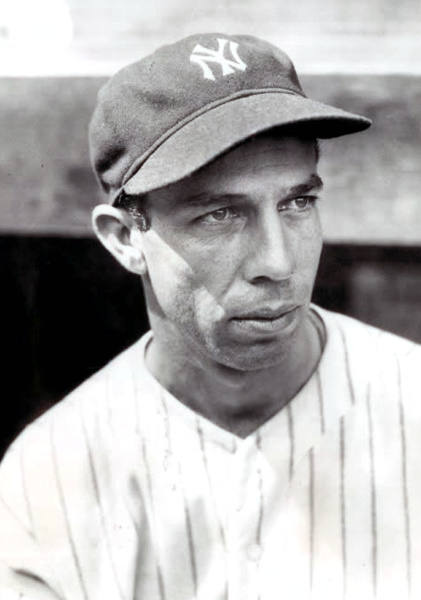

Lyn Lary

Babe Ruth called him “Broadway” because Lyn Lary loved the theater in New York, and Lary’s obituary in The Sporting News said he “tried his best to live up to the nickname the Babe hung on him. He was one of the best dressers in the majors and drove a big eight-cylinder car that had a silver nameplate on the door.”[1] And Lary married Mary Lawlor, who was part of the original 1925 cast in former Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee’s Broadway musical No, No, Nanette.

Babe Ruth called him “Broadway” because Lyn Lary loved the theater in New York, and Lary’s obituary in The Sporting News said he “tried his best to live up to the nickname the Babe hung on him. He was one of the best dressers in the majors and drove a big eight-cylinder car that had a silver nameplate on the door.”[1] And Lary married Mary Lawlor, who was part of the original 1925 cast in former Boston Red Sox owner Harry Frazee’s Broadway musical No, No, Nanette.

Lary was an infielder for 12 seasons who played for seven clubs in the major leagues from 1929 to 1940 and was part of a couple of the bigger money deals of the 1920s and 1930s, but “never quite lived up to baseball expectations,” despite posting a respectable .269 career batting average.[2] Lary stood an even 6 feet tall, with a playing weight of 165 pounds.

Lary was born in Armona, California, about 40 miles south of Fresno, on January 28, 1906, and was given the name Lynford Hobart Lary. He reported his heritage as Irish, and said the family name had originally been O’Leary.[3] His father, Clyde Lary, was a railroad agent and telegrapher. At the time of the 1910 US Census, Clyde and his wife, Rachel, lived in Kern, California, near the southern border of the Sequoia National Forest. Lyn may have been their only child. By 1920 Clyde had moved to Visalia, California, where he worked as an agent for the Southern Pacific Railroad. By 1930 he held the same position but had a new wife, Lois, a chiropractor.

There was some relocation for Lyn as he grew up; he went to elementary school in Tipton, Lindsey, and Visalia, and attended high school at Long Beach Poly and Visalia Union High. At Visalia, he played baseball, was an end and a halfback on the football team, and was a forward at basketball. He was also an honor student and sports editor of the school newspaper and active in drama. He planned to study dentistry, but economics pulled him in another direction. “I had ambitions to go to college, but I didn’t have the dough. I registered at the University of Southern California, but the day I was supposed to start my collegiate career I got an offer from the Hercules Oil nine, of Los Angeles, and as that was money in the pocket, I grabbed it. I had made some sort of reputation on the sandlots. From the Hercules team, I went to Oakland.”[4] Lary played some semipro ball in the San Joaquin Valley League. He also worked for a while as a stenographer.

During the spring of 1925 Lary spent some time working out with the Oakland Oaks. When their shortstop, Jake Flowers, was injured on June 25, the team worked him out before business manager Del Howard and president Cal Ewing, and promptly signed Lary to a contract and slotted him right into regular Pacific Coast League play. It took Lary a couple of years to develop as a hitter, his first couple of season averages being .257 in 1925 and .253 in 1926.

In 1927 Lary played a full 195 games (the PCL had much longer seasons than most leagues) and hit .293, with 12 triples and 12 home runs. Several teams were interested in him and his middle-infield partner, second baseman Jimmie Reese. The Sporting News observed, “Undoubtedly, they are the best pair on any minor-team in the country.” [5] The Oaks walked off with the pennant, 14½ games ahead of the second-place San Francisco Seals. Lary finished second to Lefty O’Doul in voting for the league MVP.

At some point, first announced on January 9, 1928, but possibly having happened as early as August 12, 1927, the New York Yankees purchased the contracts of Lary and Reese for $125,000 cash, though they agreed to leave both with the Oaks to play out the season – and all of 1928 as well. Reportedly, one of the conditions of the sale was that the two players be allowed to report to the Yankees in the spring of 1929 and that the Chicago Cubs had offered as much as $150,000 but lost out because they wanted the two infielders immediately.[6] It was widely understood that most of the money was for Lary. He was one of the costliest rookies of his era. The money, of course, went to Oakland. Lary himself was reportedly offered a salary of $8,000.

A January 12, 1928, feature in The Sporting News presented details of the Lary/Reese purchase in an article headlined “Keystone Kids – They Go As Siamese Twins.”

Lary upped his Oaks average in 1928, to .314. Even so, New York General Manager Ed Barrow later considered it to be one of the worst deals he’d ever made. After recounting some of his better deals, he said, “But I also made some terrible ones. How about paying $100,000 for Lyn Lary and $25,000 more for Jimmy Reese?”[7]

The Yankees had been so well-stocked with star players that they could afford to wait until 1929. When he had the opportunity, Lary made a mark in his game at Yankee Stadium. He made his debut in Detroit on May 11, taking over for Tony Lazzeri during a blowout loss. A week later Lary played both halves of a doubleheader at home against the visiting Boston Red Sox, going 1-for-4 in the first game (with his first big-league RBI) and 1-for-2 in the second game, with his first home run.

Lary was competing for playing time with Leo Durocher at shortstop. He had started a month later, but except for some downtime in July, he played fairly regularly the rest of the season. Both shortstops were right-handed hitters, but Lary seemed to have a hotter bat and in 80 games (Durocher appeared in 106), he hit .309 to Durocher’s .246. In February 1930 Durocher’s contract was sold to the Cincinnati Reds.

Lary became the Yankees’ regular shortstop in 1930, appearing in 117 games and hitting at a .289 pace. A fractured thumb on June 20 cost him two weeks. He drove in 52 runs and scored 93. He still had work to do in his fielding, next-to-worst in the league at his position with a .940 fielding percentage. He remained subpar much of his career, but hit significantly better than most shortstops of the day. There were stories early on about how frustrated manager Miller Huggins could be with Lary’s fielding, and one account had a teammate slugging Lary in the jaw after a particularly egregious failure had Huggins storming out onto the field to remove Lary from the game.[8] Mental errors seemed to be the problem as much as anything; he also received some criticism for “heedless base-running.”[9] The New York World-Telegram’s Dan Daniel characterized it as a “‘blind spot’ in his mentality. Sometimes, as he fielded the ball in a tight situation, his mind would go blank. He would hold the ball just too long and suddenly haul off with a wild heave.”[10]

In 1931 Lary appeared in every one of New York’s 155 games – including two tie games (as, of course, had Lou Gehrig). He hit .280 for new manager Joe McCarthy and drove in 107 runs, scoring an even 100, ten of them on home runs he’d hit. His grand slam and six RBIs against the Chicago White Sox on May 9 represented his best single game. Overall, the season home-run and RBI marks were the best of his career. Early in the year came another mental lapse. It came in the top of the ninth, with two outs and New York down by two runs. Lefty Gomez told the story several years later: “Lou Gehrig was fighting Babe Ruth for the home run championship. I think they finished in a tie, 49 to 49. Lary was on base. Gehrig belted one of his super-specials over the right-field wall, and jogged around, for the ball game. We kept our eyes on Gehrig. We never paid any attention to Lary. He touched third, and then streaked for the dugout, where he took a drink of water. … [Gehrig rounded the bases and crossed the plate – where he was ruled out, for passing Lary on the basepaths]. We did not realize that Lary had failed to score, and that the Gehrig home run was nullified. Lary could not explain the lapse.”[11] The date was earlier in the season than Gomez had made it seem; it was on April 26 in Washington. Lary did say that the ball had landed in the seats and then popped back onto the field and that he thought that Gehrig had flied out. The game ended without either run scoring, and the Yankees lost, 9-7. Gehrig was credited with a triple.

In the middle of the 1931 season Lary accomplished something else many men dream about: He married the movie star he’d become infatuated with on the screen. While still in Oakland at the end of 1929, he’d taken in the film Good News and was wowed by actress Mary Lawlor. He and a friend stayed to watch the film a second time, and to hear her sing the song “Lucky In Love.” The song became very popular, and melody stuck with him, as did the well-known words from another song in the film: “Love can come to everyone, the best things in life are free.” In 1930 he saw her in another film, Shooting Straight. Apparently, he saw the film many times in between games. But Lawlor had taken a break from Hollywood productions and in April 1931 had come to New York, where she opened at Chanin’s 46th Street Theatre in the musical comedy You Said It. By coincidence David Marks, a friend of Lary’s, had invited him to a performance and when Lary spotted Lawlor on stage, he asked Marks if he could introduce them. He didn’t wait until after the show, but was introduced during intermission. Lawlor wasn’t impressed that he played major-league baseball. She’d never been to a game and only had a vague idea that Babe Ruth was a baseball player. Lary mumbled a few words, but the next morning left a pair of tickets to that day’s game for her. She was busy and never showed.

David Marks was active on Lary’s behalf and arranged a dinner and dancing date between them at the New Lido. The orchestra leader spotted Lawlor and both Lyn and Mary were dancing to selections from Good News. Gardenias and a charm bracelet followed, and a whirlwind romance – interrupted by road trips. Lary proposed by telephone, and Mary accepted. They planned to marry on a Yankees offday but it was the 13th of July, and he didn’t want to be unlucky in love, so they were held off at the last minute – but while passing through Times Square they saw the news flash on the Times Square Building: “Broadway’s Mary Lawlor Wed to Yankee Shortstop.”[12] The next morning they made it official. Then Lary had to rush to the ballpark. He was 3-for-5 with a home run and four RBIs in the first game against the Indians. He was 0-for-3 but batted in another run in the second game.

Lary did miss some games in 1932, with Frankie Crosetti playing shortstop in 84 games and Lary in just 80. Even before the season had begun, there was some expectation that Crosetti might displace Lary at short.[13] The Yankees had finished in second place in 1931, and Lary– who impressed McCarthy as a “game fighter” – was the early choice for shortstop.[14] Neither player had strong offensive seasons; Crosetti hit .241 and Lary hit .232. In 1933 McCarthy let the two (plus Billy Werber) fight it out to see who would be shortstop. Crosetti got most of the work and hit .253 in 136 games, while Lary appeared in only 52, playing third base in 28 of them, and batting .220.

In July, the Larys added a family member in Lynford Lawlor Lary. Babe Ruth was the godfather.[15]

Lary’s name came up in trade rumors during the offseason; he was on the block, for sure. The Tigers were interested in him to play third base. But he also had value as backup insurance for Crosetti, and the Yankees still held out hope he’d begin to play more to what they saw as his greater potential. McCarthy used Lary in only two games in 1934, as a pinch-runner on April 30, when he scored a run, and on May 10, when he walked in his only plate appearance of the year for the Yankees. On May 15 Lary was traded to the Boston Red Sox for Freddie Muller and $20,000 of Tom Yawkey’s cash. He was leaving the very successful Yankees to a Red Sox team that had barely been out of last place for more than ten years, but such was his timing even with the Ruth and Gehrig Yankees that he never once appeared in postseason play.

Though he didn’t wield a powerful bat, there were hopes that Lary might blossom in Boston. He was, after all, only 28. The Boston Post’s Paul Shannon wrote, “The prospect of playing regularly may inspire a veteran, forced to warm the Yankee bench, to show up better than he ever did with Joe McCarthy’s team.”[16] A month later, Shannon said, “Lyn Lary, worn out by warming the New York bench for several seasons, never regarded as a strong hitter … proves to be just the man that the Red Sox were looking for. In the line-up regularly, he works beautifully as a running mate for Bill Werber, and any drive that gets by either of these alert infielders in a genuine hit.”[17]

For Boston, Lary hit .241 but drew a good number of bases on balls (66) and had an on-base percentage of .344 (over the full course of his career he had a .369 OBP). And he served as fodder for one of the more momentous trades in team history – to provide the Washington Senators with a shortstop in exchange for Joe Cronin. Washington also pocketed perhaps $250,000 – at the time the largest amount ever spent for a player. Consummated on October 26, this was the second big-money deal in Lary’s career, though in this case Cronin was the main man. Lary was not just a throw-in, though. Paul Shannon rated him highly: “[T]he Red Sox gave the Senators a man who practically made the Red Sox infield in 1934. While Lary never rated as a hard hitter, his fine work at short atoned for any weakness with the bat.”[18] His .965 fielding percentage led all shortstops in the American League.

With the Senators, Lary faced some unexpected competition from Ossie Bluege, but won the shortstop job – at first. But with Lary batting only .194 after 39 games, the Senators handed the job to Bluege and traded Lary to the St. Louis Browns on June 29 for backup shortstop Alan Strange. Playing under manager Rogers Hornsby, Lary hit .288 in the 93 games he played as a regular for the Browns. And in 1936 he enjoyed the best season of his career: He hit .289, with a .404 on-base percentage, and scored 112 runs. He led the league in stolen bases with 37. In mid-September Hornsby said he rated Lary the best shortstop in the league.[19] Early in 1936 Hornsby said, “I credit his showing to the fact that he regained his confidence. Lary is a player who must be in the game regularly.”[20]

After Lary died, Bob Feller recalled that in his first career start, Lary had been the first strikeout he recorded.

Hornsby had gotten another good season out of Lary, but there were apparently some points of friction, and with the Browns under new ownership, a January 17, 1937, swap sent Lary, Julius Solters, and Ivy Andrews to Cleveland for Joe Vosmik, Bill Knickerbocker, and Oral Hildebrand. Solters seems to have had some of the same issues with Hornsby’s style as did Lary. Initial fan reaction to the trade was positive in St. Louis, but not so in Cleveland, mainly because Vosmik had been a fan favorite.[21] Cleveland sportswriter Ed Bang spoke well of the new Tribe shortstop: “Lary not only is a better defensive player than Knick, but his aggressiveness may fire a club that long has been lacking in spirit.”[22]

The Indians couldn’t have been disappointed: Lary’s production was almost precisely the same as in 1936. Going 3-for-5 on Opening Day didn’t hurt. He hit over .300 most of the year until September but finished at .290, scored 110 runs and drove in 77 (25 more RBIs than the year before), though he stole fewer bases. He was considered an untouchable for 1938, not available in any trade talks.

Lary regressed in pretty much every category in 1938, dropping to .268 in average, and though his fielding percentage was second in the league, there was indication that his range wasn’t the same. Ed McAuley wrote, “Toward the end of the season, Lary was no Jesse Owens at moving to his left.”[23] General Manager Cy Slapnicka of the Indians fielded at least four offers for Lary, however. He was hoping Lary would bounce back from a disappointing year, but there was a strong sense that he was more reconciled than hopeful. Lary was also a bit of a pain; ever since his first season in New York, he was almost always one of the last players to sign his contract, either holding out or flirting with holdout status.

As with New York five years earlier, Lary was barely used for the first couple of weeks of the 1939 season, appearing in just two games without a hit in either of his two plate appearances. The Indians sold his contract to the Brooklyn Dodgers on May 3. Side-by-side stories in May 11 Sporting News speculated that he’d been sold for the waiver price, or below the waiver price. It’s not clear Lary even provided that much value for Brooklyn. He collected 46 plate appearances in 29 games and hit just .161 with a total of one run batted in. And he didn’t finish the year with the Dodgers; they sold his contract to the St. Louis Cardinals on August 14, via waivers.

With St. Louis Lary plugged a hole at shortstop, but didn’t hit that much better, batting .187 in 96 at-bats over 34 games. He drove in nine runs. There was one time he lost a double in Boston. It was the top of the ninth, against the Bees on August 27. But it was the second game of a Sunday doubleheader and Boston’s Sunday baseball law called for a 6:00 P.M. halt. The game was called, and the score reverted to where it stood through eight innings. The Cardinals still won, 6-5, and Lary had driven in one of the runs, but his double was wiped from the books.

Three days after the season ended, Lyn Lary and Mary Lawlor Lary remarried in Miami. They had divorced in January due to what her father called “a clash of professional temperaments.”[24]

In 1940 Lary didn’t get to play in even one early -season Cardinals game before he was unconditionally released on April 23. Three days later, he signed as a free agent with the other St. Louis team, working again for the Browns. His career just petered out. He appeared in 27 games for the Browns, batting .056 in 61 plate appearances. He drove in three runs and scored five. He played his last major-league game on August 7 and he was released nine days later.

Lary wasn’t ready to give up. He worked out in Miami with the New York Giants in February 1941. If he played for them, he’d tie the record at the time for playing for the most major-league clubs. He didn’t make it, and in March signed with the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. He hit .245 in 42 games, but was released on May 15. On July 26 the Knoxville Smokies took him on, and he hit hitting an almost identical .244, then was released on August 20.

During the offseason, Lary put his name forward as a candidate to manage the Portland Beavers of the PCL. He didn’t get the position, and signed in March with the Montreal Royals. He never played with Montreal, winding up with the Buffalo Bisons, and batting .196. He was released on May 19, then rejoined the team as a coach the next day.

After baseball Lary went to work in the aircraft industry, during World War II in the dispatch department of Bell Aircraft in Buffalo and later with North American Aviation in Downey, California, where he and Mary made their home. His work was specifically as a purchasing expediter and buyer for Autonetics, a division of North American Aviation. He suffered diabetes for more than 20 years and ultimately died of heart failure on January 9, 1973, survived by his wife and their son.

November 17, 2011

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Lary’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

[1] The Sporting News, January 27, 1973

[2] Ibid.

[3] Unattributed 1929 news clipping by Theold Underwood found in Lary’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

[4] Ibid. Oddly, every other story over the years referred to the more likely scenario of Lary being accepted at the University of California at Berkeley. One wonders if the quotation attributed to him may have been incorrect.

[5] The Sporting News, November 3, 1927. Offers had been fielded as early as mid-1926. See, for instance, the Los Angeles Times of July 25, 1926.

[6] New York Times, January 5, 1928

[7] The Sporting News, January 22, 1947

[8] The Sporting News, September 12, 1929

[9] The Sporting News, March 3, 1932

[10] New York World-Telegram, February 18, 1941

[11] The Sporting News, June 10, 1937. Gomez was wrong about the number of home runs; both Ruth and Gehrig finished the season with 46. It was the year that Gehrig drove in 185 runs.

[12] Details of Lary’s courtship and wedding are from a lengthy feature in the Cleveland Press, August 8, 1938. The New York Times account of the actual wedding ran on July 15, 1931 and reported that a spiking Lary had suffered with Oakland in 1928 had resulted in three of his teammates becoming married to nurses they met while visiting him! Among the trio was Louis McEvoy, who was best man at Lary’s wedding. The other two ballplayers were Johnny Vergez and Howard Craghead.

[13] The Sporting News, November 26 and December 3, 1931. Crosetti had cost the Yankees $75,000 and there was some thinking that Lary would be tried at third base.

[14] The Sporting News, June 23, 1932

[15] Annotation added to survey completed for Prof. Marshall Smelser and found in Lary’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

[16] The Sporting News, May 24, 1934

[17] The Sporting News, June 28, 1934

[18] The Sporting News, November 1, 1934

[19] The Sporting News, September 19, 1934

[20] The Sporting News, January 30, 1936

[21] The Sporting News, January 21, 1937

[22] The Sporting News, January 28, 1937

[23] The Sporting News, January 19, 1939

[24] Washington Post, October 5, 1939

Full Name

Lynford Hobart Lary

Born

January 28, 1906 at Armona, CA (USA)

Died

January 9, 1973 at Downey, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.