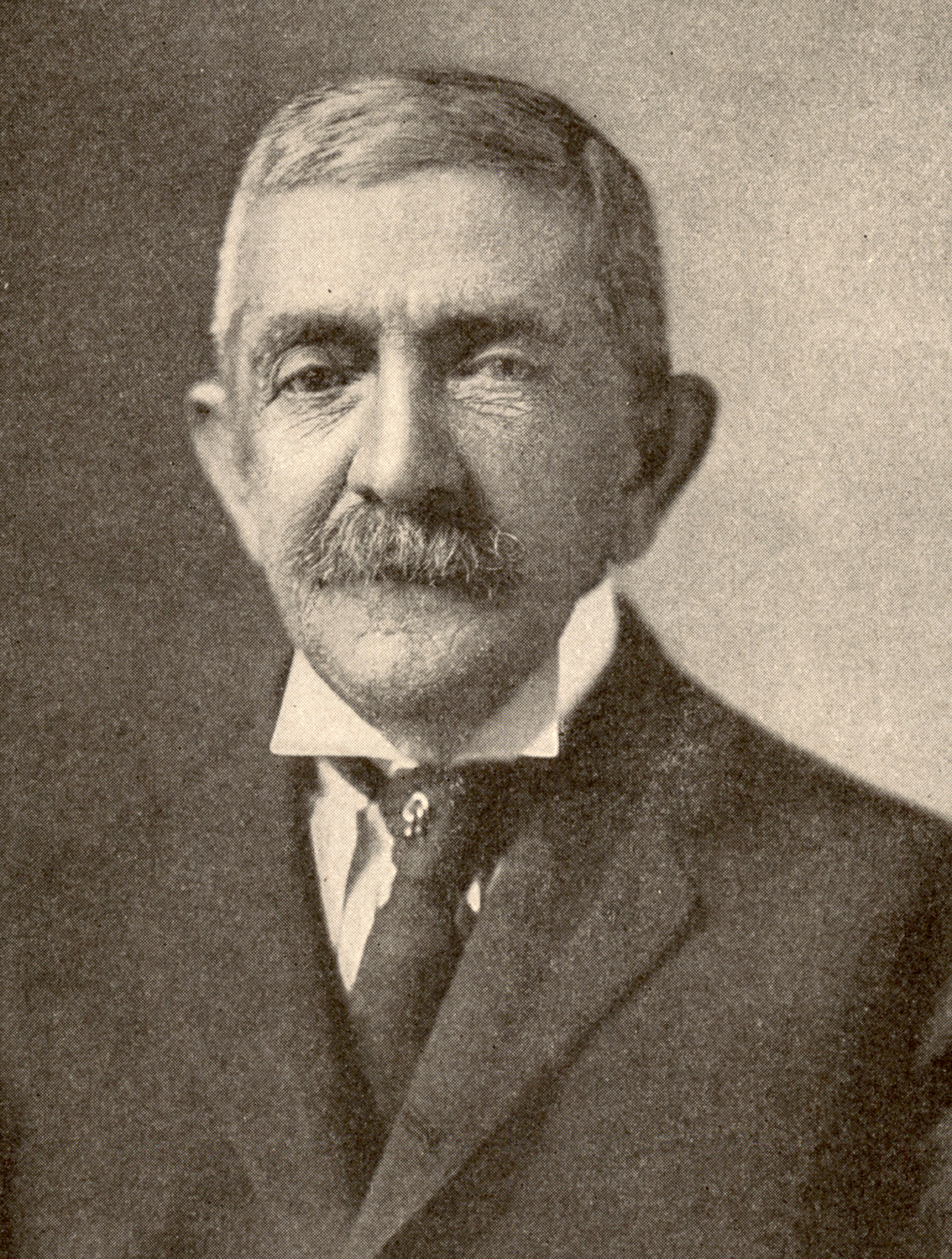

Nicholas Young

Nick Young’s baseball career illustrated important aspects of the game’s early development. He was a cricketer who took up baseball during Civil War service; afterward he joined a club of amateurs that grew increasingly competitive and came to include paid players. This evolved into helping organize the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, which led, in turn, to his taking executive positions with the National League. From social sport to prosperous business, he knew the game firsthand.

Nick Young’s baseball career illustrated important aspects of the game’s early development. He was a cricketer who took up baseball during Civil War service; afterward he joined a club of amateurs that grew increasingly competitive and came to include paid players. This evolved into helping organize the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, which led, in turn, to his taking executive positions with the National League. From social sport to prosperous business, he knew the game firsthand.

Nicholas Ephraim Young was born on September 12, 1840, into a large, well-to-do family about 50 miles northeast of Cooperstown. His father owned a saw mill and grain elevator and also was the Postmaster of Amsterdam, New York. In 1848 parents Almarin and Mary Ann Young bought Johnson Hall, a historic property near Amsterdam built in the 1760s by Britain’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Sir William Johnson. During the Revolutionary War the Loyalist owners fled to Canada and eventually the home was affordable for the Youngs. By then their Mohawk Valley area had become a carpet manufacturing center which drew workers from England. “The English weavers who were employed in our factories introduced the English game of cricket and we Americans took up their game,” Young recalled. He was a natural and before turning 21 made a select New York State team. “I played a number of games… and then came the Presidential Election of good Abraham Lincoln. . . [when] the great Civil War commenced, nearly all of our best cricketers responded to the call of their country.”1

In August 1862, Young volunteered at Amsterdam as a New York State infantry recruit for three years. According to the Registration Book he stood 5-feet-6; he had blue eyes and light hair. His occupation was listed as “grain dealer.” Immediately he was ordered to Washington, D.C., and was stationed at several fortifications protecting the nation’s capital. Taking a break the next spring, he played his first real baseball game. It was against another New York regiment, a couple of months before the Battle of Gettysburg, where Young was deployed in the defense of Little Round Top. The ballplayers’ ranks were mortally thinned, thus ending future games. Shortly thereafter he was transferred to the Army of the Potomac Signal Corps, remaining with that unit until mustering out on June 24, 1865.

Notably, his Civil War service involved another baseball twist. On July 12, 1864, at Fort Stevens, President Lincoln, Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and Private Young experienced to different degrees the Confederate attempt to take Washington. Young possibly signaled enemy troop movements; Lincoln and Holmes came under fire from sharpshooters during a severe skirmish, the President being ordered sternly by the Captain to take cover. Almost 60 years later, Justice Holmes would have gotten Young’s approval when he delivered the unanimous United States Supreme Court opinion that Major League Baseball did not violate federal antitrust law in Federal Base Ball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Clubs, 259 U.S. 200 (1922).

In late summer 1865, Washington became home for the rest of Young’s life. As a bachelor he moved frequently, from one downtown location to another. After marrying Mary Ellen Cross in 1872, the couple continued this transient pattern. With the birth of their third child, however, it was time to settle down. By 1883 they had become homeowners in the new District of Columbia suburb called Mount Pleasant. The development began just after the Civil War with New Englanders coming to work for the Federal Government and bringing their ideals of village life with them. They founded a Congregational Church (the Youngs later joined), also tended to have held antislavery views, and had come to favor the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Youngs’ address for over two decades was 1517 Howard Avenue. The home also doubled as National League headquarters. And their Mount Pleasant house was convenient to Fourteenth Street, N.W. transportation: horse cars, and then an electric railway, which ran to the U.S. Treasury Department, where Young was employed.

He worked there for slightly over 31 years, between August 1866 and September 1897. As a clerk in the Second Auditor’s Office, he settled individual accounts pertaining to pensions and other government disbursements. It had long been located in a building immediately west of the White House and just two blocks above the grounds where baseball was played by Young’s Treasury associates. In particular. those associates included Edmund Flagg French, a founder of the National Base Ball Club of Washington in 1859. Among gentlemanly rivals was the Olympic Club, formed seven years later. Young was invited to join the Olympics by a Treasury colleague and, as he related, “it was right there that my regular career in Base Ball started.”2 During the late ’60s and early ’70s he played right field for the Olympics; he became club manager in 1871.

At this time there were many Washington clubs, though none as esteemed as the Olympics and the Nationals. Two relegated to inferior status – not because of on-field performance or organizational shortcomings, but rather skin complexion – were the Alert Base Ball Club and the Mutual Base Ball Club. Charles Douglass, an army veteran and a government worker like Young, had helped put the clubs together and, for a fleeting moment, it seemed as though they might be treated equally. In 1867, the Mutuals scheduled home-and-home matches against the Philadelphia Pythians. This required arranging access to the Olympic/Nationals grounds. Permission was granted. But later that year the National Association of Base Ball Players, led by Nationals president Arthur Gorman, came out firmly against any integration. Somehow Young’s Olympics played Douglass’s Alerts and Mutuals in 1869, but there would be no more matches against clubs of color.3

Baseball was increasingly driven by business considerations, with Young a strong supporter. In 1871, he was directly involved in organizing the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players as a substitute for the fraternity-like National Association of Base Ball Players (1858), thus ending the last days of amateurism. His Olympic Club was an original member of the National Association and Young served as secretary of the first professional baseball league. The NA was still player-centered, however, and lacked overall authority. Young then joined in framing plans for a club-centered organization, the National League, which would be ready for the 1876 season. Its principal architect was William Hulbert; his trusted assistant was Nicholas Young, who consolidated drafts from the organizational meeting, the NL’s founding document. Their extraordinary rapport was evidenced by the Youngs’ naming their son Hulbert, born in 1877 when the two men directed the new league. His initial title was National league secretary-treasurer before moving up to league president in 1884.

Young became NL president as Organized Baseball – the National League and the American Association – was being challenged by the Union Association, an upstart eight-team league (that included a club adopting the name Washington Nationals) which defied the 1883 National Agreement. Most importantly, the UA refused to go along with the reserve clause giving clubs control over players’ freedom of movement. But the UA proved a failure on the field and at the box office, lasting for only a single season. In 1885, the reserve clause was modified somewhat in the interest of players, and the Nationals moved to the NL in 1886.

The mid-’80s marked an epochal period in the history of United States labor organizations and the attitudes of workers. The American Federation of Labor, founded in 1886, accepted the business order’s preeminence while demanding greater input concerning wages and working conditions. Basically, these aims were shared by the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, the game’s first union.

It certainly benefited from the respect accorded its president, John Montgomery Ward, an outstanding player with a law degree. When Brotherhood chapters spread throughout the National League, Young initially praised the organization. But when it started a separate league, that was going too far. Young fell into line with Chicago President Albert Spalding and his allies in suppressing the Players League. The owners retained control of the workplace, the Brotherhood passed out of existence, and Monte Ward conceded that baseball was a business.

President Young had already dealt with a challenging situation. In September 1885, soon after assuming office, the sixth-place Buffalo team was sold to the Detroit Wolverines, who were about as bad, but stood to improve instantly with the acquisition of Buffalo’s nucleus, future Hall of Famers Dan Brouthers and Deacon White, plus 19th-century stalwarts Hardy Richardson and Jack Rowe, dubbed “The Big Four.” This late-season transaction between two second-division teams might affect the outcome of the pennant race and drew immediate protest from New York Giants manager Jim Mutrie. Young acted quickly, notifying both clubs that such negotiations should wait until after the season; he voided the sale, directed the Buffalo ballplayers to return, and informed Detroit that any “Big Four” participation in games against contenders would result in forfeit. Detroit obeyed, and the matter was settled when their stars, having been released by Buffalo, chose to sit out the remaining three weeks of the season.4 Young’s decisive handling of the unprecedented issue proved successful.

More broadly, Young understood that the rules of the game are basic to entertainment appeal. He knew that periodically modifying official regulations was necessary to assure competitive balance. His tenure as president witnessed continuous rule changes and adoptions:

- Running starts by pitchers were eliminated;

- The pitcher’s box 55 feet from home was replaced by a mound and pitcher’s plate at a distance of 60 feet, six inches;

- Home plate became a rubber pentagon rather than a stone square;

- Four balls resulted in walks, and fouls were strikes; and

- Home team captains deciding if bad weather made field conditions unplayable became a thing of the past as umpires were given that

Umpiring had particular relevance to Young. He umpired NAPBBP championship games regularly in the early ’70s, when the Olympics were not involved. He did, however, work National Association games even though he might have had a direct interest in one of the teams. For the sake of what later would be termed umpire development, he started a Washington umpire’s school. As National League secretary-treasurer, he supported making umpires salaried employees beginning in 1883.

Young served as the National League chief executive for 17 years. None of his predecessors lasted longer than five. Most of his presidency was combined with being secretarytreasurer, a position he had held since 1876 that was not subdivided until 1896. Moreover, he was responsible for compiling and reporting statistics. He resigned from the Treasury Department in 1897 on account of his baseball workload. But making league leadership his full-time job did not result in continuing annual re-elections for long.

Turn-of-the-century club owners were divided over strategies to increase profits and who might be the best executive to achieve their economic goals. By the end of 1901, the issues had gotten so complex and machinations so involved that, to quote Harold Seymour, “the winter meetings of the National League [were] probably the most sensational in its history.”5 The election for president ended in a deadlock between Young, who was prepared to step aside but nonetheless backed by owners hoping to fashion a baseball trust, and Albert Spalding. Given the contentious stalemate, Young resigned, leaving him without official duties for the only time in the National League’s 26-year existence. A parting tribute to him was being made an honorary lifetime board of directors member.

In 1907, Young was associated with the commission on baseball’s origins chaired by his old Washington friend and former National League president, Abraham Mills. Arthur Gorman was another member who went back to D.C. club days. There is no evidence that Young contributed anything of substance to the Doubleday myth that emerged from the Commission’s report.

Young’s retirement period coincided with the arrival of the Washington Senators. “Uncle Nick,” as he was known, became a frequent fan at American League Park, and later, at Boundary Field, the enclosed wooden grandstand in the northwest section of the city that was closer to Mount Pleasant. But he began to suffer bad health, at one point applying to the Federal Government for an invalid pension. Then in 1914, the Washington Herald reported, “‘Uncle Nick’ will never see another game. He has become blind… illness has deprived him of his eyesight.”6

Two years later, at age 76, he died at the residence of his eldest son, Robert Young, nearby the family’s longtime Howard Avenue house which had once been the informal National League headquarters. His grave is in Rock Creek Cemetery, opposite the Washington, D.C. Soldiers’ Home.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Photo credit: Nicholas E. Young, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used:

https://www.ancestry.com/genealogy/records/nicholas-ephriam-young-24-3w4k.

Bealle, Morris A. The Washington Senators: An 87-Year History of the World’s Oldest Baseball Club and Most Incurable Fandom. Washington, D.C.: Columbia Publishing Company, 1947.

Beauchamp, Tanya Edwards. “The Mount Pleasant Historic District.” Historical Society of Washington, D.C., 2000.

Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia: 1865-1916.

Brown, Craig. Threads of Our Game website. https://www.threadsofourgame.com/

Ceresi, Frank and Carol McMains. “The Washington Nationals and the Development of America’s National Pastime.” Washington History, vol. 15, no. I (Spring/Summer 2003), 26-41.

Ceresi, Frank and Mark Rucker, with Carol McMains. Baseball in Washington, D.C.: Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002.

Cudmore, Bob. Baseball Pioneer from Amsterdam (June 6, 2020), www.rnohawkvalleyweb.com.

Edmund F. French Scrapbook and Memorabilia, 1859-1871, rns594. Special Collections. Kiplinger Research Library, DC History Center.

Federal Census, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910. National Archives and Records Administration.

Goldstein, Warren. Playing/or Keeps: A History of’ Early Baseball. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989.

Haupert, Michael. “William Hulbert.” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/william-hulbert/.

Horton, Ralph. “The Big Four Come to Detroit.” The National Pastime, No. 19 (SABR, 1999), 34-37.

Levine, Peter. A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball: The Promise of American Sport. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, 2nd ed. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2005.

Low, Linda and Howard Gillette Jr. “Mount Pleasant: Community in An Urban Setting.” Washington at Home”: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation’s Capital, ed., Kathryn Schneider Smith., 2nd. ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, 213-217.

Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals. New York: Walker and Company, 2006.

Mallinson, Jerry. “A.G. Mills.” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/a-g-mills/.

McKenna, Brian. “Arthur Soden.” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/arthur-soden/.

McKenna, Brian. “Arthur P. Gorman.” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/arthur-p-gorman/.

Nemec, David. The Rules of Baseball: An Anecdotal Look at the Rules of Baseball and How They Came to Be (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994).

Pestana, Mark. “1872 Winter Meetings: Inconsistencies and Ineligibles,” Baseball’s 19th Century Winter Meetings, 1857-1900. Jeremy K. Hodges and Bill Nowlin, eds. (SABR, 2018).

Povich, Shirley. The Washington Senators (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1954).

Register of Employees, 2nd Auditor’s Office, U.S. Treasury Department, RG217. National Archives and Records Administration.

SABR Baseball Graves Map. https://fortress.maptive.com/ver4/SABRGravesMap. Accessed July 8, 2025.

Schiff, Andrew J. “The Father of Baseball”: A Biography of Henry Chadwick (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2008).

Swanson, Ryan A. When Baseball Went White: Reconstruction, Reconciliation, and Dreams of a National Pastime (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

Thom, John. Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

Thom, John. “History Awakens: February 2, 1876 and the Founding of the National League.” Our Game, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/history-awakens-february-2-1876-and-the-founding-of-the-national-league-ab2ef2dae954.

Tygiel, Jules. Past Time: Baseball as History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Voigt, David Quentin. American Baseball: From Gentleman’s Sport to the Commissioner System, vol. 1 (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1983).

Young, Nicholas E. Military Service Record. National Archives and Records Administration.

Young, Nicholas E. Pension Payment Cards. National Archives and Records Administration.

Notes

1 N.E. Young, “Copy of Record of Various Incidents Especially Concerning Baseball,” 2-4, Nicholas Young Player File, National Baseball library.

2 N.E. Young, “Copy of Record of Various Incidents Especially Concerning Baseball,” 17, Nicholas Young Player File, National Baseball library.

3 Ryan A. Swanson, “Jim Crow on Deck: Baseball During America’s Reconstruction” {PhD Diss., Georgetown University, 2008}, chap.6.

4 Following the signing of a new National Agreement, the status of Brouthers, White, Richardson and Rowe was settled by a three-member committee headed by Young that assigned the four players to Detroit.

5 Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960), 317.

6 William Peet, ‘”Uncle Nick’ Young Has Seen His Last Game,” Washington Herald, February 4, 1914, 9.

Full Name

Nicholas Ephraim Young

Born

September 12, 1840 at Amsterdam, NY (US)

Died

October 31, 1916 at Washington, DC (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.