Pat Flaherty

His name was Edmund Joseph Flaherty. People called him Ed, Eddie, and Pat. He was a pitcher who became a spring training prospect with the Washington Senators and Boston Red Sox, but he never played in a major-league regular season game. He received a World Series medal with the New York Giants, though he spent the entire Series in the bullpen. His name isn’t in any baseball encyclopedia, but his life is indeed worth remembering. Ironically, through his career outside of baseball Flaherty was seen by more people than were most of his contemporaries who weren’t named Cobb or Ruth.

Born March 8, 1897, in Washington, D.C., Flaherty attended Eastern High School for a couple of years, and finished that academic level by prepping at the Dean Academy in Franklin, Massachusetts. He played baseball and football, boxed, and wrestled. He was gaining attention from the Washington sports reporters before he graduated from high school.

He made connections all his life. While in high school, he became a page to House Speaker James Beauchamp “Champ” Clark. Through that contact, he was assured an appointment to West Point. But he never went to college. He was too busy taking on jobs in sports and in the military.

Pat’s uncle was Patrick Henry Flaherty, a major-league third baseman with the 1894 Louisville team in the National League. Pat’s father Mike was a friend of Clark Griffith, who signed the lad in 1916 while he was still a teenager. Pat’s best pitch was reputed to be a spitball, which was legal at that time.

Pat first arrived at the Senators spring training camp in Augusta, Georgia, on February 28, 1917, at the age of 19. It had already been decided that he would be farmed out to the Des Moines Boosters in the Class-A Western League as final payment in a swap for Nats hurler Claude Thomas. But Griffith wanted Pat to get a workout with the big leaguers while awaiting final instructions from Des Moines. On March 12, Pat made his first appearance in an inter-squad game. He gave up only one run in four innings and hit a long single that turned into an out as he tried to stretch it into a double. He hurled again on March 14, yielding four runs in one inning and holding the opposition scoreless in the following three frames. Pat continued to pitch in Senators inter-squad games until March 30, when he was shipped out.

In 1918, Pat was missing from spring training because he was a World War I pilot with the U.S. Army Aviation Corps in Memphis, Tennessee. In the latter half of 1917, he had attended the School of Military Aeronautics at Princeton University. He graduated from there on January 26, 1918.

Flaherty reappeared at a Nats training camp in Augusta, Georgia, on March 16, 1919. He changed his motion from overhead to sidearm. His control began to improve, but he was inconsistent. In a game on March 30, he was rocked by opposing batters and gave up a home run to Walter Johnson. He asked his manager for permission to pitch again two days later and came back with four scoreless innings. Returning to the mound on April 3, he yielded only one run in four innings, despite his fielders’ committing six errors behind him. The (Washington DC) Evening Star reporter opined that no runners would have reached second base if it had not been for the sloppy fielding of Flaherty’s teammates. On April 5, Flaherty pitched four scoreless innings, but evinced some control problems again. On April 7, he started complaining about a sore arm. On the morning of April 10, he participated in his final workout with the Senators. He rejected their offer to go to a minor-league team, and headed home.

Flaherty spent the rest of 1919 with the Baltimore Dry Docks semipro team, where he chalked up a 31-7 record. The Dry Docks played in the Delaware Shipyard League and won the championship that year. The Dry Docks had high-caliber talent, with future Hall-of-Famer Waite Hoyt being their other main starter for the first part of the season. Hoyt had performed so well in an exhibition game against the Cincinnati Reds that he had been subsequently signed to a Boston Red Sox contract. Former big-leaguers Dave Danforth, Hugh Canavan, Eddie Zimmerman, and Johnny Bates were also on the Dry Docks’ staff.

During the 1919 season, the Dry Docks played exhibition games against the Red Sox, Braves, and Reds, and encountered a rainout for a game scheduled with the Phillies. In the September 7 game against the Red Sox, 10,000 Baltimore fans filled Orioles Park to witness the return of Babe Ruth to his hometown. The Babe did not disappoint, as he slugged two homers off Pat Flaherty and also pitched for the final two innings. Although Flaherty and the Dry Docks lost 10-6, Pat pitched a complete game. The Baltimore Sun reported that he only suffered two bad innings and was not roughed up during the rest of the game.

After the 1919 season ended, the International League champion Baltimore Orioles entered into a seven-game series with the Dry Docks for the honor of being Baltimore’s best team. The Dry Docks won the series, four games to three. Flaherty won one game and lost one. His most memorable game during this series came on September 21. He threw a pitch close to the head of Oriole (and former major leaguer) Merwin Jacobson. The two then rushed towards each other and threw a few punches. Other players and some members of the crowd came into the fracas. It ended with the police seizing both players, and hauling them to the Northern Police Station, where they were charged with “acting in a disorderly manner in a public resort.” The two players were back playing ball against each other the next day.

Flaherty spent the 1920 spring training season with the Boston Red Sox. On March 18, he earned a win over the Pittsburgh Pirates, despite giving up two runs in three innings. On March 29, he pitched against the New York Giants and yielded six hits and six runs in five innings. The Red Sox kept him on into the beginning of the season, mostly as a batting practice pitcher. On April 17, they traded him to the San Francisco Seals for former major-leaguer Herb Hunter, who would get another crack at the big leagues for a few games with the Red Sox. Flaherty subsequently moved on from San Francisco to Akron.

In 1920, Flaherty pitched for the Akron Buckeyes in the International League. Jim Thorpe was one of his teammates and made a lasting impression on him. Flaherty had a 12-5 record with a 3.35 ERA for the Buckeyes. Thorpe hit .360 in 128 games. This was the season after Thorpe’s major-league career had ended, but he still had his batting skills.

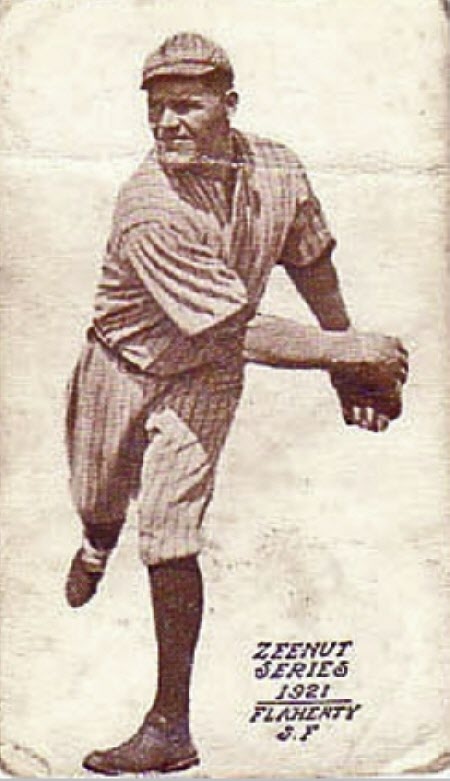

Flaherty began 1921 pitching for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. This stint brought him his only baseball card, a 1921 Zeenuts issue. He moved on to the Shreveport Gassers in the Texas League before the New York Giants announced on September 12 that Pat Flaherty was being promoted to their team. In 1921, the World Series had the potential to run nine games, so it appears that the Giants were stocking additional pitching help for an emergency. The Giants beat the Yankees in eight games, and Flaherty got to watch the proceedings from the bullpen.

Flaherty did rise to the major league level in football. He was an end and halfback, and a fine punter. He played at the opposite end of the line from George Halas with the 1923 Chicago Bears. The Washington Post of December 24, 1923, carried an article entitled “Flaherty Back Home After Great Season.” The article said: “Patsy Flaherty, last year’s star end for the Washington professional football team, has just returned to town after a successful season with the Chicago Bears, runners-up in the national pro race and winners of the 1923 Western professional title. Flaherty participated in twelve of the thirteen games, which the Bears played and made quite a name for himself in the Windy City as a punter. He started the season at end but, because of his passing and booting ability, was shifted to the back field where he starred.” He also played for the Bears in 1924.

Flaherty played in one game in 1926 with the Brooklyn Horsemen of the old American Football League. Red Grange had been blocked from starting an NFL team in the New York area, so he formed the AFL instead. Quarterback Harry Stuhldreher, one of the Four Horsemen of Notre Dame, led the Horsemen. On November 7, in a game against Red Grange’s team, Flaherty played and scored a touchdown by grabbing a deflected pass and scampering 35 yards down the field. The Horsemen franchise only played four games before they were merged into the Brooklyn Lions. Boxing promoter Humbert Fugazy was the owner of the Horsemen. In 1929, Pat Flaherty would marry Fugazy’s daughter, Dorothea. She too was an athlete, having qualified for the Olympics in swimming.

Flaherty also played pro football with the New York Giants. A Charlottesville, Virginia, newspaper article places him with the football Giants in the era of Bruce Caldwell, Jack McBride and Hinkey Haines, the latter a fellow who also played briefly in the majors with the Yankees. Since Caldwell’s first year with the Giants and Haines’ last year were the same, 1928, the Flaherty who appeared with the Giants at left end in a September 30 game that year was Pat.

Along with the above experience in pro football, Flaherty also played for several Washington, D.C., independent teams for a number of seasons.

He was in the military service during the Mexican border war, World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, having attained the rank of major by the time of his final discharge. After his professional athletic career ended, he went into the music publishing business with the DeSylva-Brown firm of New York. And after that, he became a Hollywood actor, with around 250 films to his credit. He was in many of the baseball classics and other recognizable movies.

He was first drawn to California because his brother, Vincent X. Flaherty, had preceded him there. Through his brother’s connections, he landed a job working as a producer for Joseph Kennedy in 1930. As the Great Depression took hold, he lost the job as a producer and turned to acting.

He played Red Sox manager Bill Carrigan in The Babe Ruth Story. He was umpire Bill Klem in The Winning Team. He taught Gary Cooper to pitch and appeared with him in Meet John Doe. Pat and his good friend Lefty O’Doul worked on Cooper’s baseball skills for the latter’s role as Lou Gehrig in Pride of the Yankees. Pat had a small acting part in that movie as well. He was in The Jackie Robinson Story. He was the Braves manager in Angels in the Outfield. He played in The Stratton Story, Death on the Diamond, It Happened in Flatbush, and Take Me Out to the Ball Game.

Flaherty had first befriended Jim Thorpe when the two were playing baseball. He campaigned to have Thorpe’s Olympic medals restored and developed the initial writing for what later became a movie, Jim Thorpe-All-American. Pat turned his work over to his brother, Vincent X. Flaherty, who became a screenwriter for the movie. Vince was also a screenwriter for the movie PT 109, about John F. Kennedy. Earlier in his career, Vince was a sportswriter for the Washington Times-Herald.

Flaherty was in some of the top all-time films. The following three of his movies won Academy Awards for Best Picture of the Year: Mutiny on the Bounty (he was the lead mutineer), You Can‘t Take It With You, and The Best Years of Our Lives. The following films in which he appeared won nominations for Best Picture or Outstanding Motion Picture: Sergeant York, The Grapes of Wrath, The Treasure of The Sierra Madre, Yankee Doodle Dandy, and Naughty Marietta. My Man Godfrey was the first movie to receive Oscar nominations in all four acting categories (Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor, Best Supporting Actress).He became friends with Ronald Reagan when the two worked together on Knute Rockne All American, the movie remembered for the “Win One for the Gipper” speech. Flaherty appeared in other classic films: A Day at the Races, Boom Town, Dodge City, Key Largo, The Lemon Drop Kid, Gentleman Jim [Corbett], and The Asphalt Jungle. He was also in popular film series like Blondie, the Bowery Boys, the Thin Man, and Charlie Chan.

Moreover, he appeared with the Marx Brothers, Charlie Chaplin, Bob Hope, Red Skelton, Joe E. Brown, and the adorable young Shirley Temple. He was with heartthrobs Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, Cary Grant, and Frank Sinatra. There were the famous pairs Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn, Nelson Eddy and Jeannette MacDonald, William Powell and Myrna Loy, not to mention Bud Abbott and Lou Costello. Finally, there were beauties like Esther Williams, Doris Day, Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable, Jean Harlow, Janet Leigh, Debbie Reynolds, and Jane Powell.

Starring roles weren’t in the cards for him. One of his highlights was having 10 or so lines in Meet John Doe with Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck. He appeared without credit in many movies, and even his credited roles tended to be relatively brief. He accepted it all with good humor. An article by Bob Ray in the September 8, 1940, issue of the Los Angeles Times quoted him as follows: “Strangely, in about nine out of ten parts that come my way, the script always calls for me to be knocked down. And I’ve compiled a pretty good list of screen celebrities who’ve either won decisions over me or kayoed me. Among them are Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, Jimmy Cagney, Melvyn Douglas, Brian Aherne, Dick Arlen, Andy Devine, Jack Holt, Big Boy Williams, Wayne Morris and—don’t laugh—Jane Withers.” Having been a competitive boxer and wrestler in his youth, it must have been difficult for Flaherty to become a fall guy, but he was very adaptable as a Hollywood actor.

As Hollywood moved into the 1950s, television began to take hold in American households. It became more difficult to make a living as a film actor, so Flaherty moved on to become a public relations specialist with Sperry-Piedmont, an affiliate of the Sperry Rand Corporation. He did make a few television appearances, but his acting career was essentially completed.

Flaherty was married twice. His first wife was the former Dorothy Fiske. From census data, it is estimated that the marriage took place around 1919. The couple had one child: Edmund Flaherty Jr. was born in 1919 and died in 1995, by which time his name had been changed to Edmund Graham. The first marriage ended in divorce during the 1920’s. At the time of the 1930 census, Dorothy Fiske had re-married and was living as Dorothy Graham in the Bronx, New York, with her son Edmund Jr. and some additional children. Pat had married Dorothea Fugazy, the daughter of New York boxing promoter Humbert Fugazy, on January 19, 1929. Fugazy had grand visions of using outdoor venues to draw larger fight crowds. He was the first promoter to gain the exclusive right to use the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field for boxing matches. Indeed, Fugazy promoted two of Jim Braddock’s fights — against Norman “Doc” Conrad in Jersey City on December 26, 1926, and against Joe Sekyra in Ebbets Field on August 8, 1928. Considering some of the people who decked Pat in the movies, it’s clear that the script didn’t allow Pat to follow his father-in-law’s advice! Dorothea and Pat had two children — Patrick Joseph Flaherty and Frances X. Flaherty Knox.

He died on December 4, 1970, in New York City. He was a man of many talents who knew how to live life to the fullest by making many friends. The list of celebrities who considered him a friend is enormous. As just one example, when it came time for his daughter Frances to learn to play golf, it was his friend Smoky Joe Wood who taught her. His Washington Senators teammates enjoyed having him around in spring training, and they missed him when he was shipped out. It was the Senators fans’ loss that they were never able to see him pitch for the team during the regular season.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Edmond “Pat” Flaherty’s daughter, Frances Flaherty Knox, generously provided a great deal of information for this article. Other sources not already cited above include many issues of the Washington Star, Washington Post, Baltimore Sun, and New York Times. During the week of November 5, 1951, Dan Parker wrote a column about the athletic Flaherty family for the New York Daily Mirror. On January 9, 1957, Bob Addie published a column about the Flaherty men in the Washington Post and Times Herald.

The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, by Lloyd Johnson; The International League, by Marshall Wright; and Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia, by the editors of Total Baseball, were used as references. Two other helpful sources were the Internet Movie Data Base (IMDb) website, and email correspondence with Bob Carroll of the Professional Football Researchers Association. Rob Edelman, a SABR expert on baseball’s connection to the movies, also kindly corresponded with me on this subject. SABR member Tom McElroy contributed the research on the Baltimore Dry Docks exhibition game against the Boston Red Sox.

Additional Information

Pat Flaherty was in films with almost every Hollywood legend of his day: Jimmy Stewart, Loretta Young, Elsa Lanchester, Kirk Douglas, John Wayne, Judy Garland, Burt Lancaster, Ginger Rogers, Henry Fonda, Rosalind Russell, Lionel Barrymore, John Barrymore, Claire Trevor, Edward G. Robinson, Jane Wyman, Rita Hayworth, Olivia de Havilland, Carole Lombard, Barbara Stanwyck, Anne Sheridan, Jean Arthur, Charles Laughton, Irene Dunne, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., William Holden, and many others. Jazz fans found him in New Orleans, along with Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, and Woody Herman.

Full Name

Edmund Joseph Flaherty

Born

March 8, 1897 at Washignton, DC (US)

Died

December 4, 1970 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.