Omar Linares

Omar Linares is widely considered the best third baseman found anywhere in the world outside of the U.S. major leagues during much of the 1980s and 1990s. What Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard or Satchel Paige may have been to the first half of the 20th Century (potential national sporting icons barred from the big-league stage by racial politics), “El Niño” Linares similarly was to the century’s final decades (a sure-fire big-league star kept from baseball’s biggest stage by the fallout from Cold War politics). But the truly significant difference was that while Paige or Gibson would have jumped at the chance to be big leaguers yet had no power over their unjust exclusion, Linares repeatedly turned his back on big-league offers and personally chose to cast his lot with the Cuban socialist baseball system he so visibly represented and championed for two full decades.

Omar Linares is widely considered the best third baseman found anywhere in the world outside of the U.S. major leagues during much of the 1980s and 1990s. What Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard or Satchel Paige may have been to the first half of the 20th Century (potential national sporting icons barred from the big-league stage by racial politics), “El Niño” Linares similarly was to the century’s final decades (a sure-fire big-league star kept from baseball’s biggest stage by the fallout from Cold War politics). But the truly significant difference was that while Paige or Gibson would have jumped at the chance to be big leaguers yet had no power over their unjust exclusion, Linares repeatedly turned his back on big-league offers and personally chose to cast his lot with the Cuban socialist baseball system he so visibly represented and championed for two full decades.

Of course Linares’s decision came with a huge plus-minus factor. Cuba’s best modern-era player today remains at one and the same time both a true icon on his native island and a virtual unknown to North American fans – fans whose view is restricted narrowly to the realm of U.S. organized professional baseball. Indisputably the greatest all-around individual player in post-revolution Cuban League annals, the statuesque right-handed-swinging slugger today remains the holder of numerous Cuban League batting records (viz., highest lifetime batting average, second highest total home runs) as of 2011, nearly a decade after his retirement. Also a fifteen-year mainstay on Cuban national teams that dominated numerous international and Olympic tournaments in the fading years of the 20th century, Linares assumed near-legendary status in a branch of the sport that fell well outside the radar of an American press and fandom focused almost exclusively on the major league baseball scene.

Like a surprising number of modern-era Cuban ballplayers, Omar Linares likely inherited at least a degree of his obvious athletic talent from family bloodlines. Born on October 23, 1967, in the tobacco-rich province of Pinar del Río (in the small village of San Juan y Martínez at Cuba’s far western end), Omar was the first-born son of Fidel Linares (1931-2000) and Panchita Izquierdo Quintana. Omar’s father Fidel – a noteworthy ballplayer in his own right during the first decade of Cuba’s newly minted post revolution “National Series” baseball – was about to launch the seventh season of his own decade-long career at the time of his first son’s arrival. A second son, Juan Carlos, was born three years later (October 17, 1970) and would himself become a talented outfield teammate of his more famous sibling. Baseball passion indeed ran deep in the Linares clan, as it does for so many Cuban families.1

Fidel was himself beyond thirty years of age in 1962 when a newly installed revolutionary government closed down Cuba’s long-thriving professional baseball winter circuit and substituted an amateur four-team league (which would rapidly expand to a dozen clubs before the decade was out) in its place. A diminutive and pesky southpaw-batting outfielder, the elder Linares would build his own legacy in a handful of early National Series seasons that was far larger than anything explained by offensive numbers he left in the early league record books (10 seasons, 381 hits, with six homers). He did make a name for himself as a skilled if not prolific batsman (.275 career average) with the Occidentales ball club of the first few rather short league campaigns, and he does hold a special niche of his own at the dawn of league history. He was the base hits leader in National Series II (1963). He helped form a memorable outfield that also featured Erwin Walter (first-season batting champ) and Raúl González (owner of the same distinction in campaign number three). This was easily the best outfield trio of first-decade Cuban League action and also the backbone of an Occidentales team that under manager Fermín Guerra, a former big leaguer, earned the first league championship of novel post-revolution island baseball.

It would be a mistake to assume that Fidel Linares’s stature in Cuban League history consists solely in the act of siring two future Pinar del Río stars of decades to come. Linares senior celebrated his best individual campaign by hitting .310 in 1963, shadowing teammate Raúl González (.348) in the league batting race during only the second season of renovated amateur league play. He roamed center field between a pair of first-generation Cuban League legends, Miguel Cuevas (Orientales) and Pedro Chávez (Industriales), during that same year’s Pan American Games triumph earned in Brazil. Having first starred in the middle and late fifties in the popular Pedro Betancourt League—the first Cuban amateur circuit to admit black-skinned athletes on a large scale – most of Fidel Linares’s best years were likely already behind him before President Fidel Castro revamped island winter league play by substituting the National Series for the MLB-affiliated and strictly Havana-based professional circuit.

On celebratory opening day of the inaugural 1962 National Series season (an occasion marked by President Fidel Castro taking a ceremonial first swing in the batter’s box) it was a second Fidel (Linares) who captured a lasting measure of immortality among fans and historians alike. Linares Sr. smacked a crucial base knock in Estadio Latinoamericano (still known as Cerro Stadium at the time) to decide the first contest ever played in a league that would eventually celebrate its Golden Anniversary with the 2010-11 campaign. And such was the eventual stature of the ball-playing Linares family that when Fidel finally lost a lengthy and painful battle with cancer in mid-2000 his formal state-sponsored funeral staged in Pinar del Río Province became a celebrated national event seemingly more fitting for a military hero than a mere one-time popular baseball star.

Omar’s younger sibling, Juan Carlos, mirrored their father far more closely than did the celebrated elder son. Swinging from the left side of the dish, patrolling the outfield, and featuring an approach based more on finesse and speed than unparalleled power, Juan Carlos closed out his own 17-year Cuban League career in the spring of 2005, thus overlapping with Omar in the Pinar del Río lineup for a full fourteen domestic league seasons. While the career offensive numbers of the younger Linares hardly rival the output of his famed brother, they remain far more impressive than those of the pioneering father and do nothing to detract from the rich Linares family legacy. Juan Carlos would sport a hefty near-two-decade career batting average of .322, produce more than 1500 hits and better than 100 homers, and boast above 2200 total bases. Never a league all-star or even a candidate for national team selection, Juan Carlos did get to play alongside Omar on a pair of ultimately successful National Series championship teams (in 1997 and 1998).

Among the recent several generations of talented Cuban ballplayers Omar Linares stood out from the pack by the early 1990s as the “cover boy” for Cuban League baseball talent. Less than a half-dozen seasons into his own career, Omar was already being widely touted by pro scouts, fans of Olympic-style baseball, and the Cuban sports ministry propaganda machine as the best slugging infield prospect on the planet not already showcasing his wares in the major leagues. Those who saw him perform at the plate and in the field during his prime (between the 1987 Indianapolis Pan American Games and the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games) might easily make the defensible argument that there have been no obviously better all-around stars at the hot corner position over the past twenty-odd years, even on big-leagues ball clubs. And those impressions had as much to do with defensive agility and arm speed as they did with mere batting strength and clutch hitting savvy.

A muscular jet-black right-handed six-footer who played most of his career weighing between 205 and 215 pounds, Omar Linares first broke onto Cuba’s baseball scene in highly dramatic fashion, appearing on the 1982 national junior team roster at the remarkable age of only 14 and (despite his raw youth) batting a respectable if not eye-popping .250 during Juvenile World Championship games staged in Barquisimeto, Venezuela. That same fall of 1982 the super-talented novice infielder surfaced as an untested Cuban League rookie prospect boasting apparently unlimited promise, appearing in 27 games for the ball club named Vegueros (“Farm Workers” – the team representing Pinar del Río Province) before his sixteenth birthday. Two seasons later, during the Junior World Cup tournament in Kindersley, Canada – the almost-18-year-old “phenom” first stunned international observers by crushing 8 homers, blasting 7 additional extra base hits, and posting a remarkable .511 batting average to launch his soon burgeoning legend as perhaps the greatest world amateur tournament player of all time.

Elevated to senior national team status, Linares debuted at the Intercontinental Cup games in Edmonton in 1985, where he once more slugged away at a remarkable .467 clip for the nine-game tournament span. He soon also lit up the Central American Games competitions held in the Dominican Republic the following year when he pounded the ball once more at a .497 clip. That same season he posted yet another glowing .457 mark in his first World Cup Series (11 games) staged at Haarlem in The Netherlands. A single year later at the late-summer Pan American Games in Indianapolis (while still a teenager, though now also a fully seasoned international veteran) he maintained the remarkable momentum with an eye-popping .520 average (including a pair of triples) to outstrip the entire field of tournament sluggers, including potent future U.S. big leaguers such as Ty Griffin, Ed Sprague, and Tino Martinez. For an encore that same October the prodigal teenager smashed 11 homers during Intercontinental Cup matches in Havana as the still-loaded Cuban contingent again ran roughshod over a yet another talented Team USA lineup, one that boasted future major leaguers Mickey Morandini, Chuck Knoblauch and Scott Servais, and was mentored by University of Miami coaching legend Ron Fraser.

The exploding Omar Linares legacy grew largely from an amazing collection of unparalleled batting achievements which began in the 1980s and soon also stretched across the decade of the nineties. Twice, in 1990 and 1993, he batted over .400 for a full season that included both the longer National Series and shorter Selective Series campaigns; he completed four National Series schedules batting above the touchstone .400 plateau (admittedly all in the era of aluminum bats) and eventually reached 400-plus homers in only 1700 games and 5962 at-bats; his ratio of one round tripper every 14.8 official at-bats rates favorably against the most legendary big-league bashers. Using Total Baseball’s respected Home Run Average (homers per every 100 at-bats) as a yardstick, and comparing Linares to household-name major league stars – admittedly a futile albeit entertaining exercise – his 6.77 career mark would surpass (as of 2011) all but those of Mark McGwire, Babe Ruth, Barry Bonds, Jim Thome, Ralph Kiner, Harmon Killebrew and Sammy Sosa.

The frequency of various batting achievements compared to the related number of times at bat provides one of the best windows on the uniqueness of Omar’s Cuban League and international tournament performances. Linares biographer Juan Martínez (at the time of completing his study in 2000) calculated the Linares ratios as follows (including both Cuban League and international tournament games played): base hits (one for every 2.67 ABs), doubles (1/18.9 ABs), homers (1/13.66 ABs), RBI (1/4.66 ABs), walks (1/4.78 ABs), strikeouts (1/8.67 ABs). Most impressive here is the fact that Linares both homered and walked twice as frequently as he struck out. And in pressure-packed international events the Cuban slugger (admittedly against sometimes less than stellar opposing hurlers) homered more frequently than once every ten official trips to the plate (1/9.54 ABs).2

But the Linares reputation grows also from the uncanny ability to deliver in almost all tense clutch situations. In the slugfest 1996 Olympic gold medal shootout in Atlanta versus Japan, Linares saved the day with three booming homers, even after nearly proving a goat with his crucial early-game throwing error that had let Japan back into the contest. In the opening Team Cuba-Baltimore Orioles exhibition match in Havana (March 1999), despite coming off a season-long leg injury that had limited his National Series play to only 30 games, and despite the handicaps of hitting for the first time with wooden lumber and debuting against major league pitchers, Linares delivered a game-tying eighth-inning single. A month later in Baltimore, during Team Cuba’s 12-6 defeat of the major leaguers, the veteran slugger reached base in every plate appearance, recording three singles, a double, and a pair of walks.

After slumping badly throughout the Pan American Games in Winnipeg during late July-early August of that same year (hitting less than .200 for the entire event), Linares unloaded at just the right time with a vital homer in the do-or-die semifinal match versus Canada that clinched Cuba’s hard-earned qualification for the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney. The Winnipeg homer blasted off Canada’s Mike Meyers was one of the most important long-balls struck in recent Cuban national team history. Linares himself (in a recently published biography released during 2002 in Havana) recalls the Winnipeg circuit blast as his single brightest career moment, a landmark achievement among dozens and dozens of truly memorable clutch performances.3

Since stateside fans pay such sparse attention to non-big-league international tournament competitions, Linares had but few chances over the years to shine before North American audiences. The Indianapolis Pan Am Games came before his legend had grown to full proportions, while the 1999 appearance in Baltimore displayed a fading star well beyond his most productive years. For Linares the one grand moment staged before large audiences on American soil finally came during the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games tournament played in Fulton County Stadium. Before a 50,000-plus Sunday afternoon crowd Cuba defeated Team USA 10-8 in opening round action with Omar fully showcasing his long-rumored prowess. Linares opened the display of Cuban firepower with a first-inning solo shot against future big-league flame-thrower Billy Koch. For the nine-game event the Cuban legend wowed both paying spectators and pro scouts alike with a .476 batting mark and the tournament lead in base hits with 20. His trio of dramatic gold-medal-game round-trippers still remains an Olympic single-game record (as does his career total of 13 Olympic Games circuit smashes).

The final phase of Omar Linares’s illustrious career was inevitably marred by advancing age, diminishing talent, and a fair share of inevitable injury. And there was also the introduction of wooden bats that did little to enhance his final few domestic and international seasons. A nagging leg injury early in the campaign led to only 25 regular season game appearances during 1998-99, on the eve of the ballyhooed Baltimore Orioles series. One result was the single sub-.300 batting mark of his entire Cuban career (outside of a short 12-game debut as a mere 15-year-old back in 1982-83). A second result of the setback was that Linares sat on the sidelines and began putting on the excessive weight that he would never shed during the remainder of his active career.

Three final seasons brought the challenge of adjustments to the new MLB-style bats, as well as lingering effects from the damaged leg and extra poundage. Nonetheless Linares rebounded with impressive averages of .325, .400 and .398, although none of those campaigns found the Pinar star in good enough physical condition to appear in more than 50 regular season contests, or barely half the regular-season schedule. A final hurrah came in 2001-02 when – now limited to a DH role – the former all-star third sacker led his Pinar club to the league post-season semifinals as the team’s top offensive weapon (batting .386 in regular-season action). Linares’s unparalleled domestic league career fittingly ended in near-storybook fashion when he missed by mere inches of blasting the season’s most significant homer in his final island plate appearance. With Sancti Spíritus and Pinar deadlocked at three games apiece in the post-season semifinals, Linares squared off against the league’s top hurler Maels Rodríguez with the potential winning tallies aboard and two retired in the home ninth. A circus catch above the center field barrier robbed Linares of an historic blow and ended both Pinar’s season and Omar’s own incomparable league sojourn.

Throughout Linares’s active career occasional stories circulated in the North American press about astronomical offers for his services from U.S. and Asian professional teams. Most of these tales were likely apocryphal, though there were certainly big league scouts and club executives privately fantasizing if not publicly putting themselves on record about plans for luring away the prized Cuban star. One rumor (apparently nowhere verified in any press accounts) had the New York Yankees offering the Cuban government $40 million for the services of the star third baseman; another such story involved a $100 million offer by the Toronto Blue Jays on the heels of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics for a package deal including both Linares and home run king Orestes Kindelán. The Toronto overture was said to contain a rumored plan that the two would play only home games in Canada to avoid conflicts with the U.S. Helms-Burton embargo legislation that outlawed monies paid to Cuban citizens. Omar’s wife Dianelys also spoke publicly of a $26 million offer from the Atlanta Braves in the aftermath of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics during her 2000 interview with biographer Juan Martínez.4

One event involving proposals presented to Linares for MLB riches does indeed, however, have some factual basis. The aging Cuban star grabbed the spotlight at Baltimore’s Camden Yards during pregame festivities (preceding the May 1999 Cuba-Orioles rematch) when he first posed for photographers with Cal Ripken Jr. and then fielded questions from a North American press contingent seemingly far more interested in politics and overblown issues of Cuban ballplayer “defections” than with any romance attached to the rare exhibition contest itself. 5 Selected for a pre-game press conference, Linares and teammate Luis Ulacia (then a star outfielder and later a National Series manager with the Camagüey ball club) were peppered with questions about how they might like to play for the “real” major leagues for real dollars. Both politely expressed their desires to join the high-paying pros – as long as they could maintain permanent off-season residence back home in Cuba. Ulacia further remarked that he would play “for free” in the majors since the baseball experience itself was far more vital to him than the money. The remarks seemed carefully crafted to emphasize that it was not necessarily the Cuban government that stood in the way of Cuban stars like themselves joining MLB clubs. The thinly veiled joke of course was that it was U.S. Helms-Burton embargo legislation that prevented salaries paid to Cubans who didn’t agree to “defect” from their homeland; and also of course that the MLB players’ union would never stand for any league player offering his services to American or National League clubs without any lofty salary as compensation.

Omar’s final rankings on all-time lists of Cuban offensive achievement will most certainly eventually slip, as is normally the case with any of baseball’s grandest stars. This is likely to be especially true in Cuba in light of the endless supply of remarkable hitting talent that has already sprung forth in the new millennium. When the Castro government broke with earlier precedent and shipped four top veteran stars (Linares, league career hits leader Antonio Pacheco, home run champion Orestes Kindelán, and shortstop idol Germán Mesa) to Japan in 2002, the move was viewed by most savvy observers of island baseball as a thinly disguised effort to improve a stagnating national team to fresher and more productive young talent6. Pacheco, Mesa and Kindelán were officially loaned to the Japanese Baseball Federation as “coaches” although all three did participate briefly in the Asian country’s high-level industrial league.

But the movement of Linares to the Chunichi Dragons of the Nippon Central League was truly a ground-breaking event in post-revolution Cuban baseball, since it represented the first-ever peddling of a Cuban star to a professional circuit. The Cuban sports ministry had maintained steadfastly over the years Fidel Castro’s high-minded view that non-professional sport was an important reflection of Cuba’s superior system in which athletes played only for local and national sporting pride and not for free-market-induced personal riches. The loaning of Linares to the Chunichi ball club was the first trafficking in more than four decades (if one omits the exhibition series exchange in 1999 with the MLB Baltimore Orioles) between Cuba’s amateur-flavored national sport and the profit-minded professional organizations found in either Asia or North America.

While an eventual three-year sojourn in Japan (2002-2004) did provide some financial rewards for the aging Cuban star, it did little or nothing to sustain a still considerable Linares legend.7 In the end the Japanese League venture was hardly a wise career move since it fueled the frequent charges of doubters outside Cuba who claimed the slugger’s reputed skills were unfairly buoyed by the lower-level amateur circuits in which he long performed. Perhaps suffering from a degree of culture shock after moving from a small-town atmosphere in Pinar del Río to a bustling Asian metropolis in Nagoya, and more even obviously hampered by ballooning weight and nagging effects of his lingering leg injuries, Linares experienced a disastrous Japanese debut: the former Pinar clean-up hitter played sparingly (46 ABs with but 8 hits, 5 RBIs and a single homer) and was used mostly for infrequent pitch-hitting assignments. Despite spending a large slice of his second season with the Dragons’ farm club, Linares tripled his at-bats in 2003 but was only slightly more productive (6 homers and a .229 BA). Sharing time at first base with regular Hiroyuki Watanabe, the still overweight Cuban enjoyed a more productive if only marginally impressive third season (.283 BA and 28 RBI) with Chunichi before retiring from his personally deflating Japanese adventure.

A somewhat negative issue attached to the Linares slugging legacy will always be the fact that the Cuban slugger experienced more than ninety per cent of his career during an era employing aluminum bats. Only his final three domestic seasons were played with wooden weapons, meaning that only 11% of his career hits (241 of 2195), a mere 6% of his homers (25 of 404), and only 9% of his RBIs (115 of 1221) were achieved with the kind of offensive lumber now used by 21st century Cuban League sluggers. The Winnipeg Pan American Games of August 1999 was the landmark event that marked a simultaneous return to traditional wooden bats as well as the initial introduction of high level professional ballplayers on most North American, Asian and Caribbean Basin ball clubs. Of Linares’s 23 major outings on an international stage, only the final trio came in this revamped modern era; in those three final tournament venues his composite average dropped to .277 (compared to a hefty lifetime international BA of .430).

Questions might justifiably be raised about whether such a dip in late-career performance is best explained by normal aging and an inevitable slide after age 35, or the sudden loss of aluminum weapons. It is nonetheless difficult to compare Linares as a slugger with such modern-era 21st-century island greats as Frederich Cepeda (the only unanimous all-star selection at the 2009 MLB World Baseball Classic), Alexei Bell (the first to cross the National Series single-season 30 home run plateau, in 2008), Yulieski Gourriel (present national team third base star seemingly on a rapid course to eventually overhauling most of Linares’s career slugging marks), and Alfredo Despaigne (the current National Series record holder with 32 homers in both 2009 and 2010, and owner of the single-event IBAF World Cup home run standard of 11 in 2009)8. Not only have modern-day Cuban stars used bats equivalent to those employed by big leaguers, but they have for the last ten years been facing top-level pro hurlers in all international tournament venues.

After three mostly disappointing seasons as a journeyman ballplayer in Japan, Omar returned to Cuba in early 2005 to launch a coaching career that would keep him close to the beloved national sport with which his name had become synonymous for nearly a quarter-century. Several brief assignments (in Panama and Nicaragua) on loan from INDER (the Cuban sports ministry) were followed in July 2007 by an initial assignment as bench coach and batting instructor (under manager Victor Mesa) with a level-two Cuban national squad that earned gold medal honors at the Rotterdam (Netherlands) World Port Tournament. Most Dutch fans attending that event failed to recognize Linares on the Cuban bench since the once trim if muscular star had by then ballooned to nearly 300 pounds in girth. A much slimmer Linares joined new manager (and fellow national squad teammate) Germán Mesa on the bench of the popular Havana Industriales Blue Lions squad at the outset of the 2008-09 National Series season. Much more physically fit and apparently buoyed by new enthusiasm, Linares next played a significant role in quickly molding a young Industriales ball club into surprise league champions a mere season later. And the summer of 2010 also saw Linares serving as bench coach (under manager Eduardo Martín) of the equally reenergized Cuban national team that ended a brief international dry spell by ringing up gold medal championships in both the fifth World University Games (Tokyo) and the final edition of the Intercontinental Cup (Taiwan).

The primary legacy of “El Niño” Linares will long remain far more than his sterling and unmatched performances in international venues or his lengthy list of still-standing domestic Cuban League record-book feats. The great Cuban slugger remains both on and off the island nation a perfect “poster boy” for the deep-seated loyalty of the great majority of late-20th-century Cuban diamond stars. The certain recipient of huge financial rewards had he ever opted to abandon the Cuban baseball system which raised him and made possible his early stardom, Linares repeatedly expressed his absolute preference for the love of millions of Cuban fans over the lucre of millions of North American big-league dollars.

Interviewed by Omar’s Spanish-language biographer Juan A. Martínez de Osaba y Goenaga in 1998, Juan Carlos Linares was again presented the question so often raised by so many: “Why didn’t Omar ever want to be a millionaire?” Juan Carlos provides a fitting (if for many hard to accept) response: “Because of the 11 million fans that admired and loved him, and because of our family. The fundamental thing is that the nation loves us, and that is the greatest honor of being a Cuban.”9 Omar himself remained mostly silent about his loyalties to Cuba’s amateur-based national sport. But his bat and his glove were never silent when it came to demonstrating big game after big game the qualities of his unparalleled baseball-playing reputation and dedication. Many consider him the greatest ballplayer ever produced (pre- or post-revolution) by an island nation unsurpassed for baseball fanaticism. There are even those (not a few of them professional big league scouts) who will quietly tell you that in his heyday he may have been just about the best there ever was – period and end of story.

Last revised: July 1, 2016

Statistical Records

It seems important to include a capsule of Omar Linares’s career domestic, international and Japanese professional batting statistics here, since these year-by-year numbers are not found in any single available print or on-line source, either in Cuba or the United States.

Season-by-Season Cuban League Statistics (1982-2002)

Note: Batting records for 1982-83 through 1994-95 include combined statistics from both National Series and Selective Series seasons. Records for 1995-96 and 1996-97 include both National Series and Copa de la Revolution seasons. Cuban statistics also include playoff (post-season) numbers.

National Series and Selective Series Teams: Vegueros (Pinar del Río Province), Pinar del Río and Occidentales. Copa de la Revolution Team: Pinar del Río.

| Year | AVG | G | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | TB | BB/SO | SLG |

| 82-83 | .247 | 27 | 12 | 19 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 24 | 5/17 | .312 |

| 83-84 | .306 | 112 | 86 | 140 | 24 | 3 | 11 | 35 | 203 | 37/55 | .444 |

| 84-85 | .364 | 111 | 96 | 160 | 24 | 11 | 18 | 59 | 260 | 68/57 | .591 |

| 85-86 | .387 | 96 | 84 | 129 | 16 | 3 | 20 | 70 | 211 | 67/39 | .630 |

| 86-87 | .341 | 94 | 88 | 116 | 14 | 2 | 24 | 59 | 206 | 65/48 | .606 |

| 87-88 | .389 | 94 | 101 | 135 | 15 | 4 | 31 | 91 | 251 | 63/33 | .723 |

| 88-89 | .377 | 108 | 106 | 160 | 21 | 2 | 36 | 87 | 293 | 58/35 | .691 |

| 89-90 | .425 | 110 | 109 | 166 | 18 | 3 | 35 | 90 | 295 | 87/46 | .754 |

| 90-91 | .374 | 108 | 109 | 136 | 23 | 3 | 26 | 75 | 243 | 102/44 | .668 |

| 91-92 | .393 | 107 | 109 | 140 | 28 | 1 | 34 | 94 | 272 | 107/36 | .764 |

| 92-93 | .423 | 91 | 91 | 129 | 18 | 5 | 26 | 73 | 235 | 85/31 | .770 |

| 93-94 | .365 | 99 | 93 | 120 | 15 | 7 | 27 | 96 | 230 | 93/29 | .699 |

| 94-95 | .357 | 84 | 93 | 100 | 19 | 0 | 25 | 71 | 194 | 87/33 | .693 |

| 95-96 | .364 | 95 | 98 | 118 | 14 | 3 | 31 | 96 | 231 | 88/44 | .713 |

| 96-97 | .387 | 68 | 69 | 91 | 16 | 2 | 23 | 63 | 180 | 61/21 | .766 |

| 97-98 | .342 | 61 | 46 | 67 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 31 | 108 | 48/18 | .551 |

| 98-99 | .272 | 30 | 21 | 28 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 38 | 28/12 | .369 |

| 99-00 | .325 | 92 | 50 | 99 | 21 | 1 | 8 | 31 | 146 | 75/31 | .479 |

| 00-01 | .400 | 58 | 48 | 76 | 14 | 1 | 9 | 41 | 119 | 70/23 | .626 |

| 01-02 | .398 | 46 | 38 | 66 | 11 | 1 | 8 | 43 | 103 | 33/23 | .620 |

| Totals | .368 | 1691 | 1547 | 2195 | 327 | 54 | 404 | 1221 | 3842 | 1327/675 | .644 |

Cuban League Leader (SS=Selective Series Season): Batting Champion (1985, 1986, 1990, 1992, 1992SS, 1993); Runs (1985, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1991SS, 1992SS, 1993, 1995); Base Hits (1990SS); Triples (1985); Home Runs (1992SS); RBI (1988SS, 1992SS); Walks (1990, 1991SS, 1992, 1992SS, 1993, 1994, 1994SS, 1995, 1996); Intentional Walks (1986, 1990, 1991, 1991SS, 1992, 1992SS, 1993, 1994, 1994SS, 1996); Sacrifice Flies (1994SS)

Cumulative Cuban National Team Statistics (1986-2001)

| Event (# times) | BA | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BB | SO |

| World Cup (6) | .443 | 219 | 97 | 10 | 4 | 22 | 70 | 19 | 27 |

| Olympic Games (3) | .444 | 108 | 48 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 27 | 13 | 20 |

| Pan Am Games (4) | .369 | 111 | 41 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 31 | 29 | 13 |

| Cent. Amer. Gms (4) | .380 | 100 | 38 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 27 | 14 | 15 |

| Intercont. Cup (6) | .464 | 211 | 98 | 20 | 3 | 27 | 72 | 26 | 26 |

| Totals (23) | .430 | 749 | 322 | 50 | 15 | 78 | 227 | 101 | 101 |

International Tournament Appearances: Intercontinental Cup VII (1985 Canada); Central American Games XV (1986 Dominican Republic); World Cup XXIX (1986 Holland); Pan American Games X (1987, Indianapolis, USA); Intercontinental Cup VIII (1987 Havana, Cuba); World Cup XXX (1988 Italy); Intercontinental Cup IX (1989 Puerto Rico); Central American Games XVI (1990 Mexico); World Cup XXXI (1990 Canada); Pan American Games XI (1991 Havana, Cuba); Olympic Games XXV (1992 Barcelona, Spain); Intercontinental Cup XI (1993 Italy); Central American Games XVII (1993 Puerto Rico); World Cup XXXII (1994 Nicaragua); Pan American Games XII (1995 Argentina); Intercontinental Cup XII (1995 Havana, Cuba); Olympic Games XXVI (1996 Atlanta, USA); Intercontinental Cup XIII (1997 Barcelona, Spain); Central American Games XVIII (1998 Venezuela); World Cup XXXIII (1998 Italy); Pan American Games XIII (1999 Canada); Olympic Games XXVII (2000 Sydney, Australia); World Cup XXXIV (2001 Taipei/Taiwan)

Japan (Central League) Professional Statistics (2002-2004)

| Year | Team | AVG | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI |

| 2002 | Chunichi | .174 | 46 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 2003 | Chunichi | .229 | 144 | 19 | 33 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 28 |

| 2004 | Chunichi | .283 | 159 | 19 | 45 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 28 |

| Totals | .246 | 349 | 40 | 86 | 16 | 0 | 11 | 61 |

Photo Credit

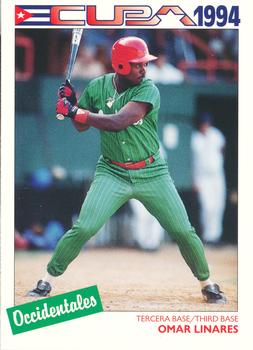

Omar Linares, Trading Card Database.

Sources

Alfonso López, Félix Julio (Editor). Con Las Bases Llenas … Béisbol, Historia y Revolución (With the Bases Loaded … Baseball, History and Revolution). Havana: Editorial Científico-Técnica, 2008.

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007.

Bjarkman, Peter C. “Lifting the Iron Curtain of Cuban Baseball” in: The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History 17 (1997), 31-35.

Jamail, Milton H. Full Count: Inside Cuban Baseball. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000.

Martínez de Osaba y Goenaga, Juan. El Niño Linares (The Kid Linares). Havana, Cuba: Casa Editorial Abril, 2002.10

Padura, Leonardo, and Raúl Arce. Estrellas del Béisbolo: El Alma en el Terreno (Baseball Stars: The Spirit of the Diamond). Havana: Editorial Abril, 1989.

Rucker, Mark, and Peter C. Bjarkman. Smoke: The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball. New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 1999.

“¡Qué clase de niño! Un acercamiento a quien quizás sea el major pelotero en la historia de clásicos nacionales” (“What kind of a kid! An approach to someone who might be the best ballplayer in the history of our national pastime”) Revista Bohemia (November 8, 2010). www.bohemia.cu/2010/11/08/deporte/omar-linares.

2 Juan A. Martínez, El Niño Linares, p. 280. Martínez actually provides these ratios for more offensive categories than those cited in the text here (including triples and extra base hits), and with specific breakdowns for both domestic and international games. His extensive statistical tables and graphs provide additional detailed data on all aspects of Linares’s playing career through the 2000 season.

3 Martínez, El Niño Linares, p. 197. Asked about his greatest single “hit” Linares first responds that it was having three children. Asked to refer specifically to the playing field he then discusses the crucial Pan Am Games homer that washed away his otherwise disastrous Winnipeg performance and guaranteed a chance for Team Cuba to defend its 1996 Atlanta crown at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

4 Martínez, p. 49. When pressed by Martínez to explain why Omar remained in Pinar and in Cuba in the aftermath of the Atlanta offer, Dianelys responded: “I had complete faith that he would return with his gold medal from Atlanta and be content. If he didn’t leave after he had similar offers when he was only 16 and had his whole career ahead of him, there was less chance he would do so now … the reason is the principles of the revolution and the training he received from his parents.” (This author’s translation and paraphrase from the original Spanish.)

5 This author attended the Baltimore pre-game press conference in question (May 3, 1999) and thus heard the remarks by Linares and Ulacia first-hand. While the two Cuban stars were obviously enjoying the opportunity to toy with the U.S. sporting press (providing some silly answers to what they obviously saw as a somewhat silly question), the response was also obviously calculated to defend a Cuban baseball philosophy and undercut MLB’s own big-business orientation. Linares and Ulacia knew what single question would be thrown at them and were well prepared (perhaps even well coached) to provide a most disarming answer.

6 Linares was quickly replaced as national team third sacker by rising Isla de La Juventud (Isle of Youth) star Michel Enríquez, one of the top Cuban hitters of the past decade. Enríquez would soon give way at the hot corner to another young nonpareil, Yunieski Gourriel – although Enríquez has maintained his national team post through 2010 as a designated hitter and now stands as Cuba’s all-time leader in RBI production during international events. Michel Enríquez has also shadowed the most cherished Linares career batting mark (lifetime batting average) during the past decade. At the end of the 2008-09 National Series season they stood in a dead heat at .368, but Enríquez slipped back to third slot in the career standings after an underachieving .315 mark in 2010.

7 It has been popular to emphasize in North American press accounts that Cuban ballplayers – performing under a socialist sporting system – are grossly underpaid, since all receive the same remuneration despite differences in skill level or star status. A standard Cuban ballplayer salary is often reported (without any documentation) as several hundred pesos monthly or only an equivalent of several hundred U.S. dollars annually. Milton Jamail – a respected and careful journalist, reports for example (in his 2000 book, Full Count, p. 68) that Cuban players received “less than $30 (U.S.) a month” a decade ago. The actuality is that current national team stars are paid on a graduated scale, based both on length and quality of service, and now earn as much as $700 U.S. monthly. And there are other perks for top players, such as automobiles, rent-free houses or apartments, and permission to buy luxury items such as computers and televisions while traveling abroad for international competitions. There are, of course, no “official” numbers on ballplayer salaries released from Cuban government sources. And it is indisputable that top Cuba stars don’t earn even a fraction of what they might receive for signing bonuses alone from big league clubs. It is also to be noted that the “sale” of Linares to Japan was of course much more of a revenue-raising source for the government than for Linares himself. While able to accumulate salaries in foreign currency quite superior to anything available at home, Cuban athletes and coaches on loan to other national sports federations (like Cuban doctors or university professors involved in similar exchanges) find 80 percent of their earnings paid directly to the Cuban government, with only about 20 percent going to their own kept salaries.

8 National Series seasons have been 90 games in length since the 1997-98 winter campaign, which explains the reduced quantity of league home run totals. Alfredo Despaigne’s National Series record of 32 (achieved in both 2009 and 2010) would project out to a total of approximately 58 over the course of a full 162 Major League slate of games. With access to MLB-style longer seasons, it is also reasonable to project that Linares’s career total 404 round trippers (as well as the career-record 487 total by Orestes Kindelán) would have soared close to or beyond the 600 mark.

9 The complete Spanish-language Juan Carlos Linares quotation from Juan Martínez’s biography (p. 33-34) is as follows:

Martinez’s question: “¿Por qué Omar nunca ha querido ser millonario?” (How come Omar never wished to be a millionaire?). J.C. Linares’s response: “Por los once millones de cubanos que lo admiran y quieren, y por nuestra familia. Lo fundmental es que el pueblo nos quiera y ese es el major mérito de un cubano. La dignidad, el decoro, que el pueblo nos quiera, nos admire, es el mayor estímulo de un pelotero cubano.” (For the 11 million Cubans that admire and love him, and for our family. The basic thing is that the community loves us and admires us, and that is the best feature of Cubans. Our dignity and pride, and the fact that the people love and admire us, that is the main motivation of a Cuban ballplayer.)

Many skeptics contend that Cuban ballplayers make such altruistic claims about their non-material motivations and their patriotism only out of political pressure and fear of government or community retribution and that such explanation for their motives is never truly sincere. I have personally discussed this issue time and again (in private and “off the record” in Cuba, with numerous national team players who have become trusted friends) and I firmly believe their professions of loyalty to their fans and to their system is indeed quite honest and genuine. Most certainly Cuban ballplayers like all skilled athletes might individually desire a higher level of material reward for their playing skills. Yet the vast majority has remained unwilling to sacrifice higher personal values and patriotic loyalty for the potential (but never certain) riches that might be achieve from the gamble of abandoning family, community and homeland. Their responses are no more “mere lip service” to some ingrained doctrine than are the standard professions by most Americans that they love their own homeland simply because of its idealized “democracy, liberty and personal freedoms.” This is an important point to emphasize here, since so much of the ink about Omar Linares in the North American press has been centered on the questions about his personal decision to play out his entire career under the non-commercial Cuban baseball system.

10 Juan Martínez’s Havana-published Linares biography was released in 2002 (the year of Linares’s departure for Japan) but completed two years earlier. It therefore does not treat “El Niño’s” career after the 2000 National Series season and 2000 Sydney Olympics. It is also (like a number of other similar ballplayer biographies published in Cuba in recent years) far more of a laudatory tribute (filled in large part with quoted testimonials) rather than anything approaching a critical or detailed biographical portrait.

Full Name

Omar Linares Izquierdo Linares

Born

October 23, 1967 at San Juan y Martínez, (CU)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.