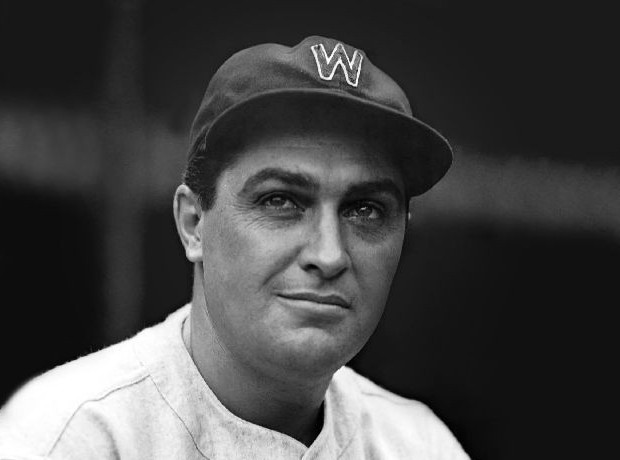

Earl Whitehill

Earl Whitehill, one of the solid yet increasingly anonymous pitchers of the 1920s and 1930s, played 17 major league seasons and remains one of the top 100 winning pitchers of all time. A southpaw, he mixed a tantalizing curve with a fiery disposition to win 218 games for the Detroit Tigers, Washington Senators, Cleveland Indians, and the Chicago Cubs.

Earl Whitehill, one of the solid yet increasingly anonymous pitchers of the 1920s and 1930s, played 17 major league seasons and remains one of the top 100 winning pitchers of all time. A southpaw, he mixed a tantalizing curve with a fiery disposition to win 218 games for the Detroit Tigers, Washington Senators, Cleveland Indians, and the Chicago Cubs.

The son of Noah and Margaret Whitehill, Earl hailed from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, which he called home throughout his life. Born February 7, 1899, he also had a sister, Edna, born in 1900, and a brother, Edward George, who was born fourteen years later. His height is listed in various places between 5′ 9 1/2″ to 5′ 10″, at a weight of about 175 pounds, although his Draft Card from World War I only declares him to be of medium height and slender build.

Discovered by fellow Cedar Rapids native Cy Slapnicka, who scouted for the Tigers before switching his allegiance to Cleveland, Whitehill began ascending the ziggurat of organized baseball at 21 when he reported to Birmingham in the Southern league in 1920. Arriving in late season, he pitched only one game, a loss, and was shipped down to Columbia of the South Atlantic league. The next year, a 20-10 record hastened his return to Birmingham.

He won 54 games during his minor league seasons, losing 41. Clearly ready for the big time, Detroit purchased his contract from Birmingham and brought him up to play for manager Ty Cobb in 1923. He made his first appearance on September 15 1923, at age 24, and ultimately appeared in 33 innings over eight games while garnering a record of 2-0. In 1924, Whitehill became a Tigers starter, replacing 34-year-old Hooks Dauss, who was sent to the bullpen. He validated Cobb’s judgment that season by leading all AL rookies with 17 wins and a .654 winning percentage.

In 1924 he married 22-year old Violet Oliver. There has persisted through the literature a popular ‘urban legend’ mythology that she was the original model for the Sunmaid Raisins “maiden”. The Sunmaid Raisin company has since publicly stated that Lorraine Collette Peterson was the actual model1, and there is no record of Violet being painted or drawn for the role in 1916, when the image first adorned the raisin boxes. She was, regardless, a beautiful woman, and the couple doubtlessly drew attention wherever they went. She became close with Clare Ruth during the Connie Mack/Babe Ruth 1934 barnstorming tour of Japan, and the two couples were friendly off the field. Of course, the Bambino loved facing Whitehill on the field, too, as Ruth tagged him for eleven of his 714 career homeruns (only six pitchers ceded more 4-baggers to the Babe).

Later in life, all may not have been happy, as (upon Whitehill’s death) there was rumored to be a divorce petition on file, but there is no evidence of a formally granted decree. In 1931, however, all was happy enough as the Whitehills welcomed their only child, daughter Earlinda.

Over 10 years Whitehill posted a 133-120 record for the Tigers. Control was a feature of his game, and he used his array of off-speed pitches to win 14 or more games ten times, too often for mediocre teams.2 In 1931, two years after the Yankees began issuing uniform numbers to players, Whitehill was assigned number 11 by the Tigers. He was switched to 15 in 1932.

On December 14, 1932, the Tigers traded Whitehill to Washington for pitchers Fred “Firpo” Marberry and Carl Fischer. The following season began in turmoil. In April, as a consequence of pitching inside, Whitehill hit Lou Gehrig–at the time closing in on Everett Scott‘s 1,308 consecutive-games-played record–and knocked him unconscious. Obviously, Gehrig recovered, but Whitehill continued to finding himself in the midst of maelstroms. In May, as part of an imbroglio between the Yankees’ firebrand Ben Chapman and Senator shortstop Buddy Myer, Whitehill even achieved notoriety in Time magazine:

When Chapman reached the passageway on his way off the field. Earl Whitehill, Washington pitcher, called him a bad name. This was more than Fielder Chapman, already humiliated, could bear. He rushed at Whitehill, hit him. Umpire Moriarty tried to pull the fighters apart but failed. This time, all the players on both teams rushed at each other not to stop the fight but to enlarge it. Private detectives, uniformed policemen and about 300 spectators rushed down on the field. The spectators, armed with bats they had picked up, tried to bash the players. The players bashed each other and the spectators. After 20 minutes, police managed to restore enough order for the ball game to proceed. After five more innings, the Yankees won 16 to 0.3

Although he hadn’t been a teammate for long, the teachings of Ty Cobb had manifested themselves throughout Earl’s career. Chapman got his revenge the next year, however, breaking up a potential Whitehill no-hitter against the Yankees on May 30, 1934.

Perhaps due to being reassigned number 11 (the number he’d keep throughout his tours of duty with the Senators and the Indians) Whitehill led the AL in games started and was near the top in most pitching categories in 1933. His 22 victories (against only 8 losses) were a career-best, and his ERA of 3.33 was a full run below his lifetime figure. That autumn, in the World Series, he defeated Freddie Fitzsimmons 4-0 in Game Three, throwing a five-hitter.

As demonstrated, his temper could be both fierce and short. He achieved the dubious “century mark” on the mound by hitting 101 pitchers over his career, and is popularly regarded as a temperamental pitcher who often showed up in the top 10 in hit batsmen. He led the league in that category in his first full year, 1924, when he hit 13 (tied with George Uhle). Later, in 1934, when Cleveland slugger Hal Trosky was a rookie, he made the mistake of digging in against Whitehill. That led to a fastball in the ribs, and a painful walk/jog down to first. To Trosky’s credit, he learned his lesson. He and Whitehill, both Iowans, became very close friends after their playing days were over.

In Elden Auker‘s Sleeping Cars and Flannel Uniforms4, the former Tiger relates a story about a time he and Whitehill played golf in Arizona during Tiger spring training. Well down the fairway, a golf ball suddenly landed close to Earl, and he charged back to the tee box to “take care” of the hacker. Providentially, his fellow golfers talked him out of the quest, as later on they learned that the “assailant” was actually heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey.

His temper notwithstanding, Whitehill had his best season was 1933, and his pitching was largely responsible for the Senators finding themselves in the World Series against the Giants. During that contest, New York enjoyed a 2-0 series lead when Whitehill took the hill for the third game. He made the most of his only World Series appearance by tossing a complete game shutout of the Giants, scattering five hits and two walks in front of 25,727 at Griffith Stadium. In doing so, he also held future Hall-of-Famers Mel Ott and Bill Terry to a collective 0-for-7 day at the plate. On the biggest stage, Earl brought his best stuff.

Whitehill played three more consistent, winning seasons for Washington, despite one aberrant game in 1935 in which he gave up ten doubles, but on December 10, 1936, he anchored a three-team trade that sent him to Cleveland. The Senators received Jack Salveson from the White Sox, while Chicago took Thornton “Lefty” Lee from the Indians.

In Cleveland, Whitehill appeared mostly in relief. He won 17 and lost 16 for the Indians in the 1937-38 seasons and in February 1939 was released. The Chicago Cubs assigned him number 31 for the 1939 season, and he finished that year, the last of his career, with a 4-7 record. At the end, he was the oldest player in the National League and was throwing to 38-year-old Gabby Hartnett. His final game was on September 30, 1939.

The Indians hired him as a coach for manager and former Cobb teammate Ossie Vitt in 1940, but let him go in 1941. His final stop in the majors, after a season in the International League, was as coach of the Philadelphia Phillies in 1943. After that, he took up traveling sales of sporting goods, using his name and energy in representing the A.G. Spalding Company.

His lifetime record compares well with luminaries such as Bob Feller and Red Faber. Feller appeared in 570 games and won 266; Faber in 662 games, winning 254; Whitehill played in 541 games, won 218 against 186 losses, and amassed 3,562 innings of big league baseball. Unquestionably durable, he tossed an amazing 226 complete games and walked only 1,431 batters. On the not-so-good side, he was not a deft fielder, twice committing seven errors in a single season.

He was inducted into the Des Moines Register’s Iowa Sports Hall of Fame in March 1963. While not a Baseball Hall-of-Fame player (his vote totals were: 1956 – 1 – .5%; 1958 – 2 – .8%; 1960 – 3 – 1.1%), he was a solid pitcher and teammate for three American League teams. Spanning the generations from Cobb to Williams, he was a terrific pitcher in what is generally regarded as a hitter-dominated era. None other than “Cool Papa” Bell, of the Negro Leagues, noted in an American Heritage interview with John Holway, that “Earl Whitehill was the toughest big-league pitcher I ever faced. In 1929 we beat the major-league all-stars six out of eight games, and Whitehill beat us both times”.5

In late 1954, at an intersection in Omaha, Nebraska, another car flew through a stop sign and T-Boned Whitehill’s car. Though shaken, he refused to go to the hospital on the night he was injured. The next day, however, he was forced to visit a doctor, and the medical team discovered that the pitcher had suffered a fractured skull. Whitehill lived for another week, but passed away on October 22. He is buried at Cedar Memorial Park, near his home of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Last revised: August 16, 2021 (zp)

Notes

1 http://www.sunmaid.com/about/sunmaid_girl

2 McGrane, B. Cedar Rapids Gazette; March 24, 1963 “Earl Whitehill”

3 Time, “Baseball Fight”, May 8, 1933

4 Auker, E. (2006). Sleeping Cars and Flannel Uniforms. Triumph Books, Chicago, IL

5 James “Cool Papa” Bell and John Holway, “How To Score From First on a Sacrifice”, American Heritage, May 1970. Available online: http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1970/5/1970_5_30.shtml

Full Name

Earl Oliver Whitehill

Born

February 7, 1899 at Cedar Rapids, IA (USA)

Died

October 22, 1954 at Omaha, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.