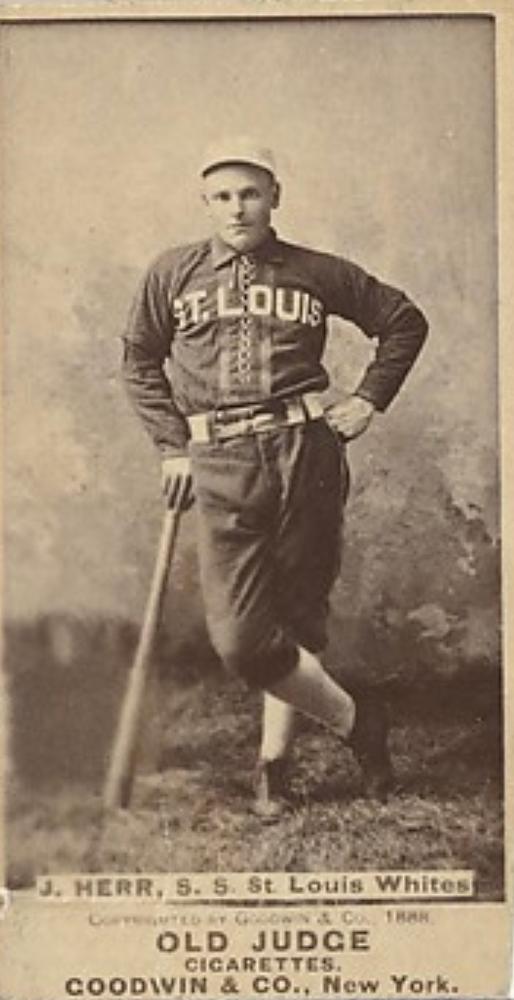

Joseph Herr

Joe Herr was a power-hitting shortstop in St. Louis in 1888, first for the minor league St. Louis Whites of the Western Association, and then for the St. Louis Browns in the major league American Association. Between the two clubs that year he hit seven home runs, three of which went over the left field fence and onto Spring Avenue outside the park.1 The previous year, Herr had hit 13 home runs for Lincoln (Nebraska) in the Western League. His power, like his career, was short-lived. He hit just two more home runs over the next two seasons, and his professional career ended after the 1890 season at the age of 25. However, in death he achieved a feat that probably no other major leaguer has matched: Joe Herr is “The Man Who Died Twice.”2

Joe Herr was a power-hitting shortstop in St. Louis in 1888, first for the minor league St. Louis Whites of the Western Association, and then for the St. Louis Browns in the major league American Association. Between the two clubs that year he hit seven home runs, three of which went over the left field fence and onto Spring Avenue outside the park.1 The previous year, Herr had hit 13 home runs for Lincoln (Nebraska) in the Western League. His power, like his career, was short-lived. He hit just two more home runs over the next two seasons, and his professional career ended after the 1890 season at the age of 25. However, in death he achieved a feat that probably no other major leaguer has matched: Joe Herr is “The Man Who Died Twice.”2

Joseph Herr was born on March 4, 1865, in St. Louis, Missouri, and grew up in the neighborhood where Henry Lucas built Union Base Ball Park for the St. Louis Maroons in 1884. He was the youngest child of George Washington Herr (1819-1893) and Elizabeth (Reed) Herr (1821-1890), both of whom were born in Maryland. His great-grandfather, Johan Peter Neff Herr (1757-1845), came from the Hessian region of Germany around the time of the Revolutionary War.3 His mother’s family may have been part French.4

By the time Joe was born, his family was native-born American. He was the youngest of nine children, with siblings born in Ohio, Kentucky, and Missouri. His father was a carpenter by trade, and young Joe Herr shared that trade with his father as he turned 18 in 1883. He was also playing baseball in St. Louis’s thriving baseball scene. Herr played third base for the East St. Louis Nationals in 1884, and then third and shortstop with the Belleville, Illinois, Baseball Club in 1885.5 Silver King recalled playing with Herr on the Peach Pies, a top amateur club in St. Louis, along with other future major leaguers such as Percy Werden, Pat Tebeau, and Jumbo Harting.6

In 1886, the St. Joseph (MO) club in the Western League signed Herr to play third base. He was considered a strong hitter, with a catch. “Herr has a powerful swing on his body in striking at a ball. If he ever hits it, it ought to go over the fence.”7 During the season, Herr was involved in an unusual incident in St. Joseph — he was beaten by a streetcar driver.8 A group of players were going out in St. Joseph one evening, and they had to run after a streetcar that failed to stop for them.

“Herr mounted the car and as he did so asked the driver why he did not stop. The driver replied: ‘It’s none of your business.’ Herr answered that he did not like to be treated that way. The driver answered, ‘I’ll fix you,’ and at the same time raised an iron bar known as a ‘frog’ and struck at Herr… bruised his wrist and laid his scalp open to the bone for some six or eight inches.”

The driver was arrested and charged with assault with intent to kill. The motive was racial. “Herr is tanned very dark from steady exposure in the sun and the driver says he is very sorry the thing occurred but supposed Herr was a ‘n*****’.” Just a few days later, Herr was back in the game. “The News is inclined to the belief that that thump on the head had a stimulating effect on old man Herr. He played a beautiful game at third and slugged the ball with terrific effect.”9

There are no official stats for the club from that season, but the Leavenworth (Kansas) Times reported “in 48 games at third base [he] had averages of .298 as a batsman and .877 as a fielder, making sixty hits and forty-four runs.”10 St. Joseph finished second in the league with a record of 50-30 behind Denver, which finished at 54-26. Denver and St. Joseph were the only clubs to finish above .500, as Leadville (Colorado) finished in third place at 39-41.11

Despite reports immediately after the season that Herr had re-signed with St. Joseph, he instead signed with Syracuse of the International League for the 1887 season. Syracuse sold him to Cleveland in the American Association in January 1887 for $800. 12

Herr made his major-league debut at third base for the Cleveland Blues on Opening Day April 16 against Cincinnati. In the second inning he walked, then was thrown out at second base trying to advance on a foul fly ball by Cub Strickler caught by catcher Kid Baldwin. In the fourth inning he singled, driving in Myron Allen with Cleveland’s first run of the season. His error in the ninth inning contributed to the final four runs by Cincinnati in a 16-6 blowout of the Blues. Herr is credited as having two hits in four at bats in the box score, but as walks were counted as hits in 1887, one of those was probably his second inning walk. He also had two putouts and two assists with the one error. Playing center field for Cincinnati was George Tebeau, a fellow St. Louis native whose brother Patsy was Herr’s teammate in St. Joseph and on other clubs.13

The Blues were aptly named. After losing on Opening Day, they went on to lose 91 more games, finishing last with a record of 39-92. Herr was not around for the ending. After roughly one month, he asked to be released, despite playing in 11 of the 17 games the team had played to date and hitting .273, with 12 hits and six walks in 50 plate appearances, but only two extra-base hits (both doubles). After his release, he returned to familiar grounds, signing with Lincoln, which finished second in the Western League. Herr hit .384 with 13 doubles, 16 triples, and 13 home runs. The Lincoln club folded on September 27, having lost money all season.14

The 1888 season was the high point of Herr’s career at age 23. He and Lincoln teammates Tom Dolan and Jake Beckley signed with the St. Louis Whites in November of 1887. The Whites had been formed to play in the new Western Association by Chris Von der Ahe, who owned the club along with manager Tom Loftus and Browns star Charlie Comiskey.15 Herr started all but one of the Whites’ first 30 games at shortstop and was the second-best hitter on the club, behind Beckley. He even pitched six innings in relief on May 13 after the starter, Fred Nyce, hurt his hand on a grounder. An injury to Chippy McGarr, the Browns’ regular second baseman, brought Herr to the Browns in early June, where he became the starting shortstop, with Yank Robinson moving to second base. While his hitting continued to be strong, there were comments about his fielding. The Post-Dispatch reported, “The only failing Joe Herr has is timidity in throwing. If he would let the ball go on a dead line to Comiskey as hard as he can throw it, the champion’s captain would take it in just as easily as when Herr ‘lobes’ the ball across the field.”16

In early July, the Browns signed Bill White and Herr was relegated to playing as a substitute in the outfield. On July 24, the Post-Dispatch reported that “Joe Herr says he wants to get away from St. Louis. It is said that he and Von der Ahe had a scene before the boss President left town. Herr will probably be kept, however.”17 On July 26, it was reported that Von der Ahe offered $1,500 and Herr to Louisville for Toad Ramsey.18 Louisville did not take the deal, and it wasn’t until almost a year later that Ramsey was traded to the Browns. At the same time the Buffalo Morning Express reported:

“Joe Herr has offered $500 for his release, but his offer was refused. In 29 games he has a batting average of .271, which is greater than that of Comiskey, Jocko] Milligan or McGarr. While playing at his best, it is alleged that Comiskey, Arlie] Latham, and Robinson began to ‘freeze him out,’ and he could do nothing to please them. Then White was signed at Comiskey’s request, and Herr found himself on the shelf.”19

Herr remained with the Browns the rest of the season, playing just 14 more game (43 games total). He finished with a .267 average with seven doubles, one triple, and three home runs and 43 RBIs. The Browns won their fourth consecutive American Association championship in 1888. After the season, they played a ten-game series against the National League champion New York Giants for the world championship. Herr did not play until late in the series. He managed only two hits in eleven at bats as the Browns lost the series, 4-6. Herr was released by the Browns along with Harry Lyons and Bill White in January 1889 and signed with Milwaukee of the Western Association. However, the Browns almost immediately retracted the release, and it took until March for a deal to be finalized, Milwaukee paying $500 for him. When Herr arrived in Milwaukee, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported, “The Milwaukees have secured a good man in Herr, and he will probably be played in center field. He can play either the in or out field, is a hard hitter and an excellent base runner.”20

In early May, Milwaukee signed Billy Hassamaer to play center field. Gus Alberts was the regular third baseman, and manager Ezra Sutton played second base. By early June, Herr was causing trouble:

“It is not improbable that Joe Herr may be retired to a place on the bench indefinitely, or at least until he plays better ball than he is doing at present. His failure to play good ball, however, is not the only reason for retiring Herr for a while. Ever since the club came home it has been apparent that there was dissension within the ranks. A statement to this effect made some time ago in The Sentinel was vigorously denied, but now it has become so apparent that it can be no longer covered over, and it seems that Herr is to a large extent the disturbing element… The trouble seems to lie in the fact that Herr wants to play in the infield and the manager of the team does not care to play him there.”21

Within a few weeks of that, Herr was suspended without pay, but it was almost another month before he was released on July 17.22 He had hit only .174 with one home run in 26 games. He signed with Evansville (Indiana) in the Central Interstate League, where he played 40 games before being released in late September. Herr returned home to St. Louis where he resumed working with his father as a stair builder, declaring in January 1890 that he was done with baseball. “Joe Herr declares that he will never play ball again. A very wise resolution, for his last attempt was a veritable failure.”23

Retirement may have been the plan, but he still signed with Waco in the Texas League (along with Hassamaer) the next spring.24 He lasted 38 games with Waco, hitting just .186. After his release, he was signed by Chris Von der Ahe once more on June 13. The Browns were struggling through a rough season, having lost most of their stars to the Players League. Herr was signed to replace Jumbo Davis at third base. The reunion lasted two weeks; he was released June 27. He then signed with Jamestown (New York) in the New York — Pennsylvania League. On July 29, the Kansas City Times reported that he had been blacklisted by the Jamestown club for desertion.25 Herr’s mother died two months later on September 28, 1890; it is possible he left because she was already ill at that time.

After the season ended, Herr again quit baseball and went back to stair building with his father. “They may talk about base-ball being a good thing. A player can earn a big salary, that’s true, but he can spend it just as easily. I’ve got more money saved up now, and I behave myself better, too, since I went to work at my trade — stair building.”26 It appears that he was married in 1891 or 1892 to Johanna B. Geary. They had two children, Joseph Jr. (1892) and Elizabeth (1895).27

On February 6, 1894, Joe Herr was arrested in connection with a dispute during the construction of Union Station in St. Louis.28 According to a newspaper article, Herr was striking with other union carpenters outside the construction site as part of a dispute about working additional hours without additional pay. At the end of the day, Herr was in a group that attacked some of the ‘scabs’ as they left work. Sergeant Williams attempted to arrest Herr. “While the Sergeant was conveying Herr to the patrol-box, he was followed by a small mob of strikers, who threw stones and clubs at him and made loud threats… Sergt. Williams was forced to draw a revolver. He backed up against the side of the building and threatened to shoot the first man that came near him. Officers Murphy and Weigel came to his assistance, and the carpenters prudently withdrew.”

A few years later, in July 1897, Herr was again involved in an incident with the police. This time he was arrested for assaulting his wife, Johanna. They got into an argument over her purchasing “certain pieces of bric-a-brac.” Herr left their home, and returned later in the evening, and “after giving his better half a thorough beating he threw her into the street.” Herr was arrested later that night for the assault. “She prosecuted her liege Friday and Judge Stevenson fixed the cost of his ‘playing’ at $50.”29 Johanna died of septicemia on November 19, 1897, at the age of 23.30

Within a few years, Joe married Marie Fisch. The 1900 Census listed them living in St. Louis with Joseph, Jr., Elizabeth and six-month old Helen (1889). A final daughter, Marie was born in 1905. By 1910, the family was fractured. Daughters Elizabeth, Helen and Marie lived with Joseph and wife Marie, while Joseph Jr. was living with his adopted parents, Ed and Alberta Swingley. Joe and Maria separated around 1924. In 1930, Marie was living with her daughter Marie and son-in-law, and Joe was nowhere to be found.

Joe Herr was described by Bill Carle, Chair of the SABR Biographical Research Committee as “The Man Who Died Twice” owing to a long-time confusion over the date of his death. On July 12, 1933, a body was pulled from the Mississippi River, identified as Joe Herr by a friend. Marie Herr and Joe’s brother William both confirmed the identity. A separate friend, Ed Smith, didn’t think it was him, pointing out that “Herr, who had been amateur baseball player, had big hands and feet. The body had small hands and feet.” On July 14, 1933, the body was buried in St. Matthews Cemetery. On July 15, Smith ran into Joe on the street and told him “Why, you’re supposed to be dead! Dead and buried.” The cops were able to track down Herr a few days later in Fairgrounds Park in St. Louis, and wife, daughter, and son-in-law all confirmed that Joe Herr was in fact still alive. Marie explained the misidentification by noting that they had been separated for nine years, and that she had not seen him in three years. The body pulled from the river was never identified; the gravesite is still identified as Joseph Herr.31

Joseph Herr lived three more years before dying (for real) on August 1, 1936. This time he was cremated. Joseph Herr was The Man Who Died Twice. He has two official death certificates to prove that!

Last updated: January 30, 2021 (ghw)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

US Census data was accessed through Geneology.com and Ancestry.com, and other family information was found at Ancestry.com and FindAGrave.com. Stats and records were collected from Baseball-Reference. Articles cited in this biography were typically accessed through Newspapers.com and/or Geneology.com. St. Louis Street Directories were found through Ancestry.com. Joseph Herr’s biography in David Nemec’s Major League Baseball Profiles: 1871-1900 Volume 1 was also a source for this article, as was an article by Bill Carle in the May/June 2019 SABR Biographical Research Committee Report.

Notes

1 “Browns, 7; Clevelands, 3,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 28, 1888: 8. The other two instances were May 1 and May 23.

2 “The Man Who Died Twice,” by Bill Carle in the May/June 2019 SABR Biographical Research Committee Report.

3 Prince Frederick II of Hesse was uncle to King George III and sent more than 15,000 soldiers to the colonies to fight for England during the Revolutionary War. German troops in the war were commonly referred to as Hessians.

4 There seem to be two entries for Joseph Herr and family in the 1880 Census, both living on Montgomery Street in St. Louis, Missouri. One of them has the correct ages for Joseph and the parents, with father George a carpenter born in Ohio and mother born in Indiana (and maternal grandmother born in France). The other has incorrect ages for both parents, both born in Maryland and father George a carpenter, and a brother, George, who was a fireman. According to St. Louis Street Directories from the 1880s and 1890s, Joe’s brother George was a fireman over the years.

5 “The Leaders in the League,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette-Herald, May 23, 1886: 7.

6 “Silver King of St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 28, 1897: 5. This was probably after the 1886 season.

7 “Diamond Hits,” St. Joseph News-Press, June 10, 1886: 1.

8 “Out on a Foul,” St. Joseph News-Press, July 26, 1886: 1.

9 “Base Ball” St. Joseph News-Press, June 30, 1886: 1.

10 “Base Ball Notes,” Leavenworth (Kansas) Times, January 28, 1887: 4.

11 “The Western League Season Comes To A Close,” St. Joseph Gazette-Herald, September 21, 1886: 4.

12 “Base Ball,” St. Joseph Weekly Gazette, January 27, 1887: 5.

13 Game details from “Opening Game Yesterday,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 17, 1887: 10.

14 “The Act of Dissolution,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Call, September 27, 1887: 1.

15 Von der Ahe put up $5000 for the club, and Loftus and Comiskey contributed $2500 each. “Scraps of Sport,” St. Paul Globe, October 29, 1887: 4.

16 “Grand-Stand Chat,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 27, 1888: 8.

17 “Grand-Stand Chat,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 24, 1888: 8.

18 “News of the Day,” New York Sun, July 26, 1888: 3.

19 “General Chat,” Buffalo Morning Express, July 29, 1888: 8.

20 “Baseball Gossip,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 22, 1889: 3.

21 “Is Much Needed,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 8, 1889: 1.

22 “Pick Ups,” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, July 18, 1889: 7.

23 “Notes,” Louisville Courier Journal, January 29, 1890: 8.

24 “Diamond Dashes,” St. Paul Globe, April 27, 1890: 6.

25 “General Sporting Notes,” Kansas City Times, July 29, 1890: 2.

26 “The Base-Ball World,” Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, December 29, 1890: 7.

27 The identity of the first wife, Johanna, comes from the death certificate of Joseph Jr., as no record of the marriage has been located. Joe Jr. served in World War I and is buried in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

28 “Union Carpenters Cause Trouble,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 7, 1894: 4.

29 “She Bought Bric-A-Brac,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 9, 1897: 5.

30 “Died,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 22, 1897: 5. She was buried in Calvary Cemetery. “Sunday’s and Yesterday’s Burial Permits,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 23, 1897.

31 “Shows Up Alive After Wife Holds Funeral,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 19,1933: 3, and “Husband Found Alive After Wife Identifies and Buries Another Man,” St. Louis Star and Times, July 19, 1933: 2.

Full Name

Joseph Herr

Born

March 4, 1865 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

August 1, 1936 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.