Rickey Henderson

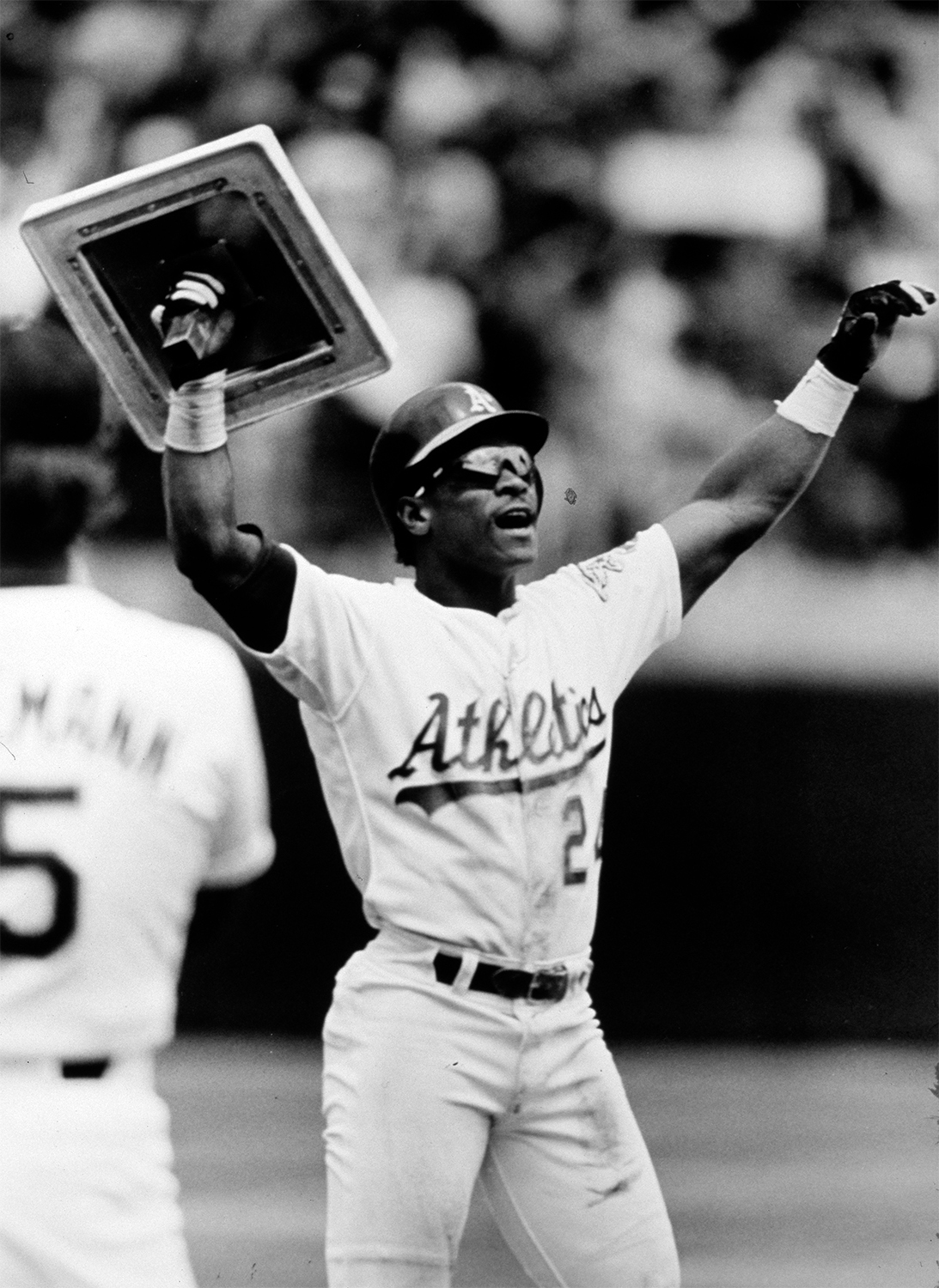

“Lou Brock is the symbol of great base stealing, but today I am the greatest of all time.”1 — Rickey Henderson, May 1, 1991

The above proclamation was part of a short speech made by Oakland’s Rickey Henderson just moments after he stole base number 939 in his career. The thievery of third base in the bottom of the fourth inning in a game against the New York Yankees on May 1, 1991, moved Henderson to number one all-time on the stolen base leader board. To some, his statement may have seemed boastful, disrespectful, or just plain out of line. But the truth stands alone, and the truth is that Rickey Henderson is the greatest base stealer of all time.

The above proclamation was part of a short speech made by Oakland’s Rickey Henderson just moments after he stole base number 939 in his career. The thievery of third base in the bottom of the fourth inning in a game against the New York Yankees on May 1, 1991, moved Henderson to number one all-time on the stolen base leader board. To some, his statement may have seemed boastful, disrespectful, or just plain out of line. But the truth stands alone, and the truth is that Rickey Henderson is the greatest base stealer of all time.

Henderson had been caught stealing by New York catcher Matt Nokes in the first inning of the May showdown. Henderson took note of Nokes’ exuberance at his success. Soon-to-be-second-place Lou Brock had been traveling with the A’s so he could be present when Henderson set the new record. Henderson was in his hometown of Oakland, with his mother in attendance. If he needed extra incentive to run into the record books, Nokes may have provided it.

In his second at-bat, Henderson reached first base when Yankee shortstop Alvaro Espinoza could not field Henderson’s groundball cleanly. Henderson checked into second base when Dave Henderson followed with a single. Jose Canseco followed with a fly out to center field. Henderson then took off, making history with the record-breaking stolen base. A short celebration was held on the field to commemorate the achievement. The 36,139 who were in attendance roared their approval. “I said to myself: ‘It’s all over. You’re No. 1.’” said Henderson. “A lot of pressure left me at that moment, like I was 50 pounds lighter. There had been so much pressure to get it done.”2 Brock told Henderson, “Today you are the greatest competitor that ever ran the bases in the big leagues.”3

Rickey Henderson was born Rickey Nelson Henley on December 25, 1958, in Chicago. He was the second son (after older brother Tyrone), born to John and Bobbie Henley. John Henley left the family two years after Rickey was born. Bobbie gathered up her family (in addition to Tyrone and Rickey, there were brothers Alton, John, and Douglas) and moved them to her native Arkansas and settling on her mother’s farm in Pine Bluff.

After a few years, Bobbie sought a better opportunity for her family in California. She went ahead to search for a place to live and a job that could support her family sufficiently. Once she was settled, she sent for her family to live with her in Oakland. Bobbie met Paul Henderson, whom she married, and he adopted her five sons. The boys took the name Henderson as their surname, and soon two sisters, Paula and Glynnes, joined the family. Paul Henderson was employed by General Motors, while Bobbie worked as a registered nurse.4

Henderson enrolled at Oakland Technical High School, and was a three-sport star in baseball, basketball and football. It was the gridiron that was his first love. “Ronnie Lott, Rickey, and myself were among the top high school players in the country our senior year,” said future A’s teammate Dave Henderson. “We didn’t play against each other, but we saw each other in All-Star workouts and things like that. Ronnie and I saw Rickey take the ball on a sweep one time, hit the corner, and he was gone, 80 yards. I thought I was pretty good, but I remember thinking ‘We gotta tackle guys like that?’”5

“He was such a pleasure,” said his high school baseball coach Bob Cryer. “Always upbeat and positive, always showed up on time and worked hard. I was never very close to Rickey, but I always liked him and wanted the best for him.”6

It was also in high school where Henderson met his future wife, the former Pamela Palmer. They had three daughters: Angela, Adrianna, and Alexis.

Henderson could have gone either route—to college on a football scholarship, or the path to a baseball career in the big leagues. Although his dream was to play professional football, he left the decision to his mother. “It was a tough decision to make, but I didn’t make it,” said Henderson. “My mother made the decision. I loved football; I thought I could be an All-American, but she thought baseball was better for me. I gave her the choice to make and she chose baseball.”7

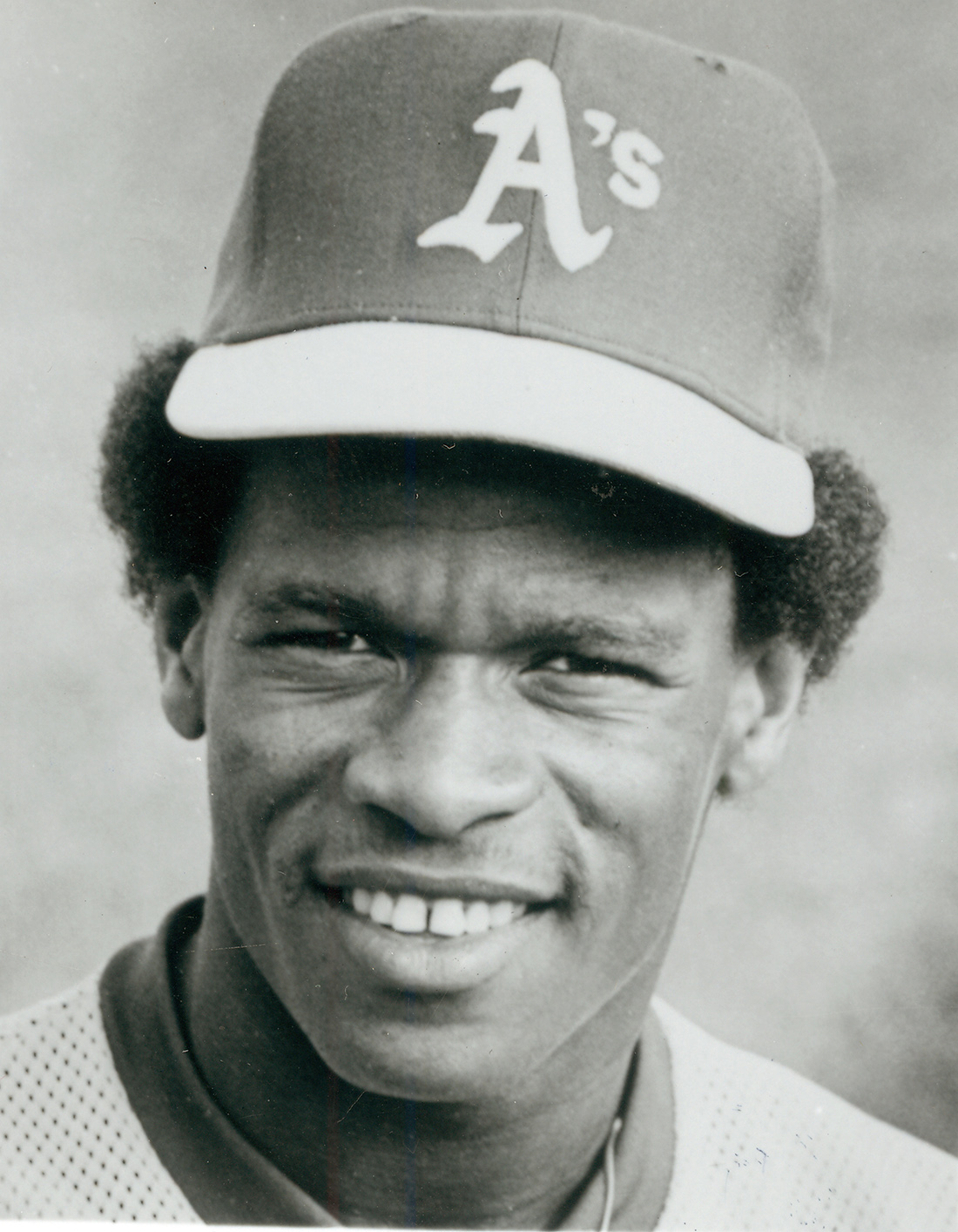

The Oakland Athletics selected Henderson in the fourth round of the free-agent draft on June 8, 1976. Oakland scout Jim Guinn wrote a glowing report of Henderson, thus summarizing his opinion: “Henderson is the best-looking prospect in the Alameda County League and the Oakland Athletic League. I am impressed with this youngster mainly because of his all-around athletic ability.”8

Henderson performed exceptionally well in the minor leagues. He hit above .300 in each class of the minors and was stealing bases constantly once he got to first. Perhaps the one season that gave a glimpse of what the future held was in 1977 at Modesto of the Class A California League. Henderson batted .345, walked 104 times, hit 11 home runs, drove in 69, and scored 120 runs. He also stole 95 bases, giving a lot of the credit for his success to his manager Tom Trebelhorn. “When I got into pro ball, Tom Trebelhorn helped my base-stealing,” said Henderson. “We used to sit up and look at films. I looked at Lou Brock and Ty Cobb, and those were kind of my idols. Trebelhorn was my manager in rookie ball and then he moved up with me to Class A ball. He was probably the biggest influence in my becoming a great base-stealer. He took the time to teach me. He took me out individually and looked at the things I was good at. He took me and made me better. Plus, he also let me steal whenever I thought I could make it, and that gave me a lot of confidence. That was a big thing for me, just coming out of high school, but I guess he saw something in me.”9

He opened the 1979 season at Ogden of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League. After 71 games, Henderson was called up to Oakland and made his major league debut on June 24, 1979. He went 2-for-4 against Texas with a double and a stolen base. Henderson led the team with 33 steals and batted .274.

He opened the 1979 season at Ogden of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League. After 71 games, Henderson was called up to Oakland and made his major league debut on June 24, 1979. He went 2-for-4 against Texas with a double and a stolen base. Henderson led the team with 33 steals and batted .274.

The Athletics were a dismal team that year. Their record was 54-108 and they finished 34 games behind California in the American League West Division in 1979. That all changed when manager Jim Marshall was shown the door and Billy Martin took over. Martin could turn around a club’s fortunes as well as anyone and he did so in Oakland. Remarkably, the Athletics’ record improved to 83-79 as they finished in second place, 14 games behind Kansas City’s juggernaut in 1980.

Martin preached playing aggressively, or “Billy Ball,” as it was commonly referred to. This style suited his team just fine. Henderson also improved, finishing second in the league in walks (117), third in on-base percentage (.420), and he batted .303. He was selected to participate in the first of ten All-Star Games. Henderson was also the recipient of his first and only Gold Glove Award in 1981. Henderson led the league in stolen bases with 100 thefts, beginning his dominance of that category, and his assault on the record books. He accomplished the feat two more times in his career: 1982 (130) and 1983 (108). Henderson led the AL in base thievery the next seven straight seasons and eight-of-nine years. He became the first player, and as of 2017 the only player, in American League history to steal 100 bases in a season.

Henderson had a slightly different theory regarding stealing bases. While most players would study a pitcher’s pickoff move to first base, Henderson paid attention to the pitcher’s move to home plate. He believed that if he could accurately detect when the pitcher was going home with the pitch, he would be able to get more of a jump on his way to stealing a base.

The 1981 season was broken into two halves due to the players’ strike. Henderson led the league in runs (89) and hits (135) as well stolen bases (56). “Rickey is a once-in-a-lifetime player,” said Martin. “You see very few Rickey Hendersons. You might not see another one for fifty years.”10 The pitching staff was sublime. Rick Langford (12-10, 2.99 ERA), Steve McCatty (14-7, 2.33), Mike Norris (12-9, 3.75) and Matt Keough 10-6, 3.40) anchored a formidable staff. The A’s won the West in 1981 and defeated Kansas City in the Division Series. But they were swept by the Yankees in the ALCS. Still, the transformation from just two years prior was remarkable.

But just as fortunes change for the better, the opposite is also true, as the A’s sank to fifth place in 1982. The pitching staff faltered, as not one of the starters posted a winning record. For the first time in his career, Henderson led the league in walks (116), the first time in four seasons that he would do so. He also set a new major league record with 130 stolen bases in 1982, breaking the old mark of 118 set by Brock in 1974. “When I stole 130 bases, we didn’t have the home run hitters, we didn’t have the players,” Henderson later remarked. “When we’d go to spring training all we had were “scrap players” and Billy Martin would say ‘All we can do is run. Everybody’s going to run.’”11

Martin was fired after the season, but resurfaced in New York as manager of the Yankees. The Athletics predictably did not improve under his replacement, Steve Boros, and then Jackie Moore.

For Henderson, he was a showman out on the field. He made snap catches with his glove, pranced around the bases, beat his chest, and was noted as a hot dog. But he felt the fans were paying to see him play, so they should be entertained.

Often he would refer to himself in the third person: “People are always saying, ‘Rickey says Rickey’. But it’s been blown way out of proportion. People might catch me, when they know I’m ticked off, saying ‘Rickey, what the heck are you doing, Rickey?’ They say, ‘Darn Rickey, what are you saying Rickey for? Why don’t you just say I?’ But I never did. I always said ‘Rickey’ and it became something for people to joke about.” 12

Henderson was traded with pitcher Bert Bradley to the Yankees on December 5, 1984. The A’s received five players in return (Stan Javier, Jose Rijo, Eric Plunk, Tim Birtsas and Jay Howell). To complete the deal, Henderson signed a five-year deal worth $8.6 million with the Yankees. Although his stolen base total (66) in 1984 was considerably less than in previous seasons, he still led the league and it was four more than the entire Yankee team. He was also reunited with Billy Martin. “Oakland wanted a power team,” said Henderson. “We had some guys who didn’t want me running. Billy likes the running game. He believes in me. The aggressiveness I have goes with the aggressiveness Billy has.”13 Martin was pleased with the reunion. “Rickey’s the same as (Mickey) Rivers was: Exciting. But he’s got more than Rivers had,” said Martin. “Rivers got thrown out. This guy doesn’t get thrown out.”14

On August 30, 1985, the Yankees trailed Toronto by five games in the AL East. The Yankees won 11 straight from August 31 through September 10. They closed the gap to 1 ½ games. But then the bottom fell out and they posted a 3-10 record from September 11 to September 24. Even though they closed out the season on a run of 10-3, they could not catch the Blue Jays, who claimed the division title by two games. In 1986, they fell short again, finishing in second place to Boston by 5 ½ games.

On August 30, 1985, the Yankees trailed Toronto by five games in the AL East. The Yankees won 11 straight from August 31 through September 10. They closed the gap to 1 ½ games. But then the bottom fell out and they posted a 3-10 record from September 11 to September 24. Even though they closed out the season on a run of 10-3, they could not catch the Blue Jays, who claimed the division title by two games. In 1986, they fell short again, finishing in second place to Boston by 5 ½ games.

For Henderson, the switch from the West Coast to the East did not affect his game. He led the AL in runs in 1985 (146) and 1986 (130). He also added the long ball to his repertoire, slugging 24 home runs in 1985 and 28 in 1986. Henderson was switched to center field from left, where he was stationed defensively in Oakland. Henderson was sidelined with a hamstring injury in 1987, and he missed 67 games. His streak of leading the AL in stolen bases was snapped, although he still managed to swipe 41. Lou Piniella, who had replaced Martin after the 1986 season, questioned Henderson’s commitment to the Yankees. It caused a strain on the manager-player relationship. If there was any doubt, Henderson returned in good health in 1988, and batted .305 and stole 93 bases. “There was a lot of pressure in New York with the George Steinbrenner era — George was very vocal then,” said Dave Righetti. “Rickey was the one guy who seemed to loosen that team up. He relaxed our club, on and off the field, with his personality and the way he played.”15

But New York was mired in the middle of the pack in the AL East. They were not getting much better in 1989, and traded Henderson back to Oakland on June 21, 1989, for pitchers Eric Plunk and Greg Cadaret, as well as outfielder Luis Polonia. “When Rickey got traded to the A’s, we’d walk through the locker room, someone would say ‘Hey Hendu’, and we’d both look up,” said Dave Henderson. “We had to figure something out. So, we’re both in the on-deck circle one day and I say, ‘The first guy who goes deep is Hendu’, the other guy will be Dave or Rickey.’ I forgot the guy had the most leadoff home runs ever. He hits a homer in his next at-bat and he’s coming around the bases laughing like crazy, yelling ‘I’m Hendu! I’m Hendu!’ Well, the pitcher and catcher start getting pissed — they think he’s showing them up. I had to explain things before they started throwing at me. Rickey goes back to the dugout and he’s still yelling, ‘I’m Hendu! I’m Hendu!’ The funny part is, everyone knows he’s always been Rickey and I’ve always been Hendu. But it was still a bad bet.”16

The A’s were the defending American League champs, but lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series in 1988. As Henderson said when he was dealt to New York, the Athletics were looking to build a team of power hitters. And they did just that. In 1988, Jose Canseco led the AL in round-trippers with 42. Mark McGwire added 32 and Dave Henderson smacked 24. Canseco and McGwire, known as the “Bash Brothers”, formed a formidable pair in the middle of the A’s lineup, along with Dave Henderson and Carney Lansford. Now they added Rickey Henderson to the top of the lineup and they were unstoppable.

Oakland outlasted the Royals by seven games to win the AL West. They wiped out Toronto in five games in the ALCS. Henderson was named MVP of the ALCS as he batted .400 (6-for-15), two home runs, five RBIs, eight runs, seven walks, and eight steals. It was a performance for the ages. “We’re a very relaxed club that knows what we have to do to win,” said Henderson. “I like to think that I’m a money player. When we need a steal or drive home a run, I like to think I’ll deliver.”17

The 1989 World Series became known as the “Earthquake Series.” Oakland was facing its northern California neighbor, the San Francisco Giants, when an earthquake measuring 6.9 shook the Bay Area. Candlestick Park lost power, as well as sustaining structural damage. Commissioner Fay Vincent called a halt to the series until further noticed. Play was resumed on October 27 at Candlestick Park. Oakland, which held a 2-0 advantage, went on to sweep the Giants. Henderson did not suffer a hangover from his performance in the LCS. He batted .474 (9-for-19) with one home run and three RBIs, with two triples and three stolen bases. “Rickey was on base in the 1989 World Series and Terry Kennedy was catching for the Giants,” said Lansford. “I walked up to the plate and Kennedy was talking to himself—he was saying. ‘Go ahead and steal it. You’re going to take it anyway.’ Next pitch, he stole. Terry tried to be quick and dropped the ball. That’s how frustrated catchers were behind the plate—they knew he was going to run, but they couldn’t do anything about it.”18

Oakland had little trouble holding off Chicago to win its third straight AL pennant under Tony La Russa in 1990. They outdistanced the White Sox by nine games with a 103-59 record. Henderson was named American League MVP, as he batted .325, and led the league in runs (119), stolen bases (65) and on-base percentage (.439). He tied a career-high in home runs with 28. He finished 31 points ahead of runner-up Detroit’s Cecil Fielder, who led the AL in home runs (51) and RBI (132). “I felt like I was cheated the last three times I was involved in the voting,” said Henderson. “But it’s not my decision. You can’t take away what Cecil did, and if he had won, I would have tipped my hat to him and not felt cheated this time. I still think that (1985) was my best year, but this isn’t far off. The only difference is that I hit for a higher average this season. That was a better year — and I had some great years in New York — but this was good because it helped the team win.”19

Oakland swept the Red Sox in the ALCS. They were heavy favorites to beat Cincinnati in the World Series, but it was the Reds who pulled a major upset, sweeping the A’s. “Some people had some great years on this club,” said Dennis Eckersley. “We won our division and we won a pennant. But we’ll be remembered now for getting our ass kicked. We did everything but win the World Series — and we didn’t look good doing it. I said before that if we didn’t win the World Series, it meant we choked. Well, that’s what we did.”20

Henderson made two trips to the disabled list in 1992, as did Bob Welch, Scott Brosius, and Dave Henderson. In spite of the injuries, the A’s won the AL West by six games over the Twins. However, they were dumped in six games by Toronto in the ALCS.

On July 5, 1993, Oakland hosted Cleveland in a doubleheader. Henderson led off both games with a home run. It was believed that Henderson was the first player in 80 years to accomplish the feat. Harry Hooper of Boston turned the trick on May 30, 1913, against Washington.

Henderson was dealt to Toronto on July 31, 1993, for pitcher Steve Karsay and a player-to-named-later who turned out to be outfielder Jose Herrera. It was a tale of two teams, as the A’s were rebuilding and were in the cellar in the AL West. Toronto was tied with New York atop the AL East at the time of the deal.

Henderson stole 22 bases in 44 games for the Blue Jays. Toronto finished on top in the East and eliminated Chicago in six games of the ALCS. In the World Series, the Jays made it two World Championships in a row as they toppled Philadelphia in six games in the World Series.

Henderson stole 22 bases in 44 games for the Blue Jays. Toronto finished on top in the East and eliminated Chicago in six games of the ALCS. In the World Series, the Jays made it two World Championships in a row as they toppled Philadelphia in six games in the World Series.

Henderson returned to Oakland in 1994 for his third tour of duty with the A’s. He signed a two-year $8.6 million-dollar contact. In spite of some differences that he had with La Russa, Henderson returned to the familiar surroundings of his home. The season was cut short by the players’ strike on August 12, 1994, forcing the cancellation of the remainder of the season and for the first time since 1904, the postseason. Each league was now split into three separate divisions. Oakland finished a scant one game behind Texas in 1994.

The strike extended into the 1995 season, wiping out the first three weeks. Henderson batted .300 and swiped 32 bases in 112 games. But the Athletics finished in last place with a 67-77 record, 11 ½ games behind division-winner Seattle.

Henderson signed a two-year $6.2 million-dollar contract with San Diego in 1996, entering the National League for the first time in his career. “The negative stuff people were talking about when we got him here, that he was going to come to spring training late, that he was going to be a disruptive force in the clubhouse, I haven’t seen it,” said Tony Gwynn. “I’ve seen a guy who’s prepared. I’ve seen a guy who works hard, loves to help young guys, and who has done whatever the club has asked him to do, not only on the field, but off the field.”21

He may have been a great teammate, but his production slipped. Henderson batted .241 and the following year, he was traded to the Anaheim Angels on August 13, 1997. For the 1998 season, Henderson signed a one-year deal with Oakland, the fourth time he suited up for the Athletics. At 39 years of age, Henderson led the AL in stolen bases (66) and walks (118) in 1998 despite a .236 average in 542 at-bats.

The New York Mets inked Henderson to a two-year deal worth $3.9 million after he 1998 season wrapped. He was named The Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year in 1999. He batted .315 with 37 stolen bases, 12 home runs, 42 RBIs, and a .423 on-base percentage. The next year, he was released by the Mets on May 13, 2000. Tempers were hot from the year before when it was reported that during the Mets’ Game Six loss to Atlanta in the LCS, he was playing cards in the clubhouse with Bobby Bonilla. Henderson denied the allegation and demanded that the accuser confront him face-to-face. Of course, it never came to that. He reported late to spring training the following season. “It’s addition by subtraction,” said Mets general manager Steve Phillips.22 Henderson signed with Seattle and finished out the year with the Mariners.

Rickey returned to the Padres in 2001, which proved to be a record-setting one for Henderson. On April 25, 2001, the Padres were trailing Philadelphia, 5-3, heading into the bottom of the ninth inning. Henderson led off with a walk against Phillies closer Jose Mesa. The free pass was the 2,063rd of Henderson’s career, surpassing Babe Ruth for the top spot on the all-time walk list. On October 4, 2001, Henderson hit a home run off Dodger pitcher Luke Prokopec in the third inning. As he neared home plate, Henderson slid into home plate to commemorate the 2,246th run scored in his career, passing Ty Cobb on the all-time runs scored list. “When I first started in the big leagues,” said Henderson, “I felt that as the leadoff hitter, my job was to get on the base paths, create stuff, and score some runs to help my teammates win some ballgames. It just happens over the 23 years I think I went out there and did my job as well as I could do … and all of a sudden, it’s a record breaker … it’s just an honor.

“Going out and scoring so many runs is just not an individual record. It’s a record that you’ve got to have your teammates help you out and in the 23 years I have had some great teammates.”23

On October 7, 2001, the San Diego Padres were hosting the Colorado Rockies in Tony Gwynn’s last major league game. Henderson added to the festivities when he hit a double to right field off pitcher John Thomson to record his 3,000th career base hit. “I thought it was going to come,” said Thomson. “I gave up three hits to him in Colorado. I’m glad he got it. I’d feel really weird if he had three or four at-bats and he didn’t get a hit. Now when someone asks who gave up Rickey Henderson’s 3,000 hit, the answer will be ‘John Thomson’”.24

Boston signed Henderson to a minor league contract in 2002. To this point in his career, Henderson had stolen 1,395 bases, totaling more than the Red Sox franchise, which in the same amount of time, had amassed 1,382 stolen bases.25 The Red Sox passed Henderson early that year.

In a surprise development at the start of the 2003 campaign, Henderson signed a contract with the independent Newark Bears of the Atlantic League. He was 44 years old, making $3,000 playing for a team that was considered on par with a Class AA team in the minor leagues. “If I don’t feel I have the skills, I’d be happy to hang up my shoes and go be with my kids,” said Henderson. “But I know I have the skill. The speed guys who can score runs? I think I am better than the guys in the major leagues. Will I get the chance?”26

Indeed, that opportunity came his way, as Rickey signed on with the Los Angeles Dodgers on July 14, 2003. He played 30 games, batting .208.

That was the last season in the major leagues for Henderson. He ranks first all-time in stolen bases (1,406), runs (2,295), and leadoff home runs (81). Henderson ranks second all-time in walks (2,190). For his career, he smacked 297 home runs, drove in 1,115 RBIs, and batted .279.

In retirement, Rickey was a special instructor for the Mets in spring training, and served as their first base coach in 2007.

Rickey Henderson was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2009. On August 1 that year, Henderson’s number 24 was retired by the Athletics.

In later years, he served as the special assistant to Oakland A’s President David Kaval. The A’s named the playing field at the Oakland Coliseum in Henderson’s honor on April 3, 2017.27

Henderson participated in several public ceremonies to acknowledge the Athletics’ final season in Oakland in 2024, just months before his death at the age of 65 on December 20, 2024.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Photo credits: SABR-Rucker Archive, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 “Quote of the Day,” New York Times, May 2, 1991: A2

2 Michael Martinez, “Safe! Henderson Steals No. 939, and Brock Is Out,” New York Times, May 2, 1992: B17

3 Martinez: B19

4 Rickey Henderson and John Shea, Off Base: Confessions of a Thief, Harper Collins, New York, NY, 1992, 24

5 Ron Kroichick, “The Rickey Show,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 19, 2009: Players File from Hall of Fame

6 David Waldstein, “From Bushrod to Cooperstown,” New York Post, August 15, 1999: 105

7 Glenn Dickey, “Inside Interview: Rickey Henderson,” Inside Sports, June, 1991: 24

8 Jim Guinn, Oakland Athletics Free Agent Report, April 19, 1976, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Player File

9 Glenn Dickey, “Inside Interview: Rickey Henderson”: 24-26

10 Jeff Katz, Split Season 1981, Thomas Dunne Books, St. Martin’s Press. New York, NY, 2015, 250

11 Dickey, “Inside Interview: Rickey Henderson”: 26

12 Dennis Manoloff, “Catching Up With Rickey Henderson,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 29, 2002: D6

13 Dave Anderson, “Henderson: Break Dancer at the Ballet,” New York Times, December 9, 1984: S6

14 Ibid.

15 Kroichick, “The Rickey Show.”

16 Kroichick, “The Rickey Show.”

17 Malcolm Moran, “Dazzling, Daring A’s Win Crown,” New York Times, October 9, 1989: C6.

18 Kroichick, “The Rickey Show.”

19 Michael Martinez, “Henderson Selected Most Valuable Player,” New York Times, November 21, 1990: B13.

20 Tom Barnidge, “A’s Frantically Dial Canseco Hotline During Series But Jose Doesn’t Answer,” The Sporting News, October 29, 1990: 5.

21 Tom Weir, “Inside Rickey’s World,” USA Today, September 25, 2001: 2C.

22 Liz Robbins, “With Patience Long Gone, Mets Release Henderson,” New York Times, May 14, 2000, SP5.

23 Paul Gutierrez, “Record Run for Rickey,” Los Angeles Times, October 5, 2001: B10.

24 Bernie Wilson, “Rickey Register’s 3,000,” usatoday.com & baseballweekly.com, October 8, 2001, accessed November 6, 2017.

25 Retrosheet.org.

26 Tom Verducci, ”What is Rickey Henderson Doing in Newark?”, Sports Illustrated, June 23, 2003: 80.

27 Jon Becker, “A’s to unveil statue of Rickey Henderson at Coliseum next season,” San Jose Mercury-News, September 15, 2017, accessed at http://www.mercurynews.com/2017/09/15/report-as-to-have-statue-of-rickey-henderson-at-coliseum on November 7, 2017.

Full Name

Rickey Nelson Henley Henderson

Born

December 25, 1958 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

December 20, 2024 at Oakland, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.