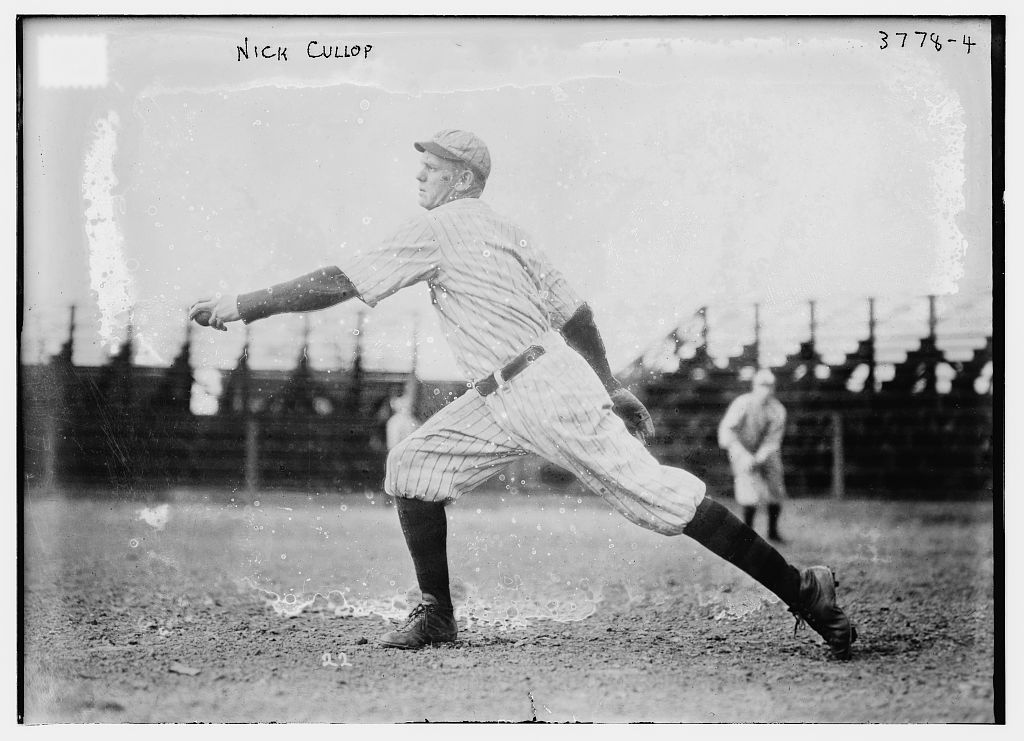

Nick Cullop (Norman)

Pitcher Nick Cullop had already turned in two strong seasons in the minors, but it was his performance in Cuba in the fall of 1912 that cemented his reputation. A group of New Orleans Pelicans players augmented with Heinie Groh went to Cuba for a 12-game series. They only won four of them; those were the games that lefty Nick Cullop pitched. Included in his four wins was a 12-inning no-hitter hailed as a “Cuban record.”1

Pitcher Nick Cullop had already turned in two strong seasons in the minors, but it was his performance in Cuba in the fall of 1912 that cemented his reputation. A group of New Orleans Pelicans players augmented with Heinie Groh went to Cuba for a 12-game series. They only won four of them; those were the games that lefty Nick Cullop pitched. Included in his four wins was a 12-inning no-hitter hailed as a “Cuban record.”1

Cullop always maintained that he was not a superstitious person. But a story about his no-hitter could easily have changed his mind. The story goes that after sightseeing at the Morro castle in Havana, Cullop met a fortune teller. Persuaded by teammates to have a “reading,” Cullop was told that the following day would be” the most eventful of his career,” but only if he had a gold coin in his pocket. The tale continues that Cullop had a gold coin to give to the hotel staff as a tip the next day but forgot to do so. Consequently, he had gold in his pocket when the no-hitter occurred.2

Norman Andrew Cullop was the last of six children born to Elizabeth Edwards (Heninger) and Stephen Norman Cullop. He joined the family on September 17, 1887 on the 50-acre, family farm near the town of Chilhowie, Virginia. The farm lay in Smyth County which is in southwestern Virginia. Growing up, Cullop attended school in Chilhowie. He graduated and a few years later attended King College in Bristol, Tennessee. He played baseball and was a member of the Young Men’s Christian Association. He also served as vice president of the Virginia Club. He left school after two years for a career in baseball.

The origin of “Nick” is unknown. The Sporting News said, “Norman Cullop, known to all the fans as “Nick”, though none call tell you why.”3 A search of newspapers reveals that “Nick” first appeared in 1912. Before that he was referred to as Norman. In 1920 a case of mistaken identity caused a young right-handed pitcher in the South Dakota League to be labeled “Nick” by newspapermen. The nickname stuck to Henry “Nick” Cullop who had a lengthy career as a player and manager.

Cullop told a writer that, “My ambition was to be an athlete. At 12 I was a good horseback rider. The thing that most interested me was throwing stones. I practiced until my arm was deadly and it was the beginning of my force as a pitcher.”4 He boasted he could kill a chicken at 75 yards with a stone. He played baseball as a youth in Chilhowie. He joined the semi-pro ranks with a team from North Halston after high school.

He ventured out on his own to the nearby town of Saltville. He worked in the salt mill, lived in a boarding home and pitched for the local team. He earned a reputation by beating the Bristol YMCA and then followed that up with two wins over Milligan College. Word reached Frank Moffett and he added Cullop to the 1910 Knoxville Appalachians in the Class D Southeastern League.

The season began in June with Knoxville starting slowly. They were 10-13 before Moffett found all the right pieces to the line-up. The team was 40-17 after that to finish in first place. Clyde Justice, president of the Asheville team, selected a league all-star team after the season. Cullop was the only Knoxville player selected as Justice chose six men who had spent part or all of the year with fifth-place Asheville.5Amongst Cullop’s accomplishment was a double header victory over Asheville on July 22. He won 7-2 and 2-0.

Knoxville shifted to the Class D Appalachian League in 1911 with many of the same players as 1910 with the notable addition of Dixie Davis to the pitching staff. Knoxville contended for the crown. Cullop won his first nine starts, but then fell into a losing streak. Manager Moffett sold him to last-place Bristol on August 11 for $100.6 Knoxville finished second by a game-and-a-half.

Cullop returned to form in Bristol. According to final statistics in Sporting Life, he led the league with 18 wins. He fanned 135 while walking only 38. He also fielded his position well, leading all pitchers with 78 assists. Two different groups chose all-star teams and Cullop was on both.

Returning to Bristol in 1912, he helped the Boosters go from worst to first as they edged Knoxville by two games. Cullop won 14 in 183 innings before he was sent to the New Orleans Pelicans late in the season. He appeared in five games for the Pels with a 2-2-1 record. He won his August 13 debut 8-1 over Atlanta.

Cullop headed to Cuba after the season. Now grown to 5-foot-11-inches and weighing 170 pounds he found his curveball to be an effective weapon on the island. “Give ‘em a fast one or a slow one and they’ll sure knock it a mile. But mix…with curves and you sure got them guessing.”7As noted he won four games. In his November 3 no-hitter, he issued four walks over the dozen innings. Upon his return from Cuba, Cullop wintered in New Orleans and prepared for spring training.

The Cleveland Naps had purchased the rights to Cullop from Bristol for $1000. They then optioned his contract to New Orleans. Over the winter the Naps transferred Bert Brenner, Jack Kibble and others to New Orleans because of their working relationship. “An enthusiastic scribe” figured the salaries for these men and decided that Cullop was a $25,000 addition to Cleveland’s roster. The scribe incorrectly assumed the transfer of players constituted a trade for Cullop.8

The $25,000 figure found its way into newspapers and put dollar signs in Cullop’s eyes. When his first contract arrived, he refused to sign and returned home. “I may be found husking corn at home. I have not yet found a day when we did not live comfortably at home and while I am anxious to continue as a pitcher, I do not feel that I should accept the terms unless they are satisfactory.”9

Training camp opened in Pensacola, Florida and Cullop remained in Virginia. Cleveland dispatched scout Billy Doyle to try to rectify the situation. He enlisted the aid of Red Munson who had managed Bristol in 1912. Between the efforts of Doyle and Munson, Cullop was persuaded to sign for the original amount and report to camp. He arrived March 14.

All the publicity put Cullop under the microscope and he responded well. He showed the writers that he had good form on the mound. They were also pleased with his knowledge of the game and his duties backing up bases. He got his first exhibition work at Mobile on March 19 and worked an inning and a third. He followed that up with four innings of work the next day, again drawing praise. Late in spring training he injured his back making a fielding play. This delayed his major-league debut.

The season opened April 11 and Cullop was cleared for action a few days later. Cullop was not one for superstition, but manager Joe Birmingham was. He warmed Cullop up in relief in Chicago, but then did not use him. The Naps won. The next time he warmed up Cullop the Naps won again. Cullop noted, “I must be a mascot. The club always wins when I warm up.” Birmingham even mused he could warm him up “every day from now until the season is over.”10

Cullop was finally sent to the mound on May 5 in an exhibition with the Pirates. As the starting pitcher he was up 5-0 before surrendering a two-run double to Honus Wagner. Cullop left the game ahead 5-4, but the Pirates rallied to win in the ninth. He made his major-league debut finally on May 20 in a wild affair against Washington. Cullop entered the game in the third as Cleveland’s third pitcher with the Naps down 4-2. He gave up 2 runs in the third and another 2 in the sixth. He left the game trailing 8-5, but the Naps rallied for a 10-9 victory. He struck out in his lone at bat.

He made two more relief appearances before getting his first start on June 25 in Detroit. He twirled seven innings in a 4-2 loss. Birmingham was pleased with the performance and announced Cullop would start in the Chicago series. Plans changed and Cullop’s next appearance was July 4 versus the Tigers in the second game of the twinbill. He entered the game in the seventh in relief of Vean Gregg with the Naps down 2-0. Cleveland staged a rally in the eighth to win 4-2. Cullop allowed one hit (to Del Gainer, who had homered off Cullop in the June 25 game) to even his record at 1-1.

He was given the start the next day in a game that ended in a tie. On August 1, he recorded his first complete game with a 6-2 win in Boston. Used as a spot starter and mop-up after that, he made 14 more appearances, all in losing causes. He started and won on October 4 against the Browns. He closed out his first season 3-6. The fine K/BB ratio he exhibited in the minors disappeared as he issued 35 walks in 97 innings while striking out 32.

Coming from rural Virginia, Cullop had a reputation as a “Rube.” It was hinted that he paid for elevator rides on more than one occasion. The veterans played other well-worn tricks on him. When the Naps made their first visit to New York he spent hours walking the city on his own self-guided tour. Despite the reputation, he had a good head on his shoulders in matters of money. Money became readily available in 1914 because of the birth of the Federal League. Cullop would take advantage of the climate.

On December 24, 1913, Cullop eloped with Pauline Dungan, “a pretty Virginia blonde.” She was the daughter of a Smyth County farmer. The couple drove to Bristol, Virginia for the surprise nuptials.11Cullop went to spring training in Athens, Georgia accompanied by his new bride. He made the roster and was sent into relieve on April 21 in Detroit. He allowed three runs, only one was earned, in the 7-4 loss. A week later he was optioned to the Cleveland AA franchise. Cullop felt betrayed by management. The next day he signed a two-year contract with the Kansas City Packers in the Federal League.12

Manager George Stovall put Cullop to work immediately. He dropped his first start 3-0 to Baltimore. He won the next 3-2. That was indicative of his season, up and down. He finished at 14-19 with a 2.35 ERA. He authored four shutouts, twice beating the Pittsburgh Rebels 1-0. The Packers finished in sixth place.

In 1915 the Packers added Johnny Rawlings at shortstop and Alex Main to the rotation. The team climbed to fourth place. Cullop led the team in wins (22), complete games (22) and innings pitched (302). Once again, he twice shutout Pittsburgh 1-0. He was third in wins in the league and eighth in ERA (2.44).

Cullop became the property of the New York Yankees over the winter. New York was managed by Bill Donovan and was in desperate need of left-handed pitching. They had gotten 62 innings and two wins from their lefties in 1915. Cullop started the season in the bullpen. He picked up a win on April 29 with two sparkling innings of relief against the Athletics. One of the batters he faced that day was catcher Billy Meyer. Meyer had been Cullop’s first catcher in Knoxville. The pair would later team for many years on the Louisville Colonels. Meyer often claimed he could have caught Cullop from a rocking chair.

Cullop got his first start on May 11 against the White Sox. He responded with a three-hit, 2-1 victory. He did not lose a game for the next two months. His record stood at 9-0 even though he missed a turn in the rotation with a strained chest muscle. He finally tasted defeat on July 14 versus the Tigers. He and Willie Mitchell went into the 12th inning tied 2-2. In the top half, Cullop yielded four singles and an error to lose 6-2. He won three more before losing to the Browns on August 25.

The magic was gone. Detroit pounded him in his next outing. In September the Yankee offense only plated five runs in his three losses. He closed out the season 13-6 with a 2.05 ERA. The Yankees finished in fourth.

Cullop did not make the rotation the following year. He had a tender elbow that would bother him the whole season. From May 8 to June 5, he had four starts, all complete games. Five winless efforts followed before he was relegated to the bullpen. One of his few late-seasons starts came September 11 in Philadelphia; he authored a 1-0 victory for the highlight of his season. He closed out the year 5-9 with a 3.32 ERA. In January, the Yankees packaged him with four other players and $15,000 to secure Eddie Plank and Del Pratt from the St. Louis Browns.

The Browns tried diligently to come to terms with Cullop, but the two parties never agreed on a contract. Cullop stayed on the Virginia farm in 1918-19. One writer hinted that the elbow injury had caused Cullop to lose confidence in himself.13He did start to play some semi-pro later in 1918. In 1919 he seemed to have regained his strength and could be found playing all around the coalfields. On December 21, 1919, Salt Lake City in the PCL purchased his rights from the Browns for $3500.

Cullop reported late to Utah because of an illness. It then took nearly a month for him to work into shape. His first two starts were shutout victories, but on May 6 he walked off the mound to protest the calls of umpire Mal Eason.14Cullop left the Bees and joined an outlaw team in Wellsville, Utah that played in the Cache Valley League. He was enticed with a contract offer of $3500.15

Salt Lake president William Lane wasted no time. He went into federal court and obtained an injunction restraining Cullop from playing with any team besides the Bees. More importantly he filed a $10,000 suit against the Wellsville franchise claiming that was the value of Cullop to his team.16Cullop returned to Salt Lake City and pitched May 26 in Seattle. He allowed six hits in a 4-1 Bees win.

The Bees finished second in the pennant race, but Cullop had a so-so year. He was fourth in wins, second in ERA, fifth in innings and sixth in WHIP for the team. He was sold back to the Browns and was one of 19 pitchers who went to spring training. He was the oldest pitcher to make the trip north. He made four appearances, one of them a start. In 11 and two-thirds innings he surrendered 18 hits and 11 earned runs. In his final major-league season, he was 0-2 with an 8.49 ERA. The Louisville Colonels in the AA picked him up.

Joining the Colonels revived Cullop’s career. Manager Joe McCarthy added him to a rotation including Ben Tincup and Ernie Koob. They won the league title and took on International League champion Baltimore in the Junior World Series. The Orioles were heavy favorites, but Cullop pitched a brilliant first game while the Colonels pounded Lefty Grove from the mound in a 16-1 win. The Colonels took the series five games to three. Cullop was 1-1 in four appearances.

The Colonels missed out on the pennant in the next three seasons. It was not for lack of effort on Cullop’s part. He was chosen opening day pitcher from 1922-26 and turned in a victory each time. The Colonels added a 32-year old outfielder named Joe Guyon in 1925. He led the league in hits with 228 and batting at .363. Cullop took advantage of the added offense to win 22 games, his most in the minors. It tied him for second in the league helping Louisville to the pennant.

The Junior World Series was again a match between Louisville and Baltimore. This time Cullop lost the opener and Baltimore came out on top five games to three. Following that series, the Colonels went to San Francisco for another best-of -nine match. Cullop faced off with Willie Mitchell in Games 3 and 7. The pair split with Cullop winning Game 7. He lost Game 9 in relief.

In 1926, Cullop’s longtime teammate and friend Billy Meyer took over as manager. Cullop won 20 games and the team captured the crown. This time the Colonels were matched with the Toronto Maple Leafs in the post-season. The Canadians swept the series with Cullop taking one of the losses.

That was Cullop’s last hurrah. Now in his late 30s, he was given a diminished role on the team in 1927-28 cutting his innings to 142 and 110. Somehow, though, the name “Nick Cullop” was appearing in sports sections more than ever. This was partly because Henry “Nick” Cullop had developed into a home run hitter. But the name also appeared in racing forms because the owner of the Louisville Colonels, William H. Knebelkamp, named a race horse after Norman “Nick” Cullop. It was a tribute to Cullop’s long service with the team. The trainer contemplated entering the steed in the Kentucky Derby in 1928 but decided to enter him on the undercard instead.17

Cullop made six relief appearances for Louisville in 1929. His last appearance on a field was as acting manager after Allan Sothoron and Ben Tincup had been ejected in the May 12 game at Minneapolis. Cullop was ejected in the ninth for arguing ball and strike calls. Ten days later he was transferred to the Dayton Aviators in the Class B Central League. At that time, he told the paper, “My life had been devoted to two occupations, baseball and farming, and when I say “baseball” I mean as a player. If I should ever become a manager, the job will have to seek me, for I will never seek the job.”18

The Dayton Aviators were managed by longtime Louisville teammate Merito Acosta. The Cuban outfielder was in his first season as manager and needed a veteran arm to help guide his teenagers. He was double the age of his bullpen mates, but Cullop made 25 appearances. In 138 innings, he posted a 7-9 record.

As fate would have it, a managerial job came looking for him. Cullop would have to find tenant farmers one last time as he accepted the offer to manage Dayton in 1930. The 1929 team had seven players appear in over a hundred games. Five of them hit over .300 including future Hall of Famer Billy Herman. In a cruel twist, none of the .300 hitters returned. Short on talent, Cullop used 20-year old pitcher Johnny Marcum on the mound (6-9) and in the outfield (.421 in 88 games). The season opened May 1 versus Canton. The second game of the season was a monstrous 22-17 affair. The two teams amassed 36 hits and 13 errors. Aviators’ third baseman Jim Vorhoff made six of the errors.

Dayton fell to last place at the end of May. On August 15 in Richmond, Indiana, Cullop was rushed to the hospital. He underwent an emergency appendectomy forcing Verhoff to serve as manager until Cullop’s return. Nick took the mound one final time on September 5, pitching one uneventful inning.

Cullop had last spent a year on the farm in 1919. He settled peacefully into family and farm life. Pauline had given birth to two children, Norman (1917) and Elizabeth (1919). When Elizabeth married James Greever, they took over the farm in Smyth County. The other three family members moved to Jeffersonville in Tazewell County. When the son married, he and his wife lived with the Cullops. Nick served as a security guard for many years on a large estate; patrolling the grounds on horseback.19 He also worked for the Pocahontas Fuel Company. After suffering from emphysema for several years he died from a cerebral embolism on April 15, 1961. His body was returned to the Sulphur Springs Cemetery in Chilhowie for burial.

Sources

Thank you to Dana McMurray at King’s University (previously King College) for searching the old yearbooks for info on Cullop. Bob Bailey’s History of the Junior World Series was a useful source.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Sporting Life, November 23, 1912: 11.

2 “Big Event Predicted by Story Teller,” Plain Dealer, March 25, 1913: 10.

3 The Sporting News, December 9, 1920: 2.

4 “Develops Pitching Arm by Throwing Stones,” Plain Dealer, January 26, 1913: 17.

5 “Picks an All-Star Team from the Southeastern,” Asheville Citizens-Times, September 29, 1910: 3.

6 “Cullop Sells for $100 a Year Ago,” Plain Dealer, January 5, 1913: 2C.

7 “Nick Cullop Explains His Success in Cuba,” Plain Dealer, March 19, 1913: 10.

8 “Cold Facts Spoil Fairy Tale Woven Around Cullop’s Purchase; Cost Naps Only $1000,” Cleveland Leader, March 9, 1912.

9 “Cullop May Not Sign,” Plain Dealer, February 23, 1913: 1C.

10 “Cullop Warms Up, Naps Win; Nick Now Must Work Every Day,” Plain Dealer, April 21, 1913: 10.

11 “Nick Cullop Marries Pretty Virginia Belle,” The Tampa Tribune, January 4, 1914: 22.

12 “Nick Cullop Jumps Cleveland and Signs with Kay See Feds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 1, 1914: 6.

13 The Sporting News, January 31, 1918: 1.

14 “Outlaws Threaten Disruption of Bees,” Salt Lake Telegram, May 10, 1920: 4.

15 “Diamond Dust,” Salt Lake Telegram, May 15, 1920: 8.

16 “He Curbed Outlawed Ball Clubs,” Salt Lake Telegram, May 24, 1920: 16.

17 “Leo Feeney to Have the Mount,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April10, 1928: 15.

18 Bruce Dudley, “Cullop to Help Acosta’s Team,” Courier-Journal (Louisville) May 22, 1929: 13-14.

19 “Nick Cullop Passes,” Courier-Journal, May 30, 1961: 20.

Full Name

Norman Andrew Cullop

Born

September 17, 1887 at Chilhowie, VA (USA)

Died

April 15, 1961 at Tazewell, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.