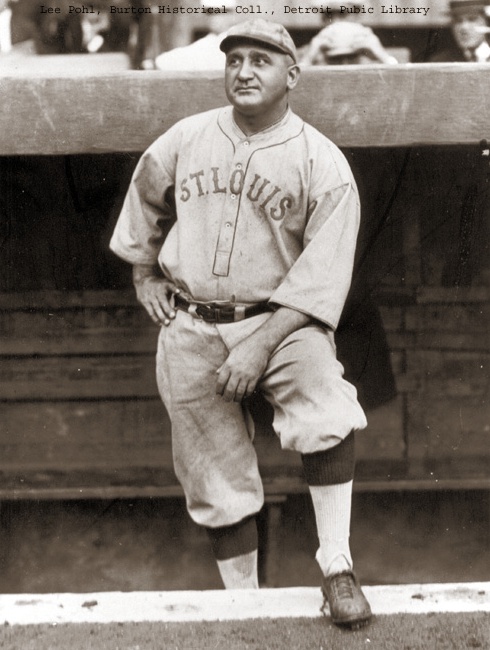

Lee Fohl

Lee Fohl managed 11 seasons in the major leagues in his own unobtrusive manner. “Fohl is unusually quiet. He never seeks the limelight and is inconspicuous in all his acts,” a sportswriter said of him.1 His greatest strength was developing talent. He took the job in Cleveland in 1915 and meticulously built a contending squad. On July 18, 1919, the Indians were in third place battling New York and Chicago for the lead. Fohl’s decision to bring in a seldom used left-hander to face Babe Ruth resulted in a grand slam. The outcry from the fans led Fohl to tender his resignation a short time later.

Leo Alexander Fohl was born on November 28, 1876, near Marietta, Ohio. His parents were John and Mary Ann (Schmitt) Fohl. He had four brothers and a sister. John Fohl worked in a stockyard before moving the family to Barry County, Missouri. They were in Missouri about five years before moving to Pittsburgh when Lee was around 10. Education was not a priority for the family. Lee had a fourth-grade education. His oldest brother, John, was listed in the 1880 census as a farmer at age 10. Fohl did get an education on the baseball diamond and was playing with the best amateurs by the age of 20.

In 1897 Fohl played with the New Kensington team. He saw action in 42 games and batted .380.2 The Warren franchise in the Iron and Oil League made him one of its early roster additions. However, when the season started neither of the catchers listed in the March newspapers was with Warren. The catching chores were handled by a fellow named Mitchell. Fohl played the summer with New Kensington again. In the next few summers, he also played with the Junctions and Pittsburgh Athletic Club.

Fohl was given a look by Fred Clarke and the Pirates on August 29, 1902. He was paired with rookie pitcher Harvey Cushman against the Cubs. Cushman was wild, and the infielders lost their focus. The Cubs scored six runs in the first three innings with only a couple of balls reaching the outfield. In the end, the Cubs won 9-3 on six hits, six errors, and nine walks.3 Fohl made one of the errors and went hitless. He spent the month of September playing for various semipro teams in western Pennsylvania. Clarke liked his potential and arranged for him to play with Des Moines in 1903.

The Des Moines Register introduced Fohl mistakenly to the fans as a new pitcher. The paper correctly reported that he had a good arm and could hit well.4 The Undertakers, who played in the Class A Western League, got off to a slow start and never climbed out of the second division. Their manager was old Joe Quinn, who benefited from Fohl’s strong hitting. His .296 batting average was second on the team to Charley O’Leary’s .311. Fohl’s performance earned him a late-season call-up to Cincinnati.

Fohl debuted for Joe Kelley’s Reds on September 20 when he caught Noodles Hahn against the Phillies. Fohl struggled behind the plate and committed two passed balls, but so did the Phillies’ catcher and there were a combined seven errors in the Phils’ 8-4 victory. Fohl was in the lineup the next day against the Phillies and had two singles and a triple. His fielding was suspect again and the Reds lost 14-13. He made two more regular-season appearances and saw action in a few exhibitions. He closed with a .357 average in four games, but would never shake the evaluation that he was good hitter but weak with the glove. He would not return to the majors until 1915, when he became a coach in Cleveland.

The Reds signed George Schlei and decided that Fohl did not fit their plans. He was placed on waivers and went unclaimed. Milwaukee of the American Association showed interest, but the Detroit Tigers made the most attractive offer. The Tigers hoped to make Fohl a first baseman-catcher, but the plan hit a snag in mid-April. Fohl left the Tigers in a dispute over a $250 advance. Fohl claimed he was owed the money, but the Tigers pointed out that he had not signed a contract.5 Fohl went home to Pittsburgh to play for Homestead, a powerhouse semipro squad. He played over 100 games that summer with Homestead.

Several Eastern League teams had interest in Fohl. The Binghamton Bingoes of the Class B New York State League were also an early suitor and Fohl signed with them. After a month of the season he was falling from favor and jumped the team. He returned to his home and joined the Homestead team, which was playing in the oversized Ohio-Pennsylvania League. Homestead finished under .500, but Fohl starred. He spent most of the season as the cleanup hitter. The league champion Ohio Works team from Youngstown added him to their roster for the exhibition postseason. On October 5 Fohl scored three times on three hits in a 6-5 win over the Cubs. He also saw action against the Phillies and the Baltimore Orioles.

The Ohio-Pennsylvania League downsized to eight teams in 1906. Youngstown won the league title courtesy of a potent offense. The league had only three .300 hitters and Youngstown featured two of them, Bill Thomas at .308 and Mert Whitney at .302. Fohl was ninth in the circuit with a .285 average. After the season Fohl was drafted by Columbus of the American Association, but his selection hit a snag when it was revealed that he had signed a contract without a reserve clause late in the season. Could he be drafted under those circumstances and could Youngstown accept cash for his rights?

Fohl wanted to stay with the Youngstown team and appealed the draft selection. The case dragged on through the winter. Marty Hogan at Youngstown had no desire to return the money and Columbus demanded either the money or the man. Eventually a $150 bonus enticed Fohl to sign with Columbus. Fohl spent two seasons with the Senators. They won the title in 1907 and finished third in 1908.

The Columbus front office had an agreement with the Lima Cigarmakers of the Class D Ohio State League for 1909. Fohl was asked to assume the role of player-manager for the team. He assembled a top-notch squad including some Columbus castoffs, notably Alex Reilly, who led the league in stolen bases. Fohl embraced the running game and on May 28 stole three bases, including third base twice. As a batter he worked counts and often sacrificed, but hit only .225. As a manager he was cool and patient while guiding the team to the pennant. His best work may have been developing 19-year-old pitcher George Kahler into a major-league talent. When the league season ended, Fohl returned to Columbus and played at least four games for the Senators.

Bob Quinn was the secretary of the Columbus club and committed to backing the Akron entry in the Ohio-Pennsylvania League. One of the first moves was to sell Fohl’s contract to Akron and appoint him player-manager. The fans were excited because they felt Quinn “will ship his choicest findings to Akron.”6 The team opened the season against Youngstown. Fohl had two hits and scored twice in a game that went only eight innings because a scoreboard error showed it had gone nine.7 The team dropped eight of the next nine games and stood 2-8 after 10 games. Fohl simply stated that the players needed to gain confidence and play to their talents. He did make a slight change in the batting order. Fohl’s calm demeanor helped weather the storm and from there the Tip Tops went 71-45 to win the pennant.

Akron repeated as champion in 1911. The franchise moved up to the Class B Central League in 1912 and finished under .500, well off the pace. Fohl played 376 games and posted a .298 average with Akron. His performance there was recognized years later, in 1962, when he was inducted into the Summit County Sports Hall of Fame.

Newspapers in January 1913 trumpeted the return of Fohl to Akron. In February negotiations heated up in the sale of the franchise to a group of Akron businessmen. In an odd twist, two purchase prices were discussed, one with Fohl and one without him.8 The businessmen chose the cheaper option, which left Fohl unemployed. He was quickly handed the reins to the newly formed Columbus franchise in the Interstate League.

The Interstate League opened play on May 1 with the Columbus Cubs at Erie. Despite 13 hits, Columbus lost 8-5. The Class D league reorganized in mid-July and then folded late in the month. Fohl left the Cubs and joined the Huntington Blue Sox of the Class D Ohio State League during the reorganization period. His first appearance as player-manager came on July 13 when he struck out three times and made two errors. The loss dropped the Blue Sox to 23-42.9 The team compiled a 45-26 the rest of the way and finished at 68-68.

In 1914, Fohl became player-manager of Waterbury in the Class B Eastern Association. The team had a working agreement with Cleveland and trained in Americus, Georgia, with the parent club. Fohl helped with the pitchers’ camp, held in New Orleans prior to the work in Americus. Guy Morton was assigned to Waterbury so Fohl could tutor him. In the season opener, Morton fanned 14 in a 2-1 win. Fohl kept Morton level-headed when he was courted by the Federal League. In June, Fohl insisted that Cleveland sign Morton to a major-league contract. Meanwhile Fohl was batting third and enjoying his finest season at the plate. On August 4 the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Evening Farmer reported his batting average as .367. He closed out the season at .321 as Waterbury finished second.

Fohl’s work was rewarded with a promotion to Cleveland as coach. His primary responsibility would be to work with the pitching staff. Joe Birmingham was manager. On May 21, with the team in sixth place at 12-16, owner Charles Somers removed Birmingham and installed Fohl. Somers told the press, “I have not given the appointment of a manager a thought, I merely deposed Birmingham. Fohl will manage the team for the present and I will look after the management more myself.”10

Poor Fohl, given the job by default and having the owner on the bench with him. What a way to start a job. Is it any wonder that the words “minor leaguer, busher catcher who never (sic) played as a big leaguer” would dog him the remainder of his career?11The Indians played the Senators in Fohl’s first game and won 7-6 in 12 innings.

The team suffered a 3-14 streak in June and fans lost faith in Fohl and the team. Rival newspapers questioned whether Fohl was serious about winning. Forgotten was the 1914 Naps’ dismal 51-102 mark. Fans feared this season would be even worse. Just as the situation became the gloomiest, the woeful Philadelphia Athletics came to town in July and the Indians swept the five-game series. There was a feeling that the team would improve. Even losing 9 of 10 in September did not dash the long-range optimism. Fohl was given the word on September 22 that he would have the job for 1916.

In 1916 the Tribe went from seventh place to sixth, but they won 20 more games than in 1915. Youngsters like Bill Wambsganss were added, but the big move was the trade for Tris Speaker. Fohl and Speaker worked well as manager and captain. They developed a set of signs to communicate from the bench to center field. The following year the record rose to 88-66. The pitching staff with starters Jim Bagby, Stan Coveleski, and Guy Morton, combined with bullpen ace Fritz Coumbe, were third in ERA and runs allowed. They hurled 19 shutouts.

Fohl did a good job of handling the players, and he was also an innovator. His teams seldom employed the squeeze bunt, which was popular at the time. Fohl preferred to have his batter show the bunt early in the count to bring the fielders in. Then the hitter was to slap the ball past them. Fohl also had a buzzer system rigged up between the bench and the bullpen. When he wanted a pitcher to get ready, he would send a signal.12 But jokesters on the team would ring for warmups when Fohl wasn’t looking.

Because of the World War, the 1918 season ended early with the Indians 2½ games behind the Boston Red Sox. The season closed on September 1 with the team wrapping up an 18-game road trip. Cleveland would have had a very favorable schedule in September and many speculated that the team could have caught Boston. Attendance at League Park was the best for any franchise in the league. Fohl should have been riding high. Instead he was left in limbo and in January 1919 there was still speculation whether he would return. When Tris Speaker was called to the front office, Fohl’s future looked dim.

Team owner James Dunn finally announced on January 4, 1919, that Fohl was retained. “There was never any doubt in my mind as to whom I would appoint manager,” said Dunn. “He has maintained harmony on the team. He knows the game. He has been successful in the development of ballplayers.”.13When asked why he met with Speaker before talking with Fohl, Dunn mentioned that many teams were asking about Braggo Roth and since Speaker had been in the league longer than Fohl, he wanted Spoke’s opinion.

Soon after, Roth was sent to the Athletics for pitcher Elmer Myers, third baseman Larry Gardner, and outfielder Charlie Jamieson. It proved to be a blockbuster trade as Jamieson and Gardner played huge roles in the 1920 pennant race. Myers was used as the fourth starter and a reliever. On July 18 the Indians were hosting Boston sitting in third place. In the eighth inning a pinch-hit triple by Joe Harris but the Tribe up 7-3. Myers entered the game. He got an out before walking Red Shannon. Pitcher Ray Caldwell followed with a double. A grounder scored Shannon. The next two batters walked, bringing Babe Ruth to the plate. Fohl signaled for his left-hander to face the slugger. Coumbe entered the game despite having been on the shelf for seven weeks. On the second pitch, Ruth drove a Coumbe curveball over the right-field fence to give the Red Sox an 8-7 lead. Sad Sam Jones closed out the win for Boston.

Books and articles written in later years mention that Coumbe never played in the majors again. In truth he made one more appearance with Cleveland and then saw action with Cincinnati in 1920-21. Another story that did not appear in contemporary newspapers concerns the communication between Fohl and Speaker in the pitching change. Supposedly Fohl signaled Speaker for his input and Speaker called for a right-hander. Franklin Lewis and others reported that Speaker yelled, “No, No! No, no, not Coumbe”14 when he realized Fohl’s choice. The next day, Fohl resigned, saying, “I feel the fans are not for me.”15Speaker was appointed manager and guided the team to a second-place finish, 3½ games behind Chicago.

Fohl remained with the franchise as a scout for the remainder of the season. In 1920 he managed the Templar Motors team in the City League until a call came from the St. Louis Browns. On June 7 he became pitching coach and scout working with manager Jimmy Burke. Burke was fired after the season. In January, Bob Quinn, the club president, finalized negotiations with Fohl to become the manager.

The team went to spring training in Bogalusa, Louisiana, where Fohl worked diligently with the pitching staff, especially Elam Vangilder and Bill Bayne, and tried to fill holes at second and third. The Browns were fortunate to find Ray Kolp to add to the pitching corps. Earl Smith had been at third, but his fielding was a detriment. He was swapped to Washington for Frank Ellerbe. The hole at second was plugged with Marty McManus, who blossomed under Fohl’s gentle but firm guidance. The team improved its wins total by five and stood poised for a run in 1922.

In 1922 the Browns finished a single game behind the Yankees. George Sisler’s .420 batting average led the offense. The pitching staff had an ERA 0.01 better than the Yankees. Once again pundits and fans selected a pitching decision as the “cause” for the second-place finish. This time it was the unusual use of Hub Pruett during a crucial time in September. Pruett pitched a complete-game victory on September 17. Fohl used in him relief on the 18th and he surrendered the winning run. The team lost the next two and dropped to 3½ games back and could not recover.

Sisler sat out the 1923 season and the pitching staff notably slipped in its performance. The team won only 74 games. Fohl was fired with the record at 52-49. He was reunited with Quinn in 1924 when he was hired to manage the Red Sox. This also reunited Fohl with Steve O’Neill, Wambsganss, and Harris from the Cleveland days. The team won six more games than it had in 1923 and Fohl was rehired.

The Red Sox in 1925 and 1926 won a combined 93 games. Fohl had plenty of pitchers to work with, but his talent for bringing the best out of them never manifested itself. He left Boston with a career 713-792 record. Even that losing record placed him higher than Branch Rickey in lifetime percentage. If only the 1,000-plus games he managed with Cleveland and St. Louis are considered, he had a .528 winning percentage better than the marks of Tommy Lasorda and Dick Williams.

Fohl spent part of the next season in the International League with Toronto. They were the reigning champions, but Fohl was missing four .300 hitters and the best pitcher from that 1926 team. Young Carl Hubbell had also moved on from the team, leaving Fohl with a squad that would finish fourth. He wound up his managerial career with two seasons at Des Moines in the Western League. He left the dugout just as the country was plunged into economic ruin.

Fohl married Pittsburgh native Anna Guehl in 1899. The two were blessed with five daughters and a son. The children were raised in the Cleveland area, which served as home starting in 1914. After his career as a manager in Organized Baseball ended, Fohl scouted and managed sandlot teams. To put food on the table he also managed, and eventually owned, gas stations in Cleveland for nearly two decades. He left the oil business and went to work for the Highland Park golf course for 17 years. He became seriously ill in late September of 1965 and died at the family home in Brooklyn (a Cleveland suburb) on October 30, 1965. Appropriately, Fohl’s funeral Mass was held at St. Leo’s Church and he was buried in Cleveland’s Calvary Cemetery.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 John J. Ward, “Lee Fohl’s Unique Career,” Baseball Magazine, August 1924. On the web at stevesteinberg.net/baseball_history/baseball_personalized/LeeFohl_UniqueCareer.asp.

2 Warren (Pennsylvania) Evening Democrat, March 16, 1898: 4.

3 “Poor Support for Young Men,” Pittsburgh Press, August 30, 1902: 8.

4 “Leo A. Fohl,” Des Moines Register, February 13, 1903: 7.

5 “Fohl Wants Detroit to Pay for the Season,” Detroit Free Press, April 23, 1904: 3.

6 “Bob Quinn Will Back Akronites,” Akron Beacon Journal, February 7, 1910: 8.

7 “Akron Game to Be Protested,” Mansfield (Ohio) News-Journal, May 7, 1910: 9.

8 “Dawson Real Enthusiastic over Interstate Prospects,” East Liverpool (Ohio) Evening Review, February 1, 1913: 9.

9 Chillicothe (Ohio) Gazette, July 15, 1913: 7.

10 Henry P. Edwards, “Cleveland Chief Receives Dismissal From Somers,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 22, 1915: 11.

11 “Somers Says Fohl Remains as Pilot,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 23, 1915: 11.

12 Al Demaree, “Fohl Installed Bell Signals for Warm-Ups,” Rockford (Illinois) Republic, March 23, 1926: 10.

13 Henry P. Edwards, “Cleveland Baseball Magnate Bestows Award to Club Pilot,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 5, 1919: 37.

14 Franklin Lewis, The Cleveland Indians, (New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1940), 100.

15 “Declares Public Is Not With Him; Tris Speaker Manager Rest of Season,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, July 19, 1919: 27

Full Name

Leo Alexander Fohl

Born

November 28, 1876 at Lowell, OH (USA)

Died

October 30, 1965 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.