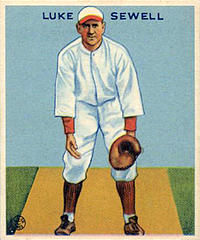

Luke Sewell

The 1933 season was in only its third week when the Washington Senators made a stop in New York to face the world champion Yankees in a two-game series, on April 28 and 29. For the Senators, it was an important series, as they were headed west on an 11-game trip in early May. They finished off the Yankees in the first game, 4-3 in ten innings. The next day Washington had a 6-2 lead behind starter Monte Weaver. Weaver, who had surrendered only four hits in the first eight innings, gave up three consecutive hits to start the ninth; Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Dixie Walker all singled to cut the deficit to 6-3. With Gehrig at second base and Walker on first, the crowd of more than 35,000 cheered wildly when second baseman Tony Lazzeri stepped to the plate. “Poosh ‘Em Up” crushed an offering by Weaver to deep right-center field. Goose Goslin gave chase, but the liner averted his grasp. Gehrig had not strayed far from second base, to make sure Goslin did not catch the smash. But Walker was running all the way and when Gehrig did take off, Walker was right behind him.

The 1933 season was in only its third week when the Washington Senators made a stop in New York to face the world champion Yankees in a two-game series, on April 28 and 29. For the Senators, it was an important series, as they were headed west on an 11-game trip in early May. They finished off the Yankees in the first game, 4-3 in ten innings. The next day Washington had a 6-2 lead behind starter Monte Weaver. Weaver, who had surrendered only four hits in the first eight innings, gave up three consecutive hits to start the ninth; Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Dixie Walker all singled to cut the deficit to 6-3. With Gehrig at second base and Walker on first, the crowd of more than 35,000 cheered wildly when second baseman Tony Lazzeri stepped to the plate. “Poosh ‘Em Up” crushed an offering by Weaver to deep right-center field. Goose Goslin gave chase, but the liner averted his grasp. Gehrig had not strayed far from second base, to make sure Goslin did not catch the smash. But Walker was running all the way and when Gehrig did take off, Walker was right behind him.

Goslin retrieved the ball and fired it into the relay man, shortstop and manager Joe Cronin. Cronin wheeled and threw home to catcher Luke Sewell. Gehrig was surprised the ball beat him to the plate, and did not slide. Instead, he seemed to break his stride just a bit, as Sewell tagged him with the ball clutched in his right hand. Gehrig hit Sewell hard, spinning him completely around. Recovering, Luke dived toward the third base line to tag the oncoming Walker, who had slid to the inside of the plate. Walker was out, and the unorthodox double play was completed.

The play turned the Bronx fans’ cheers into groans. Gehrig and Walker were both in disbelief. Weaver was also a bit stunned. “It’s two outs, Monte,” the veteran catcher made clear to Weaver. “Oh, do we have two outs?” replied the puzzled pitcher. “It was a swell job by Goslin and Cronin,” said Sewell. “I didn’t have to move for the ball. It was easy. Cronin can sure pitch the ball.”

Indeed, it was only a two-game sweep, but the Senators served notice that they were a viable contender in the league. And the acquisition of the veteran catcher from Cleveland was one reason why Cronin felt that way; he had proclaimed that Sewell was the “best receiver in the business” when the deal was made during the offseason. And indeed, the veteran of 12 major-league seasons justified Cronin’s confidence, giving a sterling performance behind the plate and helping rookie manager Cronin handle his pitching staff as the Senators won the American League pennant.

James Luther Sewell was born on January 5, 1901, in Titus, Alabama. He was the second youngest of six children born to Dr. Wesley Sewell and Susan Sewell. Dr. Sewell was a general practitioner, but it was a baseball family. Luke’s older brother, Joe Sewell, was a star shortstop for Cleveland and later a third baseman for the Yankees, set records for the fewest strikeouts by a batter, and was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977. Younger brother Tommy Sewell played in one game and had one at-bat for the Chicago Cubs in 1927.

Luke was two years younger than Joe, but their parents enrolled them in school together. Luke showed a high aptitude for learning, holding his own with the older children in a one-room schoolhouse. He got his nickname from an elementary-school teacher.

Luke and Joe both went to Wetumpka High School. Luke was only 15 when he enrolled at the University of Alabama with his older brother. They both played football for the Crimson Tide, although it was baseball where first Joe, then Luke was noticed. After his graduation in 1920, Joe signed a contract with New Orleans of the Southern Association. When Ray Chapman was fatally struck in the head by a Carl Mays pitch, and his replacement was soon injured, Joe was promoted to Cleveland. The Indians won their first world championship in 1920, and Joe Sewell’s contributions were a big part of the team’s success.

As Joe departed Alabama, Luke stayed behind working on his degree. “We could have graduated together, but I had nothing to do, so I stayed and took a few extra courses,” he explained. He was an outfielder and second baseman on the Alabama baseball team, but a broken ankle started his career as a backstop. In a game against Mississippi in his junior year, the regular catcher was having trouble handling the muddy sphere as well as throwing out baserunners. Coach Xen (for Xenophon) Scott decided that because of the injury Sewell was not mobile enough to play in the field, and put him behind home plate. From then on he was the starting catcher.

Luke signed with Cleveland and was assigned to Columbus (Ohio) of the American Association. But after only 17 games, he joined manager Tris Speaker’s team in Cleveland and was in the major leagues for good.

For his first three years Sewell was as the bullpen catcher and backup to Steve O’Neill. He studied the intricacies of catching, like tagging a sliding player at the plate with the baseball held firmly in his right hand, not in the oversized catcher’s glove. He studied opposing hitters and their tendencies at the plate. “Those were not wasted years. I was busy studying baseball,” he recalled. He observed that you “don’t just play baseball; you play it against another team.”

O’Neill was traded to the Boston Red Sox after the 1923 season, and Sewell began to split playing time with Glenn Myatt. Myatt was a better hitter, but Sewell had a stronger arm, handled the pitching staff well, and was a better defensive catcher. By 1926 Speaker chose Sewell as his starting backstop. Sewell had 91 assists that season, the first of three straight years in which he led the league in that statistic. The Indians chased New York all season, making things interesting in mid-September when the Yankees invaded League Park for a six-game series. More than 100,000 paying customers pushed through the turnstiles at League Park as the Indians won four of six games and closed the gap to 3½ games with seven to play. But they got no closer. On August 14 of that season he married Edna Ridge of Akron, Ohio, daughter of a rubber magnate William Ridge. They had two daughters, Suzanne and Lois.

In the shadow of a gambling scandal, Speaker was forced to retire as a manager after the 1926 season. The Indians did not fare well in the pennant race under his successors, Jack McCallister and Roger Peckinpaugh. Neither could muster a team that could rival the great Yankee or Athletic teams of the era. Sewell continued as the regular catcher from 1927 through 1929. Injuries curtailed his playing time in 1930; he missed seven weeks when a foul tip off the bat of Washington’s Jack Hayes broke his right forefinger. He caught 76 games that season. In 1931 he caught in 104 games but in 1932 he was back to splitting time with Myatt.

On April 29, 1931, Sewell was the backstop for the first of three no-hit games he caught. Wes Ferrell threw the masterpiece against the St, Louis Browns at League Park, striking out eight while walking three batters. Sewell contributed at the plate, going 2-for-3 with an RBI, two runs scored and a walk. In 1932 he caught in 84 games.

Joe Cronin was named manager of the Washington Senators for 1933, replacing Walter Johnson. Cronin wanted to see the catching improved. Washington’s regular receiver, Roy Spencer, was often injured and not a particular favorite of Cronin’s. But the Indians liked Spencer and on January 7, 1933, they were traded for each other.

Cronin was optimistic about his team’s chances of raising the pennant in the nation’s capital. He wanted to reverse the adage long applied to the Senators: “First in war, first in peace, last in the American League.” The Senators had strung together three consecutive 90-win seasons. But it was not enough to wrest the pennant away from the league’s powers, the Yankees and the Philadelphia Athletics.

Cronin felt that the acquisition of outfielders Goose Goslin and Fred Schulte from the St. Louis Browns and Sewell from Cleveland might be the right ingredients for a trip to first place. Of the Sewell trade, Cronin commented, “I can’t see where any of our rivals possess a trio of receivers (Sewell, Moe Berg, and Cliff Bolton) of such high class.”

The idea of going to the Senators appealed to Sewell as well. His relationship with the Indians’ manager, Roger Peckinpaugh, had soured, and he was looking for a fresh start. Cronin recognized Sewell’s ability behind the plate and asked his help with the pitching staff. “Luke, I don’t know anything about pitching. Tell me when you think a man begins to weaken, and when we should change pitchers,” Cronin said.

Sewell not only handled the pitching staff, he also contributed with his bat. Twice he registered five hits, each game a 12-inning affair that ended with a Senators victory. He hit .264, with a career high 61 RBIs. Said Yankees skipper Joe McCarthy after the season, “Nobody on the outside appreciates how much Joe Cronin owes to Luke Sewell. Last year the Senators suffered from the worst catching in the league. This year they had plenty of intelligence behind the bat. Sewell fooled me completely. I figured that he was nearly though last season.”

On May 31, 1933, the Nats trailed the Yankees by three games. But from June through August they posted a 58-25 record to turn that deficit into an 8½-game advantage. Then they coasted to their first pennant since 1925 with a record of 99-53-1.

In the World Series they faced the New York Giants, who were not exactly bowled over by the Senators’ record. The Giants won the World Series in five games, with Carl Hubbell claiming two of the Giants victories. Sewell was 3-for-17 in the Series, with one RBI.

For Sewell, the next season was a big letdown from 1933. An infected finger kept him out of action until mid-June. When he returned he was hit on the head by a pitched ball from Bump Hadley of St. Louis. When Sewell finally returned to the lineup, he had to leave again to be near Edna, who was recovering from appendicitis.

In a bit of irony, Sewell was dealt to St. Louis on January 19, 1935, for Hadley, then quickly sold to the Chicago White Sox. Sewell spent the next four seasons on Chicago’s South Side, starting the most games behind the plate for the team in 1935-1937. On August 31, 1935, he caught his second no-hitter, when Vern Kennedy blanked Cleveland, 5-0. That season was one of his finest at bat, as hit hit.285 and had a career-high 67 RBIs.

In 1937 Sewell caught his third no-hitter when Bill Dietrich blanked the Browns 8-0 at Comiskey Park. “It is my opinion that of the three (no-hit) games, I had the easiest job with Dietrich,” Sewell recalled later. “First of all, he had control. His fastball was on the inside corner for both right- and left-hand hitters. As a result, they were hitting the ball with the handle of their bats and easy fly balls followed. The Browns hit only two balls hard, (first baseman Zeke Bonura) grabbing line drives batted by Bill Knickerbocker and Sam West.”

In 1937 Sewell was picked for the All-Star Game for the first and only time, but did not get into the game as New York’s Bill Dickey caught all nine innings.

Sewell was sold to the Brooklyn Dodgers after the season, but was released on April 20, 1939, without getting into a game. Three days later he signed with his original team, joining the Indians as a backup catcher and coach on manager Oscar Vitt’s team.

In 1940 the Indians were in a three-team race for the pennant, along with the Yankees and Tigers. In June about a dozen players rebelled over their treatment by manager Vitt, citing his ridiculing and caustic criticism of the players. Demanding a change of managers, they became known as the Indians “Crybabies.” The players’ choice to replace Vitt was Sewell. But Luke was loyal to Vitt and squelched any talk of becoming the manager by denying that he was interested in the position. “As far as I know there is no job open,” was Sewell’s reply more on more than one occasion. Also, he wanted to separate himself from the players’ actions as far as possible, so that he would not be implicated in the players’ plotting, or be assumed to be behind it. In the end, Indians owner Alva Bradley backed his manager and Vitt was retained for the remainder of the year. The Indians finished in second place, one game behind Detroit.

Sewell was satisfied with his job in Cleveland. It was close to his home in Akron. He intended to leave baseball after the 1941 season to begin a career in the rubber industry. Then Bradley informed him that the St. Louis Browns owner, Don Barnes, wanted him to manage the Browns and had been granted permission to talk to him. “You’ve been in baseball for 20 years now. You owe it to yourself to go over and listen to them,” Bradley told him. Sewell was reluctant to meet with Barnes. Once his train got to St. Louis, Sewell purchased a plane ticket to return to Cleveland right after he met with Barnes. Part of his reluctance was that the Browns were annually a second-division team in the American League, if not dead last. The other was that managing the Browns had proved to be a graveyard for managers. But the Browns’ general manager, Bill DeWitt, was enthusiastic about Sewell. “He knows the American League,” Dewitt said. “He’s not coming in cold, to experiment or to find out about the hitters in the league. He has considerable experience with pitchers and if our pitching can be helped, our ballclub will be helped. He has had no managerial experience, but he has been a coach and has been on successful clubs in the major leagues.” And eventually Barnes and Sewell came to terms, and Luke replaced Fred Haney as manager on June 5, 1941. After the Browns started the year 15-29 under Haney, Sewell directed then to a 55-55 record the rest of the season.

But the Browns were still the Browns. Except for an occasional season when they finished in the first division, being part of a pennant race, much less a World Series, was a distant dream for their fans. In 1942 they finished in third place, winning 82 games. It was the Browns’ best record in 18 years. Much of the credit for their invigorated play was given to the new manager. “Luke knew how to handle men,” said second baseman Don Gutteridge. “He could do it better than anybody. He knew how to get the best out of everybody and do it really in a sneaky way. He would be managing you and you wouldn’t know it. Luke installed a winning attitude, and that made the difference on the ballclub.”

In 1943 the Browns, suffering like all other teams from the shortage of front-line players because of World War II, finished in sixth place, with a 72-80 record. Then in 1944, the Browns managed to put together a team that took the American League by storm, winning the team’s first and only pennant. “After winning nine in a row to start the season, we began to think we could win the pennant,” said first baseman George McQuinn. “We realized that Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams and the rest of the big stars were off in the service. We were just as good as anybody else.”

It wasn’t easy. In September it was still a four-team race. From the 15th to the 23rd the Browns won 10 and lost 3, led by Jack Kramer, who won three of the games. Still, on the 28th the Browns trailed the Detroit Tigers by one game. Detroit was hosting the Senators for the final four games of the season, while the Browns had a four-game set at home against New York. “I’d rather have our job in the last four days against Washington then the Browns task of facing the Yankees,” said Detroit manager Steve O’Neill.

But the Browns swept the Yankees while Detroit could only break even against the Senators, and the Browns won the pennant. Sewell was named Manager of the Year by The Sporting News.

In the World Series the Browns’ opponent was the team they shared Sportsman’s Park with, the St. Louis Cardinals. Unlike the Browns, the Cardinals had a rich history of winning, and had won multiple world championships. “(Cardinals manager Billy Southworth) has a mighty good team; they must be good to win over 100 games for the third straight season,” Sewell said. “But I think we can show them some pitching that may bother them.”

In a move to cut expenses during wartime, and to ease a housing shortage, Sewell and his family shared an apartment with Southworth at 3754 Lindell Boulevard. Since both teams shared Sportsman’s Park, neither team was at home at the same time. When the Browns went on the road, Edna and the couple’s daughters went home to Akron, and they would return to St. Louis when the Browns had a homestand. Since both families couldn’t share the apartment during the World Series, they flipped a coin. Sewell won the toss, and Southworth looked for a temporary residence.

In a surprise move, Sewell started Denny Galehouse in Game One. Galehouse had won only nine games during the season. The Browns won 2-1. The teams split the next two games. Then the Cardinals, behind Stan Musial, Marty Marion, and Walker Cooper and Mort Cooper, won three straight and the Series. The Browns’ offense could muster no better than a .182 batting average, scoring just two runs in the last three games. They set a Series record since broken by striking out 49 times.

The Browns slipped to third place in 1945, then started reeling in 1946, after front-line players started coming home from the war. Sewell felt that some of the Browns players were not playing up to their prewar capabilities. Dissension started to permeate the team. Sewell resigned in late August as the Browns sank to seventh place.

Sewell took an executive position with the Robbins Rubber Company in Akron. But he was lured back to baseball by Cincinnati Reds manager Bucky Walters. He joined Walters’ staff as pitching coach for the 1949 season. After a dismal season that found the Reds mired in seventh place, Walters was fired and Sewell led the team in the last three games of the season. After the season he was named manager. Reds President Warren Giles said, “Luke did an almost miraculous job as manager of the St. Louis Browns. He also did a fine job with the Reds as a coach. We know him as a well-educated, intelligent person with a fine background with successful experience. In addition, he has the advantage of knowing our club and our league.”

But there were no miracles in the Queen City. The Reds finish in sixth place in 1950 and 1951, falling short of 70 wins both seasons. Sewell was fired in late July of 1952 with the team 20 games under .500. He moved on to the minor leagues, taking the helm of the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. He led the Leafs to the league pennant in 1954, and was named the league’s Manager of the Year. He managed the Maple Leafs to second place in 1955, He managed the second-place Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League for part of 1956.

After retiring from baseball, Sewell became the owner of Seville Centrifugal Bronze Inc., a bronze castings firm. He retired in 1970. In 1973 he was elected to the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. An avid golfer, Sewell often set the goal of hitting at or below his age and he accomplished the feat many times each year. According to Golf Digest, Sewell was the oldest player at 74 to score a double eagle (two strokes below par) on a par-five hole.

Sewell died of colon cancer on May 14, 1987. His wife, Edna, had died in 1982.

Sources

Golenbock, Peter; The Spirit of St. Louis. (NewYork: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000).

Peterson, Richard: The St. Louis Baseball Reader. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006).

Mead, William B; Even the Browns. (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1978).

Armour, Mark; Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010).

The Sporting News

Cleveland Plain Dealer

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives Player File

http://www.baseball-reference.com/

1910 United States Census Bureau

Full Name

James Luther Sewell

Born

January 5, 1901 at Titus, AL (USA)

Died

May 14, 1987 at Akron, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.