999.

10 Expos, Guide 2000, 234.

11 youtube.com/watch?time_continue=488&v=dNst9_cH2To (accessed November 11, 2016).

12 Murray Chass, “Martinez’s Spirit Is Very Special, Too,” New York Times, May 28, 2000.

13 Expos, Guide 2002, 245.

14 “Good Hit, Good Field,” Sports Illustrated, June 5, 2000. “Vidro’s defense has improved every year under the tutelage of first base coach Perry Hill to the point where he can now be considered excellent.” Stephanie Myles, “Cabrera Continues to Thrive at the Plate and in the Field,” The Sporting News, May 28, 2001.

15 Jeff Blair, “Vidro Pushes Hard, Gets Contract Done,” The Globe and Mail, January 18, 2001.

16 Gordon Edes, “Boss Just Doing His Job; Dolan’s Sharp Criticism of Steinbrenner Not Warranted,” Boston Globe, July 21, 2002.

17 Jonah Keri, Up, Up, & Away (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014), 369.

18 Steve Fainaru, “Expos Triumph in Puerto Rico,” Washington Post, April 12, 2003.

19 Rafael Hermoso, “Benitez Shows Way to Another Defeat,” New York Times, April 14, 2003.

20 Charlie Nobles, “For the Expos, It’s All a Wild Card,” New York Times, September 1, 2003.

21 “The Questions With Jose Vidro,” Sports Illustrated, September 3, 2007.

22 Murray Chass, “Simple Twist of Fate Changed Torborg’s Life, and It Helped Save the Life of a Little Boy,” New York Times, March 7, 2004.

23 Jack Curry, “A 28-Day Trip Is Ending for Montreal’s Vagabonds,” New York Times, July 22, 2004.

24 “Rangers Get Park Back to Help for Stretch Run,” Boston Globe, August 26, 2004.

25 Hal Bodley, “Expos’ New Home Plans Will Feature All-Star Vidro,” USA Today, May 18, 2004.

26 Barry Svrluga, “Comeback Kid: Vidro Returns,” Washington Post, March 20, 2005.

27 Barry Svrluga, “Injuries Leave Vidro Waiting for the End,” Washington Post, September 26, 2005.

28 Barry Svrluga, “Vidro, Like Nationals, Is Looking to Keep His Place,” Washington Post, March 7, 2006.

29 Barry Svrluga, “Vidro, Tavares Argue About Dimensions at RFK Stadium,” Washington Post, April 14, 2006.

30 Barry Svrluga, “For Vidro, Doubles Give Way to Singles,” Washington Post, June 2, 2006.

31 Barry Svrluga, “Vidro Gets the Green Light,” Washington Post, September 7, 2006.

32 “Seattle has agreed to pay $12 million of the remaining $16 million on Vidro’s contract for 2007 and 2008. According to a source outside the Washington organization with knowledge of the deal, the Nationals will pay $1.5 million in 2007 and $2.5 million in 2008.” Barry Svrluga, “Nats Agree to Trade Vidro to the Mariners,” Washington Post, December 14, 2006.

33 Geoff Baker, “M’s Deal for Nationals’ Vidro,” Seattle Times, December 14, 2006.

34 Geoff Baker, “Newcomer Vidro in for Tough Adjustment,” Seattle Times, February 20, 2007.

35 Geoff Baker, “Mariners’ Jose Vidro Unruffled by Potential for Less Playing Time,” Seattle Times, May 2, 2008.

36 Thanks to SABR member Edwin Fernandez for the information in the first two sentences of this paragraph, which comes from an email he sent the author on November 17, 2016.

37 Carlos Rosa Rosa, “Jose Vidro Returns to Baseball to Teach,” El Nuevo Dia, November 19, 2016. Thanks to SABR member Angel Colon for sending this article from a Puerto Rican newspaper. I used Google Translator to render the article in English.

Full Name

Jose Angel Vidro Cetty

Born

August 27, 1974 at Mayaguez, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.