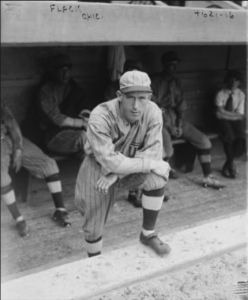

Max Flack

For much of his post-baseball life, Max Flack’s 12-year major-league career was remembered for one thing: his playing for two major-league teams in the same day.

For much of his post-baseball life, Max Flack’s 12-year major-league career was remembered for one thing: his playing for two major-league teams in the same day.

In 2011, 35 years after his death, his major-league career faced a renewed interest in his performance in the 1918 World Series.

Flack was born Conrad John Flach on February 5, 1890 in Belleville, Illinois, to Henry and Mary (Schmidt) Flach. (Belleville is across the Mississippi River from St. Louis.) He was the third of the couple’s four sons. Henry Flach was the custodian at the St. Clair County courthouse for 20 years.

Early in his 16-year professional baseball career, Flack’s name was spelled both Flach and Flack in newspaper accounts. Flack never corrected them and eventually Flack became the common usage.

The 5-foot-7, 150-pound Flack first gained attention for the Belleville Maroons of the semipro Illinois-Missouri Trolley League. He began his professional career in 1911, at the age of 21, when he signed with Tulsa of the Class-D Western Association. His first professional season was tumultuous.

The eight-team league opened its season in the first week of May. Two teams — Joplin and Springfield — disbanded on May 10. Two more teams — Coffeyville and Independence — folded on June 14. After Fort Smith and Tulsa withdrew on June 19, the league ceased operations.

Box scores for the league’s games were published sporadically in local newspapers and statistics and averages for the league are nonexistent. Box scores for 10 of Tulsa’s games showed Flack going 18-for-44. In one three-game stretch against Independence, he was 9-for-14 with three doubles and a triple.

Flack’s play was a highlight for Tulsa, which had a 20-25 record when it folded.

“Flack and Peters are regarded by fans as the stars of the Tulsa aggregate. Both are very fast,” a Coffeyville newspaper commented in May.1

Another reporter noted, “(Tulsa owner Tom) Hayden has one of the best fielders in the entire Western Association in the center garden. That fellow is Max Flack.”2

After the Tulsa season abruptly ended, Flack returned to Belleville. A month later, Hayden, who also owned the Burlington team in the Class-D Central Association, signed him to fill a roster spot after a Burlington outfielder suffered a serious knee injury.

Flack reported to Burlington and made his debut on July 10, going 1-for-3 and driving in the eventual winning run in Burlington’s 6-5 victory over visiting Kewanee. After the game Flack left the team.

“Max Flack of St. Louis disappeared from view sometime after the game on Monday in which he made his debut to Burlington fans,” a newspaper reported. “Flack played in Monday’s game with Kewanee and made an excellent impression on the fans. His sacrifice fly in the ninth inning bringing in the winning run. Why and when he left the city is unknown. It is presumed he returned to his home in St. Louis.”3

Flack resurfaced a month later. A newspaper wrote, “President Tom Hayden of the Burlington baseball club, in a communication to the Burlington Hawk-Eye which was published this morning, charges that President M.E. Justice of the Central Association erred in throwing out the game with Kewanee on July 10, on account of Max Flack in the Burlington line-up. Hayden says that Burlington was never notified of the protest nor was given an opportunity of submitting evidence to show that they were not over the player limit. Hayden says that he suspended Ross and on the same day signed Flack, thus retaining his number of players at 14.”4

On August 21, Flack rejoined the team after Hayden had sold two players to St. Joseph of the Western League. He finished the season with Burlington, which finished second with an 81-44 record, and hit .339 in 15 games.

In early January 1912, Burlington sold Flack’s contract to Peoria of the Three-I League. Flack spent the next two seasons with Peoria. In 1912, he batted .278 in 133 games as Peoria finished last in the eight-team league with a 56-80 record.

In his second season with Peoria, Flack blossomed into one of the league’s best players. He batted .352 with 26 doubles, 13 triples, and a league-high 42 stolen bases. Peoria again finished in last place, with a 56-84 record. Flack’s .352 average just missed winning the league batting title. Decatur’s Pat Flanagan edged Flack .3523 to .3520. Flack was named to the Three-I League all-star team.

“Flack is the best left gardener in the league, and his hitting and fielding has been a great help to the Distillers, in what games they have won,” wrote the Decatur Daily Herald in September.5

But there was more controversy for Flack. With two weeks left in the season, Peoria sold his to Indianapolis of the American Association. A sportswriter speculated that the sale was an effort to reap some revenue before a major-league team could grab Flack in the draft.6

Flack refused to report to Indianapolis. “While reported sold to the Indianapolis club, Max Flack says that he has yet to receive instructions as to when and where to report to the Indians,” a newspaper said. “He is therefore resting in Peoria awaiting further instructions. Flack and (Peoria president) Meidroth had several warm words together Thursday morning. Meidroth accusing the Distiller outfielder of being a ‘loafer’ and a ‘quitter.’ Flack did not like the accusations hurled at him a bit, and it is aid that blows were narrowly averted. It was after this rumpus that Meidroth cut $250 off the price originally demanded of Indianapolis for the player, and the deal it is said, was closed. Selling Flack for $1,250 is giving ball players away.”7

The deal was canceled. According to the Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, “Word was received here yesterday by President Meidroth that Max Flack would be unable to play again this season and that because of his poor condition Indianapolis had recalled all negotiations for his purchase at $1,250. According to a letter received from the offices of the Indianapolis club, Flack’s physician had ordered him to stay out of the game for the remainder of the season and the little gardener refused to report to Indianapolis. Indianapolis intimated they would like first chance to purchase Flack next spring should he return to the game in anything like the form he displayed during the 1913 playing season.”8

In late September, there was more news when it was announced that Flack had been drafted off the Peoria roster by the Detroit Tigers. The next day it was announced that Milwaukee of the American Association, had selected Flack in the Double-A draft.

“There is a controversy on regarding Max Flack, the Peoria outfielder, who was bought by Kelley a few days after the big league drafting season opened,” said the Indianapolis News. Owner (Frank) Navin, of the Detroit Tigers, drafted Flack, but he afterward agreed to cancel the draft and allow Flack to come to Indianapolis. Now Milwaukee comes forward with a claim for Flack under the drafting system, and it was allowed. Kelley will make it a fight to hold him.”9

That wasn’t the end of the of the discussion about where Flack would play in 1914. In February it was reported that he had signed a contract with Chicago of the Federal League. That drew a response from the Milwaukee franchise: “It is made known by the Milwaukee club officials that Max Flack the recruit secured from Peoria and reported as signed with the Federals agreed to terms with Milwaukee on January 15, a fact that presumably makes him ineligible to play with the Gilmore crowd.”10

In the end, Flack joined Chicago. Early reports from Chicago’s spring-training camp in Shreveport, Louisiana, praised Flack.

“Little Flack, a Three-I League recruit, has shown splendidly in fielding and is sure of being carried,” reported the Inter Ocean of Chicago.11

The Tribune said, “Indications also point to a battle for an outfield job here, because little Max Flack, the Three Eye league recruit, is doing too much to be a bench warmer. He showed Manager (Joe) Tinker something fancy today in a hook slide for second — so fancy that Tinker failed to tag him, though he had the ball in plenty of time.”12

When the Chi-Feds opened their season on April 16 at Kansas City, Flack was their starting left fielder and leadoff hitter.

In the final two weeks of the regular season, the Chi-Feds won seven of nine and on October 3 were in first place with a two-game lead over Indianapolis. Over the final five days of the regular season, the Chi-Feds went 2-3 while the Hoosiers won their final six games to pass Chicago. The Hoosiers finished 88-65-4, while the Chi-Feds were 87-67-3.

For the season, Flack hit .247 in 134 games with a team-high 37 stolen bases.

Before the 1915 season the club, which had officially become the Whales, signed two outfielders — Les Mann, who had played in the 1914 World Series with the Boston Braves, and Charlie Hanford, who had played for the Buffalo Federal League team in 1914. In mid-March, newspaper reports said that Whales manager Joe Tinker was considering a platoon system in 1915. The Tribune said, “The addition of Leslie Mann and Charlie Hanford, outfielders, has supplied the north siders with reserve strength to spare. With Mann and Hanford, both strong right-handed hitters, Tinker expects to use two sets of outfielders.”13

But Flack was in the lineup nearly every day in 1915. He batted .314 and led the team with 37 stolen bases, ranking fourth in the Federal League in both categories. He played in 141 games. Of the 138 games in which he appeared in the field, he spent time in left field in 61 games and time in right field in 81 games.

The Whales (86-66) and St. Louis Terriers (87-67) finished in a tie for first place, but the Whales’ winning percentage was .000854 better than the Terriers and they were named champions.

In December 1915 the Federal League, American League and National League reached a deal and the Federal League ceased operation. Whales owner Charles Weeghman bought a majority interest in the Chicago Cubs and he merged the Whales and Cubs franchises.

After appearing in four World Series in a five-year span between 1906 and 1910 and winning at least 88 games in 1911, 1912 and 1913, the Cubs were rebuilding in 1916. They were 78-76 in 1914 and fell to 73-80 in 1915.

In early March of 1916 as the Cubs prepared to open training camp, it was reported that Flack was the only regular not signed to a 1916 contract and that he was holding out. But Flack signed and was with the team at the start of spring training in Tampa, Florida. Late in training camp, Flack, expected to be the Cubs’ starting right fielder, was sidelined with a “bad cold, the only training setback the club has received. Flack can stand a layoff as well as any man on the team. His batting is good and he had already acquired his usual speed.”14

Flack was in the Cubs’ opening day lineup on April 12 (in Cincinnati) and would be a mainstay in the Cubs lineup for the next six seasons. The Cubs started the 1916 season strong, putting together a seven-game winning streak in late April. They were 15-13 on May 18 and still at .500 (36-36) on July 7. But the Cubs went 23-37 after August 1, to finish in fifth place with a 67-86 record. Flack batted .258 and had a team-high 24 stolen bases in 141 games. He led the NL with 39 sacrifices.

In 1917 he batted .248 in 131 games as the Cubs finished fifth with a 74-80 record.

In early 1918, after going 2-3 in their first five games, the Cubs won nine consecutive games to improve to 11-3. They didn’t let up. By early July, the Cubs were 50-20. They eventually won their first pennant since 1910 with an 84-45 record, finishing 10½ games ahead of the New York Giants.

Flack, who batted .257 in 123 games during the regular season, was 5-for-19 with four walks in the World Series against the Boston Red Sox, who won the Series in six games.

Game One provided a light-hearted moment. The Red Sox went into the Series concerned about Whales outfielder Leslie Mann, who hit .288 in 1918 and was known to crowd the plate when hitting. Boston’s pitchers were told to pitch him inside.

With Boston clinging to a 1-0 lead in the bottom of the fifth inning, Red Sox pitcher Babe Ruth remembered the strategy. With Flack at the plate and two outs, Ruth, thinking he was facing Mann, threw inside. Flack was nicked by the pitch and awarded first base. Ruth got the third out of the inning and returned to the dugout, expecting to be complimented. But none of his teammates mentioned it.

“‘Say, fellows,’ he finally blurted out in pride. ‘I guess I didn’t dust off that Leslie Mann that time! That stopped him!’”15

“For two days, the Chicago players were puzzled at the loud burst of laughter that came from the Red Sox dugout. Ruth had mistaken Max Flack for Leslie Mann and had dusted off the wrong man!”16

“That’s a mighty good joke on Babe Ruth,” said Flack when he heard about it, “but where do I come in. I took the sock on the neck.”17

The Red Sox won two of the three games in Chicago before the series switched to Boston for the final three games. In Game Four, Flack, who was 3-for-10 in the first three games, was 1-for-4 but was picked off twice — the only player in World Series history to be picked off twice in one game. After opening the game with a single, he was picked off first by Red Sox catcher Sam Agnew. In the third inning, he reached after hitting into a fielder’s choice. He advanced to second, where he was picked off by Ruth. The Red Sox won the game, 3-2.

In Game Five, won by the Cubs 3-0, Flack was 0-for-2 with two walks. In Boston’s Series-clinching 2-1 victory in Game Six, he was 1-for-3 with a stolen base.

Until 2009, getting hit by a Ruth pitch in Game One was what was most remembered about Flack’s 1918 World Series.

In The Original Curse: Did the Cubs Throw the 1918 World Series to Babe Ruth’s Red Sox and Incite the Black Sox Scandal? Sean Deveney wrote, “(Flack) was brought up as possibly being involved in throwing the 1918 World Series between the Cubs and the Red Sox. He made crucial errors and misplays throughout the series.”18

The subject drew renewed interest in early 2011, when the Chicago History Museum released testimony from the 1920 grand jury that had looked into corruption during the 1919 World Series between the Chicago White Sox and the Cincinnati Reds. In his testimony to the grand jury, Eddie Cicotte, who admitted being paid to throw the Series to the Reds, testified that his Black Sox got the idea from the 1918 Cubs. Cicotte’s testimony “was frustratingly vague as he avoided providing any names or details or even whether he thought that the Cubs had indeed thrown the series. Cicotte charged that baseball didn’t want to investigate, happy to concentrate on the Black Sox scandal instead.”19

Deveney’s book questioned a series of gaffes by Flack in Game Four. In addition to his two baserunning miscues, a defensive lapse (playing too shallow with Ruth at the plate), and hitting into a routine groundout in the Cubs’ two-run eighth inning were also called into question. In Game Six, Flack, who led the NL in fielding percentage twice in his career, “dropped a routine two-out drive to right field in the third, allowing Boston to score its only two runs in a 2-1 victory.”20

“There isn’t anything inherently suspicious to me,” said Bill Lamb, a longtime member of the Society for American Baseball Research who serves on the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee. (He also was a New Jersey prosecutor for 33 years.) “I am aware people do bad things, but just because something is conceivable doesn’t make it so. Where’s the proof?”21

Flack recovered to hit .294 in 116 games for the Cubs in 1919. He had 6 home runs and 35 RBIs and walked 34 times. In 1920, he batted .302 with 4 home runs and 49 RBIs in 135 games, with a career-best .373 OBP.

The Cubs slipped to seventh place in 1921, going 64-89, but Flack enjoyed a solid season, hitting .301 with 6 home runs and 37 RBIs. He struck out just 15 times in a career-high 572 at-bats.

The Cubs started the 1922 season by winning 10 of their first 13 games. But they fell to 18-20 after a loss to the St. Louis Cardinals on May 29. The next day, Flack was traded.

In a holiday doubleheader in Chicago, the Cubs won the first game, 4-1, as Flack, playing right field, went 0-for-4 with an RBI. After the game, Flack was traded to the Cardinals for outfielder Cliff Heathcote, who had gone 0-for-3 for the Cardinals in the first game.

The players switched clubhouses, and in the second game, won by the Cubs, 3-1, Heathcote went 2-for-4 for the Cubs while Flack went 1-for-4 as the Cardinals’ leadoff hitter. Flack and Heathcote became the first two players in major-league history to play for two teams in the same day.

For the rest of the season, Flack, who hit .222 in 17 games with the Cubs before the trade, hit .292 in 66 games with the Cardinals.

In 1923 he hit .291 in 128 games with the Cardinals. In 1924, he played in a career-low 67 games, batting .263.

Flack’s final big-league season was 1925. He took a pay cut to remain with the Cardinals.

“When I went in to talk salary with (Cardinals general manager Branch) Rickey in 1925, Rickey told me I ought to go to the Pacific Coast League where I could play every day. I balked, because I didn’t want to go to the minors and my family lived in the St. Louis area. Anyway, after a lot of talking, I said to Rickey I’d take a cut if he’d let me stay. ‘That will be fine,’ said Rickey. He cut me $1,500.”22

Flack hit .249 in 79 games with the Cardinals in 1925. He spent the 1926 season with Syracuse of the International League, hitting .243 in 121 games.

For his 12-season big-league career, Flack batted .278 in 1,411 games. After retiring from baseball, he was the chief custodian at East St. Louis (Illinois) High School. He died on July 31, 1975, in Belleville at the age of 85. He was survived by his son, Raymond, and daughter, Maxine. His wife, Stella, had died in 1974.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Findagrave.com, Newspapers.com, and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Realm of Sport,” Coffeyville (Kansas) Evening Star, May 10, 1911: 5.

2 “About the Tulsa Team,” Coffeyville Daily Journal, May 16, 1911: 3.

3 “Max Flax Has Skipped Town,” Daily Gate City (Keokuk, Iowa), July 12, 1911: 1. The quotation is as it appeared in the original publication.

4 “Hayden Starts a Controversy,” Daily Gate City, August 11, 1911: 3.

5 “All-Star III Players Named in Herald’s Selections for 1913,” Daily Herald (Decatur, Illinois), September 7, 1913: 7.

6 “Max Flack Sold to Indianapolis,” Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, August 29, 1913: 15.

7 “Max Flack Is Peeved,” Davenport Daily Times, September 4, 1913: 11.

8 “Flack Deal Off; Player Is Hurt,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, September 15, 1913: 3.

9 “May Lose Flack,” Indianapolis News, September 24, 1913: 10.

10 “Sport Stories Briefly Told,” Decatur (Illinois) Daily Review, February 18, 1914: 5.

11 Roland Coffey, “Chifeds Are Ready for Pennant Race,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), March 29, 1914: 23.

12 Sam Weller, “Blokes to Play ‘Feds’ for Title,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1914: 11.

13 James Crusinberry, “Whales to Face Stovall’s Gang,” Chicago Tribune, March 14, 1915: Part 3, 1.

14 “Boxing — Sports of All Sorts — Baseball,” The Day Book (Chicago), April 5, 1916: 11.

15 Bozeman Bulger, “Ruth Was Twirler in Series of 1918,” Lincoln Journal Star, January 19, 1926: 10.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Roger Schlueter, “Answer Man: Did a Belleville Man Help the Cubs Throw the 1918 World Series?” Belleville News Democrat, March 6, 2015. bnd.com. Sean Deveney’s The Original Curse: Did the Cubs Throw the 1918 World Series to Babe Ruth’s Red Sox and Incite the Black Sox Scandal? was published by McGraw-Hill Education in 2009. The quotations are from Schlueter’s article and not Deveney’s book.

19 Schlueter.

20 Schlueter.

21 Schlueter.

22 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1975: 46.

Full Name

Max John Flack

Born

February 5, 1890 at Belleville, IL (USA)

Died

July 31, 1975 at Belleville, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.