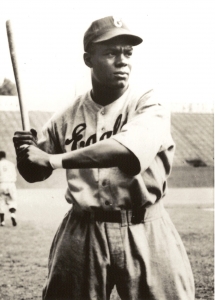

Lennie Pearson

Lennie Pearson was one of the mainstays of the Newark Eagles for more than a decade, but it wasn’t until the 1946 Negro World Series that Pearson came out of the shadows. The first baseman batted an astounding .393 in the Series against the Kansas City Monarchs to help the Eagles put their stamp on their best season.

Lennie Pearson was one of the mainstays of the Newark Eagles for more than a decade, but it wasn’t until the 1946 Negro World Series that Pearson came out of the shadows. The first baseman batted an astounding .393 in the Series against the Kansas City Monarchs to help the Eagles put their stamp on their best season.

Pearson was born Leonard Curtis Pearson on May 23, 1918, in Akron, Ohio. His parents’ names remain unknown, as do those of many African-Americans born in the 1800s. Pearson’s family moved to East Orange, New Jersey, where he starred in football, basketball, and baseball. He and future Eagles teammate Monte Irvin played on the high-school baseball team together. Fittingly, they both became two of the key fixtures on the Negro National League championship Eagles team.

In high school Pearson’s career path was forever altered. While playing football, he injured his arm and thereafter was no longer able to be a pitcher or catcher anymore — something he and Irvin had taken turns doing.1 The arm injury forced Pearson to move to first base, a move that at the time was devastating, but in the long run turned out to be an important break in his career.

In his team rookie questionnaire publicized by the Eagles, Pearson stated, “I would like to express my desires in professional athletics. I hope someday to be chosen to play in the All Star game in Chicago, and stay in baseball at least 15 more year(s). Second is to play professional basketball with some famous team. … My favorite player or the one whom I understudy is George ‘Mule’ Suttles,] especially his hitting and for fielding I understudy Jimmie Crutchfield.”2

In 1937 Pearson dropped out of school and joined the semipro Orange Triangles. He then joined St. Louis of the Negro American League, and later that same year became a member of the Eagles. He batted .211 in 72 known plate appearances that season at age 19. His play picked up in 1938 as he hit .313 in 90 plate appearances for the Eagles. In 1939 he batted .232 in 141 plate appearances, and then surged to .347 in 163 appearances with 42 runs scored in 1940. In 1941 he batted. 273 in 118 plate appearances.3

Pearson spent 12 years in Newark and made six East-West All-Star Games with the Eagles and seven overall. Those East-West games could be pivotal to a player’s salary. In 1941 Pearson made the team with Monte Irvin and Jimmie Hill. Each player’s share from the game was $1,977.76, which was more than half of each of their salaries. Pearson made about $170 per month that season. His salary increased to $300 a month in 1946, after World War II when salaries began to climb again.4 But Pearson was immensely valuable to the Eagles. When teammate Ray Dandridge, a future Hall of Fame third baseman, defected to the Mexican league, Pearson often found himself at third base during the 1939-41 seasons, making the East-West Game in the latter season.

In 1942, he hit .347 in 221 plate appearances with 43 runs scored in the last full season of his first stint with the Eagles. In 1943 he batted .263 in 171 PA’s split between Newark and Philadelphia. He rejoined the Eagles in 1944, batting .266 in 137 PA’s.

Being one of the mainstays in Newark, the 6-foot-2 Pearson was a favorite of Effa Manley, who along with her husband, Abe, owned the team. Effa Manley would become the first woman ever elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. She knew talent and knew how to keep her players happy. According to James A. Riley:

“Pearson, handsome and broad-shouldered, was one of owner Effa Manley’s favorites, and she wanted to keep her paramour close to Newark during the offseason. Taking advantage of the relationship, he frequently borrowed money from the Eagles as an advance on his salary.”5

In fact, Manley cared so much for Pearson that she interceded on his behalf when he was to be drafted into the military in World War II. “Once she did intercede on behalf of a player, when Pearson’s draft board in East Orange called him up at the very end of the war. Besides pointing out that Pearson had previously been classified 4-F, or unacceptable for service because of a bad knee, she went on in her letter to argue that his presence on the club was important ‘because of the big part the baseball team plays in the lives of the Negroes of New Jersey. It is about the only healthy outdoor recreational program they have.’”6

That winter Pearson, who loved playing basketball, chose not to play for the New York Rens basketball team as Manley had arranged and instead went to play winter ball in Puerto Rico. While playing there, Pearson wrote Manley a letter just as the United States entered World War II. “It’s time everyone got in touch with their friends because you never know when you may have the chance again,” he wrote. War in the Pacific “didn’t mean as much but this is a small island and it wouldn’t take too much to sink the whole island” —a reference to German submarines patrolling the US coast. 7

Pearson sent Manley a Christmas card announcing his marriage in 1941, also asking about trade rumors. Effa replied: “I cannot understand why you or anyone else who had been connected with this club would feel that you’re not going to be treated fairly.” They then spoke on the phone and Pearson returned the four-month contract unsigned, saying he expected a five-month contract, threatening to play the season in Mexico instead. “But Manley’s letter to Pearson’s draft board, pointing out that she had advanced him $75 on his salary and that he had signed a contact, evidently dissuaded him. He played for the Eagles in 1942.”8

Manley was helpful in landing Pearson and teammate Leon Day jobs with the Thomas Edison Company in West Orange, New Jersey, even writing them a letter of recommendation. “(Pearson) has always been most cooperative and helpful,” she wrote. “… He is also a real team man. I am sure he will show the same spirit in any field of employment he finds himself in.”9

Again, Pearson’s name came up in the draft during the war, and again Manley went to bat for him. According to Luke, “Pearson received a call from Uncle Sam that would make him the thirteenth Eagle to be drafted. Just before Independence Day, however, Effa wrote a letter to Pearson’s Selective Service Board asking that they delay his induction until the end of the season. She couched her request in terms of Pearson’s value to the team, the ‘big part that baseball plays in the lives of Negroes in New Jersey,’ and the fact that he had previously been declared 4-F owing to a bad knee.”10It worked. He would remain in Newark for the rest of the season.

It worked out in the long run for Pearson and the Eagles. He was a regular .300 hitter. In 1942 he doubled and scored in his only at-bat in the first of two All-Star games played that year. He had one at-bat in the second game and had an RBI. In 1943 Pearson had three at-bats in the East-West Game and went hitless. In 1945 he had one hitless at-bat. In 1946 he went 1-for-3 with an RBI.

Pearson seemed to come up big for the Eagles in the clutch. He hit .308 in 82 plate appearances in 1945, then .320 in 265 PA’s in 1946.

That performance in 1946 was pivotal for the Eagles, who had big goals of winning a championship on a team with a strong blend of veterans and talented young players. The Newark News noted that “infield prospects are exceptionally bright with Pearson, Doby, Isreal and Watkins showing to advantage.”11 Pearson signed his contract for $300 per month.12

After seven games of the season, Pearson was leading the league with a .500 batting average.13 On May 6 he had three hits, including a home run, as the Eagles defeated the Philadelphia Stars 14-6.

He had two hits on June 26 in a 12-8 win over the Homestead Grays to lead the Eagles to their ninth consecutive victory, breaking the club record. They would go on to break that record multiple times that season and during that stretch would win 14 of 15. On July 4 he hit a two-run homer against the New York Black Yankees, the decisive blow in a 3-1 Newark victory.14

Pearson continued his strong play all season. Perhaps his biggest game of the season was played on August 23 when his power hitting helped propel the Eagles to a 10-2 win over the Cuban Stars in the middle of the pennant race. The Newark News headlined the story: “Belting Spree by Pearson; Hits Two Homers and Double for Eagles.” Playing first base, Pearson hit a 400-foot grand slam in the first inning to get the Eagles off to a fast start. “Pearson continued his timely slugging in the second inning when he banged a double to left to tally Monty (sic) Irvin. Again in the eighth Pearson slammed another home run after Monty Irvin had doubled against the centerfield bleachers to bring his runs-batted-in total to seven for the evening.”15

On August 26 Pearson had three hits and three runs scored in a 12-5 win over the Homestead Grays.

On August 30, the Eagles played two games, one against the Grays, the second against the New York Cubans. Pearson hit a grand slam to help beat the Grays, 12-5, then hit another home run against the Cubans for a 10-2 win. “Len Pearson featured the offensive with a four-run homer in the first game and clouted another circuit with Monty [sic] Irvin on in the eighth.”16

Pearson came up big in the clutch, especially in September for the Eagles. On September 3 he doubled, singled, and scored a run as the Eagles swept a doubleheader from the Philadelphia Stars to push a late-season winning streak to 14 games. On September 6 he homered to defeat the New York Black Yankees, 3-2, at Yankee Stadium. He played well at Yankee Stadium. “It was the third home run Pearson has hit in four Stadium games this season. He has made 10 hits in 24 trips to the plate in New York’s big league parks.”17 It moved his season average to .322.

The Negro World Series opened on September 20 in New York. Newark’s Leon Day faced Satchel Paige of the Kansas City Monarchs in one of the most anticipated head-to-head matchups in baseball history. It lived up to its billing with the Monarchs winning, 2-1.

Pearson nearly scored in the second inning. He was walked and Lassies Ruffin, according to one account, “bounced a ball over second which normally would have gone for a hit to score Pearson. However, Kansas City infielders were moving over to cover the runners and Hamilton came up with the ball, touched second and rifled a peg to first for a double play.”18 Pearson came up in the eighth against Paige and grounded into a fielder’s choice. In the next game, he hit a single off Paige, who came in as a relief pitcher in the seventh inning as the Eagles won 7-4.

The Eagles won the title on October 4, 1946, and Pearson, along with Monte Irvin, “made sparkling plays on infield drives in the fourth.”19 He was hitless in the game, but the Eagles held off the Monarchs, 3-2, to win the championship.

After the season Pearson traveled with the Jackie Robinson All-Stars on a barnstorming tour. (He also barnstormed on the Satchel Paige All-Stars against the Bob Feller All-Stars during his career.) He played two more full seasons in Newark, batting .279 in 236 PA’s in 1947 and .294 in 218 PA’s in 1948.

After the 1948 season the Eagles moved to Houston, but Pearson decided to stay closer to home

and joined the Baltimore Elite Giants. He became the player-manager of the Elite Giants, batting a robust .332 and leading Baltimore to the 1949 championship of the Negro American League. It was Pearson’s last year in the Negro Leagues, though his baseball career was not over. During his career in the Negro Leagues, Pearson also played a lot of winter ball. Like many of his teammates and other Negro League stars, he joined the Cuban winter league, finishing with a .262 career average. He also played in Puerto Rico. Pearson had watched several of his teammates help integrate the major leagues, including Newark teammates Larry Doby, Irvin, and Don Newcombe. He made his last appearance in the East-West Game in 1949 as a member of the Baltimore Elite Giants. He went hitless in five at-bats, finishing his East-West career with a .125 batting average in seven games.

In 1950 Pearson joined the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association, his first time playing full-time on an integrated team. He responded by batting .305 for the season. The team finished in sixth place (68-85), 21½ games behind the champion Minneapolis Millers.

Pearson began 1951 in Milwaukee, but later moved to Hartford of the Eastern League. He batted .272. He finished his career with Drummondville of the Quebec Provincial League in 1953, batting .293 with 16 home runs and 58 RBIs. What Pearson did in 1952 is not currently known.

Pearson married Mae Justina Smith, who was born (date unknown) near Athens, Ohio, to parents Robert Lee Smith and Hattie Johnson. Lennie and Mae had a son, Allen Dodd.

After his career, Pearson never strayed far from his home in New Jersey. From 1952 to 1958, he operated the Club 111 Lounge in Newark, and then ran Len Pearson’s Lounge before retiring in 1970.20

Pearson died on December 7, 1980, in East Orange, New Jersey, at age 62. Surviving relatives included his daughter, Valerie; two sisters, Rosa Lee Hunter and Mattie Joy Matthew; and two brothers, Ownsby and Hobie. He is buried in Rosedale Cemetery, in Orange.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted baseball-reference.com. Thanks to the staff at the East Orange Public Library.

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 613.

2 Newark Eagles records, 1935-1946, Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center, Newark Public Library, Box 10.

3 All batting statistics come from Seamheads.com, as of February 2019.

4 Salary information from James Overmyer, Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1998), 121.

5 Riley, 612-613.

6 Overmyer, 180.

7 Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2011), 68, 78.

8 Luke, 82.

9 Luke, 92.

10 Luke, 111.

11 Newark News, April 9, 1946.

12 Newark Eagles official contract to Leonard Pearson, Newark Eagles records, Box 10.

13 New Jersey Afro American, June 8, 1946.

14 Newark News, July 5, 1946.

15 Newark News, August 24, 1946.

16 New Jersey Afro American, August 31, 1946.

17 New Jersey Afro American, September 7, 1946.

18 New Jersey Afro American, September 21, 1946.

19 New Jersey Afro American, October 5, 1946.

20 “Leonard Pearson, Ex-Baseball Star,” Newark Star-Ledger, December 9, 1980.

Full Name

Leonard Curtis Pearson

Born

May 23, 1918 at Akron, OH (US)

Died

December 7, 1980 at East Orange, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.