Lou Criger

Feisty, slender, and packing a strong, accurate throwing arm, the smarts to call pitches for the winningest pitcher of all time, and the resiliency to last despite facing many physical ailments, catcher Lou Criger was regarded by his peers as one of the best backstops of the Deadball Era. At 5-feet-10 (some sources say six feet) and 165 pounds, Criger made an inviting target for bigger opponents, but the slender receiver took the punishment and held his ground. “Many players tackled Criger because he looked like a weakling,” said Louie Heilbroner, who managed him in St. Louis before the respected receiver jumped to the American League. “But Criger would fight any six men on earth in those days, and if someone didn’t pull them apart, Lou would lick all six by sheer perseverance.”

Feisty, slender, and packing a strong, accurate throwing arm, the smarts to call pitches for the winningest pitcher of all time, and the resiliency to last despite facing many physical ailments, catcher Lou Criger was regarded by his peers as one of the best backstops of the Deadball Era. At 5-feet-10 (some sources say six feet) and 165 pounds, Criger made an inviting target for bigger opponents, but the slender receiver took the punishment and held his ground. “Many players tackled Criger because he looked like a weakling,” said Louie Heilbroner, who managed him in St. Louis before the respected receiver jumped to the American League. “But Criger would fight any six men on earth in those days, and if someone didn’t pull them apart, Lou would lick all six by sheer perseverance.”

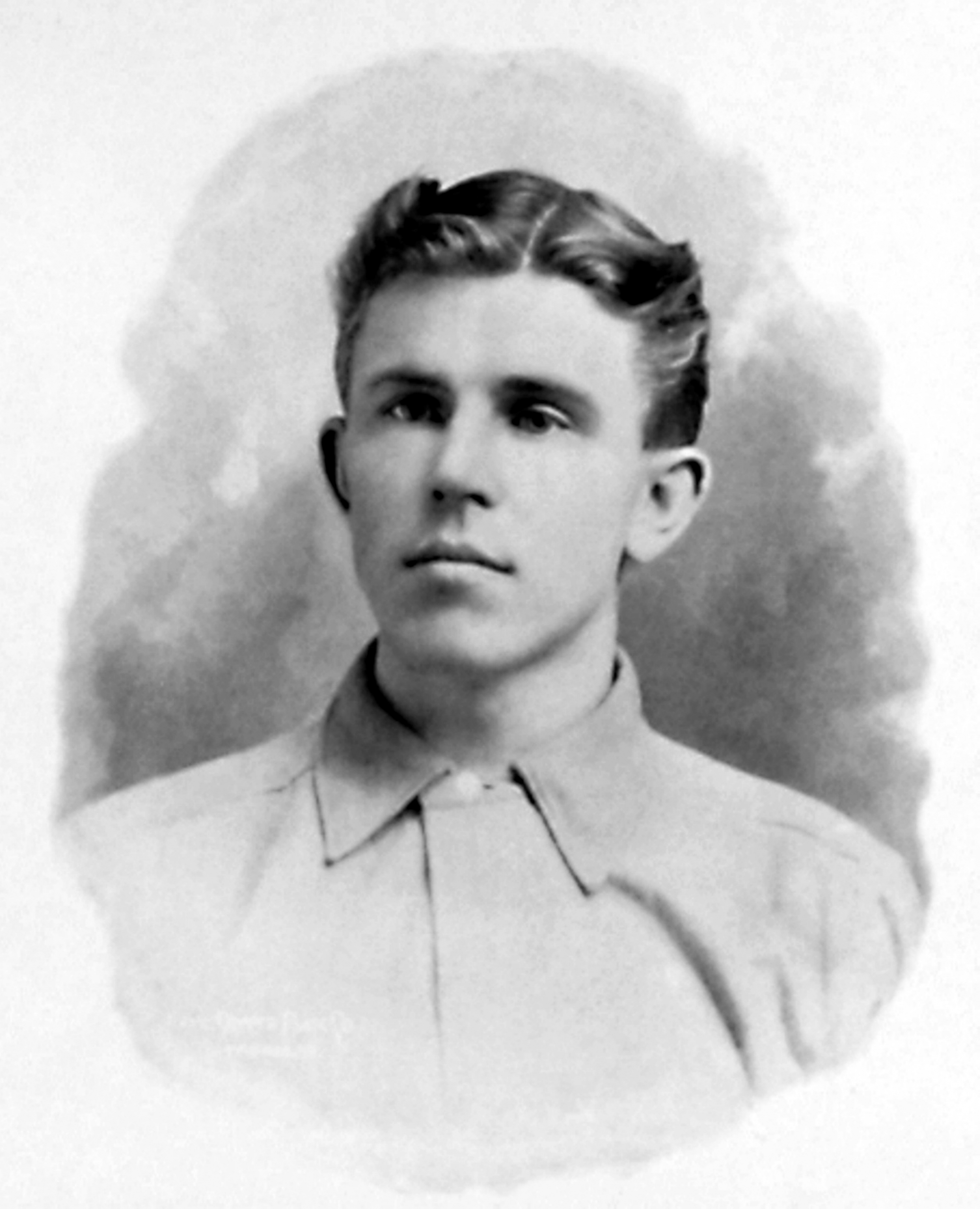

A 1910 newspaper account described Criger as having light chestnut hair, porcelain colored eyes, a countenance something like Julius Caesar’s, and so slight that he “looks anything but athletic.” But looks can deceive, as Criger proved by using his arm and his cunning as weapons worthy of journalists’ praise. Wrote Boston writer and former player Tim Murnane, “Criger is the man who can turn back the fleetest base runner, a man who can nip the boys at first and third unless they are ever on the alert. Criger is the backstop that never drops a ball that he can reach, and who can throw harder and quicker to second than any catcher in the profession. … I would like to see some one pick out the equal of Criger.”

Louis Criger was born on February 3, 1872, on a farm just south of Elkhart, Indiana, to Charles Criger, a cooper originally from the Mecklenburg region of Germany, and Lovina (Stutsman) Criger. Lou had five brothers, one of whom, Elmer, pitched in the minor leagues, winning 22 games with Jackson of the Southern Michigan League in 1909 and earning a place with Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League. In 1890 Lou Criger pitched for the Elkhart Lakeviews. The following year, he moved behind the plate, where he became a mainstay for the newly organized Elkhart Truths.

After spending five seasons playing for Elkhart, Criger was signed by the Michigan State League’s Kalamazoo Kazoos in 1895. The next year he began the season with the Fort Wayne Farmers of the Inter-State League, splitting his time between left field and catcher and typically batting third or fourth in the lineup. One of his Fort Wayne teammates was R.C. Grey, whose brother Zane, a semipro player, went on to fame as an author of Western fiction.

Criger joined the Cleveland Spiders at the end of 1896, going hitless in five at-bats. He began 1897 year as a third-string catcher for the Spiders, but when he finally got a chance to play, he dazzled observers with his powerful throwing arm, gunning down all six would-be Louisville base stealers on June 22, 1897. Criger took great pride in his throwing; he often sounded like a pitcher when he discussed his technique. “Now the way I throw the ball, it rotates backward and has an upward tendency, while some catchers throw with the thumb exposed and that gives it the downward effect, like the billiard draw shot, a ball that hurts to catch,” he told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1909.

In 1898 Criger became the Spiders’ primary receiver, appearing in 82 games behind the plate and batting a modest .279 with one home run. That turned out to be the best offensive performance of the right-handed batter’s career. A classic example of the good-field, no-hit catcher, Criger batted just .221 during his 16-year-career, and never collected more than 22 extra-base hits in a single season. He played because of his stellar defensive work and his close relationship with Cleveland ace right-hander Cy Young.

From 1897 to 1908, wherever Young went, Criger joined him: with Cleveland in 1897 and 1898, St. Louis in 1899 and 1900, and the Boston Americans from 1901 to 1908. During those 12 seasons Young won 283 games, and Criger was behind the plate for most of them. As Sporting Life put it in 1908, “What battery still serving in the major leagues has more inseparable service than the firm of Young and Criger?” In 1910 Young called Criger “the greatest catcher that ever stood behind the plate.” But catching the burly hurler took its toll. Recalled his son, Harold Criger, in 1988, “I remember when the ball hit the mitt, it sounded like a pistol shot, and when dad was home, he soaked his hand in hot water, and it was red as fire. Sometimes he put a slice of beefsteak in his mitt for more padding, and Cy beat it to bloody shreds.” After the two parted ways – Boston traded Criger to the Browns in December 1908 – Young talked to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about what the 1909 season might be like without Lou. Said Young, “In Criger, St. Louis will get one of the greatest catchers that ever donned a glove. I’ve pitched to him so long than he seems a part of me, and I am positive no one will suffer from the departure more than I. Lou is a great student of the game and knows the weaknesses of every batter in the league. So confident am I of his judgment that I never shake my head. It means that I have to learn a great deal about the batters, features to which I had heretofore paid no attention.”

Criger was behind the plate for some of Young’s greatest games, including his perfect game against the Phildelphia Athletics at the Huntington Avenue Grounds on May 5, 1904, and his no-hitter against the New York Highlanders at Hilltop Park on June 30, 1908. Criger also caught all 20 innings of Young’s famous duel with Rube Waddell on July 4, 1905. In 1903 the backstop was behind the plate for every game of Boston’s eight-game triumph over the Pittsburgh Pirates in the first modern World Series. Twenty years after that success, Criger revealed that he had turned down a $12,000 offer from a gambler named Anderson to call “soft pitches” during the Series. In 1923 Criger, believing he was dying of tuberculosis, hired an attorney to file an affidavit with American League president Ban Johnson, who went public with the incident. Johnson, impressed with Criger’s honesty, personally established a pension that helped Criger and other players after their playing days.

During his playing career Criger endured his share of bumps and bruises, a subject about which the catcher was particularly sensitive. While recuperating from a damaged finger during the 1901 campaign, Criger told Sporting Life, “They are very solicitous about my health. Just tell them for me that I am feeling perfectly well. I am out of the game just now with a bad finger, but will be in all right, and think I am good for many more years of ball playing before I quit. Every now and then someone sends me a clipping in which it is stated that I am not well. It is extremely annoying, not only to me, but to my folks.” Nonetheless, Criger became so associated with injury that he later became a spokesman for the Elkhart-based Dr. Miles’ Anti-Pain Pills.

With batterymate Cy Young nearing the end of his career, Criger was traded to the St. Louis Browns in December 1908 for catcher Tubby Spencer and $5,000 (some sources say $4,000). In one season with St. Louis, Criger batted just .170 with two extra-base hits in 212 at-bats. After the season Criger was again traded, this time to the New York Highlanders for pitcher Joe Lake and outfielder Ray Demmitt. Criger appeared in only 27 games for the Highlanders and batted just .188. The following year he played briefly for Milwaukee of the American Association and was player-manager for Boyne City of the Michigan State League. In 1912 Criger returned to the American League as pitching coach for the Browns. The 40-year-old played in one game when both Browns catchers got hurt.

Criger married the former Belle Louise Wolhaupter in 1893. They and their six children lived in Elkhart until 1909, when the family moved 22 miles northeast to a 40-acre farm at Bair Lake, Michigan. There, he spent many an offseason hunting and fishing with his ballplaying friends. In 1914 Criger developed tuberculosis in his left knee, and the following year his leg had to be amputated above the knee. In failing health, Criger moved to Nevada in the early 1920s and in 1924 relocated to the arid climate of Arizona, spending winters in Tucson and summers in Flagstaff. The family ran a bakery in Tucson. In 1920 Criger’s son Rollo, also a catcher, joined the St. Louis Cardinals but never appeared in a game.

Criger died on May 14, 1934, in Tuscon and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in that city. A Northern Indiana SABR chapter was named for Criger in the spring of 1998.

An updated version of this biography appeared “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans,” edited by Bill Nowlin (SABR, 2013). The biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

Sporting Life

Elkhart Truth

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Jeanette Criger Done (granddaughter and family historian)

Full Name

Louis Criger

Born

February 3, 1872 at Elkhart, IN (USA)

Died

May 14, 1934 at Tucson, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.