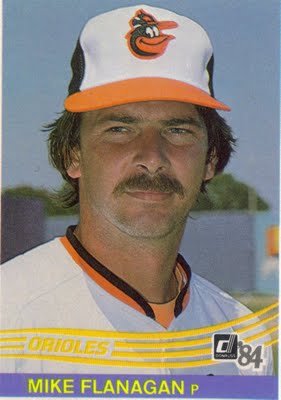

Mike Flanagan

Mike Flanagan was the ace of a Baltimore Orioles staff for over a decade. The 1979 Cy Young Award winner helped the Orioles to two World Series appearances and was part of a combined no-hitter in 1991. He relied on a repertoire of pitches, including a fastball, heavy sinker, slow curve, and changeup.

Mike Flanagan was the ace of a Baltimore Orioles staff for over a decade. The 1979 Cy Young Award winner helped the Orioles to two World Series appearances and was part of a combined no-hitter in 1991. He relied on a repertoire of pitches, including a fastball, heavy sinker, slow curve, and changeup.

Michael Kendall Flanagan was born on December 16, 1951, in Manchester, New Hampshire, into a baseball family. He attended the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and his first major-league game was on September 5, 1975. Mike’s grandfather, Edward F. Flanagan Sr., signed his first professional baseball contract with the Boston Braves in 1913. He was a barnstormer who would pitch the first game right-handed and then pitch the nightcap left-handed. Mike’s father, Ed Jr., signed with the Boston Red Sox in 1947 and pitched for five years in their minor-league system, (in Oneonta and Auburn) and one year in the Detroit system (Lynn and Ottawa). Mike grew up playing catch with both his father and grandfather. His cousin Bill Manning had been a minor-league shortstop and would spend hours every Sunday throwing batting practice to Mike. Ed Jr.’s brother had been a catcher in the Tigers’ farm system.

Mike Flanagan was drafted by the Baltimore Orioles in the seventh round of the 1973 amateur draft. He was accustomed to success. By the time he was drafted, he’d lost perhaps ten games in his entire life. At 11 years old, Mike pitched the South End Little League All-Stars to the state championship game. At 14, he was pitching in the Babe Ruth finals in Fairbanks. He was drafted by Houston in 1971 but opted to go to college. He also pitched in the Cape Cod League before graduating from UMass with a record of 12 – 1. He led the Yankee Conference in wins (9), strikeouts (89), and ERA (1.72) as a sophomore. The Orioles might have drafted him higher than the seventh round, but he had elbow problems in high school. John Stokoe signed him, convinced his arm was sound.

After being drafted by Baltimore, he went 4-1 in ten starts in 1973 (Miami), 12-10 in 1974 (Miami and Asheville), and 13-4 in 1975 (Rochester) before being called up to the big club. Mike had tied for the Southern League in shutouts while with Asheville in 1974, and he led the International League in 1975 with his .765 winning percentage. His minor-league record was 35-16, and Flanagan sported a 2.21 earned run average.

He appeared in two games for the Orioles in 1975. On September 5, 1975, Flanagan appeared as a reliever in a home game against the New York Yankees and did not earn a decision. His first decision came when starting the last game of the season, A September 28 contest on the road against the Yankees. Mike pitched eight scoreless innings, striking out five batters, but he allowed two singles and a walk to start the bottom of the ninth, and he was replaced by reliever Dyar Miller, who allowed all three runners to score, giving Mike his first decision, a 3-2 loss.

Flanagan started the 1976 season with the Orioles, but his record was 0-3 in ten games. Consequently, he was sent down to AAA Rochester on July 2. He pitched very well, amassing a 6-1 record for the Red Wings. He was called back up to the Orioles on August 11 but dropped his next two decisions. Mike picked up his first major-league victory on September 1, 1976, pitching a six-hit complete game to best the Kansas City Royals, 7-1. He struck out five and allowed only singles to the KC batters. Flanagan had retired the final eight batters to secure the win. He finished the 1976 campaign with a 3-5 record.

Mike earned his first career shutout in a 2-0 victory over the Athletics on May 14, 1977. He allowed five hits and two walks and struck out seven before an Oakland crowd of 4,216. On September 27, 1977, Mike Flanagan came within one of the Orioles’ strikeout record when he fanned 13 in a 6-1 win over the Tigers. It was the 12th win in his last 14 decisions. He would finish his first full season with Baltimore with a 15-10 record in 33 starts.

In 1978, Mike started 40 games for the Orioles. By the beginning of July, Flanagan, who wore #46 for the Birds, pitched to a 12 – 5 record and was named to the American League All-Star team. He finished the season at 19-15 for the fourth-place 90-win Birds, completing 17 games (including two shutouts) in 281 1/3 innings. He had a near no-hitter, giving up a ninth-inning, two-out hit (a home run to Cleveland’s Gary Alexander) on September 26. He then gave up two more singles before Don Stanhouse came on to preserve the victory.

Flanagan pitched a seven-hitter to become the first 20-game winner of 1979 in a 5-1 victory, part of a doubleheader sweep over the Toronto Blue Jays on September 3. Pitching coach Ray Miller told reporters, “The thing that’s underrated about Mike is his fastball. We clocked it at 89 mph tonight and only five others have clocked faster this season.”1 Mike credits much of his 1979 success to the development of a change-up, taught to him by fellow Oriole hurler Scott MacGregor.

An interesting phenomenon occurred during the 1979 season, and the press dubbed it the “Mike and Ken Show.”2 It seemed that whenever Mike Flanagan started a game, Ken Singleton would hit a home run. Of Ken’s 35 home runs in the 1979 season, 15 were swatted with Mike on the mound. Even more remarkable, since Mike made his debut in September 1975, 34 of Ken’s home runs came in games in which Mike started (through the end of 1979).

His 23-9 record was established with 190 strikeouts in 265 2/3 innings. He allowed 107 runs, 23 HR, and only 70 walks, completing 17 games. The lefthander was a landslide winner of the Cy Young Award in 1979, the fifth time in 11 years an Orioles hurler had won or shared the award. “Maybe I was the best pitcher, but I was also on the best team,”3 he said. Mike was the only pitcher named on all 28 ballots. He was named Pitcher of the Year by The Sporting News, and the A.P. and U.P.I. selected him as top left-hander to their all-star teams. Although Mike finished sixth in league MVP voting, he was named Graduate of the Year by both the Junior American Legion and Babe Ruth programs for his success in 1979.

Manager Earl Weaver chose Flanagan to be the Game One starter in the World Series against the Pirates. He went the distance in a 5-4 win. His teammates put up five runs in the first inning as a cushion. He started Game Five and took the loss in a 71 Pittsburgh win. Flanagan was one of five relievers to pitch the ninth inning of Game Seven, which the Orioles lost to Pittsburgh.

The town of Manchester declared Saturday, November 10, 1979, as Mike Flanagan Day and honored the Cy Young winner with a motorcade through town. About 1,000 fans turned out for the event to see the 27-year-old lefthander.

In the next season, 1980, Mike was again valuable to the Birds, winning 16 games. This would give him 58 wins in three consecutive seasons and 73 wins from 1977 through 1980.

On August 26, 1980, a short article appeared over the AP wire. The former wife of one of the American hostages in Iran told reporters that her ex-husband, William Keough, had written a letter to Mike Flanagan asking for an autograph. None of the family members had heard from Mr. Keough since he had been taken captive, but they were encouraged that he had written to the Baltimore pitcher. The family speculated that he may have written several letters, but the letter to Flanagan was the only one that got through. Unfortunately, the story does not mention if Flanagan ever sent the autograph to Mr. Keough.

In September 1981, Mike developed tendonitis in his elbow. He had been the iron man of the O’s staff, making 157 consecutive starts since 1977. Mike told reporters that, “It’s just an oil change and a 30,000-inning checkup.”4 In 1987, the tendonitis returned. After making only three pitches in a game against the Angels on May 17, Mike was forced to leave the game. He had also missed four starts in 1986 because of the same problem.

The southpaw signed a five-year contract (with an option for a sixth year) extending through the 1986 season on February 19, 1982. He had submitted to salary arbitration prior to the signing. Interestingly, Mike’s agent, Jerry Kaplan, had submitted a demand of $485,000 and the Orioles had submitted $500,000. This became only the second time in the seven-year history of salary arbitration that a player had submitted a figure lower than his club.

Despite being a Cy Young Award winner, Mike might forever be known as the father of one of America’s first test tube babies. On July 9, 1982, Mike’s wife Kathy (the Flanagans were married in January 1977) gave birth to a healthy daughter, Kerry Ellen Flanagan. Doctors at Greater Baltimore Medical Center said it was the first case in the United States of an in vitro fertilization baby being delivered by normal, non-Caesarean methods. Kerry weighed in at eight pounds, eight ounces.

In preparation for the 1983 World Series, the Orioles pitchers took extra batting practice. Flanagan told reporters, “I think my last home run was in Rochester of the International League. I think a fan and I split $600 between us. They were giving a prize for the player who hit a home run leading off an inning and I came up to lead off the sixth. The people started to boo me because they didn’t think I could hit one. But they gave me a standing ovation as I rounded the bases.”5 During Baltimore’s pennant-winning 1983 season, Flanagan went 12-4 with a 3.30 ERA in 20 starts.

Mike notched his 150th career win on June 26, 1988, a 4-1 victory over the Detroit Tigers. 1988 marked the eighth season in which Flanagan garnered double-digit victories.

The Toronto Blue Jays had acquired Flanagan from the Baltimore Orioles on August 31, 1987, for minor-league pitcher Oswald Peraza, who was 24, and a player to be named. The Blue Jays released their 48-year-old star, Phil Niekro, to make room for Flanagan. Flanagan was part of Blue Jays history long before being traded to Toronto. Mike was the losing pitcher in Toronto’s most lopsided victory ever (a 24-10 shellacking of the Orioles on June 26, 1978). The southpaw also had the best record against the Blue Jays (17-10) of any American League pitcher. Flanagan returned to the Orioles at the beginning of the 1991 season.

On July 13, 1991, Bob Milacki started a game against the Oakland Athletics and pitched six no-hit innings before leaving the game after being struck by a line drive. Flanagan came in and walked one but retired the side without allowing a hit. Mark Williamson pitched a perfect eighth inning and Gregg Olson pitched a perfect ninth, preserving a combined no-hitter against the A’s. This has to be the highlight of Flanagan’s relief pitching career.

Mike played in his final game on September 27, 1992, pitching two scoreless innings, striking out one and allowing two hits. He had pitched in 15 games for Baltimore that season. He finished his career with a record of 167 wins against 143 losses. He had gone 141-116 with the Orioles and 26-27 with the Blue Jays. His career ERA was 3.90 in 2,770 innings pitched over 18 major-league seasons. He had earned his first save in 1977 and earned three more in 1991. Mike was used primarily as a middle reliever for the Orioles in 1991 and 1992, a stretch of 106 games. Of note is the fact that Mike Flanagan was the last Oriole to throw a pitch at Memorial Stadium. He struck out 1,491 batters and pitched 101 complete games in his career.

In 1994, Mike Flanagan was named to the Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame. He served as the O’s pitching coach twice, in 1995 and in 1998. In between, and then again from 1999 to 2002, he worked as a broadcaster for the ballclub, continuing his association with Baltimore baseball.

In early November 2002, Mike interviewed to become the first “permanent” general manager for the Boston Red Sox in the post-Yawkey era. He also was interested in the Orioles’ vice president of baseball operations job, and the Orioles made him that offer. He shared VP of baseball operations post with Jim Beattie. On October 11, 2005, Flanagan was promoted to executive vice president of baseball operations. This made him the first Cy Young Award winner to garner a general manager-level position in baseball.

When the Orioles hired Andy MacPhail in June 2007, Flanagan’s responsibilities in the front office were lessened, after six years as Baltimore’s top executive. When the Baltimore Sun interviewed him prior to the 2007 season, he was asked about the move he was most proud of, to which he responded, “not drafting [Nick] Markakis as a pitcher.”6

In March 2010, Mike Flanagan returned to the Baltimore organization as a color analyst for the Mid-Atlantic Sports Network, after having spent more than 30 years with the Birds as a player, coach, front office executive and broadcaster. In the booth, he would be reunited with former teammates Jim Palmer and Rick Dempsey.

Unfortunately, Flanagan was only in his second year as an analyst when he was found near his home, dead from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound. On August 24, 2011, Michael Kendall Flanagan took his life. Police speculated that he was concerned over finances.7 Others have suggested that he may have been upset with the perception of his responsibility for the Orioles’ prolonged failure as an organization.8 He was 59 years old and was survived by his second wife Alex and daughters Kerry, Kathryn, and Kendall. A year after his death, Alex told a reporter, “Did you ever notice Mike when he came off the mound after a good inning? He always had his head down.”9 He had been suffering from depression, and his wife said, “he used to talk about shadows.”10 Alex continued to report that Flanagan had been seeing a psychiatrist for 20 years, but she was not sure if he or the doctor ever identified the source of Mike’s shadows, stating, “Mike always wanted to be the one who told people the good news. He never wanted to be the bearer of bad news.” His success as a pitcher had evidently not been enough. “Mike was such a unique guy, talented, witty, funny,” said Hall of Famer Jim Palmer. “You are not ready to lose someone like Mike Flanagan. But on the other side, I feel lucky to be part of the organization and have had him as a friend and a confidant and buddy.”11

Sources

The author accessed various dated/undated articles and newspaper clippings in Michael Kendall Flanagan’s file at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, The National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, New York, on March 24, 2010. Special thanks to Gabriel Schechter for his assistance in my data collection.

The author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the 1983 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide.

Notes

1 Taken from unnamed newspaper clipping, dated March 19, 1998, in Flanagan’s Hall of Fame player file.

2 Unnamed player file clipping, dated September 8, 1979,

3 Unnamed player file clipping, dated October 31, 1979,

4 Unnamed player file clipping, dated September 19, 1981,

5 New York Post, October 12, 1983.

6 “Q&A with Mike Flanagan,” Baltimore Sun, March 24, 2007. Found online at http://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/baseball/bal-sp.osqampa24mar24,0,6698726.story?coll=bal-local-harford.

7 “Former Orioles pitcher Flanagan dead in apparent suicide.” Baltimore Sun, August 25, 2011. http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2011-08-25/sports/bs-md-co-flanagan-house-death-20110824_1_office-executive-and-broadcaster-apparent-suicide-mike-flanagan. Accessed September 17, 2013.

8 “Report: Mike Flanagan killed himself over ‘prolonged failure’ of the Baltimore Orioles (updated).” Deadspin.com, August 25, 2011. http://deadspin.com/5834218/mike-flanagan-who-won-a-world-series-and-cy-young-award-with-the-orioles-found-dead-updated. Accessed September 18, 2013.

9 “Death of Mike Flanagan, Orioles great, leaves shadows of doubt.” Baltimore Sun, August 18, 2012. http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2012-08-18/news/bs-md-rodricks-flanagan-20120818_1_mike-flanagan-orioles-president-for-baseball-operations. Accessed September 17, 2013.

10 Ibid.

11 Baltimore Sun, August 25, 2011.

Full Name

Michael Kendall Flanagan

Born

December 16, 1951 at Manchester, NH (USA)

Died

August 24, 2011 at Monkton, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.