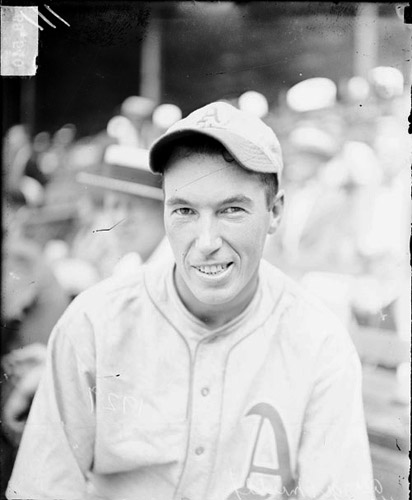

Mule Haas

The October 3, 1929, issue of the Sporting News printed a sampling of observations of beat writers from around the Major Leagues with their predictions on who would win the World Series between the Philadelphia Athletics and the Chicago Cubs. Of the 106 writers polled, 53 picked Philadelphia, 42 liked the Cubs, and 11 others abstained from making a choice. Although both squads could rip the cover off the ball, the scribes pointed to the strength of the A’s battery. Philadelphia boasted one of the best backstops ever in Mickey Cochrane, while the Cubs had Zack Taylor and Mike Gonzalez, who were filling in for the injured Gabby Hartnett. Pat Moran, who led the National League in wins with 22, led a fine Chicago staff that included Guy Bush and Charlie Root. George Earnshaw, a strapping right-hander, led the junior circuit in victories with 24. He was joined by 20-game winner and ERA champ Lefty Grove, 2.81 and Rube Walberg. The cunning Mack stacked the deck against the Cubs’ dominant right-handed bats. He inserted the right-handed Howard Ehmke in the rotation while Grove and Walberg, both lefties, pitched out of the pen.

The October 3, 1929, issue of the Sporting News printed a sampling of observations of beat writers from around the Major Leagues with their predictions on who would win the World Series between the Philadelphia Athletics and the Chicago Cubs. Of the 106 writers polled, 53 picked Philadelphia, 42 liked the Cubs, and 11 others abstained from making a choice. Although both squads could rip the cover off the ball, the scribes pointed to the strength of the A’s battery. Philadelphia boasted one of the best backstops ever in Mickey Cochrane, while the Cubs had Zack Taylor and Mike Gonzalez, who were filling in for the injured Gabby Hartnett. Pat Moran, who led the National League in wins with 22, led a fine Chicago staff that included Guy Bush and Charlie Root. George Earnshaw, a strapping right-hander, led the junior circuit in victories with 24. He was joined by 20-game winner and ERA champ Lefty Grove, 2.81 and Rube Walberg. The cunning Mack stacked the deck against the Cubs’ dominant right-handed bats. He inserted the right-handed Howard Ehmke in the rotation while Grove and Walberg, both lefties, pitched out of the pen.

Those writers who selected the Athletics may have been on to something. Philadelphia won the first two games of the Series, as their pitchers combined for 26 strikeouts. The Sporting News lent some humor, accurate as it was, in their October 17 edition with the headline, “They Were From The Windy City, So They Fanned Up Quite A Breeze”. The Cubs came back to win Game Three, and looked well on their way to evening up the Series as they raced out to an 8-0 lead in Game Four. Root was pitching a three-hitter when the A’s erupted for 10 runs in the seventh inning, won the game, 10-8, and took a commanding lead in the series.

The Cubs led, 8-6, in that eventful seventh when A’s center fielder Mule Haas greeted relief pitcher Art Nehf with a shot to center field that Hack Wilson lost in the bright sun. The result was an inside-the-park home run that narrowed the Cubs advantage to a single run, 8-7. Earlier in the inning, Wilson had lost sight of the ball on a single by Bing Miller, also because of the sun. “I don’t blame Wilson a bit,” said Haas. “Believe me that sun was terrible out there and maybe I got a break that I didn’t lose one myself.”1 Chicago manager Joe McCarthy said, “You can’t beat the sun, can you?”2 Ed Pollock of the Philadelphia Public Ledger wrote that after Haas’s home run; “The A’s dugout was seething with joyous and romping players. The retiring McGillicuddy found himself being jazzed around and embraced by a demonstrative employee. A dozen pair of hands reached into the bat pile, so neatly arranged in front of the dugout and sent the lumber skyrocketing in disorder.”3

Game Five followed the same script, as Malone was throwing a two-hitter at the A’s and nursing a 2-0 lead. Philadelphia manager Connie Mack sent pinch-hitter Walter French to the plate to lead off the bottom of the ninth inning. Malone struck him out, but the fans at Shibe Park came alive when Max Bishop singled down the third base line, and Haas again came through. This time his homer left the park, over the right field fence and just like that, the A’s had knotted the score. Miller later doubled home Al Simmons with the winning run to give the Athletics the World Championship. “I could see myself going back to Chicago before that ninth inning,” said Mack, “and I was wondering whom I would pitch in the next game there. I had my reservations made and my tickets bought.” 4 Chicago shortstop Woody English was having the same thought as Mack. “All we needed was three more outs and we were back in Chicago for the last two games. It looked like we had it salted away.”5

Haas recalled the at-bat. “That hit of Bishop’s in the ninth inning inspired me when I went up to the plate in [the] ninth,” said Mule. ”It was a ‘do-or-die’ inning for the Athletics. I knew that Malone would try to breeze over the first strike. That’s what he gave me, a fast ball and high. It was money from home for your little Georgie. I swung hard, and when I saw that ball going over the right field stand, well, I can tell you just how I did feel. It was a grand and glorious feeling. Then too, I got a great kick out of the crowd yelling in the stands. I’m the happiest kid in the world to-night.”6

George William Haas was born on October 15, 1903, in Montclair, New Jersey. He was the second child (brother Howard) of George and Marguerite Haas. The elder George tried his hand at baseball, pitching for a couple of semi-pro teams. He made his living working as a plumber for the water department. Often young George would serve as his dad’s apprentice in his formative years.

Hass attended Montclair High School. His intent after high school was to attend Columbia University and take business courses. However, one day his shoes were taken from the high school gymnasium dressing room. He could not afford another pair and demanded that the school purchase him a new pair. The principal declined to accommodate Haas, and he abruptly left school. Haas decided to focus his efforts on semi-pro baseball and working with his father, knowing full well that he would lack the necessary credits to attend Columbia.

“I was chasing the outfield for a team in Orange, N.J.,” recounted Haas. “Towards the end of the summer, a couple of big-league scouts made me offers. One of the scouts was Jim Johnstone, a former National League umpire who worked a lot of our games, and the other was Mike Drennan of the A’s.

“Well, I listened to both their offers and made a date to see them again the next day and give my answer. The way it turned out was Johnstone saw me first and I signed with him, for Pittsburgh, without waiting a half hour more to keep my appointment with Drennan. Believe me, not waiting those 30 minutes cost me plenty of punishment in the next few years.”7

The Pirates assigned Haas to Williamsport of the New York-Pennsylvania League in 1923. Haas scuttled through the Pirates’ farm system the next few years. The left-handed swinging Haas showed a propensity for hitting the rawhide. He could also run like a deer and covered a lot of ground from his center field position. Haas also exchanged “I do’s” with the former Marie Stucky of Caldwell, New Jersey. They had one child, a son, George Jr.

In 1925, Haas found himself in another league, as he was assigned to Birmingham of the Southern Association. He hit .316 for the Barons, and shared the team lead in doubles (27) with Stuffy Stewart. It was in Birmingham that his moniker “Mule,” was given to him. Although the tale varies a bit, Haas summed up the story. “I hit the ball all over the ballpark one day, and this sportswriter [Zip Newman] said ‘my bat packed the kick of a mule,’ The nickname caught on and that was it.”8

Haas was recalled by the Pirates and made his major league debut on August 15, 1925, pinch-hitting for Max Carey in the sixth inning. He got aboard on a force play and came around to score for the Pirates’ only run in an 8-1 loss to Cincinnati. Pittsburgh won the World Series in 1925, besting the Senators in seven games. They were loaded with talent in the outfield, with Kiki Cuyler, Clyde Barnhart and Carey. For that reason, Haas was sold to Atlanta, and found himself back in the Southern Association.

Over the next two seasons, Haas roamed the outfield and continued to hit the league’s pitching. In 1927, Haas hit .323 and led the Crackers in doubles (34) and home runs (10), and tied for the team lead in triples (19). Drennan had been following Haas’s career even after he got the stiff arm from the youngster a few years before. Connie Mack was looking for an infusion of youth into his outfield. Drennan gave Mack two choices; Haas of Atlanta and Eddie Morgan of New Orleans. One of Mack’s former players, Frank Welch, was a teammate of Haas’s and played against Morgan. When Mack asked Welch for his opinion, Frank replied, “Right now, I prefer Haas to Morgan. Morgan is a very young player and you can’t tell how far he can go, but today Haas has it on him in every particular.”9 Based on the advice of Drennan and Welch, Mack purchased Haas for $10,000.

When Haas joined the club for the 1928 season, a – future member of the Hall of Fame offered him sound advice. “Before I came to the A’s, I always held my bat at the very end of the handle,” said Haas. “But Eddie Collins took me aside one day and showed me a new way to grip the bat. He shortened my grip and I began hitting pitches I used to only nick. I’ve been batting with a shortened grip ever since.”10 He bided his time on the bench, as he did not show much hitting early in the season with his new grip. On July 25, Ty Cobb was struck in the chest with a pitch, and Haas replaced him in the starting lineup. On August 22, the Athletics and Indians were tied up in a marathon game at Shibe Park. Johnny Miljus, a pitcher who employed the slow-pitch to keep batters off balance, had made Haas look foolish on a previous at-bat. But Haas stepped to the plate in the bottom of the 17th inning, and connected for a home run, giving the Athletics a 6-5 win. *

Mack was putting together a competitive club. The outfield was as good as any in the majors with Al Simmons, Haas and Miller. Jimmie Foxx played first base, Max Bishop was at the keystone position and Jimmy Dykes manned the hot corner. Cochrane had few peers at catcher. In 1928 they finished 2 ½ games behind the Yankees. Although they compiled a 98-55 record, their head-to-head record of 6-16 against the Bronx Bombers was reason enough for the A’s to land in second place.

But they would not be bridesmaids for the next three seasons, as Mack’s juggernaut won the American League flag three years in a row from 1929 through 1931. Haas had career highs in home runs (16), RBIs (82), hits (181), runs (115), doubles (41) and triples (9) in 1929. He would not come close to duplicating that output for the rest of his career.

But there were two other areas where Haas had excelled. One of those was the art of the sacrifice, as he led the A.L. in six of seven years (1930 -1936) in sacrifice hits. The other bit of expertise that he gave the Athletics was that of a bench jockey. “Well you can’t holler if you don’t have a good voice,” explained Haas. “You have to holler to be heard. First, you must have the vocal equipment. Second, a little finesse. You can’t get away with that rough stuff that used to be the real thing years ago. Third, you have to be a sort of student of all the players, and you must pick out little quirks. And you’ve got to be in on the gossip around the league. Little incidents can be built into juicy items for the jockey.”11

The Philadelphia Athletics met the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1930 World Series. They toppled Gabby Street’s bunch in six games behind Grove and Earnshaw, who each won two games. As good a hitter as Mule was in the regular season, he could not find the stroke in the post-season. Even though he got the big hits the year before against the Cubs, he batted a pedestrian-like .238. Against the Redbirds, his average sank to .111.

Haas hit a career-high .323 in 1931. He had two five-hit games. The first one was a Philadelphia-Cleveland slugfest won by the A’s, 15-10, on May 17. The second came almost a month later on June 19. This time they clobbered the Chisox, 10-4, at Comiskey Park. The Athletics went 69-20 through May, June and July, and coasted to their third pennant in 1931. The series was a rematch with the Cardinals, and this time around St. Louis bested the A’s in seven games. Haas again sputtered on offense, batting a woeful .130. The following season New York regained first place, outdistancing Philadelphia by 13 games in 1932.

In the midst of the Great Depression, attendance had declined. The A’s drew 405,500 in 1932. It was their lowest figure in eleven years. Mack viewed Foxx, Cochrane and Grove as his untouchable players, while the rest of the team carried a price tag. Mack had a premise about trading or selling ballplayers to other clubs. “None of the five ranking clubs in the league will ever be able to buy or trade with me for a player as long as I am a manager. They are always well-supplied with players and that is as strong as I want to see them.”12 After some haggling with the White Sox, Mack sent Simmons, Dykes and Mule to the Windy City for $150,000. Simmons and Haas said all the right things, acknowledging their respect for Mack and the realization that there was nothing personal. It was about Mack recouping money for his franchise.

Mack was right on target when describing his trading partners, as the White Sox were a second-division team in the A.L. While all three players played well, it was the lack of first-line pitching that was their downfall. Dykes became a player-manager in 1933, and acquired Earnshaw from the Athletics to try and bolster the staff, to no avail. “Haas is a retiring sort of player,” said Simmons. “He never has much to say, but he’s trying all the time. If he’s in a slump, he doesn’t worry. If he’s going good, he doesn’t get overconfident. I’d set him down as a good, steady ballplayer. Perhaps he’s slowed down a bit, but he can still move around with the best of ‘em in the outfield.”13

Simmons’s assessment of his fellow outfielder was right on target. From 1933 through 1936, Hass was a regular in the Sox lineup, first in center field, and then in right. He batted a solid .283 during these years. But the Sox acquired Dixie Walker on waivers from the Yankees in 1936. Walker was inserted in right field in 1937, pushing Haas to the infield as a backup first baseman. Mule was released after the 1937 season. He returned to the A’s in a substitute role in 1938,then retired with a .292 career batting average, 254 doubles, 45 triples, 43 home runs and 496 RBIs. As a center-fielder, Haas had a career fielding percentage of .984

After his major league career, Haas managed Oklahoma City of the Texas League. He returned to Chicago to join Dykes’s staff as a coach from 1940 to 1946. He returned to the minor leagues, managing Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League (1947), Montgomery of the Southeastern League (1948), and Fayetteville of the Carolina League (1949).

Haas returned to Montclair as athletic director at Fort Montclair, coaching the basketball and baseball teams. One of his players was future Yankee great Whitey Ford. Later in life, he worked as a pari-mutuel clerk at Monmouth Park. One of his co-workers at the racetrack was former pitcher Bullet Joe Bush. In 1974, Haas was driving down to New Orleans to visit his son, George. He suffered a minor stroke en route, but continued his trip. While visiting, he suffered a bigger stroke and collapsed. He passed away on June 30, 1974. He is interred at Immaculate Conception Cemetery in Montclair.

Mule Haas was well-known as a creative and loud bench jockey. But he wasn’t always that way. “I wasn’t always gabby on the bench,” said Haas. “When I had those trials with the Pirates, I used to keep my mouth shut. In fact, one day years later when I bumped into Bill McKechnie [his old Pirates manager], he said to me, ‘Do you talk yet?’”14

One of his favorite foils was Boston slugger Ted Williams. “Ted didn’t have much of a sense of humor when it came to a riding from the opposing bench,” said Mule. “We really got on him after he gave an interview saying he once considered being a fireman. Well, every time he came up, we’d sound off like sirens and bang on any pipes in the dugout. That used to get him.”15

Notes

1 Roscoe McGowan, New York Times, “Cubs Attribute Defeat to Breaks”, October 13, 1929: 8s

2 Ibid

3 Norman L. Macht, Connie Mack: The Turbulent & Triumphant Years, 1915-1931, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2012, 550

4 Roscoe McGowan, New York Times, “Happy Fans Storm Athletics’ Heroes, October 15, 1929: 24

5 David M. Jordan, The Athletics of Philadelphia, McFarland and Company, Jefferson N.C., 1999, 105

6 National Baseball Hall of Fame, Player’s File

7 Bill Dooly, Sporting News, “Mule Haas, Who Started Speaker On His Way Out, Credited With Putting Macks in Championship Class”, December 5, 1929: 5

8 Sporting News, Obituaries, July 20, 1974: 45

9 National Baseball Hall of Fame, Player’s File

10 Dooly

11 Taylor Spink, Sporting News, “Mule Haas-Maestro of the Hee-Haw”, September 19, 1940: 4

12 Norman L. Macht, Connie Mack And His Final Years 1932-1956: The Grand Old Man of Baseball, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2015,18

13 Ed Prell, Chicago American, “Dykes, Haas to Aid Sox, Says Al”, National Baseball Hall of Fame Player’s File

14 Sporting News, Obituaries, July 20, 1974: 45

15 Ibid

Full Name

George William Haas

Born

October 15, 1903 at Montclair, NJ (USA)

Died

June 30, 1974 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.