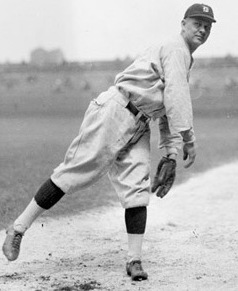

Lil Stoner

How many people can claim Benjamin Franklin, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and Washington Irving as their brothers? Lil Stoner could! The 9th edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia lists him as Lil Stoner, but he was born Ulysses Simpson Grant Stoner. Lil pitched for parts of nine seasons in the major leagues with the Detroit Tigers, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Philadelphia Phillies, from 1922 to 1932.

LuRainey May and William Caldene Stoner had eighteen children; four of them died as infants. One daughter died after being struck by lightning. On February 28, 1899, their seventeenth, Ulysses Simpson Grant Stoner, was born in Bowie, Texas. He would be given the nickname of Lil from his baby brother. Little Ted (Theodore Roosevelt Stoner) called him “Lil” because he was unable to pronounce “Ulysses.”

When young Lil was growing up in Bowie, he suffered an accident involving his brother “Mac” (William McKinley Stoner). His older brother was chopping wood in the backyard when Lil wandered over. Lil was a toddler, barely able to speak, and told his brother “chop my finger off Mac.” His brother came down with the hatchet on the index finger on his right hand. Young Lil ran into the house crying, with the finger hanging by a piece of flesh. Mrs. Stoner tightly wrapped it and had her son lie still in bed. She sent for the doctor. The doctor told her there was nothing he could do other than bandage the finger. They would have to wait to see if the finger would re-attach itself.

After a few days, the bandage came off. Although crooked, the finger had successfully re-attached itself. This deformity probably contributed to the way Stoner’s ball moved when he became a pitcher. During his pitching career, Lil was known for throwing a curve and a fastball that dropped.

Lil became interested in baseball while playing on the sandlots of Bowie, Texas. According to his mother, Lil had wanted to play baseball since he was a ten-year-old in short pants. When Stoner was thirteen, he pitched a shutout for the South Side Baptist Church team out of the Fort Worth area in the Twilight League. Many of the players were grown men.

At the age of sixteen, Lil left home in Bowie and walked to Fort Worth, where one of his uncles lived. He got a job as a pan boy at a local bakery and eventually became known as the “Bowie baker.”

Lil’s sister Georgia May and her husband followed the oil boom during that time, settling down in Morris, Oklahoma. Georgia May took a job with the local phone company, where the future Mrs. Gladys Stoner also worked. When Georgia May heard that the local oil refinery team was looking for a pitcher, she mentioned her brother. Then she told her brother about the opportunity. But before he moved north, his brother Harrison reminded him that he was responsible for their mother and baby brother Ted. So they all moved to Oklahoma, to live in Okmulgee. Lil played semi-pro for the Empire Refining Company. The team dominated all of their competition in 1918 and 1919. He would meet his wife Gladys and get married. Jean Cleo, their first child, was born in 1919.

Lil was sold to Jack Holland of Oklahoma City in the Western League. He pitched there for three seasons, 1919-21. Then Stoner traveled north to pitch for the Detroit Tigers. On April 15, 1922, Stoner made his major league debut against the Cleveland Indians. Detroit starter Carl Holling was knocked out of the box during the second inning after giving up six runs. Lil came in, pitched six innings, and walked three, allowed six hits and five runs, and struck out one. Cleveland won 11-4, sweeping a three-game series over Detroit.

On April 21, 1922, the Tigers ended their season-opening six-game losing streak. Stoner made his first start and earned his first major league victory (and the Tigers’ first of the young season) by pitching nine innings, allowing seven runs on sixteen hits while walking one in the 15-7 win.

Lil defeated the New York Yankees twice during 1922. On May 15th, he gave up three hits to beat “Sad” Sam Jones by a score of 6-1. Then on June 15th, Stoner beat Carl Mays 2-1. The Tigers looked helpless against Mays for the first seven innings but pushed across two runs in the eighth for the victory. While the Tigers squeaked out a win, the umpire barely escaped with his life. At the end of the game, Yankee players gathered around George Hildebrand, the home plate official, after he called Everett Scott out for fouling off the third shrike. There was a runner on third, and the call ended the contest. Hildebrand (credited as inventor of the spitball by some) needed a police escort to leave the game.

On July 15th, Lil Stoner’s mom was quoted in an NEA service report recalling her son’s ambition to play for Ty Cobb. She claimed that her son promised, “I’m going to play baseball with Cobb someday.” Her son should have been careful what he wished for. Stoner pitcherd poorly (7.04 ERA in 17 games) and was pitching for Birmingham by mid-summer.

Lil Stoner spent the entire 1923 season pitching for the Fort Worth Panthers of the Southern Association. The season started slow in the early spring with teams such as the Dallas Steers kicking them around. Then the Fort Worth squad caught fire, stringing together fifteen victories in a row. Al Weatherly stated in his Sporting News column: “Quite record for the pitchers in particular. Pate, Wachtel and Stoner turned in four wins in four trials and Johns turned in three wins out of four trials.” (The Sporting News, 6-14-23, p. 3) Johns’ 3-2 loss to Shreveport ended the streak.

The sports newspaper reporting the following week: “Lil Stoner of the Fort Worth Cats has been one of the exceptions to the pitching of ex-big timers. He has won more games than any other Cat hurler and is going strong. His old failing, wildness doesn’t show up much. Maybe it’s the umpiring, maybe not, but he’s a lot better than one would have supposed from his big league record.” (The Sporting News, 6-21-23, p. 3)

Nineteen twenty-three proved to be the most successful season of Stoner’s professional baseball career. He had a 27-11 record with a 2.70 ERA. The Fort Worth Panthers would finish in first place in the Texas League with a record of 96-56. They would defeat the New Orleans of the Southern League four games to two in the Dixie Series. The series, held from 1920 to 1958 was a postseason affair pitting the champions of the Southern League and Texas League. Lil Stoner won the first game of the series 3-1. That October the Tigers announced that Stoner would return to Detroit for 1924.

Stoner started off 1924 by beating the St. Louis Browns 7-4 on April 19th. Then on April 24th Lil held the Cleveland Indians to nine scattered hits while smacking a three-run homer to win, 8-2. The Detroit hurler finished the month of April with a record of 3-0 by beating Charlie Robertson (who two years earlier had pitched a perfect game against the Tigers) of the White Sox 7-2.

The Tigers began May in first place. John B. Foster of the Consolidated Press Association praised Cobb’s pitching staff. “…Whitehill, the left-handed boy from the south and Stoner who was with the Fort Worth champions of the Texas League last year, have won three games apiece. ‘Old Lil’ as Stoner is called was named as a sure winner out in Forth Worth this spring. Baseball men said he would give Detroit better pitching than any man, the Tigers had let go on option in years.” Foster claimed that if Cobb gets a valuable start especially with the help of his two young recruits, he will never fall below the Yankees all season. Shortly after his comments, Detroit fell to third place on May 3rd. They fluctuated between second and third the remainder of the season. Stoner hurled a six-hit shutout against the struggling Red Sox as the Tigers climbed percentage points of second. Still, the Tigers ended the season in third place at 86-68, six games behind the Washington Senators. Lil finished at 11-11, with an earned run average of 4.71.

Manager Cobb felt confident of the team’s chances in 1925. “My present staff, Rip Collins, Earl Whitehill, George Dauss, Ken Holloway, Sylvester Johnson, Herman Pillette, Lil Stoner and Ed Wells, may not boast a Bill Donovan but it is certainly superior to any staff that Detroit has had in my twenty years.” Davies J. Walsh, I.N.C. sports editor acknowledged, “Since 1909, a Detroit pitcher has been like the Dodo, a species long extinct.” Cobb himself admitted that the Tigers won pennants because of their hitting.

By the middle of the season, the Tigers had done little to distinguish themselves. They spent a majority of the season languishing near the bottom of the standings. Cobb never lost faith in his pitching; he praised the performances of George Dauss and Dutch Leonard. Lil pitched better than his record. His best performance was against the Indians, winning 4-1 on July 1st. He followed that game with a loss in a decent outing against the Athletics and a very impressive stint against the Yankees in a 7-3 victory. On July 21, 1925, Lil entered in relief of Whitehill during the sixth inning against the Yankees. The 26-year-old pitcher walked out to the mound to take the ball from Earl Whitehill. There were two runners on base with none out. The Yankees would score on an error by second baseman Frank O’Rourke, after which Stoner retired the next thirteen batters. After the nine innings, the game was deadlocked 4-4. Then in the eleventh inning, Lil had everything except breaks. He gave up two infield hits, and then Fred Haney threw high to first, allowing the winning run to score. The Yankees won 5-4. “A lot of folks have said all along that Stoner never would make his mark in the major leagues because he lacked pitching courage. In the last few weeks Stoner has disproved this belief. He has been confronted by some exacting situations and he has faced them unfalteringly.” (The Sporting News, 7-30-25, p. 4)

Lil won his last two starts, September 23rd beating the Red Sox 15-1 and October 4th besting the Browns 11-6. Although Detroit took the last two games against St. Louis, they still finished in fourth place, 1 1/2 games behind the Browns. Lil Stoner finished 1925 at 10-9, 4.23.

In Cobb, Al Stump noted that the great man had worn out his welcome: “The year 1926 was another case of Tiger failure: one more sixth-place finish, during which the manager, nearing forty but still carrying a Maxim gun to the plate, showed signs that after twenty-one years he and Detroit were about to part company.” An obvious ingredient of Cobb’s failure as a manager was his erratic handling of pitchers. One example is a game involving Stoner at Yankee Stadium. “It came with his pitcher, Lil Stoner breezing for a Tiger victory behind a four run lead, walked two men in a row. Showing sings of panic, Cobb Jerked him. In came Augustus “Lefty” Johns in relief. Johns was about to win the game for Stoner in the ninth inning when he gave up one hit. Cobb rushed in from right field, jerked the ball from Jon’s hand and he and Cob exchanged words. The next hurler, Wilbur Cooper, an old-timer of fading ability, gave up more hits and within minutes an almost sure win for Detroit became a defeat.” (Cobb, Al Stump, Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, 1994, p. 369.)

On June 8, 1926, Lil became a part of baseball lore. Unfortunately, he shared the stage with Babe Ruth, who received top billing. Up to this point, Stoner had never surrendered a homer to the Sultan of Swat. That afternoon during the fifth inning at Navin Field, Stoner stood on the mound, with Lou Gehrig at second base. Lil stared at baseball’s prolific home run hitter and pitched to him cautiously. The count was three balls with no strikes when Ruth found a pitch to his liking. There was no exact account of where the ball left the park, but judging from Harry Bullion’s story in the Detroit Press it was somewhere in deep right center field. Ruth’s home run received a two-sentence mention from Bullion. The writer did not seem enamored with the clout. In fact, he waited until the eighth paragraph before mentioning it. “For length, the first ride that Ruth gave the leather doubtless established a record for Navin Field or anywhere else.” Later he would describe it detail, “the ball cleared the fence with plenty to spare, skimmed along the top of parked cars on Cherry Street, landing on the asphalt pavement and a boy in pursuit of the leather caught up with it at the corner of Brooklyn Avenue.” The newspapers in New York City estimated a distance of 600 to 626 feet. They all agreed that it was Ruth’s longest in the big leagues.

Actually, Mr. Bullion seemed impressed more by Ruth’s second homer that gave the Yankees an 11-9 victory in the eleventh inning. It cleared the high wire fence in right field, striking a back wall with such a force that the ball ricocheted back onto the playing field.

Lil would not be playing for Cobb in 1927. Rumor had it that his former manager had “retired” from the Tigers and possibly baseball. The popular explanation was due to Cobb’s failure to purchase the Detroit baseball club from Frank Navin. However, in December of 1926, Dutch Leonard, a disgruntled player, accused Cobb and Tris Speaker of conspiring to throw a game between Cleveland and Detroit in 1919. Whatever the reason, Cobb was out of Detroit.

According to an article appearing in the March 31, 1927, issue of The Sporting News, “Veterans and youngsters alike seem to have profited by the coaching of Manager George Moriarty and his professor of pitching Lefty Leifield. As a result they showed improvement both mechanically and psychologically, they are better prepared to start the season than they were a year ago.” Apparently it was hard to pitch for Cobb. He would signal from the bench or center field to the mound. He had a habit of removing pitchers during a potential rally, so the 1927 staff was determined to prove their former manager wrong. In the same Sporting News, “Stoner, like Gibson is developing a ‘change of pace’ and if he succeeds in mastering that delivery, he should win a number of games for Detroit after the campaign ends. For several years, Stoner has threatened to become a winning pitcher. His curveball and his fast one have to be good enough to lift him into the category, but Stoner has lacked a change of pace and pitching poise.”

Around the halfway point of the 1927 season, it appeared Lil Stoner would finally reach his expected potential. Up until now, he had been a puzzle. While Lil always had the stuff, he lacked consistency. Many claimed that he did not have the poise necessary to be successful. But going into the last week of June, Lil found himself with a 6-1 record and one of the leading pitchers in the Junior Circuit. His only loss was 2-0 to Dutch Ruether and the New York Yankees on June 2. He then beat the Red Sox twice during a series with them, 5-3 as a starter on June 8th and June 11th in relief. On June 16th, he tossed arguably his best game of the season by defeating the Washington Senators 6-1 to move his club over .500. Lil was embroiled in a pitcher’s battle with Hollis Thurston, until Detroit pushed across a run in the eighth inning; they clinched the game by scoring three more runs courtesy of two hits and two errors. Washington would ruin the shutout with a run in the bottom of the inning. Lil Stoner wound up with 4 hits in the 6-1 win.

The Tiger put together a thirteen-game winning streak between August 10th and 22nd. Their fortunes would reverse from August 24th until September 15th, as they won only four out of twenty four games. Stoner lost his last five starts. The team scored six times as he surrendered twenty-seven runs over this stretch. Lil finished 1927 with a record of 10-13 and an ERA of 3.98. Detroit came in fourth, 27 1/2 games behind the New York Yankees.

The rap on the Detroit Tigers had always been the lack of pitching. At the start of the 1928 season, The Sporting News announced that the baseball world could no longer blame Detroit’s hurlers. Many of the game’s experts ranked the Tigers one of the four strongest teams. Unfortunately, halfway through the year, the staff would collapse. With the exception of Owen Carroll, the staff has been disappointing. Lil ended the season at 5-8 and 4.36 ERA. The team fell to sixth place with a record of 68-86.

Before the 1928 spring training camp for the Detroit Tigers, a picture and story appeared in newspapers across the nation. It showed Lil posed alongside an orange sponge cake. It was 3 tiers high, iced in white, ornamented with green icing, lavishly decorated with paper leaves and flowers. It had 45 candles. Stoner baked it especially for a friend who was celebrating his 45th birthday. Towards the end of Stoner’s major league career, his cooking ability became well known. In fact, there were those who claimed that he might not be the best pitcher in the big leagues, but no one would argue his cooking ability! His eldest daughter, Jean, claimed that during the Depression, the Stoner family always had food on the table. She remarked that her father was a nutritionist before anyone knew what nutrition was.

Lil got off to a great start in 1929. He won his first three starts before April 29th, but then things went south, banishing him to the bullpen. One example of his luck occurred on July 11th when he relieved John Prudhomme of Boston. Prudhomme left the game after giving up four runs in two innings. Stoner entered the game and shut out the Red Sox the first three innings. Then in the sixth, Stoner and Josh Billings faced sixteen batters between them, the first nine scored, and the Tigers lost 15-8.

Stoner pitched in twenty-four games with Detroit that season. His record was a disappointing 3-3, with four saves and an ERA of 5.29. Once again, Lil was sent off to the Fort Worth club of the Texas League. The “Bowie Baker” never returned to Detroit. The Tigers finished another season in sixth place with a 70-84 record.

Lil started the 1930 season with the Pittsburgh Pirates but returned to the Texas League to finish the season. Many felt that Stoner was a pitching puzzle with a piece missing. The opposite was true when he played in the Texas Leagues. Not only did he have all of the pieces, but they fit together perfectly! For example, his greatest single season was in 1923. Lil posted a ledger of 27-11 with an ERA of 2.70. The 1930 season was also dominating. On Friday, June 13th, Lil hurled a no-hit game. He faced only 27 batters and missed a perfect game, issuing one walk; the baserunner was thrown out stealing. On July 30th, he struck out 18 San Antonio batters during a 5-1 victory. He finished the campaign with a 14-6 record and an ERA of 3.24. Forth Worth made another trip to the Dixie Series. Unfortunately, a bad hand ended Lil’s participation after the first game that he pitched. Lil was hit in the hand while batting in his first appearance. Lil complained of deadness in his hand. The x-rays came back negative.

Stoner’s 1930 performance at Fort Worth earned him an audition with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1931. He pitched a few exhibitions and appeared in seven regular season games, finishing 0-0. He returned to Fort Worth. Lil’s stay in Texas was not very long. The team shipped him off to Newark, New Jersey, commonly referred to as the 17th big league team of the 16-team major leagues. Stoner appeared in 10 games, finishing with a 2-0 record.

He bounced around in 1932 but could not regain his old pitching talent. He played for Omaha of the Western League, then the Houston Buffs of the Texas League. Seven years later he resurfaced on the baseball diamond in 1939 for the Enid Champlin Refiners semi-pro team. Nick Urban, the team’s manager, felt that this year’s team was improved offensively with the addition of Lonnie Goldstein and Lil Stoner. Both players demonstrated their hitting ability against this level of pitching. The Refiners were formally known as the Eason Oilers, who won the national title in 1937 and lost in the finals against a team from Buford, Georgia, in 1938.

On August 8, 1939, the Enid Champlin Refiners took the finals of the 24th Denver Post semi-pro Baseball tournament. They kept their undefeated record intact by overcoming a 6-0 deficit by scoring two runs in the eighth to tie it and win in the tenth on a pair of walks and an error. Stoner, who was on third, took advantage of an overthrow by Nix, as the Buford reliever violated baseball logic by overthrowing to first base on a pickoff attempt, allowing Lil to score from third base.

Aside from cooking, Stoner became accomplished at growing irises. He was considered such an expert that he was asked to travel statewide to judge irises in flower shows. His proudest botanical accomplishment was his creation of a pink iris hybrid.

While most Texans tended to be Country and Western music fans, Lil’s daughter Jean Harmon says that Lil was a devoted opera fan. His interest began while he was playing in Detroit. A teammate had tickets for the opera and gave them to Lil. Stoner attended and was forever hooked. According to Jean, her father had amassed quite a collection of opera records. Caruso was his favorite.

Ulysses Simpson Grant Stoner died in Enid, Oklahoma, on June 26, 1966, following a brief illness. He sat in his hospital bed, eating a meal, listening to a ballgame on the radio. At some point, he scratched his head and died. Lil was sixty-six years old. He is buried in Memorial Park Cemetery in Enid.

Lil Stoner had a career record of 50-58 with an ERA of 4.76 over nine major league seasons. He played with the Detroit Tigers and briefly with the Phillies and Pirates.

But when the “Bowie Baker” had all the ingredients, he produced a real delicacy!

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet

Baseball Almanac

The Baseball Index

SABR Encyclopedia (SABR Members)

Interview with Jean Harmon, Lil Stoner’s daughter, on November 3, 2007 (via telephone)

List of Lil Stoner’s siblings provided by Christy Pruett (Great Grand daughter)

Howe Bureau card (from Rod Nelson)

Cobb, by Al Stump, Alonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, 1994.

The Encyclopedia of the Minor Leagues, by Miles Wolff and Lloyd Johnson, Durham, NC, 2nd ed.,1997.

“Stories of Long Home runs, Just Like Fish Tales,” by Joe Fields, The Sporting News, April 29, 1967.

The Sporting News, July 13, April 5, June 21, August 11 and August 18, 1922, March 31, 1927

“Tigers Fail to Give Pitchers a Chance,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1928

Lima News, Lima OH, 4-16-22, 4-22-22

Chronicle Telegram, Elyia, OH, 4-22-22

News Sentinel, Fort Wayne, IN, 5-16-22

Lincoln Star, Lincoln, NE, 6-16-22

Daily Globe, Ironwood, MI, 6-16-22

Nevada State Journal, Reno, 6-19-22, 8-14-22

“Lil Stoner’s Ambition to Play With Cobb Realized,” Modesto Evening News, Modesto, CA, 7-15-22

Bridgeport Telegram, Bridgeport, CT, 9-6-22, 8-28-25

Mexia Daily News, Mexia, TX , 8-12-23, 4-25-24

Appleton Post-Crescent, Appleton, WI, 4-25-24

Reno Evening Gazette, Reno, NV, 5-1-24

Portsmith Daily Times, Portsmouth, OH, 6-17-24

Charleston Gazette, Charleston, WV, 6-17-24

Woodland Dailey Democrat, Woodland, CA, 7-24-24

Port Arthur News, Port Arthur, TX, 7-31-24, 8-9-25

San Antonio Express, San Antonio, TX, 12-1-1924

New Castle News, New Castle, PA, 3-6-1925

Oakland Tribune, Oakland, CA 5-30-26

Lancaster Dailey Gazette, Lancaster, OH, 3-5-1929

Galveston Daily News, Galveston, TX, 9-2-30, 6-30-32

El Paso Herald-Post, El Paso, TX, 6-19-31

Bismarck Tribune, Bismarck, ND, 3-6-31

Salt Lake Tribune, Salt Lake, UT, 8-12-31

Morning Herald, Uniontown, PA, 9-14-31

Ada Evening News, Ada, OK, 4-6-39, 8-8-39

Abilene Reporter, Abilene, TX, 8-8-26

Full Name

Ulysses Simpson Grant Stoner

Born

February 28, 1899 at Bowie, TX (USA)

Died

June 26, 1966 at Enid, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.