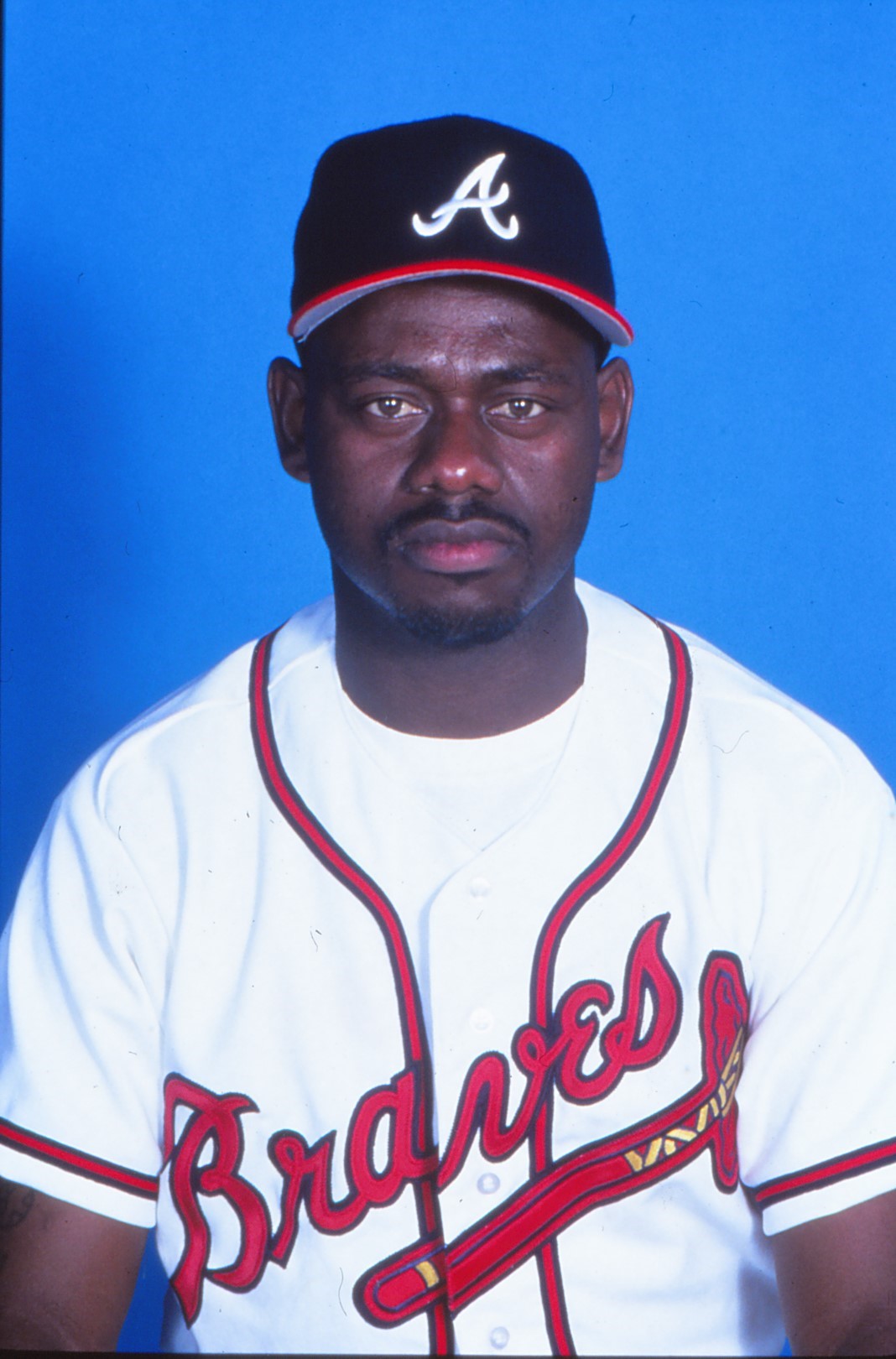

Marquis Grissom

On a chilly October night, Marquis Grissom gracefully glided to his right from his position in center field at Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium and gloved the final out of the 1995 World Series. After three tries, the Atlanta Braves were the champions of professional baseball. The man who gloved that final out was the only native Atlantan on the team, having grown up 12 miles south of the Braves home field. Marquis was a team player from the beginning. He had seven brothers and seven sisters and their parents, Marion and Julia Grissom, expected everyone to pitch in. Marquis remembers stacking firewood on the porch and drawing buckets of water from the well as he did his part.

On a chilly October night, Marquis Grissom gracefully glided to his right from his position in center field at Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium and gloved the final out of the 1995 World Series. After three tries, the Atlanta Braves were the champions of professional baseball. The man who gloved that final out was the only native Atlantan on the team, having grown up 12 miles south of the Braves home field. Marquis was a team player from the beginning. He had seven brothers and seven sisters and their parents, Marion and Julia Grissom, expected everyone to pitch in. Marquis remembers stacking firewood on the porch and drawing buckets of water from the well as he did his part.

The story of how Grissom began his baseball career is worthy of an HBO special. He’s about 10 years old and playing stickball in the street in front of his house when a big Cadillac makes its way through the Red Oak neighborhood of College Park, Georgia. It is moving slowly and causing a delay of the ballgame as the kids leave the street hollering at the driver to move on so they can play. Several decide to teach the driver a lesson and hurl rocks toward the car as it moves up the hill. Marquis waits until the car turns behind a house and he lets fly. The car stops and turns around as some of the kids scatter. The driver gets out of his car and wants to know who threw that last rock. Everyone points at Marquis. He confesses and the man asks, “Where do you live, son?” Marquis points to the house across the street and the man says, “Follow me.” When they get inside, the man introduces himself as T.J. Wilson, an off-duty Atlanta policeman, and says, “Your son just hit my car with a rock but if you will allow him to play on my ball team, I will call it even.” Marquis is stunned and then relieved when his mama says, “OK as long as he has time to do his homework and chores, you can have him.”1

Marion Grissom worked at the Ford plant in Atlanta. One day he parked a new Mercury Marquis and said to himself, “Doggone, that sounds good — Marquis.” It was April 17, 1967, and he put it down on the birth certificate of his 14th child, Marquis Deon Grissom.2 While his father worked at the Ford plant, his mother tended the family garden, took care of the house, and did her best to instill discipline in a houseful of kids.

“I wanted two boys and two girls,” Julia Grissom told a reporter from the Atlanta Constitution. “But things just kept happening.”3 Marquis’ dad built their house with his own hands with help from some of the older children. “It was a big house. It had seven rooms and three bathrooms, but we could have used more,” Marquis said of growing up just south of the Atlanta airport.4 He played football, baseball, and basketball and ran track at Lakeshore High School. Marquis earned his nickname “Grip” because he always had a ball in his hand and he could easily palm a basketball. He loved sports and knew that participating in sports would keep him off the streets and out of trouble. His mother “never gave me any breathing room.” She made sure Marquis did right.5

Marquis figured he would end up playing football because it was his favorite sport. “I was a running back and loved the game even though my mother didn’t want me to play –afraid I would get hurt.”6 He had offers of college scholarships as a senior but he was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds and offered a $17,000 bonus as a pitcher. “I wanted the money but my mom and dad and high-school coach discussed it and put it to a vote. I voted for the money but everyone else voted for me to go to college. I was outvoted.”7 Marquis went to Florida A&M in Tallahassee on a baseball scholarship.

Grissom batted .448, hit 12 home runs, and led the nation’s collegians in triples, and after his sophomore year he was drafted again, this time by the Montreal Expos, who offered him $48,000. He was 21 years old and ready to go, this time without a vote. Everyone knew he was ready for pro ball.

Grissom began his pro career with the Jamestown (New York) Expos. Perhaps because it was his first time north of the Mason-Dixon Line or just the jitters, he got off to a terrible start and was ready to pack his bags and head south. “I called my girlfriend and told her I was taking one more road trip and if I didn’t start hitting, I was going back to college.”8 That call must have been the magic because the next day he went 4-for-5 and everything changed. He ran off a string of multi-hit games and finished the season with a .323 average. The next season was with the Double-A Jacksonville (Florida) Expos and the same thing happened. After a slow start he got his average up to .299 with 24 stolen bases and was promoted to Triple-A Indianapolis. He was on the fast track to the major leagues.

After only a year and a half in the minors, Grissom’s major-league debut occurred on August 22, 1989, at Stade Olympique in Montreal. Facing the perennial All-Star Fernando Valenzuela, he popped out to the catcher leading off the game against the LA Dodgers. He grounded to third in his next at-bat and then in the bottom of the fifth got his first major-league hit, a sharp single to center scoring a runner. The Expos went on to win the game, 4-2. Grissom finished the season with a .257 BA, and .360 OBP.

During the 1990 season people began to notice the rookie outfielder, who started 68 games for the Expos, at all three outfield positions. He batted .257 with an on-base percentage of .320 and stole 22 bases while being caught stealing only twice. His fielding was superb. He made only two errors and his strong arm (remember, he was drafted as a pitcher) resulted in four assists. The Expos finished in third place with only one regular position player (Tim Wallach) over 30 years old. Grissom placed seventh in Rookie of the Year balloting.

The next season Grissom became the Expos’ starting center fielder. He batted .267 with an on-base percentage of .310. He led all major leaguers with 76 stolen bases. The team fell to sixth place but with a nucleus of young talent like Grissom (24), Larry Walker (24), and Delino DeShields (22), along with veterans Tim Wallach (33) and Andres Galarraga (30), it was not surprising that Expos fans were getting excited.

Grissom became a leader of the ’92 Expos team. After GM Dan Duquette replaced manager Tom Runnells with Felipe Alou, the Expos challenged the Pirates for the National League East title. Grissom batted .276 with an OBP of .322 and again led all major leaguers with 78 stolen bases. He placed ninth in balloting for the National League MVP. He was a star on the rise. He was featured in a Sports Illustrated story in the fall as the Expos were attempting to overtake the Pirates. Grissom credited new manager Alou with helping change the atmosphere in the clubhouse. “He said if we lost 10 in a row, he might be fired, but none of us would lose our jobs. … It’s much nicer now. You make a mistake, you know it’s a mistake. No one has to tell you … that’s how Felipe treats us.”9 Grissom also had good things to say about coach Tommy Harper. “He’s like a second father to me. We talk about everything, not just baseball. I learn things from him every day about stealing bases.”10

After his baseball career was over, Grissom said that Harper also taught him how to be a better center fielder. Harper suggested that he play a shallow center field because with his speed he could catch up to balls hit deep and turn shallow fly balls into outs much as Willie Mays did.11 Grissom also paid tribute to Bobby Cox, whom he called the best manager ever in the major leagues.

It all came together for Grissom in the 1993 and 1994 seasons but it did not begin well. He lost a bitter salary arbitration battle with the Expos in February before the ’93 season began. He felt a “lack of respect … words were said I’ll never forget.”12 Before the hearing Grissom had imagined spending his whole career with the Expos. “I love playing with the Expos and I love the fans in Montreal. I was thinking about wanting to play all my baseball there,” he said.13 He loved his teammates and believed they had the talent to win it all. He was happy with manager Felipe Alou and was enjoying his success. He did not let the bitter dispute with management affect his attitude toward the game.

At the All-Star break, Grissom had 93 hits, 53 RBIs, and 19 stolen bases. He was named to the All-Star team for the first time and was the leadoff batter for the National League. The Expos battled the Phillies all year for first place in the East. At the end, they came in second with a record of 94 wins and 68 loses. No small accomplishment for one of the youngest teams in the major leagues with the second lowest payroll. Grissom ended the year with the highest WAR on the team. He won his first Gold Glove award and placed eighth in MVP balloting.

The ’94 season began with high hopes for the Expos, still one of the youngest teams but loaded with talent. Manager Felipe Alou had the highest respect from his players and was voted the NL Manager of the Year. Had it not been for the players strike in August, it is likely the Expos would have won the National League East championship and perhaps made it to their first World Series. When the strike began, the Expos had a six-game lead over the second-place Atlanta Braves. Grissom was batting .288 with a .344 on-base percentage, 11 home runs, and 36 stolen bases. He made his second All-Star team and homered off Randy Johnson, helping lead the National League to a win. At the end of the season he received his second Gold Glove award.

The ’94 postseason playoffs and World Series were canceled with the Expos having the best record in baseball. But there was trouble in Montreal as the team owners began to express doubts that they could afford to keep the team together. The newspapers called it a “Fire Sale.”14 On April 6, 1995, the Expos traded Grissom to the Atlanta Braves after six years with the club that drafted him and saw him become a multitalented star. The Expos received three players in exchange: outfielders Roberto Kelly and Tony Tarasco, and minor-league pitcher Esteban Yan. One newspaper headline in Atlanta read, “Trade Should Put Braves in World Series.”15 These prophetic words were followed with “[T]his deal will make the Braves infinitely more fun to watch and you can argue he is the most exciting player in the league, the best lead-off hitter, the best defensive center fielder.”16 In addition to being a star, Grissom was an Atlanta native and now a hometown player.

Grissom did not fail to succeed. Along with starters Fred McGriff, David Justice, Chipper Jones, Ryan Klesko, and Javy Lopez, he gave the Braves an intimidating batting order. With these bats and a starting rotation that featured future Hall of Famers Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz, the Braves were destined to again make it deep into the postseason. Grissom had a solid year as the leadoff hitter, batting just .258 but scoring 80 runs. He earned his third straight Gold Glove Award. But it was in the postseason that he became a hero. He batted .524 in the Division Series with three home runs, two doubles, four RBIs, and two stolen bases. He was 5-for-5 in the final game as the Braves dispatched the Rockies in four games.

The Braves easily swept the Reds in the Championship Series and Grissom carried a .400 postseason average heading into the World Series. He was a major contributor to the Braves’ triumph over Cleveland. He went 9-for-25 (.360), scored three runs, and stole three bases. It was only fitting that the Atlanta native squeezed his mitt on a lazy fly ball to center field for the final out to secure the first championship for the Atlanta Braves.

John Smoltz said after the Braves victory: “He’s one of my biggest weapons. … If you give him any hangtime at all, he’ll catch it. He plays shallow, he can run back on the ball, he has a great arm — put that together with his offense, I think he’s the best center fielder in the National League.”17

The Braves were delighted with their 1995 season and the play of their new center fielder/leadoff man. No one was surprised when the Braves offered him a four-year contract worth $19.2 million. Grissom signed the contract and told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “I’m speechless, we just won the World Series, I’m living at home. It’s like: what can happen next?”18

What happened next was his best year. Grissom set career highs in home runs (23), triples (10), and batting average (.308). He scored 106 runs and had 207 hits, 74 RBIs, and 328 total bases. He made only one error and had 10 outfield assists. He received his fourth Gold Glove Award and helped the Braves repeat as National League champions. In the World Series they fell to the Yankees in six games. Toward the end of the ’96 season a sportswriter said Grissom “brings to the ballpark a belief in work being its own reward and great good sense.”19

In a move that shocked Braves fans and players, Grissom and David Justice were traded to the Cleveland Indians for Kenny Lofton and Alan Embree before the ’97 season. Coming off his best season, Grissom did his best to put on a happy face but he was clearly disappointed, as were many teammates. Chipper Jones summed up the clubhouse sentiment: “Everybody’s bummed.”20 Fans questioned why anyone would break up a team that had made it to the World Series for the past two years. Grissom’s family could not hold back tears. His wife, Tia, tearfully responded to a reporter’s question, “He told me he was traded and I said, ‘Come on, quit joking around,’ but he said he would never joke around about that. He was upset. He was trying to not be upset, but he was.”21

The Braves front office made the case that the franchise was confident the trade would not weaken the club. The team had two young outfielders, Andruw Jones and Jermaine Dye, who needed major-league playing time, and still had Ryan Klesko. Lofton was a proven leadoff hitter and Gold Glove center fielder.

Grissom was welcomed to Cleveland and although his ’97 regular season was not his best (.262, 22 stolen bases), he shined in the postseason and helped lead the Indians to the World Series, his third Series in a row. Grissom was the MVP of the ALCS, in which he hit a three-run homer in Game Two and stole home in the 12th inning to win Game Three in Cleveland. The Indians lost to the surprising Florida Marlins in the World Series, in which Grissom completed a 15-game Series hitting streak. (The only player to exceed this record was Hank Bauer of the Yankees.)

After one season in Cleveland, the Indians re-signed Kenny Lofton and traded Grissom to the Milwaukee Brewers. He struggled during a three-year stint with the Brewers as his speed and hitting eye declined. He was the regular center fielder but the Brewers were a mediocre team in a strong Central Division.

The Brewers traded Grissom to the Los Angeles Dodgers before the 2001 season. Dodgers general manager Kevin Malone was familiar with Grissom from his days in Montreal. “I’ve known Marquis since 1988, and this is not only a championship player, he’s a championship person,” Malone said. “He’s a gamer. He wants to win. He’s a competitor. What he will bring to this team is a tremendous attitude and tremendous makeup.”22 Grissom spent two years with the Dodgers but in his second season played only 102 games as he tried to overcome hamstring problems.

But good fortune seemed to follow Grissom. The San Francisco Giants hired Felipe Alou as their manager. It was no surprise that the team wanted to get his former center fielder back. Grissom, a free agent, signed with the Giants. He was excited: “At this point in my career, I’m just glad to have the opportunity to come back and be a starter again.”23 He did not disappoint. He batted .300, hit 20 home runs, stole 11 bases, and had 79 RBIs. Near the end of the regular season, the Giants gave Grissom their highest honor, the Willie Mac award. Players, coaches, and training staff vote on the award, which honors the team’s most inspirational player. In the words of Willie McCovey, after whom the award is named, “That’s something isn’t it, he had stretches last year when he got hot, and I could not understand why he was out of the Dodgers lineup.”24

The Giants entered the postseason with high hopes but were eliminated in the first round by the Florida Marlins, three games to one.

As the starting center fielder in 2004 Grissom’s batting average dipped to .279 but he knocked in 90 runs and scored 78. The Giants made a run at the National League West title but lost by two games to the Dodgers. They were in and out of first place all season but failed to make the playoffs.

The Giants put together a veteran lineup for the 2005 season but injuries to key players including Barry Bonds and Grissom contributed to a losing season. Grissom played in only 44 games and batted a career-worst .212 with only one stolen base. He considered hanging up his spikes but felt he had enough left to give it another try. The Chicago Cubs invited him to spring training in 2006. It became obvious that he was not going to make the major-league roster so he called it quits. Just before the season opened, Grissom said, “I came into spring training … to see if I could go out and play baseball again for another year. It didn’t work out.”25

Only 10 major leaguers have retired with 2,000 hits, 200 home runs, and 400 stolen bases: Craig Biggio, Roberto Alomar, Barry Bonds, Rickey Henderson, Paul Molitor, Joe Morgan, Johnny Damon, Bobby Abreu, Jimmy Rollins, and Marquis Grissom. All are in the Hall of Fame except Bonds, Abreu, Damon, Rollins, and Grissom. Bonds would easily be in the Hall if it were not for being tainted with the PED controversy. In 2011, his first year of eligibility, Grissom received four votes and was dropped from the ballot. His legacy is a powerful work ethic and an enduring love for the game.

After retiring as a player, Grissom started the Marquis Grissom Baseball Association. The MGBA is more than a training ground for young ballplayers, it is focused on being a tutorial program, helping Atlanta-area youngsters with math and language skills and preparing them for taking college entrance exams.26 He said this is his way of paying back for the coaches he had as a young man. “I got so much out of my youth coaches and what they taught me at an early age really made a difference. … I didn’t have a ride to practice … equipment, not much at all, but those coaches were there for me … and I wanted to do the same thing. … [I]t was time to give back.”27 As of 2019, 1,600 students had participated in the MGBA program and a high percentage of them have received college scholarships.28

In 2009 Grissom was lured back into the major leagues by Stan Kasten, who as president of the Braves was primarily responsible for bringing him to the team. Kasten recalled Grissom’s first day with the Braves when he observed him giving teammate Tony Graffanino tips on how to take leads when preparing to steal a base. “I thought, wow, that’s really impressive. That’s a future coach.”29 It took Kasten two years to persuade him to come work as the first-base coach for the Washington Nationals. One year was enough. Grissom missed working with his baseball association in Atlanta.

One of the first things Grissom did with the money he made as a professional ballplayer was to build his parents a house on land his dad had purchased a few years earlier. He did not stop there. As his salary and stardom increased, he began buying houses for his seven brothers and seven sisters. He talked to them about how to use the money saved on house payments to plan for their children’s education. He bought himself a nice 11,000-square-feet house and several luxury cars because that’s what ballplayers did. “I look at that stuff now — I didn’t overdo it, but even the stuff I got, I don’t need it. I look back now, it don’t mean nothing,” he said.30

Last revised: February 15, 2021

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball Digest (December 1993), and “The Art of Excellence,” an interview with Marquis Grissom with Glenn Zweig on You Tube, at youtube.com/watch?v=oCqELgJ8C_M.

Notes

1 Greg McMichael, “Behind the Braves,” podcast, YouTube February 2, 2019. youtube.com/watch?v=wnNdDHEW45U&t=423s.

2 Dave Kindred, “The Grissom Trail: From a Pasture to Center Field,” Atlanta Constitution, October 15, 1995: 47.

3 Kindred, “The Grissom Trail.”

4 Leigh Montville, “We Are Family,” Sports Illustrated, September 28, 1992: 38-41.

5 Kindred, “The Grissom Trail.”

6 Montville.

7 Montville.

8 Montville.

9 Montville.

10 Montville.

11 McMichael podcast February 2019.

12 Ian McDonald, “Bitter Grissom Planning Post Expos Career,” The Gazette (Montreal), February 26, 1993: 43.

13 McDonald.

14 Jeff Blair, “Fire Sale II: Grissom to Braves,” The Gazette, April 7, 1995: 39.

15 Tim Tucker, “Trade Should Put Braves in World Series,” Atlanta Constitution, April 7, 1995: 44.

16 Tucker.

17 Carroll Rogers, “A Brave New World,” The Gazette, October 22, 1995: 27.

18 “Baseball Notes,” The Gazette, November 12, 1995: 22.

19 Dave Kindred, “The Secret of Grissom Plain and Simple: Work,” Atlanta Constitution, September 22, 1996: 53.

20 Steve Hummer, “In a Cold Deal, Sentimentality Not Thrown In,” Atlanta Constitution, March 26, 1997: 43.

21 I.J. Rosenberg, “Grissom’s Wife ‘Very Shocked,’” Atlanta Constitution, March 26, 1997: 98.

22 Jason Reid, “Dodgers Send White to Brewers,” Los Angeles Times, March 26, 2001: 149.

23 Janie McCauley, “Work Makes Grissom Go,” San Francisco Examiner, March 4, 2003: 24.

24 Brian Murphy, “Giants Notebook: Grissom Wins ‘Willie Mac’ Award,” SFGate.com, September 27, 2003. sfgate.com/sports/article/GIANTS-NOTEBOOK-Grissom-wins-Willie-Mac-Award-2585941.php.

25 Associated Press, “Ex-Braves Grissom Calls it Quits,” Atlanta Constitution, March 39, 2006: D4.

26 I.J. Rosenberg, “Whatever Happened to Marquis Grissom,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 2, 2015. ajc.com/sports/baseball/whatever-happened-marquis-grissom/FufBZxFQwvo5yzh5WcYqMP/.

27 Rosenberg.

29 Chico Harlan, “Washington Nationals Coach Marquis Grissom Changes Lives Through his Baseball Association,” Washington Post, March 18, 2009.

30 Harlan.

Full Name

Marquis Deon Grissom

Born

April 17, 1967 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.