Murray Watkins

Murray “Skeeter” Watkins was a baseball lifer. He was a Negro League all-star on the left side of the infield in the 1940s for the Cincinnati Clowns, Newark Eagles, and Philadelphia Stars, and when opportunities disappeared he played in the Canadian ManDak League in the early 1950s. He would continue to play baseball for local clubs well into the 1970s.

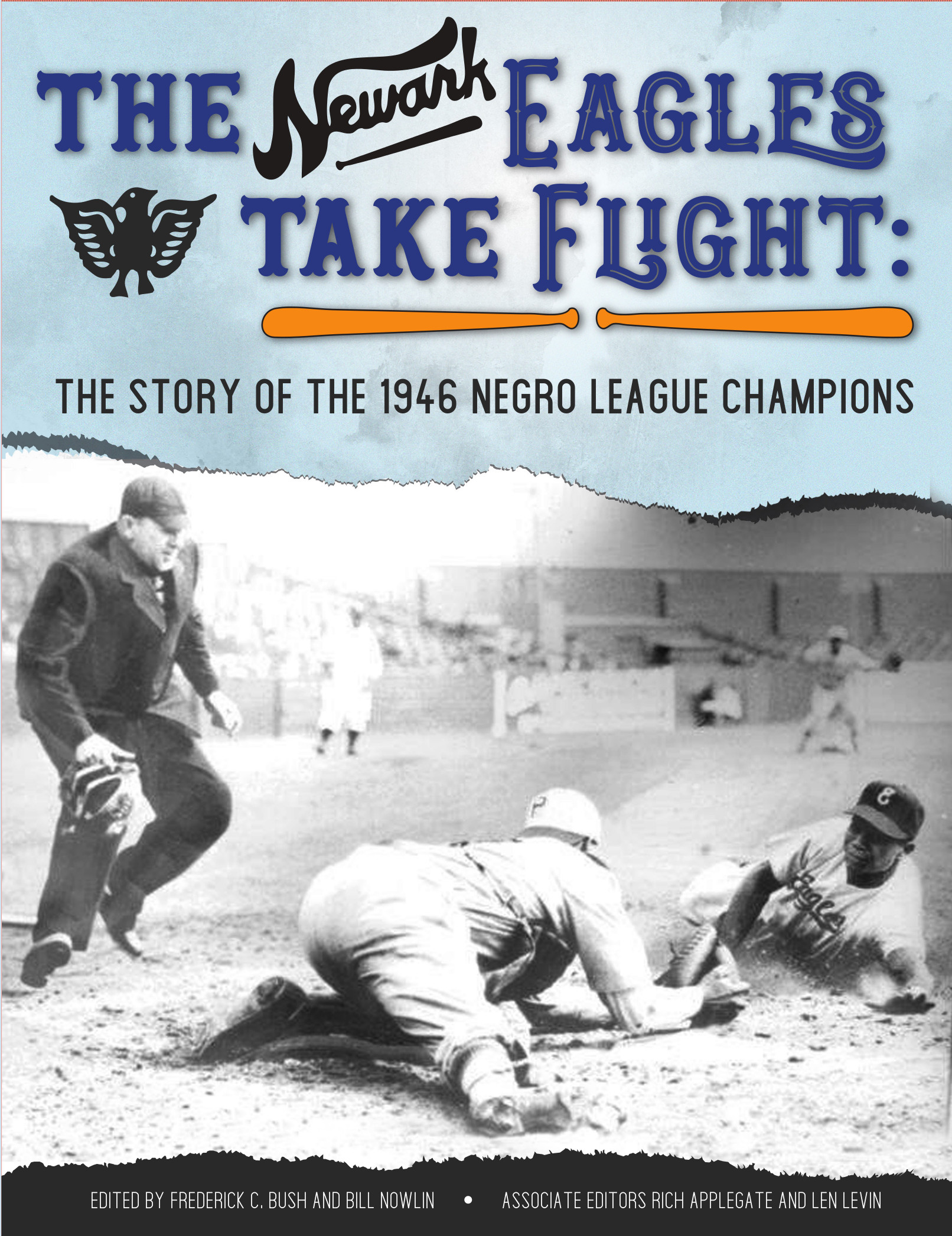

At 5-feet-4, Watkins was a sparkplug at the top of the lineup. He was described as “[a]n eagle-eyed leadoff batter who drew numerous walks (and) combined good speed and extra hustle. … [H]e was a contact hitter with average power. The popular pepperpot was brilliant in the field.”1

On the eve of the first Negro League All-Star Game in 1940, Philadelphia Tribune columnist Ed Harris wrote, “Unheralded and unsung they do their work day by day during the hot summer months … whether we hear about them or not, they exist, (and) as long as they exist, baseball lives on.”2 Baseball existed because of unheralded lifers like Watkins, but he was realistic in his pursuits. “I was just too old when my chance (to play in the white majors) came,” Watkins said years later.3

Maurice Clifton Watkins was born on October 16, 1915, in Towson, Maryland, to Thomas and Mary Watkins.4 When Murray was 14 and playing the outfield, he dove for every ball hit to him,” an article about him said. “I don’t know why, but I had to fall down in order to make the catch.” The article noted that unorthodox style of play led to a future on the infield, as he left the outfield for good in 1937.5

According to James Riley’s Biographical Encyclopedia, Watkins began playing baseball with the Orangeburg Red Sox as a center fielder in 1932 along with two unknown brothers. He later played for Doc Thomas’s Baltimore semipro Colts team.6

Watkins saw his first professional action with the 1941 Philadelphia Stars. Third baseman-shortstop Mahlon Duckett was one of the “freshmen” managers Oscar Charleston relied on.7 Meanwhile, Watkins battled for playing time with infielders Duckett, David Campbell, and Larnie Jordan.8 The Stars “limped” to the end of the season and finished 1941 with a record of 17-52.9

Watkins played for both the Cincinnati Clowns and Newark Eagles in 1942. The Clowns were a huge drawing card and featured the double-play combo of Ray Niel at second and Jim Oliver at short, who executed over 100 double plays in 1941.10 Watkins was working in a steel mill at Sparrow’s Point in Baltimore and chose to barnstorm with the Clowns for two weeks.11 It is likely that the young backup infielder was discovered by the Newark Eagles while on tour with Cincinnati. The Clowns’ nickname mirrored their clown-like antics. But they could play and draw a gate. Eagles owner Effa Manley said, “I didn’t like the Ethiopian Clowns. I wanted baseball to be dignified.” But one day in New York, she saw them “and I don’t think anybody in the park laughed louder than I did. So after that, I stopped complaining.”12

Watkins joined the Eagles in August 1942;13 he was signed for $400 a month.14 Newark featured Ray Dandridge, “the best third baseman in Negro Baseball”15 and one of the “finest infields in Negro baseball” with shortstop Willie Wells and second baseman Pint Israel.16 Watkins, at age 26, played in seven games and batted 3-for-24 (.125) with two RBIs and three walks. It was Wells, one of the “lauded stars (who) have seen their best days,” whom Watkins looked to replace.17

According to Negro Leagues historian Jim Riley, the Eagles’ owners were “diminutive, cigar-chomping Abe Manley, who made his fortune in the New Jersey numbers trade” and Harlem real estate, and his wife, Effa, a “feminist, businesswoman and a revelation (ahead of her time).”18

The Eagles played at Ruppert Stadium, home of the white Newark Bears of the International League. The venue was a “spacious ballpark on Wilson Avenue squeezed between warehouses, factories and rail yards. Billboards advertised Ballantine beer. Jocko Maxwell, one of the first African-American sportscasters, was the Eagles’ public address announcer.19 The Number 31 bus ran down South Orange Avenue and brought fans to the ballpark.20 Although smoke and the smell from a nearby garbage dump were prevalent,21 making for a less pleasant atmosphere when the wind blew in those scents, the Eagles still averaged 3,200 fans per game for 12 dates in 1942 and 2,500 for 11 dates in 1943.22 Noxious odors aside, to black poet and Newark resident LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), the Eagles were “legitimate black heroes” and “extensions of us.”23 According to batboy Ronald Murphy, “black kids, especially those who played baseball, ‘idolized’ the Eagles players.24

In 1943, after a monthlong spring training,25 Watkins played shortstop and batted in the leadoff spot for manager Mule Suttles. According to box scores, Watkins played short and third and Larry Doby manned either second or short in 1943.26 Watkins made $170 a month compared with future Hall of Famer Leon Day, who earned a team-high $300 a month in 1943. Watkins received pay raises to $225 a month in 1944, $250 a month in 1945, and $300 a month in 1946.27

Still regarded as a rookie in 1943, Watkins was considered “the best defensive third baseman in the league, but had only average range.”28 He performed well and became an all-star. Watkins went 1-for-5 as the starting third baseman for the North All-Stars at Griffith Stadium in Washington on September 9. The North was made up of players from the Eagles, New York Cubans, and New York Black Yankees. Marvin Barker of the Black Yankees was the shortstop.

The Eagles finished the 1943 season in the middle of the seven-team Negro National League with a 26-32 record. Watkins hit .230 in 33 games with 22 runs scored and 9 RBIs; the 22 runs ranked third on the team. On defense, he had a .908 fielding percentage at third base and .919 fielding percentage in five games at short.

Despite a light bat, Watkins claimed he got looks from the white major leagues. He told a reporter years later, “I could hit them all and I was a good fielder. At one time both the National and American League had representatives looking at me and talking to me, but by then I was already 29.” With two years of minor-league seasoning, he would have been 31 (in 1946), too old, he thought, except for guys like Paige and Luke Easter.29

In 1944 Watkins hit .188 in 33 games with 18 runs, 3 extra-base hits (all doubles), and 8 RBIs. The Eagles finished the year at 32-35, well ahead of the last-place Black Yankees (8-33) but far behind the first-place Grays (47-24).

Watkins was one of the most popular Eagles in 1945. He received 1,275 votes in a popularity contest, with the two teammates who finished in second place garnering only 300 votes apiece.30 Watkins earned $250 a month for the five-month season plus $20 per week during spring training. On April 19 Effa Manley told him that if she had a good year at the gate and Watkins played well, she’d give him an extra $100.31 Watkins was fortunate to receive such an offer as Manley did not appreciate players asking for more money and “players who tried to wheel and deal during contract negotiations were met with an unbending resolve.” The extra money could come in handy; Manley also expected her players to dress nicely off the field, with their attire including fedoras, long coats, and silk ties.32

According to the Eagles’ publicist at the time, J.L. Kessler, “Watkins is a pint-sized individual with plenty of nerve. He is batting over .300 and gets in front of sizzlers that the average player would wave at and let go as a base hit. Has a steel arm that allows him to throw out speedsters after knocking down the ball down.”33 Watkins hit ninth at the 1945 East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park on July 29 as he and Black Yankees shortstop Willie Wells made up the left side of the infield.34 Watkins was 2-for-2 with a walk in the East’s 9-6 loss. In addition to playing in Negro League baseball’s annual showcase game, Watkins also remembered the first time he faced Satchel Paige – in 1945, the “same day (World War II) ended. He never struck me out but I didn’t get a hit off him. And I remember something else. He broke my bat off in my hand. You don’t know how hard this man could throw.”35 For the 1945 season, Watkins hit .198 with 12 runs and 7 RBIs in 23 games for the third-place Eagles, who ended the campaign at 27-25.

After the season Watkins played for the Negro National League All-Stars in Brooklyn in a five-game series against Charley Dressen’s All-National League All-Stars. The first games, a doubleheader on October 7, were played in front of 12,000 fans. In the nightcap, Watkins could not glove a ball off the bat of the Dodgers’ Eddie Stanky, which allowed the winning run to score in the 2-1 loss.36 After two more losses (10-0 and 4-1) and a 0-0 tie, Effa Manley noted that Watkins suddenly was error-prone, “seemed scared to death. In fact, all of the colored boys did.”37

The 1946 Eagles saw the beginning of the end of the Negro Leagues, as players were scooped up by the white major leagues. Catcher Roy Campanella and pitcher Don Newcombe signed with Branch Rickey‘s Dodgers, and Effa Manley did not forget.38 Upon seeing Rickey at a Black Yankees-Eagles game in July, she made the Dodgers owner “turn purple,” stating, “I hope you’re not going to grab any more of our players. … Our contracts … would stand up better in court than you have in the majors.”39

Nevertheless, the 1946 Eagles assembled one of the top five teams in league history and finished 56-25-3.40 The team featured five future Hall of Famers – Biz Mackey, Leon Day, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and Effa Manley, who helped to put together this formidable squad. The team would, however, be without Watkins before the end of the season.

In June the popular Watkins was traded for Philadelphia Stars third baseman Pat Patterson. In response to Effa’s concerns about trading the popular Watkins, Abe Manley “just laughed and said that the fans would appreciate Patterson quick enough.”41 Effa Manley, who was ridiculed by the fans about the trade, said years later, “I don’t think we would have won the pennant without (Patterson). He was magnificent.”42

With the Stars, Watkins joined second baseman Mahlon Duckett and Frank Austin at shortstop and made a run at the first-half title. The Philadelphia Tribune wrote, “(T)he brilliant surge of the local nine has been attributed to the sparkling play of the new infield combination (which defensively is about the best in the Negro ranks).”43 The Stars finished the first half in second place. Watkins, the “5 foot 4-inch firebrand,” was a reserve for both East-West All-Star Games, on August 15 at Griffith Stadium and August 18 at Comiskey Park. He joined the East, which included a number of his former Eagles teammates, as one of six infielders on the team.44 The Grays’ Howard Easterling started at third for the East. Watkins ran for Josh Gibson in the first game and in the second game was hit by a pitch and scored the only run of a 4-1 loss. For all-star trivia purposes, Watkins, Lloyd “Ducky” Davenport, and Frank “Groundhog” Thompson were the game’s all-time shortest players.45

Philadelphia was unable to keep up with the Eagles in the second half as “the Stars reverted to playing poorly … and failed to challenge the Newark Eagles for the league championship.”46 The Stars finished fourth at 34-36-4. Watkins had his finest season yet as he batted .264 in 154 games with 28 runs and 15 RBIs.

The Stars played at Parkside Field at 44th and Parkside adjacent to the Pennsylvania Railroad roadhouse. The trains generated heavy smoke that showered coal dust on the fans.47 Money and poor play became factors for the Stars as they finished fifth in 1947 and fourth in 1948. The integration of baseball also took a toll on the franchise. The Stars paid upward of $45,000 in ballpark rental and the Negro National League likely lost $100,000 in operating costs.48 “Due to high salaries and dwindling gate receipts, nearly every Negro league team lost money (in 1947),” a local scholar wrote.49 According to catcher Stanley Glenn, most of the travel for the Stars was confined to six cities – New York, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Washington – and much of it was by train. Spring training was held in North Carolina and it was nothing to travel for 500 or 600 miles per day by bus, eat bologna sandwiches, and sleep on the bus or in someone’s private home.50

In December 1947 manager Homer “Goose” Curry was replaced by Oscar Charleston. The 1948 team was old with the 31-year-old and “colorful” Panamanian Frank Austin at short and 32-year-old Watkins at third.51 Four other players were over 35. The team also had financial problems and lost the use of Bolden Bowl; with both the Athletics and Phillies using Shibe Park, there was not space to use the major-league ballpark. The monthly payroll for each Negro League club also was reduced to $6,000.52

The Negro National League disbanded after the 1948 season. The Negro American League added the Stars, Cubans, and Baltimore Elite Giants and drafted players from the other disbanded clubs. The Stars were considered the “dark horse in the race”53 for the 1949 NAL pennant with a revamped and highly touted double-play combo of Bus Clarkson and Marv Williams.54 Watkins remained at third. Struggles continued for the club. After Williams jumped to Venezuela, the Stars were left with 16 men and struggled for bodies in late July.55 The team also embarked on a three-week road trip through Texas, Alabama, and Louisiana. In July it played at “home” Shibe Park for the first time in two months.56

In spite of the team’s hardships, Watkins finished the 1949 season with a .959 fielding percentage at third base that was second only to Lou Brown’s .975 for Chicago; he made just five errors. (Brown had two.) At the plate, Watkins hit .213 (51-for-240) with 32 runs and 7 RBIs in 62 games.57 The Stars were 28-35, well behind Baltimore’s 63 wins. The Elite Giants won both the first- and second-half Eastern Division crowns.

In October and November 1949, Watkins joined the Jackie Robinson All-Stars with Robinson, Campanella, Doby, Buck Leonard, and Don Newcombe.58 Building off Robinson’s popularity in the South, the All-Stars drew 75,000 in its first nine games; that number included 15,871 at Rickwood Field in Birmingham. A total of 148,561 spectators saw the team in its first 25 games, which far exceeded the 100,000 that its organizers had expected. Louisiana fans pushed through the turnstiles to the tune of 16,000 at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans and 8,000 “jubilant” fans attended at City Park Stadium in Baton Rouge.59

Watkins’ final season in the Negro Leagues included time with the Stars and a brief stint with the Indianapolis Clowns. Philadelphia Tribune columnist Kimmie Debnam noted that Charley White took over at third base for the Stars,60 but the same paper also listed Watkins as one of the players counted on for the Stars two weeks later.61 He was listed in another box score at second base in late May.62 New York Amsterdam News writer Joe Bostic wrote that Watkins was part of a Clowns team in June with Archie Ware, Verdes Drake, and Speed Merchant and that “a better than average degree of success is just about assured for your club (with those players).”63 Later newspapers listed Honey Lott as the Clowns’ third baseman in June and in October.64

The Clowns went 29-17-1 in the first half and 18-21-1 in the second half. Philadelphia was last in both halves, going a combined 15-28-1. The Negro Leagues had a “severe case of gate famine,” and bad weather didn’t help, but they trudged to the end of 1950.65 With the Stars in 1950 Watkins hit .213 in 62 games with 32 runs and 21 RBIs; 51 of his 56 hits were singles.66

Many Negro Leaguers looked for better opportunities, and a number of players moved on to the ManDak League in Manitoba and North Dakota. At 35, Watkins joined the Brandon (Manitoba) Greys in 1950. He hit .222 in 42 games in 1950 (39-for-176); .262 in 61 games (72-for-275) with 26 RBIs in 1951; and .225 (48-for-213) with 13 RBIs in 1952. In 1951 he led the league in steals with 19. In 1952, which was Watkins’ final year in professional baseball, he led the league in fielding at .914. He also played for the Regina Caps in the Saskatchewan Baseball League in 1952.67

In addition to spending time in Canada in 1952, Watkins also played for the Orientales in the Dominican Summer League. He was one of several late-30s former all-stars on the roster, which included Cuban outfielder Pedro Formenthal and pitchers Robert Lee Griffith and Gready McKinnis.68 The Orientales also featured 47-year-old Cuban star pitcher Cocaina Garcia; Julio Rojo, who debuted in pro ball when Watkins was one year old (1916) and spent 21 years in the Cuban League; and the “Dominican Deer” and father of Dominican baseball, Tetelo Vargas who one year later led the league in hitting at the age of 47.

A year later Watkins joined his brother Lin and played for the semipro Yokely Baltimore Stars. In a game against Willie Mays’ Newport News Royals, Lin was doubled up on a fly ball to Mays to center and Murray was a part of a triple play turned on the infield.69 It is likely Watkins continued to find a place on the diamond well into his 50s. At 58 he played twice a week for a semipro team in Baltimore, the Turner Station Red Wings.70 The love of the game still tugged at him in his later years, even though he said, “Oh the legs aren’t what they used to be. But I still got good reactions and my skills are still there.” He also managed Turner Station and until the spring of 1973 he was a regular, batting leadoff.71 When asked for the key to his longevity, Watkins replied, “Nothing much. Just don’t drink whiskey and though I stay up late, I don’t go chasing after women. That combination can rot a man’s body.”72

Watkins became a father of nine and a grandfather of 14. He worked as a custodian for the Baltimore Board of Education for 22 years.73 His two older sons, Raymond and Lewis, were “both fine ballplayers,” but they gave up the game. In 1973, his 12-year-old son Murray played Little League baseball.74

The final fastball came on March 26, 1987, as Watkins died in Bolton Hills, Maryland, at the age of 71. He had told a reporter in 1973, “I’d really stop playing even now but sometimes I stand on the sidelines and watch what some of the youngsters are doing wrong and I just have to get a glove and go out there.” He did so despite the bus rides and a doubleheader in Philly followed by a night game in Baltimore (over 100 miles away), because he still missed the lifestyle. Murray Watkins was a true baseball lifer.75

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 822.

2 Ed Harris, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 11, 1940: 11.

3 JD Berthea, “Grandpa Plays Third,” Evening Star (Washington DC), June 22, 1973: E1, E4.

4 Maryland Bureau of Vital Statistics, Birth Record, Counties Index, 1910-19, W-Z, 76. msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/stagserm/sm1/sm27/000000/000011/pdf/msa_sm27_000011.pdf.

5 Associated Press, “At 58 Skeeter Still Is in the Infield,” Hanover (Pennsylvania) Evening Sun, June 13, 1973: 41.

6 Riley, 822.

7 “Newcomers Sparkle for Philadelphia Stars,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, July 21, 1941: 13.

8 “Philadelphia Nine Here for Arc Game Tomorrow at 8:45,” Stamford (Connecticut) Daily Advocate, September 3, 1941: 12. Duckett ended up being the last surviving member of the Stars when he died at 92 in 2015. John F. Morrison, “Mahlon Duckett, 92, Last Surviving Member of Philadelphia Stars,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 17, 2015. philly.com/philly/obituaries/20150717_Mahlon_Duckett__92__last_surviving_member_of_the_Philadelphia_Stars.html.

9 “Bolden’s Stars Lose 4, Win 2 as 1941 Season Nears Climax,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 6, 1941: 12.

10 Ibid.; “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1942: 7.

11 Riley, 822.

12 Effa Manley 1973 interview with John Holway, National Baseball Hall of Fame file on Manley, 6.

13 “Sullies Hits 3 Out of 4 ABs as Eagles Top Giants, 5-3,” New York Amsterdam Star-News, August 22, 1942: 10.

14 Berthea.

15 Ibid.

16 “Star Negro Teams Play Here Sunday,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 10, 1942: 24; “Grays Out to Clinch Second Half Title in Bargain Bill,” Washington Evening Star, June 28, 1942: 35.

17 “Claim Negroes in Big Time Baseball Would Hurt Semi-Pros,” Kansas City (Kansas) Plaindealer, November 27, 1942: 3.

18 Larry McShane (Associated Press), “Newark Eagles Join Hall of Fame,” May 31, 1998, National Baseball Hall of Fame archives on Newark Eagles.

19 Ibid.

20 “The African-American Newark baseball team was a source of pride and identity in segregated times,” NJ.com, February 12, 2009. blog.nj.com/ledgerarchives/2009/02/the_africanamerican_newark_bas.html.

21 Ibid.

22 Typewritten year-by-year attendance summaries at Ruppert Stadium, 1939-43, Hall of Fame archives, Newark Eagles.

23 Robert Cvornyek, Baseball in Newark (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 95.

24 NJ.com, February 12, 2009.

25 “Case Plans Charity Aid,” Trenton Evening News, April 5, 1943, 13

26 Box scores at the time listed Watkins’ spot in the order and where he played. Box score vs. Trenton, Trenton Evening News, May 3, 1943: 15; “Stars and Eagles Collide Tomorrow,” Trenton Evening News, May 20, 1943: 20; Box score, Trenton Evening News, July 13, 1943: 12.

27 “Newark Eagle Monthly Salaries,” handwritten, Hall of Fame archives, Newark Eagles.

28 Riley, 822.

29 Berthea.

30 “Murray Watkins Tops Club Poll,” Afro-American, August 18, 1945: 22.

31 Effa Manley letter to Murray Watkins, March 24, 1945, Newark Public Library Archives.

32 Wil Haygood, “Woman of Summer,” Washington Post, April 16, 2006: D01.

33 Cvornyek, 95.

34 “East-West Tilt in Chi Sunday,” New York Amsterdam News, July 28, 1945: 8B.

35 Berthea.

36 “Dressens Cop Two from Negro Stars,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1945: 131.

37 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 278.

38 “Rickey Signs Two Other Negro Stars for Nashua,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1946: 6.

39 Dan Parker, “Quotes,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1946: 18.

40 Rob Neyer and Eddie Epstein, Baseball Dynasties: The Greatest Teams of All-Time (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2000), 226.

41 Blog quote from James Overmyer’s Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press (1998). baseballthinkfactory.org/hall_of_merit/discussion/hall_of_fames_2006_negro_league_election/www.crookedbrook.com/www.crookedbrook.com/custom-embroidered-jackets.htm/P300.

42 William J. Marshall interview with Effa Manley, October 19, 1977, Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries.

nyx.uky.edu/oh/render.php?cachefile=1977oh079_chan041_manley_ohm.xml (36-minute mark).

43 Randy Dixon, “Phila. Stars Take Lead in NNL Race,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 11, 1946: 11.

44 “West Favored Over East in Dream Game in DC,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 13, 1946: 11.

45 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 453.

46 Courtney Michelle Smith, “A Faced Memory: The Philadelphia Stars: 1933-53,” Lehigh University, Theses and Dissertations, 64-65. preserve.lehigh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1743&context=etd.

47 Neil Lanctot, “Baseball: Negro Leagues,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2014. philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/baseball-negro-leagues/.

48 “Robinson’s Success Sidetracks Interest from Negro League,” The Sporting News, December 31, 1947: 4.

49 Courtney Michelle Smith.

50 Stars catcher Stanley Glenn as told to Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 1998), 159-160.

51 “Phila. Stars to Begin Spring Training April 1,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 27, 1948: 10.

52 Courtney Michelle Smith.

53 “Stars-Monarchs Plan Season’s Opener for Newark,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 12, 1943: 10.

54 “Charleston Preps Stars for Week-End Series,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 10, 1949: 10.

55 Kimmie Debnam, “Newcombe Hurls Eighth Triumph; Paige Checks Yanks,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 30, 1949: 14.

56 “Stars Continue Tour of South; Return Home July 25th,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 12, 1949: 10.

57 Personal communication from Carlos Bauer, March 2018.

58 Roster for Robinson All-Stars. docplayer.net/30613162-Rosters-of-barnstorming-and-independent-black-baseball-teams.html.

59 “Dixie Hails Jackie,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1949: 17; “Jackie’s Troupe Sets Gate Pace,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1949: 13, 20; “Jackie Draws 16,000 in NO,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1949: 18; Michael Bielawa, Janice Bielawa, Baseball in Baton Rouge (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006), 52-53.

60 Kimmie Debnam, “Sports-I-View,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 1, 1950: 11.

61 “Four N.A.L. Teams to Play in Virginia,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 22, 1950: 10.

62 “2715 Watch Kaysee Win,” Omaha World-Herald, May 24, 1950: 27.

63 Joe Bostic, “Visitors Home Team, The Scoreboard,” New York Amsterdam News, June 3, 1950: 27.

64 “Negro Tilt Sunday at Bosse Field,” Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, June 27, 1950: 18;

“Robinson’s Team Routs Local Club,” Raleigh News and Observer, October 13, 1950: 18.

65 Kimmie Debnam, “Sports-I-View,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 17, 1950: 11.

66 Personal communication from Carlos Bauer, March 2018. Watkins was listed having played for the Stars but was not listed among third basemen. White played in 30 games for Philadelphia at third.

67 1950, 1951, and 1952 League Statistics. attheplate.com/wcbl/1952_1j.html.

68 Negro Leaguers in the Dominican League. cnlbr.org/Portals/0/RL/Negro%20Leaguers%20in%20the%20Dominican%20Republic.pdf.

69 “Mays Leads Newport News to Two Baltimore Wins,” Afro-American, May 9, 1953: 15.

70 Berthea.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 Associated Press, “At 58 Skeeter Still is in the Infield,” Hanover Evening Sun, June 13, 1973: 41.

74 Ibid. We were otherwise unable to find information regarding his family.

75 Ibid.

Full Name

Maurice Clifton Watkins

Born

October 16, 1915 at Towson, MD (US)

Died

March 26, 1987 at Bolton Hills, MD (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.