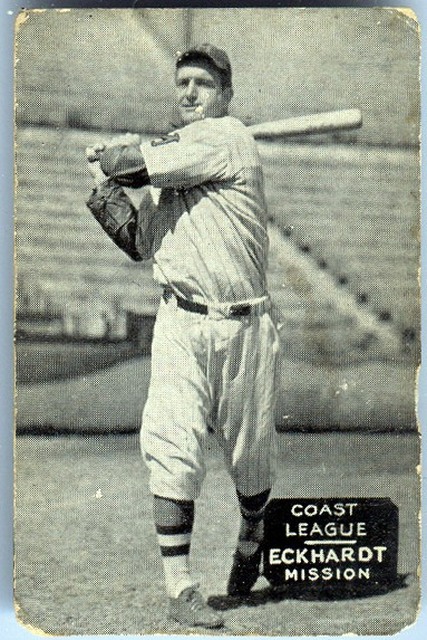

Ox Eckhardt

Ox Eckhardt has the highest lifetime average in the minor leagues of batters with over 1,000 games played. Some sources even suggest that his career batting average was the best of all time.1 A left-handed hitter with an extremely open stance, he was “almost in motion toward first when he hit the ball. Result, a lot of nasty, curving short line drives into left field for singles and doubles.”2 Veteran Gabby Street managed Eckhardt during his heyday with the San Francisco Missions in the Pacific Coast League. He was asked if he would change Eckhardt’s unorthodox style if given the opportunity. Street shot back, “Change a .414 hitter? Are you crazy, or do you think I am? The man can hit standing on his head for all I care. I won’t even talk to him about style.”3

Ox Eckhardt has the highest lifetime average in the minor leagues of batters with over 1,000 games played. Some sources even suggest that his career batting average was the best of all time.1 A left-handed hitter with an extremely open stance, he was “almost in motion toward first when he hit the ball. Result, a lot of nasty, curving short line drives into left field for singles and doubles.”2 Veteran Gabby Street managed Eckhardt during his heyday with the San Francisco Missions in the Pacific Coast League. He was asked if he would change Eckhardt’s unorthodox style if given the opportunity. Street shot back, “Change a .414 hitter? Are you crazy, or do you think I am? The man can hit standing on his head for all I care. I won’t even talk to him about style.”3

Yorktown, Texas, lies in De Witt County, about 45 to 50 miles from the Gulf of Mexico in southeastern Texas. In the 1840s and 1850s there was a large influx of German immigrants to the area. The Eckhardt family immigrated to the county in the late 1870s shortly after the birth of Oscar Gustav Eckhardt in Prussia. He grew up in the county and took Lila Taylor Wimbush as his bride. Their first child, Oscar George, was born on December 23, 1901. James and Virginia later joined the family.

The elder Eckhardt was a pharmacist and moved the family north to Austin, Texas, where he opened a drugstore. The children all attended the local schools. In high school, Oscar was known as Os. The nickname of Ox did not start until he was in professional baseball.4 After graduating from Austin High School, Eckhardt enrolled at the University of Texas in Austin. He had quite a reputation as a football player and had played baseball on the sandlots his whole childhood.

Eckhardt played for the Texas Longhorns in the Thanksgiving Day football game in 1919 as a late replacement. The Austin High School Alumni Association lists his graduation in 1920. Exactly how he played collegiately in 1919 is a mystery. During the 1920 football season he played for the “Shorthorns,” aka “The Ineligibles.” This squad played smaller colleges like San Marcos Teachers College and local high schools.5 It was made up of freshmen and academic ineligibles. Eckhardt also played freshman basketball that winter, although he had not played the sport previously.

In 1921, the football Longhorns opened with St. Edward’s College and drubbed them 33-0. A three-team platoon system was used and Eckhardt saw action with one of the platoons. That was the only football he played in 1921. Articles in the student newspaper mention him as a running back, but no mention of game action is available.6 During the 1922-23 and 1923-24 school years, he was a four-sport participant. His major sports were football and baseball. He was a substitute in basketball and threw the shot-put for the track team when it did not interfere with baseball.

The Texas Longhorns were a football powerhouse in 1922 and 1923. They had a combined record of 15-2-1 and won the Southwest Conference title in 1923. Versatile players were required on the gridiron in those days. Men who could run, pass, and kick were prized as triple threats. Eckhardt played halfback and quarterback and was often the leading rusher. He split kicking duties, doing most of the punting, but was used sparingly as a placekicker. He also played splendid defense and was a punt returner. Eckhardt stood 6-feet-1-inch tall. Over the course of his collegiate and professional career, he was listed at between 175 and 190 pounds, making him as big as many of the linemen he went up against in college.

During the championship 1923 season, Eckhardt scored the first touchdown of the season with a 30-yard run. He gained headlines when he ran amok over Tulane in a 33-0 win and then helped defeat Vanderbilt 16-0 with his strong punting and opportunistic interception on defense. His offensive exploits were such that Baylor designed its game plan to stop him. The Bears stymied Eckhardt by sending defenders from all angles to disrupt his timing. They held the Longhorns to a 7-7 tie; it was the only blemish on an 8-0-1 season for Texas. Despite that one low-key performance, it was noted in the Dallas papers that “of all the backfield men that Texas ever had, none ever surpassed Eckhardt as a charging runner, a passer and a punter.”7 He was named an honorable mention on the Walter Camp All-American team that fall.

In 1928, Eckhardt played professionally for the New York Giants. In 11 games, he scored two touchdowns and kicked an extra point. His 13 points placed him second on the team behind Hinkey Haines in scoring. With an offense that generated only 79 points, it was not surprising that the Giants finished the season 4-7-2.

On the baseball diamond, Eckhardt was a right-handed semipro pitcher with a decent fastball and a good curve. He played summer baseball, but did not try out for the college team until 1922. Practices began in January and the collegiate players were joined by Texas alumnus Bibb Falk and five other major leaguers. Eckhardt’s debut came on March 31, 1922, against Howard Payne College. He pitched four innings of relief in the 11-1 win and struck out five. His coach was William J. Disch, known as Uncle Billy. Disch had a career record of 513-180 at Texas and led its teams to 20 Southwest Conference championships.

Eckhardt earned his first starting assignment on April 10 versus the Arkansas Razorbacks. He pitched seven innings and gave up five runs in the 13-10 Texas win. At the plate, he was 2-for-3. The Longhorns went on to claim the league crown and all the players received gold fountain pens and golden baseballs for their efforts.

Coach Disch increased Eckhardt’s playing time in 1923. When he was not on the mound, he patrolled left field and batted either second or fourth. The Steers also featured Rube Leissner as captain and Horace Kibbie at shortstop. Leissner had a brief minor-league career and Kibbie reached the majors long before Eckhardt, but lasted only part of a season.

Texas got off to a good start in 1923, but was forced to pitch Leissner and Eckhardt almost every game. The wear became obvious when the champion Baylor Bears took the last series to clinch the title. In his professional career, Eckhardt was known for a batting style in which he rarely pulled the ball. This does not appear to be his style in college, where he launched home runs and was described as driving the ball to the outfield. He was also described as “speedy” and said to “field well” while in college.8 In the pros his glovework was a constant source of concern.

In the summer of 1923, Eckhardt joined Leissner, Kibbie, and four other teammates on an independent team in Farmersville, Louisiana. The team posted a 33-15 mark before disbanding in early August. One of its opponents in the league was Bastrop, Louisiana, which featured Joe Jackson in the outfield.9 Shoeless Joe played as Joe Johnson until a series of mid-July newspaper articles outed him. The Bastrop players moved to Americus, Georgia, and entered a South Georgia outlaw league when some of the Louisiana teams refused to play Bastrop and the ineligible Jackson.

The 1924 Longhorns were determined to rebound and reclaim the title. They put together the greatest season in Coach Disch’s career. Their 28-1 record was blemished by a loss to Baylor. Eckhardt had a magnificent season, starting with a pitching win over the visiting Minnesota Gophers. On April 12, he hurled the Steers to an 18-1 win over Texas A&M. He allowed only four hits and struck out 10. At the plate, he launched five singles and a double, stole a base, and scored four times. In mid-May he lashed three homers in a series against Oklahoma A&M. He closed out the season by defeating his nemesis from Baylor, pitcher Jake Freeze, whom he had never bested. Freeze had beaten Eckhardt earlier in the year in the Longhorns’ only loss.

Over the winter of 1923-24, Eckhardt was a member of the Texas basketball squad. Injuries mounted for the team in January and he was likely to be made the starting center until he was confined to bed rest because of a case of the mumps. His coach was Doc Stewart, who would also coach the 1924 football team. Stewart was certain that the basketball experience would help Eckhardt on the gridiron. “He was never able to master a cutback as he should. He preferred to run past or to stiff-arm a would-be tackler,” Stewart said. “By playing basketball Eckhardt has learned how to stop quickly, start quickly, and change direction.”10

In May 1924 as the baseball season wound down, Eckhardt was ruled ineligible for football. It was hoped that the brief appearance he made in 1922 versus St. Edward’s would not count as a season because at the time St. Edward’s was more of a prep school/high school than a college. The faculty review board rejected the notion and chose to end Eckhardt’s eligibility.

In the fall, Eckhardt played with several all-star football teams. He was supposed to play against a team featuring Jim Thorpe, but opted not to participate. In January 1925, he was named an assistant coach at West Texas State Teachers College in Canyon, Texas. He was also appointed an assistant professor of education. In 1925, he became head football coach. He remained with the college until June 1927.

The move to Canyon was very important in Eckhardt’s life. He met Edith Harrison there and the couple wed in 1926.11 Edith was a popular and attractive woman with a sharp sense of humor. The couple never had any children. Eckhardt purchased a cattle ranch outside Austin which would serve as a home base for the couple.12

Eckhardt got his first taste of professional ball in 1925. He was signed by the Austin Senators of the Class D Texas Association. This was a six-team league that also included Corsicana, Mexia, Palestine, Temple, and Terrell. Eckhardt debuted on May 15 against Corsicana playing center field. He also played the next day against the same squad. The teams split the games, each with a 6-3 score. Eckhardt went 2-for-7 with a run scored. In the field, he handled only two fly balls. He was released a short time later.

Eckhardt was playing semipro baseball when Cleveland scout Cy Slapnicka signed him for a tryout with Cleveland. He was to meet the team in Chicago and spend two weeks showing manager Tris Speaker what he could do. At the end of the time he could be farmed out or released.13 The Tribe did not reserve him and he returned to his duties at West Texas. In the spring of 1926, Eckhardt added head baseball coach to his duties.

In 1928, Eckhardt tried professional baseball again when he signed with Amarillo in the Class A Western League. He was involved in a season-long battle for the batting title with Joe Munson of Tulsa and Lee Riley of Pueblo. Munson won the crown with a .385 average and 39 home runs. Eckhardt was listed in news reports with a .380 average.14 His batting prowess created a bit of a bidding war. In late August, he signed with Seattle of the Pacific Coast League but a week later, at the insistence of scout Eddie Goostree, his rights were transferred to the Detroit Tigers.

After a quick look in 1929 spring training, the Tigers optioned Eckhardt to Seattle. In exhibitions and early in the season he split time in center field despite being a “poor fielder.”15 Eckhardt’s bat quickly put an end to the platoon with Andy Anderson. Anderson kept the center-field job and Eckhardt was positioned in left. He raised his average from .333 to .390 in mid-April and led the Indians hitters most of the season. He closed out the campaign at a team-best .354, but that was well off the .407 of Ike Boone with the Missions. In the offseason, Eckhardt took the head football position at El Paso High School.

The Tigers sold Eckhardt’s rights to Seattle after the season. Then Seattle sold his contract to Beaumont in the Class A Texas League. The Exporters finished well off the pace in the 1930 pennant race, but Eckhardt led the league with a .379 batting average. He fully developed his wide-open, left-handed batting stance and led the league with 55 doubles. The Houston Buffalos created a shift when they faced him. The third baseman played behind the bag, the shortstop positioned himself in short left about 20 feet from the foul line, and the second baseman took up the shortstop position. Judging from box scores, the strategy was successful except on July 8, when Eckhardt burned the Buffalos with two triples.

Eckhardt earned a trip to 1931 spring training in Sacramento with Detroit, but found himself back on the Pacific Coast with the San Francisco Missions for the season. The Missions barely escaped the cellar, but Eckhardt led the league with 275 hits and a .369 average. In September, the Boston Braves purchased his rights. He went to 1932 spring training with the Braves and was kept on the roster by manager Bill McKechnie when the team went north. He made his major-league debut on April 16 when he struck out in a pinch-hit appearance against the Giants at the Polo Grounds.

Eckhardt made seven more pinch-hit appearances through May 8 before being returned to the Missions. Overall, he went 2-for-8 with a run scored and one batted in. His 1932 season on the coast was very similar to the previous one. He led the league in batting at .371, but the Missions finished in last place. He returned to the Missions in 1933 and became one of the two big stories of the season. Youthful Joe DiMaggio went on a 61-game hitting streak. Despite the streak, DiMaggio batted a mere .340, far behind the .414 average Eckhardt generated on 315 hits. The batting average stands as the all-time PCL record. His hit total was 10 behind the record set by Paul Strand in 1923.

The 1934 season proved to be a departure from the previous years. The Missions won 101 games but Eckhardt did not win the batting title. That went to Frank Demaree of Los Angeles, who won the Triple Crown with .383/45/173. Eckhardt batted .378 for the second-place Missions. The following season the Missions returned to the second division, but Eckhardt took the batting title again. This time he had to edge out DiMaggio, .399 to .398. Two bunt hits on the final day gave Eckhardt the edge. He earned a return to the majors when his contract was purchased by Casey Stengel’s Dodgers for 1936.

The Dodgers brought in Eckhardt (age 34) and Johnny Cooney (35) to compete for time in the outfield. The season opened with Eckhardt leading off and playing right field; Cooney patrolled center field. Because of Eckhardt’s defensive issues, Stengel sent him to the bench after three games when he was hitting .154. It was obvious that Eckhardt would have to hit over .300 to stay in the lineup. After a stint as a pinch-hitter and pinch-runner, Eckhardt got a second chance and started seven games.

Because the National League’s pitchers and fielders had figured out how to play Eckhardt’s opposite-field hitting, Stengel hoped to convert him to a pull hitter. Eckhardt may have tried to oblige because in the first game back he hit a home run against the Giants. He batted 6-for-28 (.214) in his second audition and was relegated to the bench before his return to the minors in mid-May, to the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association. He hit .353 with Indianapolis, which made the playoffs and eventually lost to Milwaukee in the finals.

Age started to show. Now 36, Eckhardt hit .341 in 1937 with Indianapolis. Defenses were catching up to him and he tried to pull the ball more. The result was seven home runs, but only 20 doubles. The Indians finished in the second division. In 1938, Eckhardt’s contract was moved to the Toledo Mud Hens, also in the American Association. He batted cleanup and in the second game of the season hit a double and a triple. He also muffed a flyball and then made a throwing error allowing Milwaukee to walk away with the win. He fell into the worst slump of his career and was released with a .229 batting average after 55 games.

The San Antonio Missions (some papers called them the Padres) of the Texas League purchased Eckhardt’s contract on June 26. The Missions had a team batting average below .250 and hoped that the veteran could regain his stroke.16 His batting eye slowly responded and by mid-August he had taken over the league lead with a .340 batting average. Two weeks later Eckhardt was at .376 and closed out the campaign at .387. His hitting revived the Missions, who finished second. They swept Oklahoma City in the first round of playoffs, but lost the finals to Beaumont.

In January, the Memphis Chicks of the Southern Association purchased Eckhardt’s contract. He initially balked at the assignment, wanting to stay in the Texas League, close to home. He relented and joined Memphis. He hit .361, barely losing the batting title to Bert Haas, who hit .365. The Chicks made the playoffs but were swept in the first round by Nashville, which went on to win the title from Atlanta. Eckhardt closed out his playing days the following year, 1940, with the Dallas Steers of the Texas League. Dallas finished in the second division and Eckhardt posted a .293 average at the age of 39.

Eckhardt left baseball behind and turned his attentions to Edith and the cattle business. In the late 1940s he moved back to Yorktown, Texas, but stayed in the livestock trade. Eckhardt was at home when he died after a major heart attack on April 22, 1951. He was buried in the Oakwood Cemetery in Austin, Texas.

Acknolwedgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Baseball-Reference was used extensively, but it must be noted that (as of May 20, 2017) B-R lists Eckhardt with Beaumont in 1938 and not San Antonio. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff’s Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, first edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997) was also consulted frequently.

Notes

1 Scott Ferkovich, “The Ox That Ate the Georgia Peach,” seamheads.com/blog/2014/08/03/the-ox-that-ate-the-georgia-peach/ .

2 L.H.Gregory, “Greg’s Gossip,” Oregonian (Portland), August 30, 1951: 25.

3 Ibid.

4 “Ox for Casey’s Cart,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1935: 1. A search of TSN revealed this article as the first use of “Ox” as his nickname in the national paper. The West Coast papers used it earlier in the 1935 season, first calling him “The Ox” and then shortening it to simply “Ox.”

5 “Shorthorns Down Teachers 69-0 on Slow Gridiron,” Daily Texan, (Austin, campus newspaper), October 24, 1920: 1.

6 “Texas Men Who Face Vanderbilt at Dallas Saturday,” Daily Texan, October 19, 1921: 3.

7 “Longhorns Lose Many 1923 Players for Next Year,” Dallas Morning News, November 25, 1923: 4.

8 Daily Texan, May 12, 1923: 2.

9 “Dallas Boys Star on Louisiana Nine,” Dallas Morning News, July 15, 1923: 3.

10 “Cage Practice Aids Eckhardt as Grid Star,” Houston Post, February 12, 1924: 10.

11 The 1930 census lists them as having been married four years, hence the use of 1926. No marriage certificate has been located by the author to confirm the date.

12 The Sporting News, May 2, 1951: 33.

13 “Os Eckhardt to Cleveland,” Dallas Morning News, June 23, 1925: 10.

14 “Former Dallas Player Again Tops Western League Hitters,” Dallas Morning News, September 9, 1928: 3.

15 Alex Shults, “Baseball Will Make Its Bow Here Tuesday,” Seattle Daily Times, April7, 1929: 21.

16 “Missions Land Os Eckhardt,” Dallas Morning News, June 27, 1938: 3.

Full Name

Oscar George Eckhardt

Born

December 23, 1901 at Yorktown, TX (USA)

Died

April 22, 1951 at Yorktown, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.