✩ 1922 ✩

Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v.

National League of Professional Baseball Clubs

Introduction

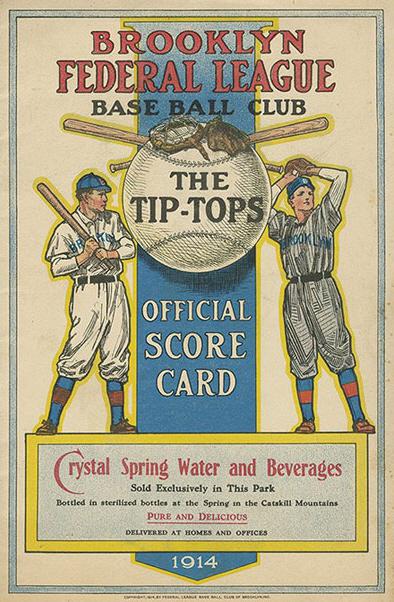

Heading into the 1914 season, the Federal League declared itself a third major league — on par with the American and National Leagues. Organized Baseball fought back ferociously, offering players more money to keep them from jumping to the new league, telling players the Federals were doomed to failure, and threatening to blacklist them if they switched. After battling for two seasons, the Feds gave up. A couple of franchises were bankrupt; those that weren’t received a buyout from the major league owners.

One FL franchise, however, held out. The Baltimore owners did not want a buyout; they wanted major league baseball in their city. When the major league owners ignored their pleas, the Baltimore shareholders sued Organized Baseball and their fellow FL owners. At the initial trial, the jury ruled in favor of Baltimore. Clearly, many of Organized Baseball’s actions violated antitrust laws; if the law applied to baseball, they were surely guilty. The jury awarded the Baltimore Federals $80,000 in damages; under the Sherman Antitrust Act provisions, the award was trebled and the plaintiffs awarded attorneys’ fees for a total of $254,000.

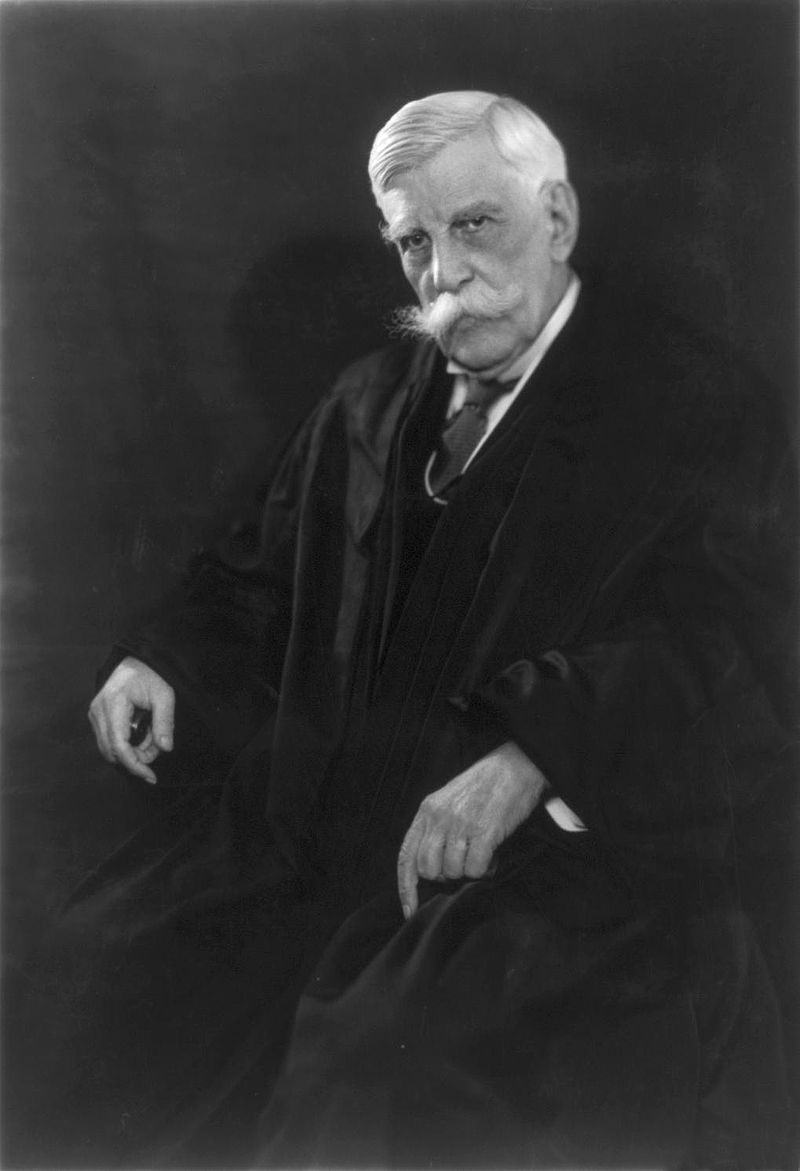

Organized Baseball appealed, and in 1920 the appellate court ruled in their favor. Now Baltimore appealed, this time to the US Supreme Court. In 1922, that Court, led by justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, upheld the appellate court’s decision, 9-0.

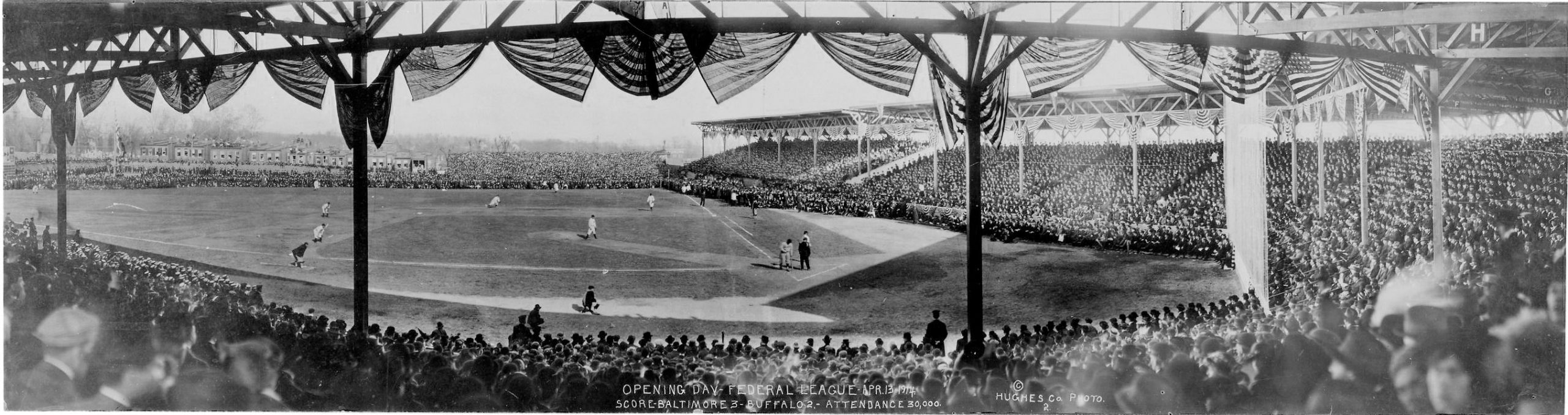

Baltimore’s Terrapin Park hosted Opening Day of the Federal League season on April 13, 1914. The Terrapins defeated visiting Buffalo, 3-2. (Courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles.)

Baltimore’s Terrapin Park hosted Opening Day of the Federal League season on April 13, 1914. The Terrapins defeated visiting Buffalo, 3-2. (Courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles.)

Although the principal plaintiff in the suit was the Baltimore stockholders, the decision had a far-reaching effect on the course of sports business in general during the remainder of the twentieth century. Despite two further Supreme Court challenges, and occasional congressional attempts to place baseball under the antitrust statutes, baseball remained exempt.

The question remains, did it matter? Would baseball have evolved differently had the Court determined that baseball was subject to the antitrust laws?

In the wake of Justice Holmes’s opinion, professional football, basketball, and ice hockey conveniently presumed the antitrust exemption covered them as well. For example, all the leagues had rules in place that effectively prevented players from becoming free agents at the end of their contract. When the Supreme Court ruled in 1957, in Radovich v. National Football League, that the antitrust exemption for baseball was an anomaly and not transferable to other professional sports, it did little to free up the players in those other sports. The owners of professional football, basketball, and hockey teams quickly instituted other expedients to blunt the decision’s impact.

The players in these other sports did benefit indirectly, however, from the emergence of rival leagues, something that did not happen successfully in baseball. The antitrust laws found by the courts to apply to these other sports discouraged (or at least tempered) many of the more blatant tactics used by Organized Baseball to wreck the Federal League, and successful challengers emerged in all three sports. And while none of them lasted longer than ten years, several ended with a merger of some sort in which the established league accepted all — as in the case of the American Football League — or at least some of the competing league’s teams. The existence of these rival leagues benefited the players as the competition for their services increased the number of jobs and drove up salaries.

With its 1922 antitrust exemption, baseball was effectively immune from competition from upstart leagues. Since the demise of the Federals, no rival has ever emerged to challenge major league baseball on the field. Had the court ruled against Organized Baseball in 1922 and put them under the same antitrust statutes as other professional sports, they would almost surely have faced additional competitive threats and likely another on-field competitor. The outcome could very well have been major league teams in the South and West many years earlier and higher player salaries as rival leagues competed for their services.

The minor leagues, too, would have turned out differently. It’s hard to envision the farm system, in which major-league teams gained control of minor-league teams, developing as it did, unless (as happened) baseball was protected from antitrust laws. Rather than losing their independence in the 1930s and 1940s as the farm system arrangement evolved, the minor leagues might have remained self-sufficient and unallied with particular major-league teams.

With the end of the Federal League and the subsequent antitrust exemption, Organized Baseball was free to develop as it did. The reserve clause remained unchanged for more than 50 years. The evolution of the farm system, beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, and the ossification of the franchise landscape (no team would move until 1953, and expansion would have to wait until 1961) could occur without fear of antitrust challenges. After the 1922 Supreme Court ruling and subsequent affirmations, Organized Baseball gained immunity from outside competition for many years to come.

— Daniel R. Levitt

Timeline compiled by Tim Odzer. Source: Nathaniel Grow, Baseball On Trial: The Origin of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014).

The Outlaw League

The Federal League formed in 1913 as an outlaw league in six cities across the Midwest. For 1914, it organized into an eight-team league with a more national presence and President James Gilmore declared it to be a major league, challenging the supremacy of the existing American and National Leagues.

For the Federal League’s two years of existence, 1914 and 1915, Gilmore tried to sell the public on the new league, attract well-heeled owners, negotiate a détente with the established major leagues, and sign the game’s top players. The Federal League eventually signed 81 major leaguers and 140 minor leaguers to contracts, nearly all of them at much higher salaries.

Despite these efforts, the Federal League folded after the 1915 season.

- Read more: James Gilmore’s SABR biography, by Daniel R. Levitt

- Read more: Find more biographies from SABR’s Whales, Terriers, and Terrapins: The Federal League 1914-15

- Read more: Find all published stories on Federal League games from the SABR Games Project

- Read more: “Federal League Baseball Cards,” by John Racanelli and Nick Vossbrink

Legal Proceedings

Before the Federal League was disbanded, it filed a lawsuit against Organized Baseball in the Northern District of Illinois. The complaint, filed after the league’s 1914 season, named as defendants the National League, the American League, all sixteen club presidents, and the National Commission. The plaintiffs alleged that the defendants had monopolized and conspired to monopolize the business of giving baseball exhibitions, in violation of the Sherman Act. They also alleged that the National Agreement amounted to a contract in restraint of trade.

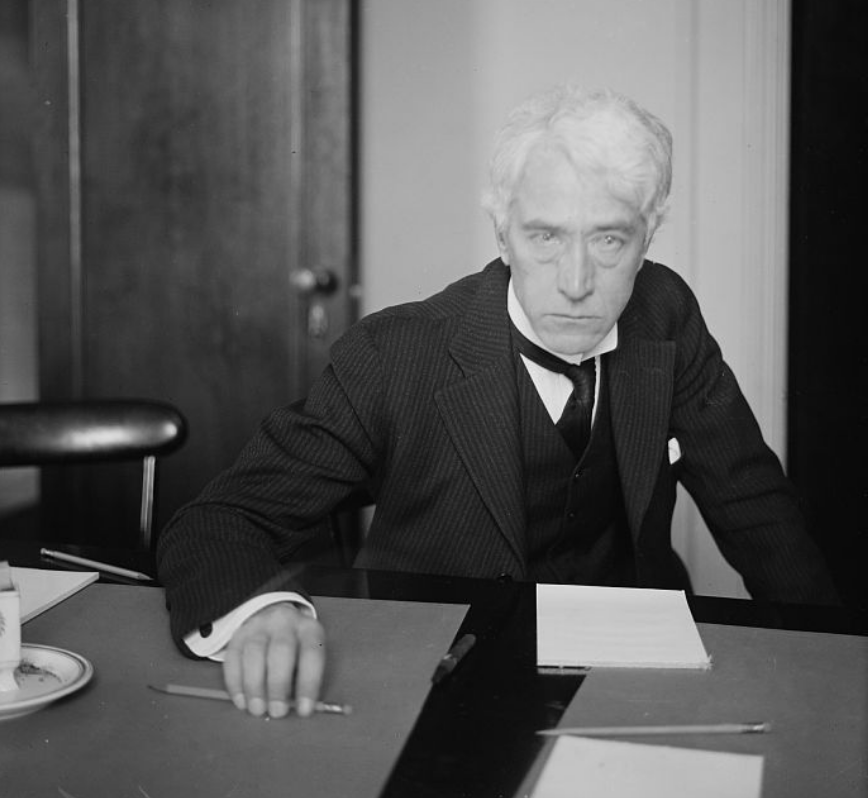

The case landed in the courtroom of District Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a Theodore Roosevelt appointee and a keen baseball fan with a reputation for trust-busting. Landis, however, was concerned that a decision adverse to the major leagues would undermine the game. During trial, he declared from the bench that “‘any blows at . . . baseball would be regarded by this court as a blow to a national institution.’”

Judge Landis never ruled on the case before him. It languished on his docket until the end of 1915, when the Cincinnati Peace Agreement ended the lawsuit, paid out more than $450,000 to Federal League owners, and also allowed owners Charlie Weeghman to buy the Chicago Cubs and Phil Ball to purchase the St. Louis Browns.

The SABR Business of Baseball Committee has made available more than 2,000 pages of scanned documents from the original filing of the 1915 Federal League lawsuit against Organized Baseball.

The digital archive of this US District Court case, Federal League v. National League, et al., represents a truly unique collection of documents challenging the authority of Organized Baseball during the Deadball, pre-World War I era. The case was foundational in the sense that while no judgment was rendered, it provided the impetus for future federal cases that ultimately led to the famous, or infamous depending upon one’s perspective, ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court exempting major league baseball from federal antitrust laws.

Road to the Supreme Court

When Federal League president James Gilmore negotiated a settlement with the National Commission in 1915, the Baltimore Terrapins were not included. Miffed at their own allies, Baltimore executives decided to file their own lawsuit, which went to a Washington, DC, jury in the spring of 1919.

Given the judge’s instructions to the jury — which, in essence, told the jury that Organized Baseball had in fact violated the federal antitrust laws, and that the Baltimore club was entitled to recover for any damages it suffered as a result — the verdict came as no surprise. The jury found in favor of the plaintiff and assessed damages at $80,000. The antitrust laws provide that guilty defendants pay three times the amount of the actual damages plus attorneys’ fees, so the final judgement was for $254,000.

In December 1920, the US District Court of Appeals reversed the verdict. Chief Justice Constantine J. Smyth wrote, “The players, it is true, travel from place to place in interstate commerce, but they are not the game …”

The Baltimore club tried to persuade the United States Supreme Court to reinstate the original verdict in its favor. But Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing for a unanimous Court, upheld the appeals court’s decision.

- Read more: “Anatomy of a Murder: The Federal League and the Courts,” by Gary Hailey